Titan, a moon with familiar vistas

Highlights

- Titan is both the only other place in the Solar System with liquid on its surface and the only moon with a thick atmosphere, making it a tantalizing destination to search for life.

- Its rivers and lakes are made mostly of methane, and water plays the role of bedrock.

- NASA’s Dragonfly mission, consisting of a small rotorcraft, is planned to launch in 2027 to explore Titan.

Why we study Titan

Titan is Saturn’s largest moon, nearly the size of Mars, but it’s more than just a moon — it is a laboratory for life unlike anything we see on Earth. In a strange way, Titan may be the most Earth-like world out there. It is the only other place we know of that has liquid on its surface, but in Titan’s case the liquid is mostly methane, which fills up seas, flows in rivers, and even rains down from the sky. It’s so cold there that the mountains and valleys are sculpted from water ice as hard as stone.

But if humans were to journey to Titan, we wouldn’t need the bulky pressure suits that astronauts wear for spacewalks. That’s because, despite the moon’s weak gravity, the atmospheric pressure near its surface is about 60% higher than on Earth – it is the only moon in the Solar System with a substantial atmosphere. The atmosphere is mostly made of nitrogen with a small amount of methane, but near the top of the atmosphere, high-energy particles and radiation from the sun split these atoms apart. Their constituent parts react with one another to form a thick orange haze.

Carbon-rich compounds called tholins snow down from the haze onto the moon’s surface, building up huge dune fields in the flatlands. These tholins could be the building blocks of life – if it is possible to base life on liquid methane and ethane instead of water. If there is any liquid water on Titan, it must be buried deep beneath the frigid surface, hidden in impact craters, or erupted by strange, icy volcanoes. Because the primary surface liquid there is methane, one might expect any life that evolved there to be methane-based just as Earth life is water-based.

It’s not clear that Titan could host any living organisms, but the liquid on its surface makes it one of the most promising places in the Solar System to look. If there are signs of life there, it could be the key to understanding what ingredients are necessary for life to evolve and how it arose on Earth. It could tell us whether we should expect any life we find anywhere in the cosmos to be Earth-like, or we should discard all expectations and be open to the possibility of life vastly different from anything we’ve seen before.

Titan Facts

Surface temperature: -179 degrees Celsius (-290 degrees Fahrenheit)

Average distance from Sun: 9.5 AU

Diameter: 5,149 kilometers (3,200 miles)

Volume: 71.6 billion cubic kilometers (17.2 billion cubic miles), Earth’s moon could fit inside Titan about 3.3 times

Gravity: 1.35 m/s2

Solar day: 382 Earth hours

Solar year: 29 Earth years

Atmosphere: Very thick and hazy; mostly nitrogen with a small amount of methane

Missions to Titan

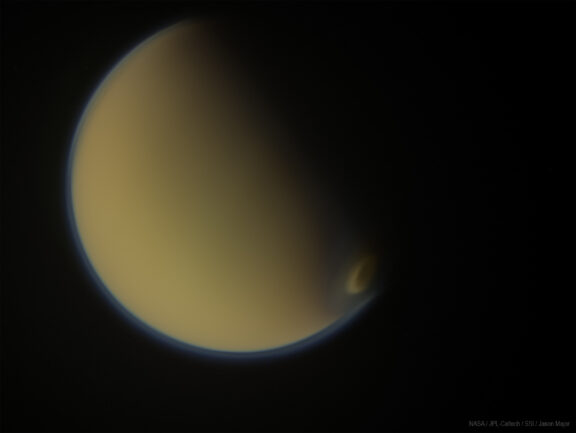

Titan’s thick atmosphere makes it extraordinarily difficult to study from afar. To most of our telescopes, it looks like a fuzzy orange ball. Before we sent the first spacecraft to study Titan up close, that opaque haze led many astronomers to believe it was the largest moon in the Solar System – a title actually held by Jupiter’s moon Ganymede.

The first three missions to visit – Pioneer 11, and Voyager 1 and 2, could not penetrate the haze, leaving Titan’s surface a mystery. Infrared light could pierce the atmosphere, so some images from the Hubble Space Telescope revealed vague areas that were brighter or darker than others, but it wasn’t entirely clear what those areas were until the Cassini mission.

The Cassini mission orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, and in that time it gave us nearly all of the information we have about Titan. It had infrared and radar instruments that allowed planetary scientists to see all the way to the huge moon’s surface during 127 flybys, and it also carried the Huygens probe. Cassini dropped Huygens through the haze to Titan’s surface, where it made the most distant spacecraft landing ever. It took valuable atmospheric data as it fell, and sent back pictures from Titan’s surface once it landed.

Now that we know about Titan’s methane seas and chemically complex atmosphere, NASA is preparing to take the exploration of this strange moon one step further with the Dragonfly mission, scheduled to launch in 2027. Dragonfly is a small drone designed to cover more ground than a traditional lander or rover by making short flights around Titan’s surface. Its main goals are to figure out whether Titan is, or ever has been, habitable, look for complex chemistry, and even check if there are signs that this hazy world has actually hosted life.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth