Planetary Radio • Dec 19, 2025

Book Club Edition: MOONS: The Mysteries and Marvels of our Solar System by Kate Howells

On This Episode

Kate Howells

Public Education Specialist for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

It was such a delight to feature work by our own Kate Howells in The Planetary Society’s member book club. We keep Kate busy as our public education specialist, but she found time to write about many of her favorite natural satellites in this richly illustrated edition. Join her and book club host Mat Kaplan for a journey taking us from our own Moon, past Europa, Titan, and many more, and out across a galaxy that is no doubt full of worlds circling other worlds.

Planetary Society Book Club Livestream: MOONS by Kate Howells The full title of our October 2025 selection is Moons: The Mysteries and Marvels of our Solar System. They really are! The Planetary Society's public education specialist has created a richly-illustrated introduction to the amazingly diverse moons of our solar system, from distant Charon to our own Moon/Luna. She saves a few pages for consideration of the billions of moons that are surely circling other planets across the Milky Way galaxy. Kate joins Mat Kaplan for a happy romp among these small worlds.

Related Links

- Moons by Kate Howells | Hardie Grant Publishing

- The Moon, gateway for science and exploration

- Your Guide to Water on the Moon

- Can the Moon be upside down?

- Is the Moon shrinking?

- Why send people back to the Moon?

- The two-faced Moon

- What are Jupiter's Galilean moons?

- Io, Jupiter’s chaotic volcano moon

- Europa Clipper, a mission to Jupiter's icy moon

- Europa, Jupiter's possible watery moon

- Enceladus, Saturn's moon with a hidden ocean

- China eyes Saturn's icy moon Enceladus in the hunt for habitability

- When will we explore Enceladus to find alien life?

- Water plumes from Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus may show promising signs of life

- Titan, a moon with familiar vistas

- What would it be like to stand on the surface of Titan?

- Dragonfly, NASA's mission to Saturn's moon Titan

- Triton, Neptune's largest moon

- Is life possible on rogue planets and moons?

- The Voyager missions

- Planetary Radio: Galileo at 30: How a mission transformed our understanding of Jupiter

- Cassini, the mission that revealed Saturn

- New Horizons, exploring Pluto and the Kuiper Belt

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Downlink

Transcript

Mat Kaplan:

Which moon is your favorite? We'll help you decide on this week's Planetary Radio Book Club Edition. Welcome readers of books about our solar system and The Cosmos Beyond. I'm Mat Kaplan, senior communications advisor for The Planetary Society and former host of Planetary Radio. We're keeping it in the family this time as we welcome our beloved colleague, Kate Howells. It's Kate's new book, her second, that we made our October 2025 selection, and it's mostly what we'll talk about today. That book is titled Moons: The Mysteries and Marvels of Our Solar System. You can watch the video of our conversation on The Planetary Society website. We've got that link on this episode's page at planetary.org/radio.

That said, we can dive right into the live conversation I had with Kate in The Planetary Society member community. Hey, everybody. We're back. It's The Planetary Society Book Club. Welcoming you once again. Here we are with our special guest for this evening. Someone who should be familiar to at least some of you, Kate Howells, my wonderful colleague. Science communicator extraordinaire is the society's public education specialist. That title really only begins to describe all that she does and has done for you folks, our members, and for others. Do you read our excellent newsletter, The Downlink? Well, that's Kate. She puts that together every week.

I'm especially impressed though by her service as the editor of The Planetary Report, our award-winning print and digital magazine. I also want to tell you that I really believe that you very admirably hold up a tradition, the creation of the magazine, that goes back to the very beginning of the society and its very first editor, Charlene Anderson, our associate director of the Society, long retired now. But she is also the person who was my first boss at The Planetary Society. And I can tell you, you have reason to be very proud to be continuing that tradition, Kate.

Kate Howells: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan:

So, let's talk about her books because it is plural. Moons is not Kate's first book. I can't say her first book's full title without having to change our status as a kid-friendly service. So, use your imagination as I call it. Space is cool as a 4-letter word for an intimate activity. And it really is cool. Yeah, space, but the book is amazing. It's a graphical wonder full of amazing art and very entertaining text and just chockfull of that old PB&J, that passion, beauty, and joy for space exploration and science that all of us love.

Parents, you may want to wait a few years before giving it to your space-crazed 6-year-old, but none of that is true for this book, which is the one that we will be talking about over the next hour or so. It is called Moons: The Mysteries and Marvels of Our Solar System, and it has been created by my colleague, Kate Howells. Kate, it is great fun. Thank you so much for doing this and for joining us this evening.

Kate Howells: Thank you. It's truly an honor to be the book club author and not just behind the scenes sharing out the book club links and promoting it and following along with your conversations with others.

Mat Kaplan: Well, it's well deserved, of course. What led to creating this great book?

Kate Howells:

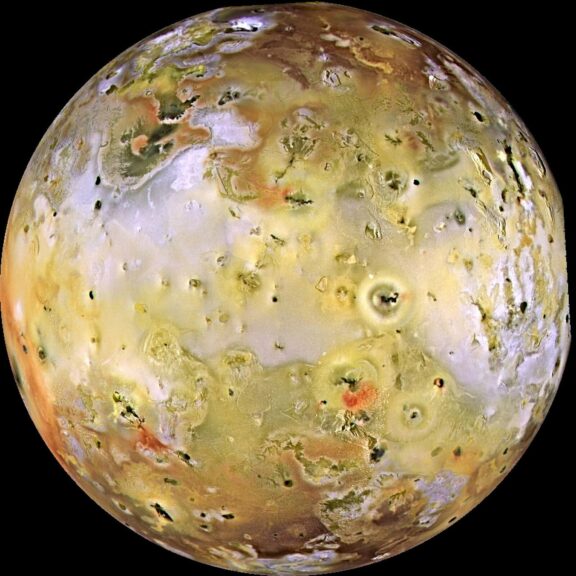

The moons of the solar system were one of the first things that I learned about that really got my imagination going. And I was actually reading Carl Sagan's Cosmos that did it because he describes the Voyager mission in all its glory, but one of the things that really struck me was what Voyager discovered about the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. And I read this before I was in the space biz. I hadn't really studied space beyond elementary school. And you don't learn about the moons other than Earth's moon if you're not really learning more than what's in just average school curriculums. And so, this was brand new information to me and I was blown away. I saw photos from Voyager of Io with all of its volcanoes.

I was like, "What? This is so cool. This is so much cooler than..." I mean, the planets are great, don't get me wrong, but the moons really were just this amazing discovery. And I thought a lot of people probably don't know about these incredibly cool worlds and how much promise they have for the search for life, but also just for understanding the diversity of planetary bodies that is out there in the universe. So, I'd always had this idea that a book about moons could be the perfect low hanging fruit for people who don't know a lot about space already. And I always try to write in a style that's accessible and aim towards people who maybe are a little wary of delving into a scientific topic.

I myself was not a big science person until my early '20s really. So, I understand that perspective of thinking like, "Oh, math is hard and I didn't do well in chemistry, so maybe I shouldn't voyage into scientific topics." But so my admission now is to change people's minds who might think that way as well. And I think moons are a great way to do that.

Mat Kaplan: I couldn't agree more on your living proof that you don't have to start when you're six or seven as a space nerd or space geek. You open the book with this great anecdote and it's two shopping channel hosts who are clueless. Tell us a little bit about that. Talk about that.

Kate Howells:

Yeah, it's this hilarious clip that I saw on YouTube years ago and yeah, it's shopping channel-hosts and they're talking about a blouse that it's got a better like this. And they say, it looks like the planet moon from a great distance. And the other one said, "The moon's not a planet. It's a star." And they say, "No, the mood's not a star. What are you talking about? It's a planet." And then they have this back and forth where they're arguing and they're like, "Well then, but the sun is a star. Isn't the moon like the sun?" And Don says, "No, no, darling. The moon is totally a planet."

And then they have their producer Google it and the producer gives them this definition of the moon is a moon. The moon is a natural satellite, and they're just more lost than they were before. And they continue back and forth and then they eventually just go back to talking about the clothes. And I think it's such a great encapsulation of a lot of people's very benign ignorance. A lot of people don't know what the moon is. Our moon, the moon that you see in the sky and they think there's the night sun or it's equivalent.

And I think it's so remarkable and there's no disrespect intended towards anybody who doesn't know this stuff already because again, you only know what you know and you don't necessarily get opportunities to learn everything. So, it's no shade, but it's funny to me that there's this great example of people just having no clue what the moon is. So, that's my starting point of like, all right, let's talk about what the moon is. Let's talk about what other moons are.

Mat Kaplan: The vast majority of all the humans who ever lived didn't know what was really going on with the moon, didn't even know that it wasn't shining from its own light, that it was reflected from the sun. So, anybody out there who may still have a misunderstanding about our big natural satellite, they're in good company. Of course, our moon, it is one of the major ones that you talk about in the book, but there are lots of others. You have also ran your honorable mentions at the end of the book, but how did you decide among the now hundreds of moons and more every year across our solar system, how'd you decide which ones to give the most attention to?

Kate Howells:

Well, it came down to which ones have the most going on and that tends to be the bigger moons. They tend to have more interesting geology and some of them have an atmosphere or a magnetic field. And so, there's more to talk about with the bigger moons, but then especially in the honorable mentions, you get the smaller ones that are interesting for some reason or another, like Pan, the little dumpling moon, for example. And I did, I think the smallest moons that I give a full chapter to are Mars' moons because again, they're interesting in their own right because of how they formed and how they might get disintegrated into a ring system in the future and how they might factor into Mars exploration.

And then you get the chance to talk a little bit about Mars and why we want to explore there. Yeah, it came down to which ones had the most material really available about them. That is to say, I'm sure there are a lot of moon researchers who will read my book and say, "Wow, you missed so much cool stuff about whatever X, Y, Z tiny little moon." And I'll have to do a sequel.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, there's an idea. Hey folks, tell us your favorite moons, whether they're in the book or not. Add those to the chat and we will be sure to talk about those. I think you made great choices. I want to start talking about some of these and we can start right where you do in the book, which is one of my two favorite moons across the solar system. You featured both of them in the longer essays that you did. Is Jupiter's Io also at or near the top of your list?

Kate Howells:

Yes. Io was my favorite moon for a long time because it's shocking. It's unlike any other planetary body that we know of and it's terrifying and it's intense. And it just, it was one of the first moons that I learned about where I really thought, "Holy smokes, there's a lot going on out there that's really wild." For those who don't know Io is it's the most volcanically active body in the solar system. So, it has hundreds of volcanoes across its surface, erupting basically nonstop, huge lakes of lava, eruptions of lava, but also gases that spew hundreds of kilometers into space.

It is a chaotic nightmare of a place and it's just completely awesome. Yeah. It's no longer my top favorite, but it was for a long time.

Mat Kaplan: And I have always loved it. I mean, since we learned its true nature, which started back in the Galileo days when Galileo was orbiting Jupiter and certainly was vastly amplified by Voyager. Now, I mean, for a lay person, I know a fair amount about what's going on across the solar system, but the book still had a whole bunch of really interesting facts that were stunning to me. And one of the ones in this chapter about Io is that with its more than 400 volcanoes, you said that it's more than a hundred times more lava than all of our earthbound volcanoes combine, which just blows me away.

Kate Howells:

Yeah. Again, it's just shocking. Everything, and I don't have a great memory for numbers, so I won't try to quote specific numbers that I mentioned in the book here right now, because I'll get them wrong. But the numbers on Io are crazy where, yeah, the volume of lava, the heat of the lava, how high up it all shoots out of the volcanoes, it's way beyond what we see on earth. And it has a lot to do with the fact that Io's just so much smaller. So, for example, with like lava flows that can go much, much further and shoot much higher, there isn't the same like gravitational pull slowing everything down that we have on earth because earth is just like so much enormously bigger than Io.

And so, you get these different dynamics because of the different nature of the celestial body itself. And that leads to these really wild phenomena that you see on Io, which is, again, it's just really cool. You learn these little facts and then you learn about why they happen and that in itself is cool and surprising. And yeah, I will say I also didn't know everything that I wrote in this book until I was researching it. I picked moons and I chose specific bodies because of what I already knew. But then in researching, I just discovered so much more. And it was such an enriching process for me personally to just dive deeper and deeper into all of these different bodies.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, talk about stuff shooting up. I also learned from the book that, yeah, the lava goes pretty high, but the gas coming out of these volcanoes, 500 kilometers beyond the surface, which is mind-blowing.

Kate Howells: It's bonkers. I mean, thinking about being on the surface of another celestial body is always interesting, trying to picture yourself there. And Io's a great one. I mean, you have to just assume that you're very well protected somehow from the extreme conditions, but yeah, if you imagine like the International Space Station orbits earth at what, like 100 kilometers above the surface to... I get the numbers...

Mat Kaplan: More than that, more than that. I think it's, oh God, somebody can correct us. It's at least 200 kilometers and micro 400.

Kate Howells: Okay. So, let's say, it's 200 geysers of gas shooting twice that high from the surface. I mean, you can't imagine what that would actually look like to be standing next to one of these geysers looking at it shooting that high and then seeing Jupiter in the background. I mean, it's great fodder for the imagination.

Mat Kaplan: Which is a great lead in to something else that I wanted to talk about anyway, because here and there in the book, the book is richly illustrated far beyond these original illustrations or paintings, but there are these full page illustrations by the artist Gordon Ald?

Kate Howells: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: Did I pronounce it correctly? The one for Io, here it is right in line with what you were just talking about. This is nuts. I mean, this is one suicidal astronaut. It reminds me of that epic battle, episode three of Star Wars, Obi-Wan and Anakin, rolling around a few inches from lava, and then of course Anakin ends up in it. Except in your book, it's this astronaut risking life and limb for science, which is pretty cool. I mean, tell us a little bit about Gordon and how he ended up doing these great illustrations. We got one more that we'll show a little bit later.

Kate Howells:

Gord is a good friend of mine. We've been friends since high school actually, and he's just a really talented artist. And as long as I've known him, he's enjoyed drawing spacey, sciencey kind of things. So, I actually worked with him on the Spaces Cool book and he did some illustrations for that. And then he's done illustrations for The Planetary Society as well and he's just great to work with and he's a good friend that I see all the time. So, I'll just text him, "Hey Gord, you want to draw Io?" And he's like, "Sure, yeah." And yeah, the reason that I wanted to have illustrations and not just real space images is that I did want to try to capture things that we know to be true, but that we don't have direct images of.

So, things like being on the surface of Titan and what that might look like, we can piece together an imagined view based on the science we know. And of course, he takes artistic liberties and that's all fine. Nobody should expect this to be perfectly accurate, but for all of the illustrations, it's to try to give you a glimpse into what you could imagine it would be like to be there. So, almost all of them have an astronaut present somewhere in the illustration to just give you a sense of the imagined view that you could have if somehow you were able to be there.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. And the human experience of it. And it also just the scale that it adds to these fanciful images. Before we move out one moon and one chapter, I'm going to read some stuff from other members that is coming in. John says, "Saturn's moon hyperion's exotic appearance has always fascinated me. It looks freezer burned." I think it's one of your also rans. Phil, Phillip says his favorite moon is Europa, which is exactly where we're going next, Phillip. So, good timing. He says he loves how Enceladus has fountains like Las Vegas. Yeah, I've been in front of the Bellagio Hotel in Vegas, Phillip, and it ain't the same. I mean, I'd love someday to be out there looking at those.

Kate Howells: Vegas wishes it had the fountains of Enceladus.

Mat Kaplan: So, if we go out and move out that one orbit also at Jupiter, we do end up at Europa. I wonder, Kate, what your thoughts are about the visitor that is on its way there right now, Europa Clipper, which is fingers crossed, going to get there in 2030.

Kate Howells:

Oh yes, very exciting. I mean, I have not been in the biz as long as you have, Matt, but I've been there long enough now to remember the origins of missions like Europa Clipper where they say, "Oh, we want to send a mission to Europa." And then The Planetary Society advocates so hard to make it happen and then it gets approved and then it gets built and then it launches and now it's on its way. And it's wild when you, like the timescales that these missions take to go from conception to launch, but then the travel time is so huge as well. You have to be very patient to be interested in space exploration, but it's thrilling to know that it's on its way.

I'm very optimistic that Europa Clipper will make discoveries that prompt new questions. I don't necessarily think, "Oh, it's going to find the conclusive sign of life because I think the science community is very cautious." And so, what I hope it will find is something like what Perseverance found on Mars with the Cheyava Falls sample where you see something that's so tantalizing and intriguing that it prompts further study. So, more missions that have the tools to do more, something like a Europa sample return. I'm so excited for it to push the science forward.

Mat Kaplan:

I'm really hoping that Europa Clipper outperforms even what its team says and find some just ridiculously long organic molecules. And then really, how could we avoid going back and Digging a little bit? There's a key line that you use in this chapter about Europa, and we see it all the time. We hear it all the time. It applies to pretty much all of science. It starts, as is so often the case with space exploration, the little bit we've learned about Europa has opened up many more questions, which is exactly what we're talking about. I mean, my God, if we find those molecules or if we go down to the surface and find some fossil, wow.

I mean, you know that we're going to want to explore this brand new ecosystem, this new place where life has found a toehold.

Kate Howells: Absolutely. And yeah, we'll want to go off to the other icy moons as well and see what secrets they might be high because there's this whole collection of icy bodies that could potentially have the conditions for life under their surfaces, Enceladus being another key one. And yeah, imagine if we find something really tantalizing at Europa, what else might we find if we visit some of these other moons up close and study them?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, got to go to Enceladus as well. Another one of those great illustrations by Gordon is this one and here is a diver under the, what is it, 30 or so kilometers of ice swinging around. Did you notice, I wonder if you talked with Gordon about this. As he swims, he seems to be missing... There are a few little glowing spots, orange-ish spots behind him, which I think are worthy of investigation. And he ought to be swimming over that way.

Kate Howells: But imagine what he's swimming towards, or she or they, that's just out of view that maybe there's something even more tantalizing just ahead.

Mat Kaplan: Exactly right. Yeah, right. Maybe it's Europa under the water beckoning him to come on over. All right. We'll keep heading out because our time here is limited, of course, but we'll stay in the Galilean moons, get out past Ganymede, and we reach Callisto, the last of the Galilean moons. I didn't remember if I knew that it has what we think you mentioned in the book, the oldest surface in the solar system. And of course, when a surface is that old, it can teach us a lot.

Kate Howells: Yeah. Callisto, I always think of as almost like a disco ball because it's so peppered with impact craters that it has this disco ball-ish appearance. And again, it's just this diversity that you see even in just the Jovian system, just the moons around Jupiter, you've got Io, which is just this rock and lava hellscape, just completely insane. And then you have Europa, which is this serene smooth, I think the smoothest surface in the solar system are one of them.

Mat Kaplan: I think you're right.

Kate Howells: And then Callisto is this pockmarked crazy place. So, even within such a small area, you have, I mean, huge, but relatively small, you have so much diversity. And that is one of my favorite things about learning about the moons of the solar system is just seeing how many different types of world there can be even just in our solar system.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. I think it's one of the greatest discoveries that we've made because I mean, there was a point when they thought, okay, they're all going to look like our moon. No. And yeah, you can even extend it out to Pluto, which is moon sized. And look what the surprise that we got there when New Horizons made its fly by.

Kate Howells: Yeah. I dare you to find a boring celestial body. I don't think that they exist.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to read some more messages in the chat window from our members who have joined us live. Mike quotes... This is very appropriate. Mike says, quoting Arthur C. Clark, "All these worlds are yours except Europa." Attempt no landings there, of course from the classic 2010, Arthur C. Clark gave us the sequel to 2001. Sorry, Arthur and Space Child, we're headed your way. Adrian says, "International Space Station orbits earth at an altitude," okay, I was almost right, "between approximately 413 and 422 kilometers." For some reason, 400 sounded right to me. So, there you go. Thank you.

Kate Howells: Well, like I said, my memory for numbers is astonishingly poor, so I apologize.

Mat Kaplan:

It's like my memory for names. Phillip, who we heard from earlier, was just complimenting the illustration, said beautiful illustration. Adrian came back and said the radiation at Io would kill him, your suicidal astronaut in short order. Radiation flux is 3,600 rem per day. That's lethal to humans within minutes, which of course is why everything that goes out and spends any time in the vicinity of Jupiter has to be very carefully shielded. Thank God Europa Clipper has most of its electronics inside that vault, that very thick vault. And we know because Juno used the same system and it's still going strong that it's going to... Well, we hope it'll be just fine because we sure want to get those results.

All right, now we can move back out. Let's see. Let's go out to Saturn, jump out one big world to another tiny world Enceladus, tiny, but full of surprises, isn't it?

Kate Howells: Absolutely. This is another icy moon with a subsurface ocean that shows all the signs of being very friendly to life and extremely tantalizing because of its enormous geysers that shoot out of its South Pole where you could conceivably fly through a plume and see what you get. And it's a lot more active, the geysers than Europa. So, part of me is like, "Oh, can't we just redirect Europa Clipper?"

Mat Kaplan: I had the same thought. Yeah.

Kate Howells:

Yeah. But we'll just have to send another mission. But yeah, another just beautiful and fascinating place that has such intrigue, the questions that we could answer if we were able to just get there. And it's just a shame that all these places are so far away and that it takes so much work and so much money and effort and time to get there because otherwise, I mean, if we lived in a different world, perhaps we would have probes out at all of these places already, but I would definitely put Enceladus at the top of my list, even though there are other places that I think are maybe more interesting in other ways.

But in terms of the search for life, which is just such a huge driver, such an important endeavor, I think Enceladus is tippy top of the list.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. I couldn't agree more. Like you and so many people out there, all our members, at least we had Cassini-Huygens and I know you and so many have a special fondness for that mission. I certainly do that it explored Saturn and its rings and moons and it just, the mission ended. It's hard to believe it's been eight years already, just over eight years. You talk about the discovery by Cassini of those wonderful plumes and how the team figured out how to learn more about them, the way they actually repurposed an instrument that wasn't designed to tell us about the plumes, right?

Kate Howells:

Yeah. I mean, half of what I love about space exploration is just the human ingenuity. The worlds that we're studying are really cool, but the things that humans achieve... And to go back to my origin story of reading Cosmos and being completely enraptured, a big part of that for me was learning about the Voyager missions and like how humans were able to calculate these trajectories and send these spacecraft off to do all this exploration and that they're still functioning decades later.

I mean, that really blew my mind and it's still to this day, the ability of scientists and engineers and technicians, the people working behind missions, what they can do, they can juice these missions for so much more than you ever would have thought possible. And I just think that that's so impressive and cool and worth celebrating.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. And it has been almost the rule across all of these successful planetary science missions across the solar system. All right, we got to keep moving out there, heading out in the solar system. You surprised me. You visit Neptune, Neptune's Moon Triton. I thought we'd stick around at Saturn. Thank goodness I was relieved when you took us back to Titan a few pages later because it's my other favorite moon. It's hard to choose though, but Triton, right? crazy place.

Kate Howells: First of all, beautiful. One of the most aesthetically pleasing moons, I would say. It looks just like a snow cone or an Easter ice cream cake or something. It's beautiful and it's another place that we've barely studied. It was voyager one or two numbers that flew fast. And like we just got this quick fly by and what we learned, again, just brought up so many questions that we just need answers to, but when are we ever going to head back there? I know that there are missions on the table to head back out into the outer solar system, but yeah, Triton is so fascinating. The idea that it might be a captured planet, just fascinating and beautiful. Love Triton.

Mat Kaplan: And I know China is at least talking about a mission to Neptune. Of course, the farther out you go, the longer it takes to get there. So, we're talking about stuff that is years away, even assuming that we reach a launch. But we know so many people in the planetary science community who have been lobbying for decades to head back out there and add to that very brief flyby we had from Voyager. There is an area, a section of Triton, which is one of the things that makes it so interesting. And you probably know the one I'm about to talk about. It's the cantaloupe terrain, which you have a good image of in the book.

Kate Howells: Yeah. I mean, again, I love scientists. I love that they see something that looks a bit like Cantaloupe and now it's called Cantaloupe Terrain.

Mat Kaplan: Very scientific name.

Kate Howells: Yeah. When you're discovering things that no one else has ever seen before, you get the privilege of naming it whatever you want. And I think space scientists especially have a knack for creative and charming names, like even just thinking about the Big Bang, that we call it the Big Bang. I mean, it's wonderful. So, yeah, Cantaloupe Terrain as well as one of those. And yeah, it's again, this intriguing thing that we just need to learn more about.

Mat Kaplan: That's my Planetary Society colleague, Kate Howells. Many more moons await us after this brief break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here, CEO of The Planetary Society. We are a community of people dedicated to the scientific exploration of space. We're explorers dedicated to making the future better for all humankind. Now as the world's largest independent space organization, we are rallying public support for space exploration, making sure that there is real funding, especially for NASA science. And we've had some success during this challenging year, but along with advocacy, we have our STEP initiative and our NEO Shoemaker grants. So, please support us. We want to finish 2025 strong and keep that momentum going into 2026. So, check us out at planetary.org/planetaryfund today. Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: The next chapter, you take us back inward in the solar system to our own moon. The one that is the moon with a capital M, unless you want to call it Luna, like a lot of science fiction people do. I'd read about how most people, most scientists now believe there's still some question about this, that it was formed after this tremendous impact on the primordial earth. But I was shocked to read in your book that the moon may have come together very, very quickly.

Kate Howells:

Yeah. I will say right off the bat that working on the chapter on Earth's moon was the most eyeopening because I knew some things about the moon, but I always thought it was a boring moon compared to explosive Io or tantalizing Enceladus. But Earth's moon is super fascinating. And I am really glad to have done this research and developed this appreciation because now I can look up in the sky and see it and think, "Oh, that was covered in volcanoes for years." Because yeah, it was formed by this impact, they think, between a protoplanet about the size of Mars and pre-earth. And the debris kicked up by that impact, coalesced in a matter of potentially even less time.

And this created so much heat that the moon was just the molten ball of lava for millions of years and...

Mat Kaplan: Millions, millions and millions, many millions.

Kate Howells:

And then now when you look up at the moon and you see the dark splotches, that those are volcanic basins because the moon was covered in active volcanoes for millions of years, right up until the timeline is like a little bit close. And I've talked to Bruce Betts, our chief scientist about this, because the moon was volcanically active until right about the same time that the dinosaurs started to rule the earth. And there's questions about how active was it and how many dinosaurs were there. But there is evidence of a little bit of overlap. And I love the idea of dinosaurs looking up and seeing volcanoes exploding on the moon. But anyway, the moon has this incredible history.

I've written about it for the planetary report as well. There was so much more going on than you ever would have guessed. You always just think of it as this stable inert body, but it had a lot going on and it still has a lot going on. There are still really interesting places on the moon like the lava tubes where lava once flowed and then rock formed around it and then the lava drained out, and there are these tubes that could fit entire cities inside them and compared to lava tubes on earth that never get much bigger than like your average sort of underground tunnel for vehicles.

It's just so interesting. And again, it's just such great fodder for the imagination.

Mat Kaplan: Wouldn't you like to walk around in one of those lava tubes with an appropriate spacesuit? I mean...

Kate Howells: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: And of course, maybe someday there will be a city or at least a settlement or an outpost in one of those because they provide some protection from the radiation. So, I know it's been talked about.

Kate Howells: We have to just stop cutting NASA's funding and we will eventually get there.

Mat Kaplan: Start. Yeah. Right. Absolutely. As a side note, you have sidebars in the book here and there. You address moon landing conspiracies in one of these sidebars, which somehow continue even as we get photos back from orbit looking down at the descent stages of the Apollo landers and tracks left by the Apollo moon buggies. It makes me nuts. And our friend Phil Plait, the bad astronomer, just today in his newsletter, put out a piece, his blog about Kim Kardashian apparently now. I haven't read it yet, but apparently she's pushing the moon conspiracy conspiracy. It just drives me crazy.

Kate Howells:

I think, again, I think it's this fairly common ignorance. Ignorance sounds like such a judgmental word, but I genuinely do feel like a lot of people just don't get opportunities to learn about all the things that we get to learn about. And if you don't even really know what a moon is, of course you might believe that the moon landings were a hoax. I think it's one of those things where, as soon as you actually learn about what's going on, you ought to see that it definitely happened. And we have rocks. We have lunar rocks here on earth that the astronauts brought back and that we're studying.

And the idea that there's this massive conspiracy that goes all the way down to grad students working on research on these samples and that, oh, they're in on it too. And the idea that that many people could keep this big secret is honestly putting a lot of faith in humanity's ability to organize. And I don't know if that faith is warranted. Yeah, it's a strange one. So, yeah, I do always like to put out good information that people can equip themselves with if they find themselves in a conversation with a moon landing denier.

Mat Kaplan: Yep. Which I have been on occasion and probably will again, maybe we all have.

Kate Howells: Yeah. Is the earth flat or have aliens come to earth and did we actually land on the moon? Those are the big three that you're going to encounter, especially when you work in the space biz and people say, "Oh yeah, you do space stuff, right?" Well, I'm pretty sure I saw a UFO and you go, "Okay, okay. Yeah, we can talk about that."

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. John has a question for you. He says, "Kate, which solar system moon would you actually bet money on being the one where we discover life, be it microscopic or larger"?

Kate Howells: Hmm, that's an interesting question. I think, okay, I'll answer it as though we had infinite money to send missions to all of the moons, I would probably say Enceladus. However, my optimistic side/the marriage of my optimistic side and my realist side, which says we've got a mission en route to Europa already. So, that increases its chances realistically and hopefully, optimistically, maybe multiple moons have life. And so, we're more likely to discover it at Europa because we're going there first. So, I'm torn, but I think if I just said, which one do I think has signs of life, most likely it would be Enceladus.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Adrian comes back and says, "Voyager is now almost one light day away from us." Indeed, it is. In fact, we are about one year away from Voyager reaching that milestone or kilometer stone was what our boss, Bill Nye would probably say. And I sure hope that there's going to be a great celebration of that, which means that things are going to have to turn around some at NASA because most of the news out of NASA and JPL right now is not great, but that's going to be worth celebrating.

Kate Howells: I can promise The Planetary Society will celebrate that.

Mat Kaplan:

Yeah, that's what I'm pushing for. Well, I don't want to give anything away. There are people who, I will say, who are on the Voyager team who would love to have us as a part of that celebration. As we have been a part of past celebrations of Voyager, going all the way back to Carl Sagan on stage with Chuck Berry. After all, Chuck Berry is on the golden record and we know the aliens in, I don't know, several hundred thousand years are going to send back a message, send more Chuck Berry. Let's get to that last moon world that you devote a lot of extra space to. And it's my other favorite, as I said, Titan, so we head back to Saturn.

It earns my love in so many ways. As you point out, its surface features are named after locations in the Lord of the Rings and Dune. We are such nerds.

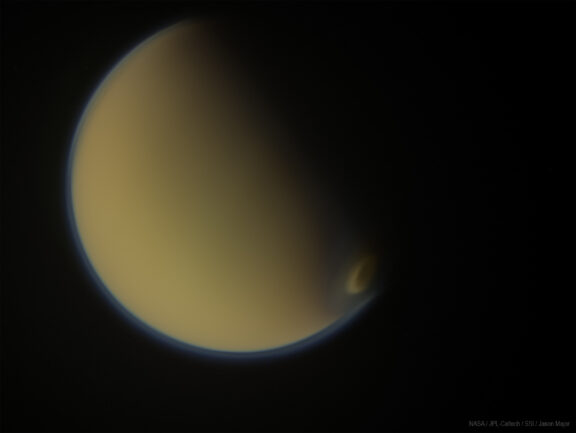

Kate Howells: Yes. Oh, yes. I absolutely love that. Yeah. Titan became my favorite moon pretty early on and has just like learning more about it to research for this book just cemented its place at the top because it's the most alien, like sci-fi type alien world that I've ever come across. I mean, we hear about exoplanets where it like rains diamonds and stuff, but in terms of our local neighborhood, Titan is the stuff of science fiction. It's incredible. Yes, it's the only other body in the solar system that has stable liquids on its surface. It's got rivers and lakes and rain and seas, but it's all liquid methane and ethane, which is mind-boggling on its own.

Mat Kaplan: Crazy stuff.

Kate Howells: The idea that there's this whole equivalent of like the water cycle. I talk about this in the book, you learn in school about evaporation and condensation and precipitation and then rivers eroding down mountains and collecting in lakes and then evaporating again and all that's happening, but with methane, but it's cold enough that it's in its liquid form. That is just so cool on so many levels. And then yes, of course, the fact that these features are named after just the nerdiest stuff you possibly could, that speaks to my heart. My dog's name is Gimli, son of Glóin, like this is...

Mat Kaplan: No kidding.

Kate Howells:

This is my cup of tea. It's just delightful. And then yeah, learning about the... There's huge fields of dunes of hydrocarbon. So, it looks like coffee grounds and it's basically sand grains, but that aren't formed from erosion. So, sand grains on earth are from bigger things being broken down into tiny grains, but on titan, it's tiny particles of almost like smoke particles that come together and clump into these grains. So, it's just this totally alien sand basically. And then yeah, it's got this super thick atmosphere, but the gravity of Titan is low enough that you could conceivably flap wings.

If you had basically like arm sized wings, like you saw back in the olden days when they're trying to learn how to fly on earth, and there's old-timey videos of people flapping their wings and jumping off hills. If you did that on Titan, you could actually fly. And it's the easiest place in the solar system for flight because of its low gravity and its high atmospheric density and we're sending a flying spacecraft there, like a gigantic version of ingenuity with more rotors and it's going to fly around. It's just, it's the coolest stuff. It's hands down the coolest place and I just love it. And so, yes, I gave it the most space in the book and it gets the final big chapter because it's the home run moon, I think.

Mat Kaplan: I am hoping and praying that we will see Dragonfly, that octocopter launch on time in 2027, because even leaving then, it's not going to reach Titan until 2034, but what is lighting mission?

Kate Howells: Yeah, it's going to be so cool. I almost wish it had a little companion spacecraft to take photos of it in flight because we're just going to have to use our imaginations for that. But yeah, boy, what a cool mission, what a cool moon.

Mat Kaplan: I know it has a ton of cameras all over it, so hopefully, and I'm sure they're planning to get some video back from that.

Kate Howells: If Perseverance can take a selfie, maybe so can Dragonfly.

Mat Kaplan: So, Adrian looked it up and said, "Yeah, Voyager one is the one that's going to reach one light day away in November, almost exactly one year." And that's the one we hope we're-

Kate Howells: Very cool.

Mat Kaplan: ... going to be celebrating. Dave said, "I don't believe in moon landing deniers." I wish I could say that, but I've met too many of them, Dave. So, the book doesn't end with Titan. As we said, you've got these honorable mentioned moons. I want to ask you about your favorites or most intriguing among them. I already mentioned Hyperion. The phobia that I think I really do have a mild case of is called Trypophobia: The Fear of Objects with Clusters of Holes.

Kate Howells: Yeah, I think that's a fairly common phobia. I've encountered a lot of people who have it and it does not resonate with me. I don't get what's scary about that, but I respect it.

Mat Kaplan: Lucky you. Yeah, that's great.

Kate Howells: I like Hyperion. Again, it just looks really cool. It's very different. It brings up all these questions of like, how and why does this moon look like a big sponge? Because it really does. It looks like those like the natural sea sponges. It just looks like somebody hucked one of those into space and left it there. And I just think that's really neat. And it's like the least dense object in the solar system or something. It's such a cool little world. And yes, I also, I do love pan, the tiny little dumpling moon that looks like somebody hucked a piece of ravioli out into space. And I love Miranda, the moon of Uranus that has The tallest cliff in the solar system and where the gravity... Again, I shouldn't cite things that involve numbers. Read the book and you'll see there are some shocking numbers about if you were to drop a rock off the top of that cliff, it would take a shockingly long time to fall to the ground because the cliff is so huge and the gravity is so low. And it's just neat little things like that that, again, the numbers don't stick in my brain, but the general idea does, because it's just amazing and cool and worth spreading around.

Mat Kaplan: There is a wonderful old CGI video done a fair number of years ago now, but beautifully done. And it shows humans all over the solar system doing crazy things like jumping off that cliff on Miranda and floating on around-

Kate Howells: That's awesome.

Mat Kaplan: ... the surface. Man, won't be in my time, won't be in the time maybe of anyone alive today, but we have quite a future to look forward to across the solar system. David talks about Charon larger compared to Pluto than our moon is to earth, just proportionately. And then he adds, is Pluto a planet. We won't get into that one right now, but Charon is one heck of a moon.

Kate Howells: Yeah. I think I actually do talk a little bit in the mini chapter, the honorable mention about Charon, that size difference and the way that they orbit each other instead of one clearly orbiting the other is part of the reason why Pluto is not a planet anymore, it's not considered a planet anymore. So, it's part of that whole, some say controversy of Pluto's demotion.

Mat Kaplan: The center of gravity is not inside Pluto, the center of gravity of the two bodies, and that's one of the reasons it got downgraded, but don't say that to some of our favorite scientists, our favorite planetary scientists.

Kate Howells:

Yes, I'm actually at sneak preview. I'm working on the March issue of the Planetary Report right now, and we're going to be talking about dwarf planets in one of the features. And something that I always like to say when talking about Pluto being demoted is that it actually just became the most famous of the dwarf planets. It got Bumped up to the top of the list in a lot of ways because yeah, now it's the king of the dwarf planets and everybody's favorite dwarf planet. And also by being... I still, I'll use the term demoted regardless, but by being demoted, it brought attention to all the other dwarf planets.

And I think that that is actually a really valuable thing because again, like moons, dwarf planets are a really interesting category of world and there are a lot of interesting things going on out there and people should not only care about planets. So, I'm pro-Pluto as a dwarf planet, even though I know that there are lots of people who strongly disagree and you can come for me in the comments.

Mat Kaplan: You finally in the book take us across the light years. We leave the solar system and you talk about exomoons, circling exoplanets, which we now know there are thousands and thousands of them. I think we just hit 5,000 confirmed exoplanets. Pretty much every star has at least one planet and a whole bunch of moons out there. So, we've started to find exomoons as well, right?

Kate Howells:

Yeah. And this is another thing that just boggles the mind because when you think about the number of moons in our solar system and the chances that any of them could be habitable, it really, really expands what we... Like when we think about there in other star systems, how many worlds there are that could be home to life just exponentially increases when you realize that moons could just as easily be home to life as planets. And again, I keep going back to Carl Sagan. I mean, he was just the biggest influence on me ever. And in his day, people didn't know if there were exoplanets. They were theorized.

They thought that surely there must be planets around other stars, but there wasn't direct confirmation of exoplanets until fairly recently and now we... Yeah, like you said, we know that they're out there around pretty much every star. And when you think about just the implications of those numbers and then the number of moons compared to the number of planets in a given solar system, it really is basically impossible that life doesn't exist out there, which I think is one of the most important and fascinating questions in space science. So, exomoons, I think are something that we're going to learn more and more about over the coming decades as the technological ability to study them advances.

Even with new space telescopes coming online in recent years, our ability to study these things is really growing. And I think that that's where a lot of the most interesting science is going to come in the coming years.

Mat Kaplan:

I want to meet some of those very tall blue people with tales that live on the exomoon Pandora someday. Let me get to a last round of questions and comments from our wonderful members. And one of them is a dear old friend of mine, Larry is out there. He says, Personally, I'm excited about the prospect of liquid water on Europa under all that ice where it would be protected from the Jovian radiation. Fingers crossed, Larry. John says," My Christmas list now includes Kate's book. "Thank you, Mat and thank you Kate," says John. "David, if you don't want to debate about planet hood for Pluto, how about Karen versus Charon as a pronunciation for that moon of Pluto?

Good one, Dave. You're right. The other Dave says," If our moon as the same size of earth, which one would be considered the moon? If our moon was the same size as earth, would they be a double planet, a double dwarf planet or a twin moon? "Not being a planetary scientist, Dave, I think I will leave that to our betters who actually have that expertise, but wouldn't that be interesting?

Kate Howells: One thing I will say on that note is that the earth's moon is not nearly as large as earth, but it has the biggest size ratio. So, there aren't any planets in our solar system that have a moon as big relative to the planet as earth's moon is to earth. So, it's as close as you really get to a full-blown planet having a big moon, I guess, unless you considered Pluto a planet, but we're not getting back into that debate.

Mat Kaplan: So, that's a win for the Earth Moon system. Adrian looked into it or knew that actually if you had two worlds roughly the same size orbiting about each other, it's called a binary planet, planetary system, a binary planetary system. Makes sense, right? Okay. I want to get back to your life outside of writing books and doing all this great work for the society because you are a proud Canadian. Sorry about the Blue Jays. I really genuinely am sorry about that. I was pulling for them at the end, even though I'm an old Dodger fan, but just the same. You guys have so much to be proud of up there. You've had a little bit to do with the Canadian Space Program over the years. Can you talk about that?

Kate Howells:

Yeah. So, I was actually first hired to The Planetary Society to be a liaison into the Canadian space community. My role has shifted over the years. It's been about 12 years now since I was first hired. But yeah, my earlier part of my career was really deeply involved in the Canadian space community. We have a really strong space community here. It's a small space program, especially relative to NASA, but we punch above our weight, I would say. And yes, for a period, the Trudeau government introduced a space advisory board, which brought on experts from across different parts of the space sector to advise the government on what direction our space program should go in and what changes needed to be made on various levels.

And I had the enormous honor of being on that board. And so, I got to help people with a great deal more experience than me guide the space program for a few years. That board wrapped up its work a few years ago, but that was a really amazing experience and getting to really feel that the Canadian government values the perspective of the space community, whether that's policy, science, engineering, law. I was mostly on the board as a representative of the education and outreach side of things, but really seeing the government take all of these perspectives seriously to adjust the trajectory of the space program was really special.

And since then, I'm still very involved. I work with the Canadian branch of the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space, SEDS. So, SEDS exists in the US and we have SEDS Canada as well. And I'm involved with another fellowship program for young people getting involved in the space community called the Zenith Pathways Fellowship Program. I really, really do enjoy getting the opportunity to meet young people who are so passionate and so interested and want to contribute to Canada space program. We also, I think, could benefit from more funding. I mean, the US is dealing with this threat to what has been ample funding.

I would say compared to the rest of the world, NASA has been extremely well funded. And I think countries like Canada haven't had the benefit of huge budgets. So, I think there was so much more that we could do. Canada has never run its own independent planetary exploration mission. That being said, we've contributed to many, many international partnerships with NASA and with the European Space Agency and others to contribute instruments or pieces or the famous Canadarm, for example, on the shuttle and the International Space Station, but also instruments on scientific missions.

And I think that's something that allows Canada to have an important role in exploration and also give our students and our scientists opportunities to participate in the forefront of space science research. But I would love to see Canada have our own independent planetary exploration mission someday. And I think that's very possible with the talent and expertise that we have across the country.

Mat Kaplan: Is it the $5 Canadian bill that has the Canadarm on it?

Kate Howells: Yes. That just came out a few years ago and it's so special because yeah, Canada's money, Americans love to make fun of our money because it's different colors and it has animals on it and whatnot. And we have the loony and all that. But really, I think Canada's currency does a good job of celebrating things that Canadians are proud of. And yeah, the $5 bill has the Canadarm and an astronaut because Canada also has a strong astronaut program. We've been sending astronauts on shuttle and ISS missions for years. And we have an astronaut who will be flying on the Artemis two mission in the vicinity of the moon and come back to earth. Jeremy Hansen, who's actually spoken at a Planetary Society event before. We got a good relationship with them.

Mat Kaplan: I figured you're Toronto, right? When we did our big pent-up there?

Kate Howells: Yes. Yes. So, yeah, Canada does have a lot going on and I've always been proud of our program and it is good to see that the government recognizes that Canadians are very proud of what we do in space.

Mat Kaplan: Any nation that puts space technology on its money has got to be awesome. And I think across this last little bit more than an hour, you've seen plenty of evidence of Kate's awesomeness and why we are so glad to have her as a part of our staff, our mighty staff at The Planetary Society. But the book club is just going to keep trucking on in this grand tradition, which we have continued today with Kate Howells and her book, Moons: The Mysteries and Marvels of Our Solar System. Kate, thank you so much for the book and for all you do for us and for spending this time with us this evening.

Kate Howells: Thanks, Mat. Thanks everybody.

Mat Kaplan: Moons: The Mysteries and Marvels of Our Solar System is published by Lost the Plot. Yes, Lost the Plot. And you can find it in all the usual places. It's a delight, as is Kate Howell's, and so is Adam Frank. He'll be my next guest author here on the book club edition when we talk about Adam's latest, The Little Book of Aliens. Planetary Radio is a production of The Planetary Society. Our associate producers are Rae Paoletta and Mark Hilverda. Post-production is by Andrew Lucas. The society's member community is led by Ambre Trujillo. The producer and host of Planetary Radio is Sarah Al-Ahmed. I'm Mat Kaplan, Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth