Why this Ceres mission could change the search for alien life

Written by

Jamie Carter

Science journalist

July 7, 2022

Could there be primitive life forms on the closest ocean world to Earth? We could know more by about 2044 after the recent National Academies Planetary Science Decadal Survey recommended NASA send an exciting sample return robotic mission to the surface of dwarf planet Ceres.

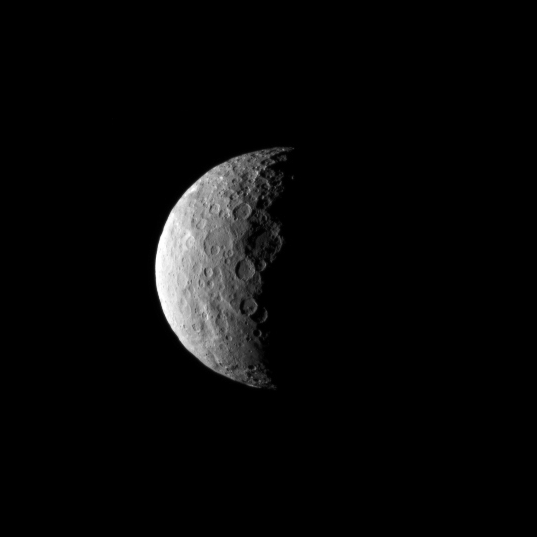

At less than a third of the Moon’s diameter at 476 kilometers (296 miles), the tiny rocky world has consistently defied classification by astronomers and planetary scientists. When it was discovered in 1801 by Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi, Ceres was initially thought to be a comet, then a theorized “missing planet” between Mars and Jupiter. In the 1860s, astronomers realized Ceres was merely the biggest object in an asteroid belt and it was relegated to the status of minor planet. In 2006 it was reclassified once again as a dwarf planet along with distant Pluto.

Ceres has recently been promoted to one of the most intriguing classifications of all — an ocean world.

“Ceres has a crust of about 25 miles of water-rich material and about 40% of its volume could be water,” said Dr. Julie Castillo-Rogez, a research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, deputy principal investigator on the Dawn mission, and co-author of Ceres: An Ice-Rich World in the Inner Solar System. “What’s really exciting is that it has a lot of carbonates, it has ammonia on its surface, it has brines and we think a lot of organics on its surface.”

This tiny world orbiting the Sun about 414 million kilometers out (257 million miles) is now considered something of a chemical factory, a bona fide target for astrobiologists hunting for life beyond Earth. As a bonus, it’s much easier to reach than ocean moons in the outer Solar System such as Europa at Jupiter and Enceladus at Saturn.

Cue the Ceres Sample Return mission concept, which is now being recommended as a priority for NASA’s New Frontiers program. If all goes as planned, it will bring organic material from another ocean world back to Earth for the very first time.

What NASA’s Dawn mission discovered

Ceres was little more than a blurry dot until 2015 when NASA’s Dawn mission orbited, photographed, and mapped it through 2018. Dawn changed everything we knew about Ceres — the inner Solar System’s only dwarf planet is now not only thought to be the second-wettest world after Earth, but possibly geologically active and potentially hospitable to life.

Dawn confirmed that Ceres has a subsurface ocean and also made surprising discoveries at the bottom of a large crater called Occator.

“There are these very bright regions that are evidence of sodium carbonates — compounds of sodium, carbon, and oxygen — also found on Enceladus, which is a marker of a habitable environment,” said Castillo-Rogez. These bright spots may be salts left behind by the evaporation of salty water that seeps up from an underground reservoir or ocean.

Dawn’s spectrometer team also found that salty water is probably still seeping onto its surface at a 14-kilometer-wide (9-mile-wide) region called Cerealia Facula ("facula" means bright area).

In short, Ceres has — or had — puddles.

Dawn is dead. It ran out of propellant in November 2018 and will silently orbit Ceres for the next 50 or so years. But a more ambitious successor could theoretically sample those bright spots and bring them back to Earth.

Fetching a piece of Ceres

The mission concept study submitted to the most recent Decadal Survey wants to send a spacecraft to monitor Ceres for geological activity, determine the depth of liquid water below Occator crater, and send a lander to a bright spot called Vinalia Faculae to take a 100 gram sample.

Why not Cerealia Facula? “We don’t want to go to where the liquid is being exposed at Cerealia Facula because there are planetary protection issues," said Castillo-Rogez, referring to a set of internationally agreed-upon rules that prevent cross-contamination between Earth microbes and those that might exist on other worlds. Vinalia Faculae, where the mission team thinks liquid from the deep interior may have been exposed through a fracture, could provide valuable samples with less potential for cross-contamination.

The mission is designed to come in under the $1.1 billion cost cap of NASA’s New Frontiers missions, partly by using the same sample return tech now being developed for Japan's Martian Moons eXploration mission to return a sample from one of Mars' moons, Phobos.

“The proximity and the low gravity make it so we can do a sample return at a relatively low cost,” said Castillo-Rogez.

According to the concept a spacecraft would launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket (or similar) in December 2030 and arrive at Ceres in July 2037. After 18 months in orbit for detailed reconnaissance it would send a lander to collect samples, “hop” to a second location elsewhere in Occator Crater to collect more samples, then launch back to Earth to arrive in 2044.

How exciting will the samples returned to Earth be? “We think there will be organics in the salts,” said Castillo-Rogez. “It’s very common on Earth.”

Samples returned from Ceres could also help write a new chapter about the early history of the Solar System. That’s partly because Ceres is in the wrong place.

Ceres as a time capsule

Ceres makes up about a third of the mass of the entire asteroid belt. Its surface is a mix of water ice, carbonates, chlorides, and clays. It has no atmosphere, but it does have a mist created by sunlight evaporating the ammonia and water ice below its surface. Ceres is unique and almost certainly not from the asteroid belt originally.

It could be from the outer Solar System, according to the authors of a paper published in the journal Icarus in May 2022.

“Ceres began forming in an orbit well beyond Saturn where ammonia was abundant [and] pulled into the asteroid belt as a migrant from the outer Solar System,” said co-author Rafael Ribeiro de Sousa, a professor in the program of graduate studies in physics at São Paulo State University, Brazil.

The study’s main finding was that in the past there were at least 3,600 Ceres-like objects beyond Saturn’s orbit. “With this number of objects, our model showed that one of them could have been transported and captured in the asteroid belt, in an orbit very similar to Ceres’ current orbit,” said Ribeiro de Sousa.

Is Ceres a rare remnant from the birth of the Solar System 4.5 billion years ago? It could be — and it could also be a surviving member of a group of protoplanets that transported water and organic material from the distant Kuiper Belt to the inner Solar System, including to Earth. It’s a rare opportunity to study the early Solar System — and its proximity and low gravity makes it a relatively low-cost mission.

“Ceres is a very intriguing object,” says Castillo-Rogez. “We really want to know more about what’s going on.”

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth