NASA discovers Mars rock with ancient potential for life

Written by

Asa Stahl, PhD

Science Editor, The Planetary Society

August 1, 2024

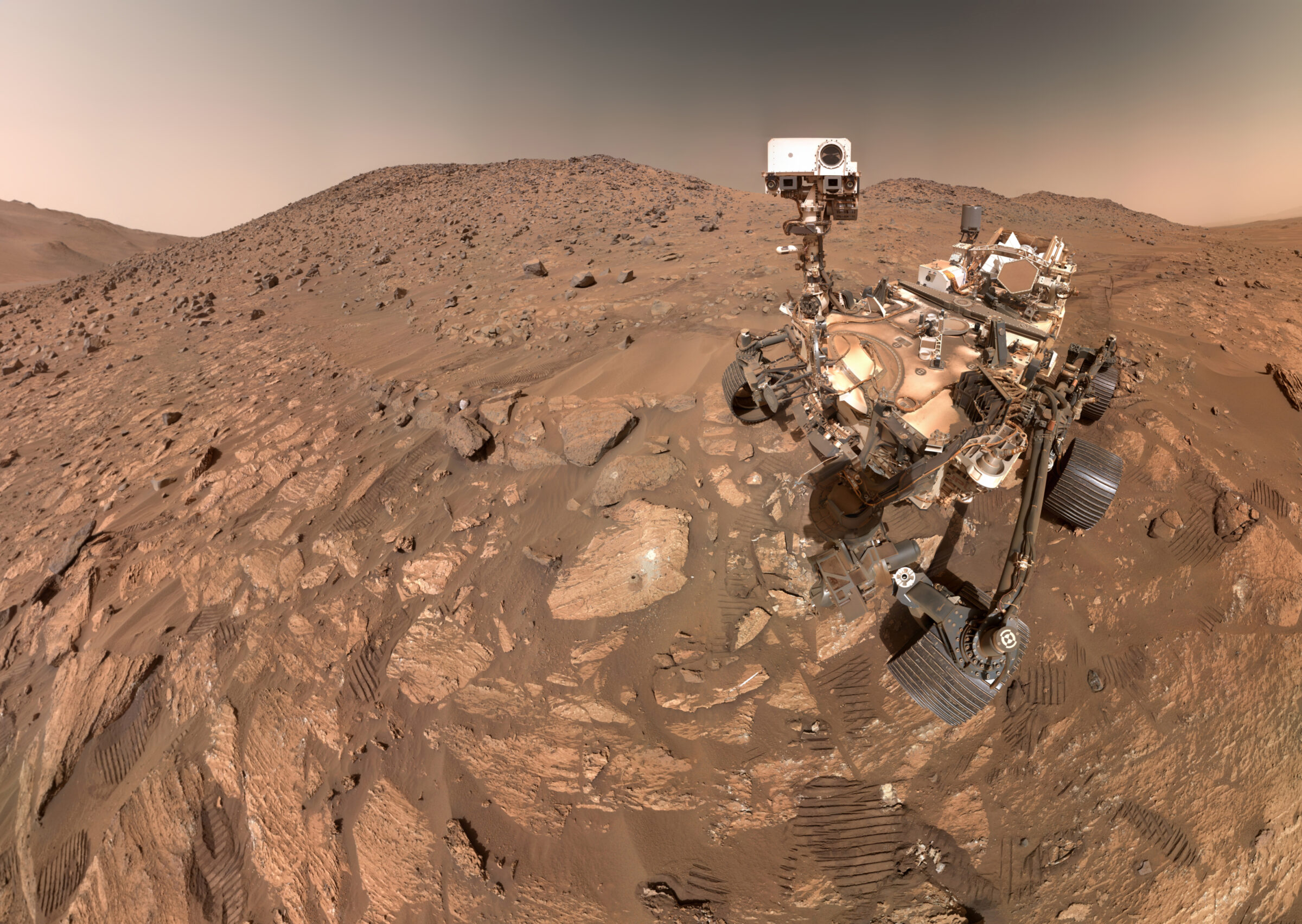

NASA has found what may be the closest thing to an ancient habitat ever seen on Mars. The site — a single 3.5 billion-year-old rock — shows signs of all the conditions life needs to thrive. Though more research needs to be done, it’s possible that ancient microbes could have left a mark there that remain visible to this day.

The discovery

On July 21, NASA’s Perseverance rover spotted a strange rock partially buried in a dry riverbed. White streaks hinted water once flowed through the stone, and Perseverance also found signs of organic molecules, the building blocks of life. But what really stood out was a smattering of black and white spots along the rock’s surface. On Earth, such “leopard spots” are mainly known to form in two ways: from microbes, or through chemical reactions that can provide fuel for life.

It is too soon to say just what that means. At the very least, scientists have now discovered a single place on Mars with signs of once hosting all three of life’s main ingredients: liquid water, energy, and organic molecules.

“This is exactly the kind of rock that you’d pick up if you were looking for life on ancient Earth,” says Bethany Ehlmann, professor of planetary science at the California Institute of Technology and president of The Planetary Society. “That’s why it’s so exciting.”

Scientists, who have named the rock “Cheyava Falls,” are still working to understand its history, detailed chemical makeup, and the timing of its potential habitability. Investigating any potential signs of past life will be a long, complicated process.

“There’s so many ways these things can form,” says Luther Beegle, scientist and former principal investigator of Perseverance’s SHERLOC instrument.

Even on Earth, he says, it can be difficult to figure out when something is related to life or not — and that’s with a broad understanding of how life works on our planet. We don’t have that same knowledge about Mars, so potential signs of life there are even harder to untangle.

“Until there’s more data,” Beegle concludes, “there’s no way to tell.”

Bringing Cheyava Falls back to Earth

That’s where Mars Sample Return comes in. The joint NASA/ESA mission, though currently being restructured following budget cuts, is intended to follow up on Perseverance’s most intriguing discoveries by taking them back to Earth. The rover has already collected dozens of samples along its journey. Now, Perseverance also carries a piece of Cheyava Falls that could shed light on its potential to have hosted life.

“It’s exactly why we have to bring the rocks back,” says Ehlmann. “You want to get it into the lab. You want to slice it open.”

Perseverance can only do so much with the instruments it carries, but back on Earth, scientists could study Cheyava Falls with their largest, most powerful tools. They could learn more about what’s in the rock, how it formed, and its history on the surface of Mars.

Cheyava Falls is far from the only intriguing thing that Mars Sample Return would bring back, either. Each specimen from Mars would have the potential to tell us more about the others, and together the collection would paint a broader picture of the planet’s past.

A discovery, no matter what

If researchers end up finding that no part of Cheyava Falls was produced by microbes, the discovery would still expand what we know about life on Mars. Since the rock’s organic compounds would have formed on their own, scientists would be able to study how that happened to get a better sense of the possible ingredients for ancient Martian life.

“Even if it’s ‘just’ a building block of life, a building block of life is pretty darn exciting, too,” Ehlmann explains.

Cheyava Falls could also tell us about life’s chances of survival on ancient Mars. Scientists have wondered whether rocks with hydrated sulfates — the source of Cheyava’s white streaks — might have once offered a resilient habitat for alien life. As the surface of Mars began to dry out billions of years ago, microbes could have survived in these rocks by extracting the water within. Combine that with the source of energy behind its leopard spots, and a place like Cheyava Falls may have acted as one of the last habitable environments on a fast-changing Mars.

The long road to Cheyava

Though no one has ever seen anything like Cheyava Falls on Mars before, the discovery did not come completely out of the blue. It represents years of painstaking NASA strategy.

“This is why they went here,” says Bruce Betts, chief scientist for The Planetary Society and LightSail program manager. “This is what Perseverance was sent to do.”

NASA selected the rover’s landing site, Jezero Crater, in part because of its potential for discoveries like this. The river valley where Cheyava Falls sits once flowed with water billions of years ago, emptying into a lake within Jezero Crater. Perseverance provides a window into this past as it explores the area. The rover has found other intriguing samples that are shaping our sense of whether Mars could have once supported life.

Though NASA’s grand plan for Mars appears to be paying off, its next step is unclear. Mars Sample Return aims to bring back samples by the early 2030s, but that timing is in flux while NASA redesigns the mission amid indiscriminate budget cuts to its science programs. That could affect when scientists can finally get to the bottom of what’s going on at Cheyava Falls.

“Odds are, unless they find something more concrete, like little creatures waving at them,” says Betts, “it’s going to be a few years.”

In the meanwhile, Cheyava Falls stands as an example of what we have to gain by doing space science. The discovery marks a culmination of years of careful planning, but is also the first of its kind. It opens new possibilities and questions in the search for life in the Universe.

“That’s why we explore,” Betts says. “We don’t know what we’ll find.”

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth