Planetary Radio • Jul 23, 2025

New Horizons: Celebrating a decade since the Pluto flyby

On This Episode

Alan Stern

New Horizons Principal Investigator

Adeene Denton

NASA Postdoctoral Program Fellow at the Southwest Research Institute

Jack Kiraly

Director of Government Relations for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

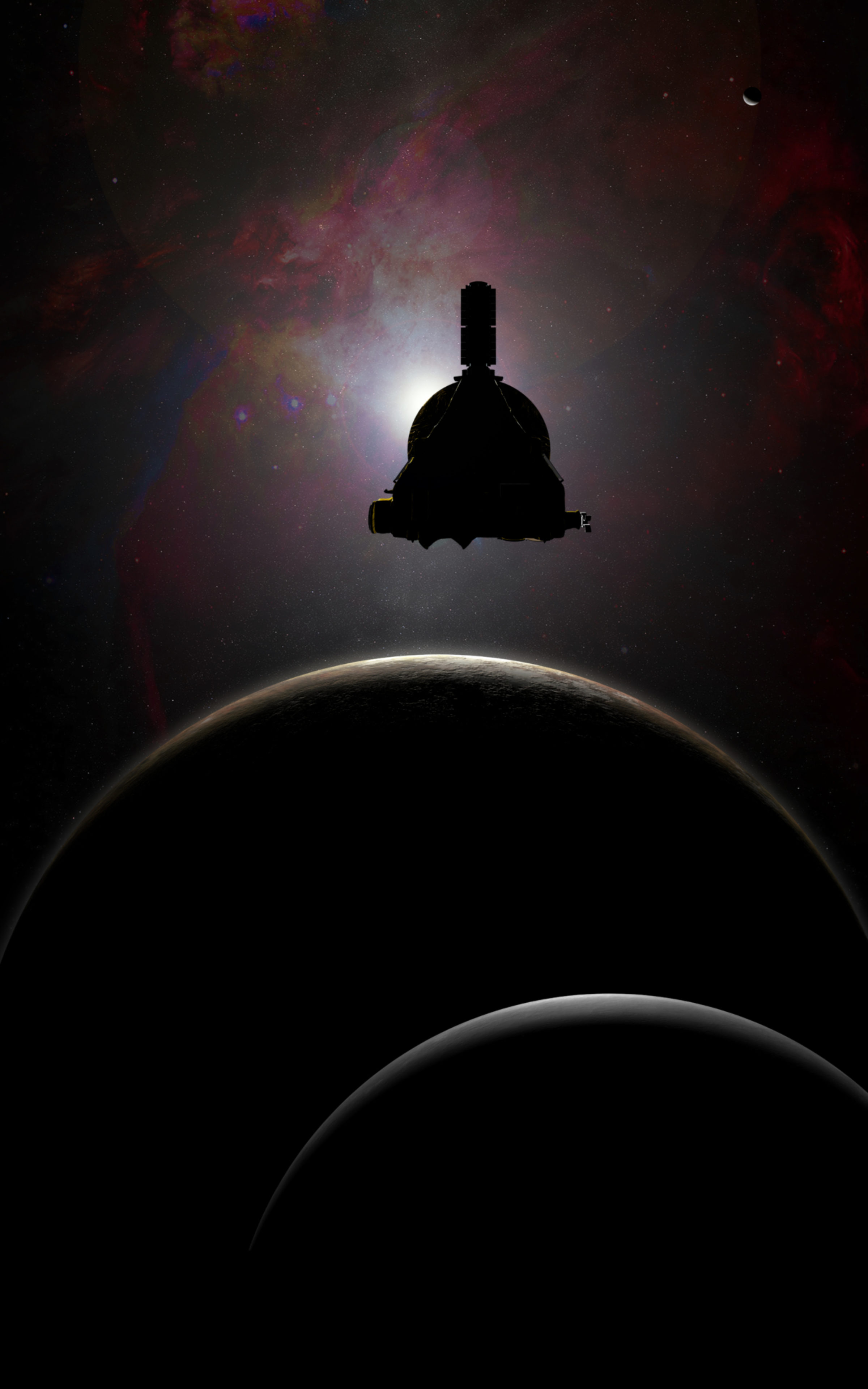

On July 14, 2015, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft made its historic flyby of Pluto, transforming our understanding of this distant world. Ten years later, we’re celebrating that iconic moment and the mission that made it possible.

We begin with Alan Stern, principal investigator of the New Horizons mission, who reflects on the mission’s origins, its most surprising discoveries, and what comes next as New Horizons continues its journey through the Kuiper Belt.

Then we check in with Adeene Denton, NASA postdoctoral program fellow at the Southwest Research Institute, who just returned from the “Progress in Understanding the Pluto System: 10 Years After Flyby” conference held at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Adeene shares highlights from the event, which brought together scientists to explore new results from New Horizons, JWST, Hubble, and ground-based observatories on Pluto, Charon, and the broader Kuiper Belt.

Finally, Planetary Society Director of Government Relations Jack Kiraly joins us with a major update on the ongoing fight to protect NASA science from devastating budget cuts.

And don’t miss What’s Up with our Chief Scientist, Bruce Betts. We’re talking Arrokoth, the most distant Kuiper Belt object New Horizons visited after Pluto.

Related Links

- Pluto, the Kuiper Belt’s most famous dwarf planet

- New Horizons | JHUAPL

- New Horizons, exploring Pluto and the Kuiper Belt

- The Pluto Campaign

- Ten years after Pluto, New Horizons faces a new threat

- Progress in Understanding the Pluto System: 10 Years After Flyby

- 2016 Cosmos Award Honoree Alan Stern and the New Horizons team

- Planetary Radio: To Pluto and Beyond with Alan Stern

- Planetary Radio: Alan Stern and a Triumph at Pluto

- Planetary Radio: Alan Stern and the Rise of Pluto

- Planetary Radio: Alan Stern Puts His Stamp On Pluto

- Planetary Radio: Pluto Amazes!

- Planetary Radio: Kiss-and-capture: The dance of Pluto and Charon

- Planetary Radio: Splat or subsurface ocean? The mysterious positioning of Pluto’s heart

- Pluto: The Discovery of a Planet

- Pluto is not the end

- Moohoodles Twitch stream: New Horizons Pluto Flyby 10yr Anniversary

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We are celebrating the ten-year anniversary of the New Horizons flyby of Pluto, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. A decade ago, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew past Pluto and revealed a world that was far more dynamic and surprising than anyone had imagined. This week we're looking back and forward with Alan Stern, the principal investigator behind the mission. Then we'll check in with Adeene Denton, NASA postdoctoral program fellow at the Southwest Research Institute.

She's fresh from the anniversary conference at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab. We'll hear all about the fresh science that's still coming out of that data. Our own Jack Kiraly, director of government relations at The Planetary Society joins us with an update on the latest space advocacy developments. Good news everyone, but also much work still to do. We'll let you know how you can help protect missions like New Horizons from premature shutdown. And finally, we'll close out with what's up with Bruce Betts, our chief scientist.

As we talk a little bit about Arrokoth, the furthest object in our solar system that we've ever observed up close. Thanks to New Horizons. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed. About the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and are placed within it. Also, I want to send a huge thank you to all of the space fans who joined Twitch Streamer, Moohoodles and me for our Pluto flyby anniversary live stream.

We had an amazing time celebrating this historic mission and raising funds to support space advocacy. If you missed it or you just want to relive the moment, I'll be posting the YouTube link for that on this episode page at planetary.org/radio. And to everyone who donated during the stream, thank you. Your generosity fuels our Save NASA science campaign, which is helping to protect missions like New Horizons and keep the spirit of exploration alive in the United States. It took nearly 20 years of relentless advocacy to make it happen, but on January 19th, 2006, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft launched on a mission to explore the outer solar system.

Nearly a decade later on July 14th, 2015, it made a historic Pluto flyby, revealing a world that was far more geologically active and beautiful than I could have ever imagined. New Horizons gave us the first close up view of a world that had remained a pixel in our imaginations ever since it had been discovered, and it changed planetary science forever. The story of New Horizons is also a tale of perseverance and public support. The Planetary Society and its members fought to keep that mission alive through years of cancellations and near misses.

That long effort paid off in a spectacular fashion, and we were so proud to honor the New Horizons team with the Cosmos Award for Outstanding Public presentation of science shortly after that Pluto flyby. To learn more about the journey behind the mission, I highly recommend the book Chasing New Horizons, which was written by Alan Stern and Astrobiologist David Grinspoon. It's a behind the scenes look at one of the most ambitious planetary missions ever attempted. Dr. Alan Stern has led the New Horizons mission from the very beginning, and continues to guide its journey through the Kuiper Belts to this day.

He's a planetary scientist, commercial space traveler, former head of NASA's Science Mission directorate and associate vice president at the Southwest Research Institute. Alan is one of the most vocal champions of exploration at the edge of our solar system and personally, I've been hoping to get a chance to speak with him for years. Hey, Alan.

Alan Stern: Hey Sarah. How are you doing?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Doing really well, and thank you so much for joining us to mark this anniversary moment.

Alan Stern: This is so great. Thank you for having me on.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I also have to pass along a hi from Mat Kaplan, the previous host of the show. He was so excited to hear that you were going to be back on the show to talk about this.

Alan Stern: Please pass a hi back if you don't mind being a middle person in that. That's so great.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So it's been 10 years since the New Horizons mission flew by Pluto and its moons. When you think back to that moment in your life, what really stands out to you most now?

Alan Stern:

I have a couple of top thoughts that come right to mind. The first is just the amazing feeling of accomplishment of our team. It was really quite an underdog mission, in a lot of ways and people poured their lives into it for a very long time. And it all worked. It works just spectacularly. And the second thing to me was how beyond all scientific expectations, Pluto performed. And I used to say this even 10 years ago. It's like the solar system saved the best for last. And those two things are probably tops, but there was also this amazing resonance with a public.

And through the press and social media and just people, just thousands of them, the same way that with the Voyagers, they'd all show up at JPL. They all came to our flyby. It was like a Woodstock for nerds.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It really was though. At the time, I was working at Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles. And when I tell you it was like Pluto-palooza for months, I'm not exaggerating. People were literally learning how to give talks about Pluto in other languages because people were flocking to the observatory to talk about it.

Alan Stern: Yeah, I don't doubt that. We had a lot of ... We had hundreds of press show up at the flyby and many of them were from Asia and Europe and other far away places.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What did it actually feel like to see Pluto up close for the first time, especially after all these decades of effort that it took to get there?

Alan Stern: Well, it was really gratifying on a personal level, because we worked ... It's just a dot and a distance until you get there, and then it just turned out to be ... We were using an old saying, than the bell of the ball, just the star of the show that maybe that's a better way to say it. It was so magnetic, a personality, the geology and the atmosphere and the whole just ambiance of Pluto and so many people had said, you're going to get there. It's going to be this boring ice ball. And we're like, "No, no. We have some pretty good indications from crude, from a light curve, from the composition, from the atmosphere that we're already seeing." This is going to be an interesting place, but it way outperformed our expectations. I think we had Sarah, the whole ton of predictions that the team had made and we'd had a poll within the team, things we'd find. And if any one or two of these things turn out, it's going to be Blockbuster. And then we'd have eight of them. They're all in the same planet. They're all there. It's stunning.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really though those images blew my mind, like I had expectations that it was going to be really cool to see a new world that we'd never really seen before up close, but when you actually look at that thing, it was so surprising. So beyond what I expected.

Alan Stern:

Well, over performances, it tends to be Pluto's game. I can remember at the beginning of my career when we were doing really crude things, like the first pictures with Hubble in the late 90s were like, well, that's a lot spottier than a normal thing at this resolution. You look across the outer solar system at solid bodies and even things considerably larger than Pluto, like moons of Jupiter, that's like Pluto is turning out to be a lot more complicated even at low resolution and the same with its atmosphere.

And so, we had some expectation, but what you're saying is spot-on, it really ... I think it blew everybody away. I don't think anybody was like, "I'm disappointed. Pluto wasn't enough." There was none of that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Were there tears or emotional reactions from the team when they finally saw those images?

Alan Stern:

Lots of emotional reactions and I don't remember too many tears. There probably were some. What I do remember is a lot of hugs. Just people feeling like they wanted to hug each other. When we hired people to come on the proposal team in 2001, and we were in a competition, not just for funding, but even to just win the right, to be the team that would get the design and build it and fly it. We asked people specifically for a commitment that they would stay with it all the way to Pluto. They wouldn't just come on to launch.

And I'm talking about engineers, mission operations people, not just science team. Science team always stays because they're in it for what happens at the end. But we asked the whole team that we told people when we hired people, you're going to come on this mission in your 20s, your 30s, and it's a 20-year commitment between building and flying and everything. And you can go work on other things, but we want you to stay on New Horizon and you have to commit to that.

And they did, with very rare exception, a couple of people who had other things that got in the way and a couple of people passed away, which was sad. But it was really the same people and our kids had grown up and time had gone by. I'm sure it felt the same on Voyager, but Voyager had a much bigger budget and it was really a centerpiece mission for NASA in those days. New Horizons was much more of a low budget underground of people who just worked and toiled from 2001 to 2015, just to see how this would turn out.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How many people are still working on the team?

Alan Stern: A lot of them, surprisingly 10 years later, we're on our fourth project manager and she literally was a grade schooler when we wrote the proposal. The science team and the mission operations team and the engineering team are largely intact. There've been some retirements. We brought in some new younger people as you should for a lot of reasons, but in the core team, virtually everybody is there.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, we're actually just a few days out from this anniversary as we're speaking. Are you guys all going to get together and do some kind of party or something to celebrate this moment?

Alan Stern:

Well, not really a party. There are going to be celebrations, but the thing is, a few years ago the opportunity came up to do a major scientific conference on what we've learned from the time of 2015 when New Horizons revolutionized everything about Pluto and its system of moons. And to also look at all the new things that we'd learned from the James Webb, from the Hubble, from ground-based, from computer modeling, even theory. And to put it all in context with what we've learned about other dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt ... So when that got cemented as a conference through the Lunar and Planetary Institute, the obvious thing to do was to see if we could have it in July of 2025.

And then also, as a bonus, not as a core part of the science meeting, but as a bonus to have it in the same place at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab where the flyby events were, and we ended up with literally the same week, 10 years later. So that's an opportunity for those who can come and be there to reminisce and also to celebrate the accomplishment. So I'm pretty sure there's not a big party, but there are some celebratory evening events. People will get to tell stories and see pictures of the time of the flyby and just see up friends and talk.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Adeene Denton who's been studying Pluto using all the results from New Horizons who I know is going to be at this conference, she was speaking about it a few months ago, which is so absolutely excited to go there and share everything that people have been learning about Charon's formation or Charon, depending on how you like to pronounce it, or the potential for a subsurface ocean, just all these years later, this data is still teaching us so much about this world.

Alan Stern:

It's true, and it takes a while. It took us 16 months just to get the data all to the ground. That's part of the way the spacecraft is designed for a mission with very long distance between the Earth and Pluto. So the data rates were low, but there was a lot of skim the cream stuff early, but a lot of stuff, it just takes a while to see the connections between it for people to do the hard work of data analysis, careful work, the computer modeling behind it.

And then as new things started to come in from ground-based observatories, the Hubble, Webb, it got just deeper and richer. And take a person, Adeene who's spectacular. I was on her PhD committee and on a couple of papers when she was doing her PhD rather, and she has done really important work, but she wasn't even in grad school when we had the flyby.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know. Isn't that amazing? The fact that this mission has been going on for so long that you can bring in whole new generations of scientists, it's just absolutely amazing.

Alan Stern: Well, we always said to people, this one is about delayed gratification because we built it in almost record time. We only had four years and two months from U1 to U-launch and most missions are eight, 10, sometimes 12 years to get to Launch Pad. And then, we were 10 years crossing the solar system and we didn't pass anything along the way, but Jupiter shortly after launch, and so you add that up and it is just a lot of delayed gratification. A lot of missions don't have to do that if you're ... I've been on lunar missions and Mars missions where you're there almost before you know it after launch.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We spoke a little bit about this earlier, but what were some of your experiences with the public reaction to this flyby?

Alan Stern:

There's so many ... It's just like a kaleidoscope to me, some of the most moving ... That was very moving to me that the worldwide response, I remember saying in a public talk that was broadcast shortly after the flyby that we had been on the front page of over 450 newspapers above the fold on the morning after the flyby on six continents, and I got an email the next day from the editor of the only paper in Antarctica. And he said, "Don't forget about us." And he had a copy of his newspaper. That was just so cool.

But we also ... We literally, I would go and get public talks and I'll give you just one example. I remember a mother coming to me in a line of people just to talk after I gave a presentation and she said, I have to tell you a story. She said, "Alan, my son was a slacker and a failure, a teenage son. He watched your flyby." And she started crying. She couldn't even finish the sentence. She said, "He watched your flyby and said, I want to do that. That's what I want to grow up and be, is in that line of work. And it's two years later, he's a straight A student. You saved my son."

She didn't mean me. She meant New Horizons and that flyby. You saved my son. I nearly started crying. It was amazing when you hear something like that because as scientists, when you work to build a mission and you think of the science that's coming out of it, you never think it's going to have that kind of an impact on human beings. And I'll never forget her telling me that story.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You're making me emotional thinking about it. I mean, honestly, I think that's what's so special about space science as a field. It has this power to motivate people to see their deepest, most brightest selves in the future because it's so aspirational.

Alan Stern: The one thing about space flight is that it's never done by a single individual. It's only done by teams of humans that together can do something, that no one of us could accomplish. That's just so cool to me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think too that a lot of people may not realize how close New Horizons came to never flying at all. Can you share a little bit about the advocacy that helped get this mission off the ground and what it meant to you in the team to have that kind of public support?

Alan Stern:

Yeah, I'd love to talk about that because as backstory, and a lot of people may not remember or even have ever known that the scientific community pushed to have a mission at Pluto for 17 years before it got funded, and it started in the late 80s and it really got funded in the early two thousands. And there were so many reversals of fortune and missions that were started but canceled or never got out of the study phase or made a mistake and got out of control on cost and so forth.

And it just went on and on and on, until we finally had an opportunity called New Horizons, where it actually all, not just got to the launch pad, but got the goods of Pluto and The Planetary Society was with us from the start, even in the early days when Luke Friedman and Carl Sagan and Bruce Murray were all still in their prime, they were helpful and Bill Nye was helpful. In fact, we put him in our proposal, he agreed to it, and this was 2001 and we called him Bill Nye, the Pluto guy, was going to be a part of our public outreach team.

You guys played a huge role in making it happen, delivering I think at one point, 10,000 letters, hard copy letters in the days that people sent letters in, with a postage stamp delivering them to Congress. And there was of course advocacy from lots of other groups. There were no decade of surveys back then, so it was much more kind of make it up as you go, advocacy. But so many people contributed to this and wanted to see it happen in the space community, the science community, public policy community. Could have never done it without all those people because there were so many nos.

Well, we wanted to, but we can't, and now we're canceling it or something would come up and all that advocacy, I remember very importantly, there was a boy, a teenage boy who drove to NASA headquarters and literally knocked on the front that worked at NASA headquarters in 2000, when the whole thing had been canceled before there was a New Horizons, it was called I think Pluto Corporate Express. And this young man just came into NASA course, how do I find whoever's in charge of science? And he was literally in high school, literally a minor, literally a kid from Pennsylvania that got in his parents' car and drove.

And some of the bureaucracy people put him in a room, something you could never do today, you have to be considered offensive, but they put him in a room and sort of grill them, and said, "Who put you up to this? Who paid for your travel?" And he's like, nobody put me up to this. I read about this in the newspaper and I'm for doing this, and I paid for my gas. His name's Ted Nichols, and he became a poster person for why the Public really had a stake in this. And there are a lot of other stories, but that's a particularly good one about the advocacy.

Because it matters when people get behind things. So for all of you who are listening, when you want to see something happen, some future mission, don't forget to get behind it publicly because it is, in the way we do things today, done through a federal government agency and we're all maybe not owners, but certainly stakeholders in it as American citizens.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Now, it was worth all of that advocacy. I mean, I remember being a child flipping through my solar system books with all these beautiful Voyager images of these other worlds, and then just getting to Pluto and having this vague idea of what it looked like from this beautiful artwork that people drew, but to be able to complete that catalog and to give people this mental image of this world, but not just what it looked like, just how surprising it was. I'm so glad that people spent that time to advocate for it because it was so worth it.

Alan Stern:

It really was. And you're like a lot of people, myself included, that Pluto was unfinished business. The last of the classical planets, and because of some scientific decisions, Voyager couldn't get there. Just from a trajectory standpoint, the decision was that it never was built to go that far. And so to concentrate on Jupiter and Saturn science and the trajectory that resulted, couldn't get Voyager to Pluto. So it fell to my generation, the generation after Voyager to pick that ball up. And really, the flyby of Pluto in 2015 was the first time we've been to a new planet since the late 80s with Voyager 2 and Neptune.

And we once calculated, 40% of the people alive in 2015 were either not born or too young to remember the last time there had been a first mission to a new planet and it just turned out to be usually popular because it was like an adventure story happening in real time, day by day, as we got closer and closer. And then, once we actually had the really high resolution stuff from flyby day and that started to come to the ground, over a period of about a year, New Horizons just kept sending spectacular image after image after image and discoveries about Pluto, its moons and its atmosphere, its interior.

Possible, probably, probably Adeene would tell you, ocean under its ... what liquid water ocean and everything else about it, that's just so spectacular. So by the way, here's a plug for a future generation. We need to send an orbiter and go back.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But really though there are so many mysteries left unanswered at this point.

Alan Stern:

And it takes an orbiter. That's what we do. The first missions to Mars were flybys. It turned out to be mouthwatering, and we sent orbiters. They showed us even more ... that that was the case and we just wanted more and more. Sometimes people say to me now, an orbiter is just too high a hill to climb. It's going to cost a lot more than New Horizons and it's a much bigger scale enterprise, and that's all true. My response to that was, well then, let's put it in perspective and start a movement for a human mission to Pluto. And of course, by comparison, the orbiter will look like a cinch.

So then instead of looking at it as big and complicated compared to new Horizons, it'll look small and trivial compared to a human mission to Pluto.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What would you say were some of the most surprising discoveries we made there and what are you still really curious to find out about a decade later?

Alan Stern:

Well, I think the biggest single thing was the complexity, was so far beyond what we expected. Generally, there's a rule of thumb that smaller worlds are less complex and there are a number of geophysical reasons for that. The second big discovery was Pluto is active and so many small worlds are dead. Even the moon, which is somewhat larger than Pluto. Our Moon Luna, the Earth's moon is larger than Pluto, but its geology, its engine largely ran out a billion years after formation. There was some activity in the second billion years.

But we're now four and a half billion years downstream, and you have to really look close to see much going on in the moon, no detriment. I consider myself a lunar scientist, but in general, the only worlds that show intense activity that are small are the ones that get external sources of energy, like Ion is pumped up by the other Jovian moons and a gravitational tug with the planet being the host. And Pluto we knew would be a kind of acid test, could you have a small world that's active? It's out there isolated in the middle of nowhere.

And it turned out to be not just active but crazy active. The biggest single feature on the planet is a glacier that's overturning due to convection in the ice. And it's a scale of Texas and Oklahoma combined, and we know it has no craters on it and we can therefore determine it was born yesterday geologically. And no one really understands how a world the size of Pluto can make things the size of Texas yesterday. And then on top of it, we see evidence for avalanches and atmospheric change and meteorological or volatile transport.

That all indicate different forms of activity on Pluto, and then the atmosphere blew us away, and the moon is the largest tectonic belt in the solar system. Charon's weird, dark red polar cap that doesn't look like any other polar cap in the solar system. There just were so many things about Pluto and its satellites that were blockbuster headlines, including multiple lines of evidence for this Europa like interior water, ocean that could even have astrobiological potential that Pluto just delivered and delivered and delivered.

These major headlines, which I think tell us as we go out into the Kuiper Belt to study the other dwarf planets there, Eris and Sedna and Orcus, Makemake, and Ixion but we're going to see a lot more surprises just like we did as we compared the terrestrial planets and the early days of space exploration.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's so much we could learn with a return mission, especially in orbiter. I want to know what's going on with that rich trough system and whether or not there are potential remnants of the situation that created this kind of ... I mean I almost think of it as a binary dwarf planet. We think of Pluto as this object all on its own, but its relationship with Charon is so fascinating, that there's just so much left that we'd need to know about this.

Alan Stern: 100%, let's go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Let's go. But then, immediately after going on this beautiful adventure through Pluto and blowing our minds about this, you took this mission and went on another object, this second target, Arrokoth, how did you figure out where this thing was going to be going while this mission was already en route?

Alan Stern:

Yeah, we discovered it in 2014, when the mission was architected by advisory committees in the late 90s and early two 2000s. We already knew about the Kuiper Belt, and when NASA asked for proposals, they said, if you're writing a proposal for this mission, your spacecraft has to be designed and capable of going past Pluto out into the Kuiper Belt, making as many flybys as you can out there and being able to transmit the data back from the larger distances of the Kuiper Belt and have the power to keep going out there and the fuel to do all this. And that's what we proposed with New Horizons, so did our competitors.

But our proposal was the one NASA chose. And so, we knew we would be doing this. If everything was working well, we would go on past Pluto, but we didn't know enough back at the time. We wrote the proposal, we even launched the spacecraft to find a target along our path. We had to wait as the ground-based technology got better and also Hubble got better instruments. And then in 2014, we got a big bunch of time from the space telescope, Hubble Space Telescope, to look for this target, and we actually found three targets that we could reach right away in a matter of a week.

All three were spotted and we chose Arrokoth in part because it was the easiest to reach and it would leave the most fuel for maybe a third of flyby, Pluto, Arrokoth and then one more. And then we just tracked it from the ground and tracked it from Hubble and computed the intercept course. We had the advantage of Hubble being so accurate that we could actually do ground based occultation, that gave us even higher accuracy. And so, we just hunted it down in the darkness of the Kuiper Belt and had another spectacular flyby that also revolutionized scientific knowledge.

But this time not about a planet, but a seed or a building block of the planets out there. So it told us a lot about the origin story of how Pluto and its kin, the other dwarf planets and even how larger planets like the Earth and Mars, maybe even the gas giants even, started. And it really taught us a great deal that we did not know before that the original accretion of the planets ... It started with this gentle accretion of small bodies that are only tens of kilometers across. And we could not know that from any other mission before because the Kuiper Belt is a much better time capsule.

Being much colder and much less collisionally active than the asteroid belt. This was the first really pristine object that we could see, that we knew was not modified by much of anything. So that was a big accomplishment for our team, and of course scientifically, really a goldmine in terms of learning about planetary origins. And that's why we want to go on if we're able to, and have another corporate belt object flyby in the future where the space could be much farther out and the conditions might be very different.

And so we want to compare formation in the inner corporate belt where Arrokoth was a flyby that would give us the same kind of information in the outer corporate belt twice as far away from the sun.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Plus in the interim, we've had new instruments and observatories come online with things like JWST and now this new Vera Rubin Observatory. I'm sure, it would be even easier to find targets out there that might be able to work for that.

Alan Stern:

Well, if Vera Rubin gets pressed into that search, it'll do better than anything else on the ground. It's just a better tool. We know that, just from its technical specs, that it can do literally almost an order of magnitude better in searching than the best ground-based tool, which is the Subaru, the Japanese giant telescope in Hawaii, which has done great, but it can only go so far with its instrumentation, and Vera Rubin is just much more modern and has instruments that are more optimized to things like this kind of needle in a haystack search.

And even better than Vera Rubin when NASA launches the Nancy Roman Space Telescope, which is still planned, that will do even better, and that may be the ... It's probably the best tool that we'll have before we leave the Kuiper Belt to find a new flyby target. So we're going to press all those into service if we're able to.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of our celebration of the New Horizons Pluto flyby ten-year anniversary after the short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Planetary Defenders, Bill Nye here. At The Planetary Society, we work to prevent the earth from getting hit with an asteroid or comet, such an impact would have devastating effects, but we can keep it from happening.

Bruce Betts: The Planetary Society supports near-Earth object research through our Shoemaker NEO grants. These grants provide funding for astronomers around the world to upgrade their observational facilities. Right now, there are astronomers out there, finding, tracking and characterizing potentially dangerous asteroids. Our grant winners really make a difference by providing lots of observations of the asteroid so we can figure out if it's going to hit Earth.

Bill Nye: Asteroids big enough to destroy entire cities still go completely undetected, which is why the work that these astronomers are doing is so critical. Your support could directly prevent us from getting hit with an asteroid. Right now, your gift in support of our grant program will be matched dollar for dollar up to $25,000.

Bruce Betts: Go to planetary.org/neo to make your gift today.

Bill Nye: With your support working together, we can save the world. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's still a lot of opportunity for science out there because New Horizons is the only functioning spacecraft that's in that section, that outer part of the heliosphere. And it has all these instruments on it that Voyager didn't have at the time. What do you think it's uniquely positioned to teach us about that place in space?

Alan Stern:

Well, that's a good point. A lot of things, actually, for one thing, New Horizons is ... And most people don't know this because it's not headline making, but it's scientifically important. We've now studied almost 40 Kuiper Belt objects. Even though we only flew super close to one Arrokoth, we've studied a lot of them that went by in the distance and learn things that you cannot learn from Earth or Earth orbit because we're much closer and we see them from different angles. In addition, we've looked back in the distance at Uranus and Neptune and see them from their night sides, which no other spacecraft can do.

And learned things about their atmospheres and energy balance. We've also looked at the entire universe, literally mapped the sky for the cosmic optical and ultraviolet backgrounds and learned made the most sensitive measurements anyone has ever made or can make because we're so far out, all the dust of the inner solar system is nowhere near, and we have much clearer review of these things, astrophysically. And on top of all that, what you were just talking about is our ability to take this much more modern instrumentation and some new types of instruments for studying the outer heliosphere.

And just as Voyager did a generation ago with 1970s gear on board, follow that whole transition from the sun's environment through what's called the termination shock, and then the passage into the interstellar medium through the heliopause, but do it with this much more modern gear with instrumentation that can really follow up on a lot of the mysteries that Voyager data exposed. So it's very exciting and on top of it, we're the only spacecraft out there, as you say, and there's nothing else in the Kuiper Belt or the outer heliosphere. And moreover, there's nothing else planned to come this way.

So I'm sure there will be missions in the distant future, but they're not even on the drawing board, much less in flight. We're kind of it for more Kuiper Belt exploration and outer heliosphere exploration for decades.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Which is why I'm so hoping that this mission gets what it needs to continue on. What do you think the public and policymakers should know about this mission or why should they care so deeply about making sure that New Horizons keeps going?

Alan Stern:

Well, I guess there are a lot of reasons, and I am just going to focus on a couple. One of the things that this kind of exploration does is that it inspires the younger generation to go into hard things, technical fields. It's amazing when you talk to people in the tech industry, and I mean by that, computers, internet, AI, even biomedical, energy, any of that. And you ask them, what got you interested in science and education? It's amazing how poll after poll have shown a lot of kids get hooked through space exploration.

And then they're so interested in science and tech that they may end up electrical engineers working on advanced efficient energy systems, or they may end up in the medical field or in agriculture, but they often report by, and might start ... I was just so interested in the planets and the universe and astronomy. So that's very important that unlike just pure math, for example, or chemistry or physics, children tend to get turned on to STEM careers, through things like New Horizons and particularly really visible missions like New Horizons, that make an impression on kids.

A second thing is this is great soft power projection for the United States. Kids in every country know names like New Horizons or Hubble. They know about these missions, they read about them in their textbooks in any given language. And it's such a great image for the United States as a pioneer and as a country and society that's interested in groundbreaking new knowledge and doing really hard things that are above and beyond almost the imagination of people in a lot of countries. But we're known for doing that and doing it over and over and very, very well.

And so, I think those things, and frankly there's a competition now with another belief system in China. They're having a really spectacular growth rate in both their human and robotic space exploration and NASA is ahead of them, but it will only stay ahead of them if we keep doing all these amazing things.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's true. And these types of images, I mean, I know I wouldn't be where I am today without missions like New Horizons. For me it was things like Voyager and all the initial missions to Mars. But for this next generation, it really is. It's about striving beyond and seeing those things that no one has ever seen or discovered before. And if I was a kid, New Horizons would've been my mission. I mean, even now, I'm wearing a necklace with an image from New Horizons on it.

Alan Stern: Right on, as you should. But I talk to people all the time who are, for example, my children's age who were very young and impressionable and New Horizons made a big difference. And then, I go and talk to schools now of kids who 10 years ago Pluto flyby, but that was a long time ago for them. Some of them were just born or even not born when we launched in 2006 or when we got to Pluto in 2015. But they know all about it, and that's just wonderful on so many levels and it's a draw, as I say, for STEM education, for kids going and doing the hardest things, which I think are in tech and science.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, we're talking about the ways that this has changed people around the world, but you've been at the helm of this mission from the beginning. How do you think this journey has changed you?

Alan Stern:

It's humbling in many ways to know how we impacted people when we thought we were just out to do great science and to change textbooks by developing new knowledge, but how we actually emotionally connected with adults and children alike and still continue to do so. So that's changed me, and I have to say, I'm very fortunate that in my career I have now been on 30 space missions that have flown. I'm not talking about proposals that we tried, but actual space missions, 30 of them, and I've been principal investigator on either an instrument or the whole mission, now 15 time, so half of those.

But New Horizons seems to have a special connection to people, and that's more so than any other mission that I've been involved in and I've been involved in some really great ones. Finally, I just say that more than any other mission I've worked on is this overriding object lesson and what it means to be a great team. A great team of just regular, smart, dedicated humans who band together and do something that you leave behind as a legacy. Even after we all pass away, the knowledge that we developed and the firsts that we created will always be there.

And that team of people that worked so hard under so many ... I guess the word is so many difficulties as we were building it at very low cost and building it in record time because we had to get the Jupiter by a certain date to get the flyby to Pluto lined up. All those people ... I remember, if you don't mind one story.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Absolutely.

Alan Stern:

Right before we got to Pluto, we had been hibernating the spacecraft over and over every year, most of the time, all the way across the solar system because it saves money, when you don't have to run your mission control, and it also, saves wear and tear on all the electronics on the spacecraft that are off, when we hibernate and when we were waking up from the very last hibernation at the beginning of 2015, just six months before the flyby, our mission operations manager, Alice Bowman, came to me and said, "There are a lot of people on my team, Alan, who don't want this flyby to happen."

I said, "Alice, what are you talking about? That's all we've worked on since 2001." She said, "Because it's been a beacon in our future, and all of a sudden it's about to be in our past." And a lot of them, they don't know what they're going to do with themselves when it's not in their future, this beacon, and it really set me back thinking about that, and I realized some of that was in my own head and heart, but I hadn't quite crystallized on it. As it turns out, everybody did just fine and Pluto performed so well that everybody was so excited.

But it really shows you when you're a team and you're working against the odds, how emotionally invested people can get in the exploration and even the machine itself.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's a testament to the fact that these missions mean so much to people that they can act as this beacon for the future. And that's why it's so important that we keep working toward these goals, even if it seems absolutely wacky to most people to try to send something all the way out to Pluto, that's an aspiration that you can hold onto for decades, and I'm hoping that we can create so many more of these opportunities in the future. Just imagine what we're going to be looking forward to in 100 years.

Alan Stern: No doubt. I hope those in the medical field make it possible for all of us to see how the story turns out 100 years from now. It's going to be spectacular.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thank you so much for joining us to mark this beautiful occasion. I know I'm going to be reflecting on these images and maybe see if I can make a Pluto cake or something, but I hope you have a wonderful time at the conference with everyone and a good emotional moment, really filling the impact that you all made on everyone around the world, because you should be so proud.

Alan Stern: Thank you. I'll relay that to the team when we have our get together Monday night and thank you Planetary Society, and thank you Sarah for Planetary Radio being interested in New Horizons, what we're doing now and what we've been able to accomplish as a team.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks so much, Alan.

Alan Stern: Take care.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

New Horizons didn't just give us stunning images. It delivered a treasure trove of data that scientists are still working through a decade later. One of those scientists is Dr. Adeene Denton, a NASA postdoctoral program fellow at the Southwest Research Institute. You may remember her because Adeene has joined us on Planetary Radio two times in the past year, wants to talk about the origins of Pluto's iconic heart shaped feature, Sputnik Planitia. But then again, to talk about her fascinating research on the formation of Charon, Pluto's largest Moon.

Her work combines geologic analysis with impact modeling to reveal how these icy worlds have evolved over time. Basically, she likes to simulate these worlds and blow them up and see what happens. Adeene is fresh back from the progress and understanding the Pluto system 10 years after Flyby Conference, at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. Hey, Adeene, welcome back.

Adeene Denton: Hi. It's always good to be back.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I tell you last week, I was doing a live stream, celebrating the 10-year anniversary of this flyby of Pluto, and the amount of things that I've learned from you in the past few conversations we've had were just really instrumental in that conversation. So I wanted to thank you first off for helping educate me on what's happening currently in Pluto Science.

Adeene Denton: Well, it's an honor that you feel that way, and it's always really exciting to share with people, the incredible things that we've been able to learn since New Horizons did its flyby 10 years ago.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I know you probably bumped into Alan Stern at this conference. He mentioned to me he was going to be going there and he was looking forward to maybe seeing you. Did that actually happen?

Adeene Denton:

Yes. We crossed paths several times though. Alan is a very, very busy man, so we waved high. We said, great talk, great talk, and we had to keep it moving because there's a lot of science being done at this conference and a lot of people to talk to. He probably mentioned this, but it really is incredible to be able to pull together almost 100 people to get together for a week just to talk about Pluto and the Pluto system specifically. That's not something that ever really gets to happen.

And it's a testament to what New Horizons has done that's so many people have been able to do work on Pluto and advanced science so much that we now know enough about Pluto to talk about it for a full five days.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, that's a lot of science going on, and I'm sure we can't run through all of it, but I wasn't there. What were the most exciting things that you got to be there to witness?

Adeene Denton:

So many wonderful things happened last week. We got a preview of the upcoming soon to be released Pluto geologic map that was approved by the USGS and is going through pre-printing. So now everybody will soon be able to have their own Pluto geologic map and the people that do geologic mapping, I've always found so fascinating, even though I don't do that kind of work because it really is kind of at the absolute frontier of knowledge, right? When you are the one to look at a planetary surface and say, "This is a crater, this is its name."

This is the boundary of this mountain chain. Someone is drawing those lines on a map, and they're the first ones to ever actually map Pluto in that kind of detail, and I've always found that work absolutely fascinating. And then there's of course been some really incredible telescopic observations, including work done by the new JWST mission that has been able to look at the Pluto system and Pluto's moons in more detail, as well as conduct observations on other Kuiper Belt objects, which means we now have more information to compare Pluto to other large Kuiper Belt objects out there, which is I think really exciting.

Because as we move forward, and we're not necessarily going to get back to the Kuiper Belt anytime soon, leveraging what we learned from New Horizons with ongoing missions like JWST, means that we can really learn a lot more, not just about Pluto, but about other really, really cool objects that are also three billion miles away. There's still much more to learn about Pluto, especially because the surface that we saw following the flyby is incredibly geologically complex, which means that it's probably still active right now.

The surface of Pluto has probably changed in ways that we can't really imagine since we saw it 10 years ago. Those glaciers that we saw carving through the mountains made of water, ice are moving. And that means that if we ever do return to Pluto, the surface could look completely different, but until then, we can use telescopic observations from the earth and from space like with JWST to kind of check back in on the system.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are there any other cool results that you saw while you were there?

Adeene Denton:

Yeah, I think some of the really interesting work that I saw was some ongoing discussions talking about the potential for Cryovolcanism on Pluto and how potential Tectonism may have been involved because there's been suggestions, since the New Horizons flyby, about Cryovolcanism on Pluto because there are these putative cryovolcanic features. And when I say putative cryovolcanic features, what I mean is they saw a couple of mountains that have depressions in their centers similar to a volcanic caldera.

And it's kind of hard to make that happen without volcanism, which is why everybody suggests, "Hey, maybe it was cryovolcanism, that would be super cool." But the ongoing problem has always been how do you make cryovolcanism actually work? Because in regular volcanism, what happens is you melt rock. And when rock becomes liquid rock, also known as magma, it's less dense than the surrounding rock, so it wants to go up, so it's buoyant, which means eventually, most of the time it can erupt.

That's not true if you melt ice. When you melt ice, you get liquid ice, which is also known as water. And water as many of us know, is more dense than ice. It doesn't want to go up. So the question has always been okay, if what we're seeing on Pluto is a cryovolcano, that's super cool, but what happened at Pluto to make the water want to go up? And the answer for that is usually you need to exert some kind of pressure. So the ice shell needs to be putting pressure on the water such that it's basically forced out.

So some of the research that we saw at the Pluto conference was looking at what kinds of tectonism may be involved in the ice shell that could then produce cryovolcanism. And Cryovolcanism is such a great topic because everybody ... Everybody gets so frustrated thinking about how it clearly happens. There's clearly evidence for it several places in the solar system, but we really don't understand how it works.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I know we can't go through an entire week of science, but were there any fun events there? Did you guys have any parties?

Adeene Denton:

Well, I think planetary scientists love a good party to celebrate missions and the work that goes into them. So we did have a party ... Well, party is a strong word because there wasn't any cake, and I was really sad about that. But we did have a party of sorts where a bunch of members of the management team behind New Horizons did a sort of panel discussion talking about with slideshows, with slides that had pictures of the development and the struggle to get the mission funded and then up and running and then actually running the mission.

So it was really, really neat to see people talking about the prolonged history of New Horizons because the history of people wanting to go to Pluto dates back to the Voyager era. So it was kind of a celebration of all of the multi-generational work that goes into sending a mission to the outer solar system, because the people that started advocating for a dedicated Pluto mission in the late 80s, early 90s, or in their late stages of their career, but the people that are now at the forefront of doing Pluto Science and utilizing New Horizons data are at the start of their career.

So it's a celebration, not just of Pluto and everything we've learned and of new Horizons and everything it did, but also a celebration of the act of science itself, which is the idea that everything that you do and everything that you work on to push the boundary of science forward is possible because of the people that came behind you that did their work, knowing that we are working on problems that will never be solved within one lifetime. And to me, that was a really, really cool and really profound experience to be a part of.

One really neat thing that happened is at that celebration, I was actually able to meet the guy that discovered Charon in 1978. He was there with his wife, and I got to meet him and tell him that my work is looking at how Charon formed, and to be able to show him some of the same videos that I've showed you and your guest from the work that I published this year, and he was so excited to hear about the work that's still being done on a body that he discovered. And I think that's one of the cool things about doing science in the Pluto system is that Pluto itself, our understanding of Pluto is so new.

That the guy that discovered its largest moon is still alive. To be able to come to these events and be amazed and thrilled by the work that people are doing today.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, I get emotional just hearing that. That is such a profound experience to be able to share that with that person. My gosh, from me to you and everybody that's either worked on this mission or has worked on the data from this mission, thanks for doing so much to help reveal this world that I think holds such a special place in people's heart. Pluto is so special to so many of us, and I am so glad you're here to share this with us.

Adeene Denton: My pleasure.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, before I let you go, what's next in the adventures of Adeene Denton and learning more about this system?

Adeene Denton:

Well, I don't currently have funding to do more Pluto research at this time. I'm currently looking at some of the mid-sized moons of Saturn to try to better understand how icy bodies like Pluto become geologically active or not, because we still don't understand why Pluto being three billion miles away and not even around a giant planet is still so geologically active. There's more questions when we get to some of the other icy worlds in the solar system because you have Enceladus, which is the satellite of Saturn that is incredibly geologically active, has the geysers coming out of its south pole.

But the moons to either side of it aren't nearly as geologically active, and we don't fully understand why that is. So in trying to understand the history of those bodies, I'm hoping that we can try to build a much more broad understanding of what dictates geologic activity and habitability on icy satellites across the solar system. So I'm really excited about that work and what that means in practice is I'll be blowing up those moons as well, because all of them have really, really big impact craters.

So I'll be hitting each of these moons in turn and seeing what happens, and then be able to compare that to their existing geology and also to Pluto to try to understand things a little bit better.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Seriously, just so much fun. Just blow up worlds in the solar system, see what happens, and learn the science. I love your job.

Adeene Denton: I love it too.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, seriously, good luck on your adventures, and when you learn more about those moons, let us know.

Adeene Denton: Can do.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Bye Adeene. As we celebrate everything New Horizons has accomplished, it's important to remember that missions like this and the entire future of space science in the United States are under threat. NASA's science program is facing a proposed 47% cut in 2026. If enacted, this would force the early termination of dozens of missions, including New Horizons, halting scientific progress across the agency, and causing the United States to cede its leadership in space exploration and discovery.

At The Planetary Society, we're working every day to protect NASA's science programs and to stand up for the scientists, engineers, and missions that make exploration possible, and we have huge news. The advocacy of all of the space fans around the world is working here with a major update from Capitol Hill is our director of government relations, Jack Kiraly. Hey, Jack.

Jack Kiraly: Hey, Sarah. How are you doing?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, it's been a while since we got a space policy update on the show. There's been so much going on, and I'm glad that we can take the time in a show celebrating the New Horizons mission to talk about this, because New Horizons is one of those missions that's being deeply impacted by space politics right now.

Jack Kiraly: Yeah, and New Horizons has had a long history in space advocacy and space policy. Yeah, this is just ... That next hurdle right now is this current year, fiscal year 2026 appropriations process and setting that budget for NASA, which includes operations for our friends, Alan and company over at New Horizons.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What's been going down in Congress with this?

Jack Kiraly:

Yeah, so we've had an incredibly busy and productive few weeks here in DC. I know those words don't tend to go together, but when it relates to our Save NASA Science campaign, we've had some major developments that have really moved the ball forward. Just as a little reminder, so President's budget request this thing that's proposing 47% cut to NASA science, an overall 24% cut to NASA gets released in the early part of the year. Every year this happens, gets released, goes to congress. Congress says, thank you very much.

They put it in the circular file and start their own process, and the House and the Senate go to their subcommittees and they work out a deal on the funding for NASA as well as all the other agencies. And it filters up through the Congress and ultimately becomes law. We're in that sort of middle part of the process, where the appropriations subcommittees, which appropriations is what we call the appropriating the establishment of funds for specific activities within the government.

The appropriations committees have met, it's the end of July. We now have two bills, one in the House and one in the Senate. Both of them keep the NASA top line budget flat.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man.

Jack Kiraly:

You know what that means? That means no cuts, no top line level cut for NASA. Congress has in this moment, July, 2025, has taken the input from the administration in their budget request and have said, "No thank you." They have outright rejected in a bipartisan manner, at least over on the Senate side, outright rejected the President's budget request. And even on the House side, there are issues relating to Department of Justice and Department of Commerce right now, that have polarized some of the committee work.

But NASA has been a uniting factor, we've seen in opening statements from Republicans and Democrats. Both sides of the hill, how important NASA is and that the Congressional intent ... That's the key word, congressional intent of both the House and the Senate, is to keep NASA whole. This is a huge moment for the campaign. If you've written a letter, if you've visited your member's office. If you've written an op-ed, if you've called your representatives in Congress, like I know tens of thousands of people have over these past five months.

This monumental decision by both chambers of Congress to reject the cuts and keep NASA whole, this is for you. This advocacy that you've been doing has worked. Now the details, right? House still it includes a small cut, the rebalancing of funding within the agency. They do have about a billion dollar cut to science. But even just from some of these initial conversations, it seems like keeping that NASA top line budget flat is the key point. They bump up to get to that overall top line, keeping that flat for NASA, the human space flight program gets a bit of a bump up.

We talked about this capital B budget, the reconciliation HR one, has all these different names that passed earlier this year, has supplemental funding for human space flight that can totally offset this bump that the house has included and make science whole. And that's from having these conversations on the hill. So even though the house has advanced a bill that some of the finer details aren't exactly what we'd like, there is still an effort happening in the House of Representatives to rebalance their budget and make sure that NASA science is whole.

So all of this has led up to this moment. And I'll say this, in a normal year, this would be a crescendo moment and it's still very important. But the problem is we're not in a normal year, right? It's still very important. We have now gotten flat funding into both the House and Senate bill prioritizing key projects and program areas within both bills that we support, and that is laying the foundation for whatever budget Congress ultimately passes.

But what we're hearing is that even though congressional intent has been made clear, the Office of Management and Budget, that group of unelected bureaucrats over at the White House, whose ultimate goal as an organization in the federal government is to execute, so it's the executive branch, to execute the laws passed by Congress. That's currently in question. As we've heard from OMB director Russ Vought, they're questioning that Article I section IX, Authority of Congress to appropriate funds. Congress takes that very seriously, that their role is to set the budget and the policy of the United States, and it's the job of the executive to execute.

But we're at a now, where we have, I'll say a rogue OMB director who isn't even totally aligned with the president on his goal for a strong space program as President Trump has been in the past and in public statements has been that OMB director Vought is trying to usurp some of that congressional authority. This is not something that normally happens. And so we have to do a lot more fighting because we have this OMB director who is making plans to terminate missions early, has cut funding for scientific research opportunities in the science mission directorate at NASA by 82%.

Has led the more than decimation, almost a double decimation of the NASA workforce as of public reporting, we know about 2,600 people have taken some of these deferred resignation programs, these early leave programs, a lot of them in senior leadership at the agency, people with a lot of expertise and know-how on executing successful space missions.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh man, that's devastating.

Jack Kiraly:

All that's still happening, right? And Congress is making it clear like they're putting their foot down and saying, "Hey, remember we write the laws in this country. We appropriate the taxpayers funds. We are the ones responsible for doing those activities," and they're making their case and making it known that they support. In the case of NASA. Very strongly support keeping NASA whole. Now we're entering this phase where Congress is going to need to start pushing back more significantly to some of these cuts that are being made.

And so that's why I am having a great day, great week, I think this week, better week than I've had at any point in the last five months, but it is not causing me to relax. This is a moment that I'm channeling these good feelings about where we are into this next phase of advocacy.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It makes me feel very hopeful and very grateful that so many people have been doing so much advocacy for NASA science. I mean, that is absolutely monumental and I feel like we all deserve to take a moment to really be joyous that this is the result that Congress is actually listening, but it also makes me feel even more invigorated to feel like this is the time to double down. We need to be louder than ever because you're right, this really isn't a normal year. And so we're going to have to push harder than ever to make sure that we can actually get this funding.

Jack Kiraly: These things are moving the needle. So take solace in the fact that what you've been doing to the tens of thousands of people who have been doing something these past few months, that it is working, but it's not time to hang up our hat and go home. This is time to double down.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This is the good news that I needed.

Jack Kiraly:

Really, this has been such an amazing effort by our team from leadership on down to get to this point and for every person that wrote a letter for every show that you've hosted and conversation that you've had to every visit that we've had on the hill, all of it has made such a tremendous difference. And I hear that constantly from members of Congress and their staff who contact me. We've gotten to the point where people are reaching out to me. I'm not just the one bug in them, but people are reaching out to me and saying, what your organization, planetary Society.

And it's supporters and members have been doing, has really shaken things up in a good way. We're not giving up. This is a point where we should celebrate and we should take to heart that what we've been doing has worked and redouble those efforts and get ready for what is going to be the next five months or six months of groundwork, making sure that we get this budget passed, making sure the executive branch knows congressional intent is clear, making sure that the budget is executed appropriately, that we keep these missions flying. We keep doing this science, we keep advancing humanity into the cosmos.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, let's get out there. Let's save NASA science, and thank you so much, Jack, for being here. I needed some good news.

Jack Kiraly: Thank you, Sarah, and yeah, happy to deliver it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As Jack said, we're making major progress, but if we're going to save NASA science from this massive cut, we need to continue advocating now more than ever. The Planetary Society is lighting the beacons. NASA science calls for your aid. To join our fight, go to planetary.org/savenasascience. Now it's time for what's up with our chief scientist, Dr. Bruce Betts. Hey Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hello, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was cool to finally get to talk to Alan Stern after watching this mission for so many years and seeing so many talks with him online and knowing the long history of The Planetary Society working with this mission, it was awesome to just actually get to talk to the guy.

Bruce Betts: It's an amazing mission and congratulations again to all the team, including Alan that made this happen over, all the many, many years and through the cancellations and through the planets and through the hibernation and through space.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I did a live stream with someone on Twitch recently, and because of that, we were going to be talking about this Pluto anniversary. And I learned a whole lot more about the history of just the slog to try to get out to Pluto. I did not know, and maybe I should have known this, but I did not know that they had to not go out to Pluto with the Voyager mission in order to divert to Titan. What an interesting history there. That is a long time, it took us to make that mission possible.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I mean, Voyager was even more complicated. They were also choosing between Titan and having a second spacecraft. It could have gone to Uranus or Neptune. So anyway, it happened and it was amazing, and I'm sure you've discussed that and the many surprises we saw,

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But we didn't get a chance to go too deeply into Arrokoth, that second object that it went by in our main interview. So I wanted to ask you what made that little Kuiper Belt object such a big deal for us to understand how planets form?

Bruce Betts: Arrokoth was exciting in principle because it represented a size and location of object that we hadn't seen in the tens of kilometers diameter range, and then way out there in Kuiper Belt land. And then, when we actually saw it and it looked like a snowman, that's just exciting in and of itself. Then the fact that it was a contact binary and it was telling us something about how things come together in the solar system and just yet another weird different body. I mean, it may not be weird. There may be lots of them out there, but it's first time we saw this icy contact binary, much less way the heck out there, the most distant object we've ever visited.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It looks kind of like ET to me. I don't know if that's just me.

Bruce Betts: I think it's just you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It maybe, if you rotate it just a little bit, there's those little dimples in there that look kind of like a face. But I mean, the fact that it's a contact binary at all, and we've been seeing a lot more of these kinds of objects as we've been exploring asteroids and the moonlets and stuff like that. That is really interesting and I guess it shouldn't be surprising because things out there aren't really going through high speed collisions that often, I guess. But even that's interesting for planetary formation

Bruce Betts: It is. Well, I mean they're going through high speed collisions that stick and really high speed collisions that break things apart, and then sometimes apparently gently coming together and forming these contact binaries both in asteroid land and in icy object land based on Arrokoth.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Cool name too. Love that. What do we got for our random space fact?

Bruce Betts: Well, we'll go to a random space man. We're going back to Pluto. We're going back to Charon. So the surface area of Pluto makes it ... If you translate to what it would be on Earth, is a little bigger than Russia, Service area of Charon is somewhat bigger than India and smaller than Australia.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's actually a great way to visualize that. I had already had the one for Pluto in my brain.

Bruce Betts: Right.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, that's a really great comparison. It really does show the size scale comparison there in a way that it's easier to understand.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Qualitatively overstate the obvious. Pluto is bigger, but Charon is significantly smaller, but not that much. It's still a big country on earth. The population is low, but the service area is pretty big. All right, everybody go out there and look up the night sky and think about ... I'm just stuck on marshmallow filling these days, but think of a marshmallow filling inside a planet. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week to learn all about Sleeping in Space. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio t-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary radio.

You can also send us your space thoughts, questions and poetry at our email [email protected], or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our dedicated members all around the world who once upon a time, saved new Horizons. You can join us as we work together with all of our people around the world to fight for space science and exploration, at planetary.org/join.

Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Casey Dreier is the host of our monthly space policy edition, and Mat Kaplan hosts our monthly book club edition. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. I am your Planetary radio host and producer Sarah Al-Ahmed, and until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth