Planetary Radio • Dec 10, 2025

Inside the 2025 Mars Society Convention

On This Episode

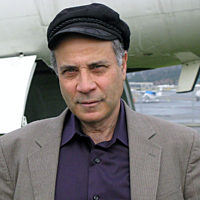

Robert Zubrin

Author and Founder for The Mars Society

Humphrey Price

Chief Engineer for NASA's Mars Exploration Program

Steven Benner

Distinguished Fellow for The Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Also in this episode:

- James L. Burk, Executive Director, The Mars Society

- Dex Hunter-Torricke, Former communications leader for SpaceX and Meta

- Tiffany Vora, Vice President for Innovation Partnerships, Explore Mars

- Erika DeBenedictis, Founder and Biotechnologist, Pioneer Labs

- Melodie Yashar, Architect and CEO of Aenara

- Sasha, 13-year-old presenter and Convention attendee from Vancouver, BC

The 2025 International Mars Society Convention convened at the University of Southern California this October for three days of passionate discussion about humanity’s future on the red planet. Speakers explored science, policy, technology, AI, synthetic biology, and the long-term path toward becoming a multi-planet species.

In this episode, Mat Kaplan, senior communications adviser at The Planetary Society, shares his conversations with speakers and guests at the Convention. We hear from Robert Zubrin, founder of The Mars Society, who delivered a fiery call to protect NASA’s science programs in the face of unprecedented budget cuts. Humphrey “Hoppy” Price, Chief Engineer for NASA’s Robotic Mars Exploration Program at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, updates us on the future of Mars Sample Return and new mission architectures. Keynote speaker Dex Hunter-Torricke, a longtime communications leader for SpaceX, Meta, and other major tech organizations, reflects on AI’s promise and peril, and why Mars remains a beacon of hope for humanity’s future.

Biologist and technologist Tiffany Vora, vice president for innovation partnerships at Explore Mars, and Erika DeBenedictis, biologist and founder of Pioneer Labs, reveal breakthroughs in synthetic biology and engineered microbes that could help future Martians survive. Steve Benner, chemist and founder of the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution (FfAME), revisits the Viking lander experiments and makes a provocative case that we may have found Martian life nearly 50 years ago.

Architect Melodie Yashar, CEO of AENARA and a pioneer in 3D-printed habitat research, shares progress in additive construction on Earth and Mars. James Burk, executive director of The Mars Society, discusses advocacy, analog research stations, and the organization’s expanding international footprint.

Finally, we meet Sasha, a 13-year-old presenter whose enthusiasm offers a bright glimpse of the next generation of explorers.

We wrap up the show with What’s Up with Bruce Betts, chief scientist at The Planetary Society, with a discussion of perchlorates in the Martian soil.

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Mat Kaplan brings us inside the 2025 Mars Society conference this week on Planetary Radio.

I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. This week, we're headed to the University of Southern California, where the Mars Society's 2025 conference gathered scientists, engineers, advocates, and simply the Mars curious. Our own Mat Kaplan, senior communications advisor at The Planetary Society, was there, collecting conversations with some of the most passionate voices in the Mars community. You'll hear from Mars Society founder, Robert Zubrin, who opened the conference with an urgent call to protect NASA's science programs. Then, Humphrey Price, chief engineer for NASA's robotic Mars Exploration Program at JPL. He shares the latest on Mars Sample Return and the challenges facing the Mars Ascent Vehicle. You'll also hear from Dex Hunter-Torricke, former SpaceX and Meta communications leader, on AI, humanity, and our potential multi-planet future.

We'll also hear some groundbreaking biological research with Tiffany Vora, vice president for Innovation Partnerships at Explore Mars. And Erika DeBenedictis, founder of Pioneer Labs, who's bioengineering hearty microbes that might one day help us survive on the Red Planet. Steve Benner, chemist and founder of the Foundation of Applied Molecular Evolution, revisits the Viking lander experiments and makes a provocative case that we may have found Martian life nearly 50 years ago. Then, architect Melodie Yashar, who's the CEO of Inara and a pioneer in 3D-printed habitat research, shares progress in additive construction on Earth and Mars. We'll also hear from James Burk, executive director of the Mars Society, and close with an inspiring conversation with Sasha, a 13-year-old presenter who's already spent three years sharing his passion for space exploration. And of course, we'll wrap up with Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, for What's Up, as we have a discussion about perchlorates in the Martian soil and why we need to solve that problem before we can send humans there for permanent settlement.

If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

Mat Kaplan was the host and producer of Planetary Radio for 20 years, and he continues to serve The Planetary Society as our senior communications advisor. But it was another society that brought him to the University of Southern California campus in Los Angeles back in October. The Mars Society is the world's largest organization dedicated specifically to the human exploration and settlement of the planet Mars. USC hosted the 2025 Mars Society conference, an annual gathering of would-be Martians and other space nerds. Here's Mat's report.

Mat Kaplan: We begin our coverage of the Mars Society conference with the person who founded the organization back in 1998. Dr. Robert Zubrin electrified the space-exploration world in 1990 with his Mars Direct blueprint. He was already frustrated by the on-again, off-again plans to get humans to the Red Planet. So he developed an architecture that could get us there quickly at relatively low cost and with mostly existing technology. That was 35 years ago. Zubrin has no less passion for Mars today and has written several books on the topic. I talked to him about his latest, The New World on Mars, when we made it our May 2024 selection for The Planetary Society Book Club. So it was no surprise that he helped kick off this year's conference with another impassioned plea. The difference this time is that it was a plea for all of science.

Robert Zubrin:

This is a moment of crisis and opportunity, although I have to say that the crisis part is looming a lot bigger right now. It's a good-news-bad-news situation. The bad news is that the NASA space science program is under severe attack, severe. This is not a small attack. The NASA budget is being cut by about 6 billion overall, and 4 billion of that is going to the quarter of NASA that is the space science program. This is the part of NASA that does the Mars rovers and orbiters and the probes to Jupiter and the New Horizons to Pluto and Hubble and Webb and the other space telescopes and all the Earth observation satellites as well. It is the part of NASA that, since Apollo, has been responsible for at least 90% of all NASA's real accomplishments. It is the purpose-driven part of NASA. So, they're cutting 6 billion from NASA, and 4 billion of that is being directed at the best part of NASA, the very best, the part that makes it worthwhile.

They're talking a big game. "Oh, we're going to the moon. Then we're going to go to Mars. So don't worry about this." The highest ideal of contemporary Western civilization is freedom. And science is the child of freedom. Free inquiry is what produces science. The fruits of science is technology, and anybody can use that. But science itself comes from freedom. Now, admittedly, space science is not all science, but it is the greatest symbol of science in our age. It is the banner of science. It is for the scientific worldview what Gothic cathedrals were to the religious worldview of the Middle Ages. Those were represented concrete symbols of the value that those societies put on their highest ideals.

Well, the NASA space science program has astounded the world with the things that it does. It is the Hubble and the images from Hubble and now from Webb taken of the outer planets and so forth by these various probes. And yes, from the surface of Mars. These are the Gothic cathedrals of our time. This is the banner of the scientific worldview. This is our flag. And they're burning our flag. That's what they're doing. They're burning our flag when they destroy this program. And it cannot be tolerated.

So, to save not just the humans-to-Mars program, but to reaffirm the highest ideals and the most productive ideals of our society, we need to repel this attack. And that is why the Mars Society is going to mobilize to contact Congress, to mobilize chapters in every district, to go to speak to anybody in Congress or the Senate or who can reach them and say, "This must not happen. We can't let them burn our flag, and we're not going to let them burn our flag." Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Old friend Humphrey Price drove over from the Jet Propulsion Lab, where he serves as chief engineer for NASA's robotic Mars Exploration Program. Hoppy, as he is far better known, gave us a brief review of the somewhat precarious status of the effort. That's the Mars Ascent vehicle, the small rocket that may someday get precious samples of the planet up to orbit for their trip to laboratories on Earth.

Humphrey Price:

Mars Sample Return's been a topic of discussion. We continue to collect the scientifically valuable core samples for potential return to Earth. And the Cheyava Falls sample is particularly interesting. It may have compelling evidence of ancient microbial life on Mars. So, addressing the cost of Mars Sample Return, we have been looking at ways to implement a cheaper mission. The key is the MAV. The MAV is very heavy. That drives the mass of the whole system and, therefore, the cost of the whole system. So, we are developing a new MAV design concept that's smaller, and we're looking at a way to deliver a smaller lander using a proven sky crane approach, where we can just drop it down on the surface like we did Curiosity and Perseverance. And so, that would also be a cost savings because now we're just rebuilding the system that we already have.

And of course, industry is looking at alternatives for a large lander to bring a MAV to Mars and be able to bring the samples back. And so, NASA still has not made a decision on Mars Sample Return. The funding for that is still in question. But we still do have people working Mars Sample Return at JPL and at other NASA centers. And ESA continues to develop the Earth Return Orbiter to bring the samples from Mars orbit back to Earth. They're fully funded, and they do plan on building that orbiter and launching it. And I need to make sure I make it clear that this is a concept. Mars Sample Return is not a program that's been given the go-ahead. And so, I'm giving this information just to let you know where we stand right now.

Mars Exploration Program has released a future plan that incorporates inputs from across the planetary science community, and we do have a big science community, international one. So, looking forward, we plan to implement a sustainable portfolio of missions that can address our critical and aging infrastructure. The Odyssey and MRO are getting kind of old, and we could lose our high-resolution imaging capabilities. So we'd like to have a replacement for that, and also to replace our relay orbiters and many other capabilities that we have for science instruments.

So, looking at future Mars opportunities, what we want to do in our future plan is to establish a regular cadence of science-driven missions. And that runs the gambit from low-cost missions, which is what Robert was talking about, doing a lot of low-cost missions. And we are looking at options for that. Medium-class missions and also missions of opportunity that might be competed payloads or ride-shares with other missions that are going to Mars, maybe even commercial missions. And some of those could even be possibly flagship-type missions. So, the low-cost missions are in the 100 to $300 million range. Medium-class missions would be a little bit more. And then there's the missions of opportunity. So you can read more about those in the future plan.

So, some of the things we'd like to do are monitoring and predicting Mars weather. We know that there is methane that seeps out under the surface of Mars. The Curiosity Rover has a methane detector, and we occasionally see methane. It tends to be seasonal in Gale Crater. And so it's possible that the methane could be from subsurface microbes generating methane, or it could be for some kind of subsurface geothermal activity. And so, we'd like to learn more about that. We'd like to be able to determine the location and nature of those methane seeps.

We want to do ice mapping from orbit. There's been an international study for the International Mars Ice Mapping Mission. And right now, that's not been approved, but still being studied. A lot of work has gone into that to try to characterize where the ice is on Mars.

And then, in the decadal survey from the National Academy of Sciences, they make their decadal recommendations. And one of the higher-priority missions is the Mars Life Explorer, MLE. We also call that the search-for-life experiment. And so that would be to go to a region like Arcadia that we know has subsurface ice, not very deep layer of topsoil on top, maybe a meter or less of topsoil in some locations. So we'd like to drill down into the ice and actually have a life-detection experiment, as Robert was pulling for, to see if there might be a microbial life that exists in the ice at a depth where they would be shielded from the galactic cosmic radiation that we see on the surface of Mars.

We put a lot of effort, MLE experiment that was in the decadal survey, to show that we could have a sterilized system that can drill into the ice and be able to take measurements with systems that are all sterilized so that we can be assured that we're not injecting any Earth microbes into that. And I think a good test case is actually the sample tubes that we have on the Perseverance Rover. So, we had a requirement on Perseverance that the sample caching area and the tubes had to have less than one microbe on them. And so we went through this tremendous verification program. And I think we demonstrated that the system we have on Mars right now with Perseverance, the areas that are contacting our samples don't have any microbes on them. So that way, when we bring back the samples, if we see something, we can hopefully be assured that it's not an Earth microorganism because we didn't send any there.

But just to be sure, we also take swab samples of everything in the clean rooms, and we do a genotyping of them, and we have them all in a database. So if we see something coming back from Mars, we would definitely check with our genomic inventory database to make sure it wasn't one of the critters in our clean room. And we do have all kinds of critters in the clean room that have evolved to survive only in clean rooms. Life is tenacious. But anyway, we have pretty good confidence that we'll be able to meet the planetary protection requirements in a search-for-life experiment.

There are a number of companies that have expressed interest in providing commercial service carriers for delivering multiple spacecraft to Mars in different ranges of sizes. And that could include flyby missions, orbital missions, and/or lander missions. NASA did fund studies last year for a number of commercial concepts. So, Firefly has a concept for a commercial Mars mission. So does Impulse Space, Lockheed Martin, Astrobotic. Blue Origin has their Blue Ring system, which can be adapted to send multiple payloads to Mars. And then ULA has a concept using their upper stage with a sunshade. That's actually a LOX/hydrogen system to carry a number of payloads to Mars.

Mat Kaplan:

Hoppy Price of JPL. There was a keynote speaker at the conference whom I'd never heard of. Dex Hunter-Torricke didn't confine his remarks to Mars, but it's safe to say that he made a big impression on attendees with his polished and zealous talk. It was about both the enormous promise and disturbing threat of artificial intelligence and the future of humanity here on Earth and across the solar system. Dex spoke with the authority he gained in 15 years of work for the likes of Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg. I caught him shortly after his talk.

So, Dex, I almost regret that I have to, in this conversation, stick to the Red Planet, because your talk encompassed the cosmos, at least the human cosmos, in a sense. I can tell you that that was among the most exciting, inspiring, and disturbing presentations I've ever heard, and I include every TED Talk I've ever heard. Please take that as a compliment.

Dex Hunter-Torricke: Brilliant. Well, look, the future is extraordinarily exciting and inspiring and also deeply disturbing. There are things happening in the world today which are extraordinarily disruptive for societies. And I mean that in the true sense of disruption, something that is very unsettling and is profoundly challenging for people. And there are also, at the same time, things that are deeply hopeful and wonderful and might lead us to a vastly better world. And the challenge for so many leaders and institutions today is they only have the capacity to spot one thing at a time. They can only pay attention to one set of trends. It is the year 2025. We live in a time of extraordinary complexity. If you want to be a relevant leader with plans that are going to work, you must be able to pay attention to more than one thing at the same time. And that's why I talked about everything I talked about today.

Mat Kaplan: You talked about worldbuilding. We're certainly talking about world changing. Where does another world, where does Mars come into this?

Dex Hunter-Torricke:

Why did I get into working for Elon at SpaceX in that earlier time when he was still a hopeful figure? Why do all of us care about Mars? I mean, I'm sure we're challenged, we're asked that all the time, usually by some smart mouth at a dinner party or at Thanksgiving. They're like, "Why don't we just focus on Earth's problems?"

And look, everything I said was clearly, I'm a person who's serious about solving our problems on Earth. That's where humanity lives. But Mars is part of our future. It is another plane of existence for us that we will reach if we play our cards right. And it represents to me a very tangible milestone for where our civilization could go that is deeply, profoundly hopeful. And it is a planet with as much land surface area as the Earth, right? It's something which will take us in all sorts of new ways to frontiers that will explore science, which will allow us to explore ourselves. But we have to get there and still be the people we want to be.

And that's why everything I talked about is, the journey to Mars and how we get there in one piece also requires us to fix Earth. It's not an either/or choice. But we need to be able to pay attention to both things if you want to build a multi-planet civilization. The first planet we live on, the one we all live on, is this one.

Mat Kaplan: What do you say as we head into this difficult time to my nine-year-old grandson?

Dex Hunter-Torricke:

I would say to your nine-year-old grandson, look, I don't know you, but I want you to have a good life. And your family and my family and a lot of other people, we are not giving up on the future, the good future for you. And we are working as hard as we can so that all of us survive in our time, so that you in your time get to thrive and build a civilization that truly thinks of the ambitious, creative, wonderful future, which might involve building other worlds, as a birthright for all people, not just something that belongs to a tiny sliver of the world's most well-off people in a few parts of the world.

And this is something which I don't know if we're going to succeed, but we're not going to give up. And what I need you to do there in your life is get ready to be part of fixing these problems and to still have creativity and joy and love of living that all kids have if they have those opportunities when they grow up and bring those into the fight, because we can't despair. If we do that, then we truly are lost.

Mat Kaplan: Hear, hear. Brilliant, Dex. Thank you so much. I cannot wait to hear about those plans, those next steps in your life.

Dex Hunter-Torricke: Brilliant. No, thank you. And thank you for everything you're doing. It's an absolutely beautiful thing to really be inspiring and standing up for the things that everything you're doing stands for. There's a good future out there, and it involves Mars, it involves science, it involves all of these conversations.

Mat Kaplan: I didn't expect so many of the really striking conference presentations would revolve around biology, including the search for life on Mars and how biotechnology may be vital to enabling us to live there. Biologist and biotechnologist Tiffany Vora is a dazzling speaker. She's also the vice president for Innovation Partnerships at Explore Mars, another of The Planetary Society's sister nonprofits.

Tiffany Vora:

So, imagine I told you about this magical manufacturing technology that is self-perpetuating and self-repairing. It's highly modular. It's flexible in terms of the input that it takes. It is programmable and reprogrammable. It's resilient and it's remarkably stable, that if you keep it cold and dry, it'll keep running and work and wait around for you for years to decades to centuries to millennia to perhaps even more than that.

Now, the good news, of course, is we already have that technology. That technology is life. And here on Earth, we've had life for the last 4 billion years, having these properties as this type of system. But so, what we decided to do a couple of years ago at Explore Mars was to spearhead a synthetic biology working group to take a deeper look at what we would actually need in order to further biotechnology and synthetic biology specifically for space, but also with a mandate for making life better on Earth at the same time.

Synthetic biology is when we bring together things like genetics, computer science, physics, a bunch of other types of scientific disciplines, in order to program or reprogram living things to either make new things or have new functions that they didn't have before, or to improve the functions that biology has already given us. So, the overall vision that I'm selling you here is a world in which biological systems, our 3D printers, our computers, our sensors, our power plants, that help us make all the food, fuel, and fiber that we need in order to live resiliently, sustainably, and to thrive and not just survive in the places where we are, right? And that's anywhere that we call home. I love this. I mean, I'm a biologist, I'm highly biased. But today is the most boring biotech and synthetic biology are ever going to be. It's only going to get better from here.

Mat Kaplan:

Dr. Tiffany Vora of Explore Mars. It was because of Tiffany that I met Erika DeBenedictis. Erika is another biologist who doesn't just dream about how we will live and thrive on the Red Planet. Her nonprofit, Pioneer Labs, is bioengineering microbes that may be capable of surviving on the terribly harsh surface of Mars. The key is what those microbes may someday do for us.

Erika, we first met at that Mars Innovation Workshop a while back that was put on by Explore Mars. Great stuff again today. You guys are doing exciting work.

Erika DeBenedictis: Yeah, it's pretty cool. We have been trying to figure out since last year, "What is in the dirt on Mars? Could you actually grow stuff in it?" And now we have examples of microbes that can grow entirely in Mars dirt plus Mars water ice, which is pretty cool.

Mat Kaplan: And you called it a regolith recipe, and you broke it down for us on a slide.

Erika DeBenedictis: Yeah. So, we did a deep dive into if you take regolith and you add water, what is soluble, because that's the part of the chemistry that matters for living things. They can't interact with rock. They can only interact with things that are floating around in water. My team mostly comes from the biology side, and yet most of the data on what is in Mars dirt is from hardcore space scientists and geologists and chemists. Figuring out what's in the dirt has been a challenge because the measurements are so rare and so valuable. And so you have to really, really understand them deeply to interpret it properly.

Mat Kaplan: So, with your best guess, best analysis, you were able to find at least a couple of bacterial species, couple of bugs that can get everything they need maybe with one exception, and that's the acetate, which has to be made for them. Do I have that right?

Erika DeBenedictis: Yeah. So, right now, we're growing microbes that source their nitrogen and their phosphorus and a lot of their sort of trace elements directly from the dirt. So Mars dirt has all of those nutrients in it. It does also have various toxins. It has salt and perchlorate, which makes it hard for things to grow in it. But on balance, you can get stuff to grow. And yeah, the exception is the carbon. So right now, we're working with organisms on purpose that you have to feed them fixed carbon. So you have to feed them something. They don't make it themselves. In the future, probably next year, we're going to start working with photosynthetic organisms where you could just bubble in carbon dioxide atmosphere and they would take that carbon directly out of the air, but we haven't started doing that yet.

Mat Kaplan: Having to make this one, I'll call it a nutrient, that the bacteria now you would need to give them is in terms of planetary protection, right? Because if that bug escapes, it's not going to make it out on Mars. Forgive me for saying so, but it sounds like the Jurassic Park stuff. So these dinosaurs are fine. They're all female, except that life, as Jeff Goldblum so wisely told us, finds a way. I trust you said you can say with certainty if these bugs were on Mars, we'd be pretty safe and we could use them to do useful things, like bioremediation, turn perchlorate into stuff that isn't nasty, right?

Erika DeBenedictis:

Yeah. As you say, never say never. Life finds a way. And that's part of what's cool about it as a technology. It's self-evolving. It'll get better with time. Now, I am not expecting photosynthesis to evolve de novo on timescales that we're worried about. I think we would notice. So that's one thing I'm not worried about, and that's why it makes it a really good planetary protection check. Because yeah, it's not going to magically become an autotroph. Quickly, at least. We would notice.

And yeah, these organisms, they have lots of use cases even when we do have to feed them, like you can remediate perchlorate in the soil, which means you could actually grow crops. You could do The Martian thing and grow your potatoes. Interestingly, The Martian was written right before we knew about perchlorate and that there's this terrible toxin that'll kill your thyroid in the dirt on Mars. And so, we now know that you have to do something to get over that before you can make potatoes. And bacteria are great at remediating perchlorate, so that's an option. Plus, an enormous number of other possible products. You can make bioplastic for building structures and greenhouses and stuff like that. And you can do it at scale because all you need to feed the microbes is raw materials you have lying around, dirt, water, and air.

Mat Kaplan: You had a slide that showed this fitting into a framework for, my goodness, terraforming of Mars, which is, I mean, really now, from what you told us, beginning to get the sort of thought and the level of examination that... Of course, it's been talked about, at least in science fiction, for decades and decades, but now people like you are actually working on this.

Erika DeBenedictis:

Yeah. I'd say in the past couple years, terraforming has gone from a fully science-fiction concept that's very cool to an actual research field that people interrogate with the same critical lens that you do the rest of science. And that transformation has happened because technology has moved on just enormously since this was proposed, just mentioned first decades ago, right? Now we have Starship. Maybe there's a few extra bits that need to work.

But, I mean, we have vastly expanded the launch capabilities of Earth. So it's now possible to think about taking mass to Mars at scale in a way that it wasn't before. We know a lot more about Mars itself and what materials are there. We know you can't just nuke the ice cap. Please don't nuke the ice cap. That won't work. But we know things that might work now. And we just have so much more information about Mars as a planet. And on top of that, we now have decades of synthetic biology that tell us the range of organisms already present on Earth that could work on Mars and how to modify them or combine their properties, which is a lot of what I work on. And so, it's suddenly, the pieces fit together in a way that's much more meaningful than they used to. And people are really starting to work on it with serious research science projects.

Mat Kaplan: These are exciting times.

Erika DeBenedictis: It is very exciting. It's really interesting for me because I both come from a space science background and a biotech background. The combination of those two disciplines. Those two disciplines have so much to learn from one another. In space science, things have to work so well, so robustly. And biotech, that's what we're bad at. We could really challenge ourselves to make microbes that are super robust and will eat low-cost feedstocks. I bang on my drum all day about this. And I think conversely, space science really needs flexible manufacturing techniques and biology... We live on this planet that makes everything for us, and we need to miniaturize those capabilities and take them with us when we go to space. And so, I'm just excited for people to talk, cross-pollinate more, have these ideas circulate.

Mat Kaplan: And judging from how in demand you've been as we tried to work our way down here to have this conversation, I'd say a lot of other folks here are also excited about that. Erika, thank you. It's great to talk with you again.

Erika DeBenedictis: Yeah, thank you so much. Nice to see you.

Mat Kaplan: Biologist and biotechnologist, Erika DeBenedictus. Time for a quick break. When we return, we'll hear about new evidence that an experiment on Mars nearly 50 years ago actually found life. This is Planetary Radio.

Bill Nye: Greetings. Bill Nye here, CEO of The Planetary Society. We are a community of people dedicated to the scientific exploration of space. We're explorers dedicated to making the future better for all humankind. Now, as the world's largest independent space organization, we are rallying public support for space exploration, making sure that there is real funding, especially for NASA science. And we've had some success during this challenging year. But along with advocacy, we have our STEP initiative and our NEO Shoemaker grants. So, please support us. We want to finish 2025 strong and keep that momentum going into 2026. So, check us out at planetary.org/planetaryfund today. Thank you.

Mat Kaplan:

Welcome back. Steve Benner delivered yet another eye-opening talk at the Mars Society conference. He's a chemist who taught at Harvard and the University of Florida, and who now runs the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution, or FfAME. Benner's sometimes controversial views included his belief that a nearly 50-year-old attempt to detect life on Mars was far more successful than generally believed.

First, congratulations. I guess, as we speak, you said you had a letter, an e-letter published in Science regarding the Viking results?

Steve Benner: Yeah, that's right. Just two days ago. It's been a 50-year story where a very small mistake in the interpretation of data from a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry instrument, the famous GC-MS, people decided that those results that they obtained in 1976 proved that martian surface had self-sterilizing soil and that life was-

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, right. Yes, the perchlorate.

Steve Benner:

Yeah. Well, that's right. Well, they didn't know about perchlorates. But in 1976, they did consider the possibility that soil had nitrates. So, for all of your listeners who know, have made gunpowder as a small boy, you know if you mix potassium nitrate with carbon, charcoal, organics, you get gunpowder. So, Klaus Biemann did worry about whether the nitrate in the soil had burned all of his organics before he had a chance to see them, because the very first thing he does is heats it up to 500 degrees centigrade, and that's gunpowder. But he didn't think about perchlorate. And so, perchlorate is at room temperature innocuous. It's a salt, doesn't do anything. But you could dry it out, you heat it up to 500 degrees centigrade, getting ready to put it into an instrument to detect your organic molecules. You set them on fire. And you make what Biemann saw, which is methyl chloride and methylene dichloride, which are the perchlorate oxidation products of the organics.

And so, they actually showed that the soil contained organics, but they misinterpreted the results as [inaudible 00:32:23]. And then the mistake was that Biemann writes it all out, that we teach students they should always look at the original literature. Don't look at the reviews. Don't go see what somebody else said about what somebody said. Go talk to the guy directly. So, Biemann in his first paper was quite clear. He said, "We didn't see methyl chloride on the flight out. It might be indigenous to Mars." In fact, it is. And in fact, had he just been a little bit more clever or someone had just poked perchlorate at him, he would have said, "Oh, yeah, that's it." He would have had the aha moment.

Mat Kaplan: Because there was this interpretation that "Oh, these must have been," you said, "solvents, cleaning fluids that contaminated the experiments," except that they didn't, apparently.

Steve Benner:

Exactly. So, that is a mistake that is in 1976, 50 years ago, and we finally got two days ago an e-letter into Science. Dirk Schulze-Makuch is in Germany, Jan Špaček, a number of us co-authored this, where we basically said, "This is the mistake that led to Horowitz, in his review in Scientific American, miscalling a gas that boils at -26 centigrade, and it's a gas, it's not a cleaning solvent, he called it a cleaning solvent." And from then you can watch in the literature as the people read the review articles and then the reviews of the reviews, but never the original literature. They did not understand that in fact the soil was not self-sterilizing.

And this poisoned... Well, for 20 years, there was no missions to Mars. NASA shut down the program. Gerry Soffen, who directed the Viking mission, said, "Hey, that's the ballgame. No organics, no life." Of course, it was not until 1996 when this Allan Hills meteorite came along from Antarctica, which came originally from Mars with these small-

Mat Kaplan: ALH84001.

Steve Benner: There you go. Absolutely. And that was the thing that got Dan Golden being summoned to Bill Clinton's office, the Oval Office. And apparently, Clinton had books from the Library of Congress on Mars all over the floor of the desk.

Mat Kaplan: Wow.

Steve Benner: And so, he says, "Is this life or isn't it?" And Golden says, "I don't know." And then Clinton says, "Why the hell are we paying you? I mean, you're supposed to tell me if we get invaded by little green men. What to do about it?" But Golden was a brilliant administrator. He had served for both Republican and Democrat. He knew how to raise money. And so he managed to secure 20 years of the NASA Astrobiology Institute. And that's one of the reasons why we have Perseverance on the surface of Mars today seeing the vivianite organic complex, which is the strongest sign we have by far of there having been life 3.5 billion years ago.

Mat Kaplan: And it's your belief that we can be reasonably confident that not only was there past life on Mars but likely it's still kicking around.

Steve Benner: Well, we use the preponderance of evidence, more likely than not. This is when you go to court. You're not going to be put in jail. This is a civil lawsuit. You have to have more evidence in favor than opposed. It's not proof beyond a reasonable doubt, not proof beyond a shadow of a doubt. But yes, absolutely. There's no question that I can come up with non-biological experiments for a few of the results that were... non-biological mechanisms to give a small number of the Viking results. But they're all consistent and taken together with the lifestyle that I would expect for a autotroph living in a resource-scarce environment, having access to solar energy, but very limited in terms of the water it has access to and very limited in terms of the reduction potential, the electrons that it has access to.

Mat Kaplan: So an autotroph being an organism that makes on its own what it needs to stay alive.

Steve Benner: That's right. So a plant is an autotroph. You're a heterotroph because you eat plants and you eat animals who have eaten plants, but absolutely. An autotroph is able to take carbon dioxide and make what we like to call the reduced carbon, the carbohydrates, the sugars, the amino acids, and all the other things that you need to put together into biology.

Mat Kaplan:

So, microbes may have adapted for life on Mars, but humans will need much more protection, including protection provided by the places they call home. Award-winning architect Melodie Yashar is another longtime acquaintance. I've watched her and her teams make tremendous progress in the creation of 3D-printed habitats and other structures, including a massive Mars analog habitat at NASA's Johnson Space Center. Formerly of the George Washington University and ICON, Melodie now leads a startup called Inara, where she continues to expand this exciting technology, not just for Mars, but for solving housing challenges on our own planet.

Where are we compared to where we were with the work that you do, this additive construction, particularly using locally sourced materials, ISRU? Where are we compared to 10 or 15 years ago and compared to where we need to be if we're going to live in these things on Mars?

Melodie Yashar: Oh, what a great question. I think that we're much further than we used to be 10 or 15 years ago. The fact of the matter is that there are more additively manufactured structures here on Earth today than there ever have been in prior history. And there are more jurisdictions interested in permitting these structures for occupancy here on Earth than ever before. There's great interest in the technology. There's great interest in the resilience of the system to be fireproof, hurricane proof. And this is proving in my current work to be a huge value-add for the technology and how we can address post-fire Altadena, how we can address the Gulf Coast of Texas and other areas that have been inflicted by natural disasters. And so, there's not only great interest in, of course, the future applications of this construction technology for space but also in the short term here on Earth.

Mat Kaplan: When I attend a conference like this, a space conference, there's very little of interest to my wife. But when I tell her about the work that you are doing, she gets very excited because of the potential for this, not just potential anymore, as you've just described, for what can be done down here on Earth, terrestrially. And she particularly thinks for underserved populations and Third World nations.

Melodie Yashar: Yes. There is a huge interest. And we've always, myself and others who are working in the additive construction industry, have always spoken about the potential of introducing rapid growth within the housing sector to serve the people that need it most. And that's really what it comes down to, is that we're lowering the cost of construction and the time it takes to build so that we're not limited to actually create the solutions that are most needed in our cities. There's a lot of talk of technology being disruptive, taking jobs away, et cetera. But the thing about additive and the thing about construction in particular is that without those solutions, we don't have a way of actually introducing housing and other types of infrastructure, frankly, that can be realized affordably. That's just the thing that we run into time and time again. So, not only is this a disruptive technology for space but also for in the short term here on Earth. That's why I find it so provocative. That's why I find it so powerful.

Mat Kaplan: We've never built a structure on another world. The only ones we've ever built anywhere beyond the surface of Earth are space stations, International Space Station, now the Chinese space station. It does seem like there's so much left to do. But it's what you're looking forward to.

Melodie Yashar: It's what I'm looking forward to. I feel like we've got to start somewhere. And if we can introduce value in the short term here on Earth for people and communities and in areas that need more resilient construction technology, then I think we're doing our job in addressing our current concerns, but also thinking ahead to how these systems will deploy on Mars.

Mat Kaplan: I'd be proud to have one of your roofs over my head, Melodie. Thank you. It's always fun to talk with you.

Melodie Yashar: Thank you, Mat. I appreciate it.

Mat Kaplan:

We'll close, well, almost close, with the current leader of the Mars Society. James Burk has been a space and Mars geek for many years. He first joined a Mars analog mission in 2011. And in 2023, he commanded a joint US and French analog Mars mission at the Society's Mars Desert Research Station. By that time, he had become the Mars Society's executive director.

James, I am so glad I could make it up here today. My only regret is that I will miss the third and final day of this year's conference of the Mars Society, but it has been a fascinating and very stimulating couple of days.

James Burk: It's been a fantastic event. Our lineup of speakers this year at USC has been great. And our attendance has been up over last year. Having it in LA, I think, is a great idea.

Mat Kaplan: There's a lot going on at the Mars Society. You opened the conference the first day, gave us a little rundown of all the stuff that you guys are up to. I'm going to start, selfishly, with the work that you have done with our organization, The Planetary Society, just in the last year or last few months, including the Day of Action, where you guys collaborated with us and about 18 other organizations for that terrific day in Washington, D.C.

James Burk: I opened my remarks about that yesterday with the idea that the symbol in Chinese for crisis is the same as opportunity. And that's what this is, is an opportunity to forge new strong partnerships with Planetary Society and other organizations like that, because this is the time we all need to rally to help our friends at NASA and our friends in the science community.

Mat Kaplan: Obviously, this is something that the Mars Society, under your leadership, this is something you want to do even more of, this advocacy work in the Capitol?

James Burk: We have been gearing up to do more advocacy work. We've been growing our US chapters for the last year in preparation for it and mobilizing them to talk to their local Congress people, both at home and in D.C. We had several members that came and participated in the Day of Action with Planetary Society. And we hope to do more events like that in the future and help amplify the campaign that we're all working on together.

Mat Kaplan: And it was great to see our director of space policy, Casey Dreier. He was on that terrific panel with the one and only Bob Zubrin last night and Tiffany Vora. Great people, three terrific spokespeople. I want to hear about some of the things that are unique to the Mars Society that you went through, including the now three, count them three, analog Mars stations.

James Burk: Yes. I mean, there's a whole global community of analog research stations. We got that field going in 2001 when we built the Flashline Arctic Station. And we've had much success in Utah with our Mars Desert Research Station. Over 315 crews, 2,000 crew members in the last 22 years. 4 of those have reached space. We hope many more in the future will.

Mat Kaplan: That's a pretty cool record. All right. The newest one is in Kashmir in India?

James Burk: That's correct. The HOPE Station, which stands for Himalayan Outpost for Planetary Exploration, is our new station in partnership with Protoplanet and the Mars Society of Australia. And the first crew just finished up there last month. It's a new station. It's in a high-altitude lake in Ladakh, Kashmir. Very scientifically interesting. And we are going to be working with them over the next few years to grow that program, select crews. We plan to have three to four crews per year operating primarily in the summer. And it's a fantastic opportunity for the science community to participate in Mars analog research in a unique environment that's scientifically interesting.

Mat Kaplan: Fascinating. Someday, someday, I've been threatening to apply for years, but hasn't happened yet. Something else you guys are up to, which you did talk about, is this Mars Technology Institute, which, to me, sounded like a cross between NASA's NIAC, NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts, and a little bit like our STEP Grant program. But tell me about that.

James Burk: So, we started the Mars Technology Institute two years ago after Robert wrote his most recent book, The New World on Mars, which talks about what the economy on Mars would be like. It would be an inventor's economy where you're exporting IP back to Earth in return for support and supplies. And so, we all thought, "Why don't we just start this now on Earth?" And so, we are putting together an incubator accelerator program to start companies that will help us settle Mars but also have dual-use technologies that can be commercialized here on Earth for products and services immediately.

Mat Kaplan: And I want to recommend the book, which is why we had Dr. Zubrin on The Planetary Society Book Club talking about it. It's fascinating. There's an amazing innovation on just about every page of the book. There's much more we could talk about, but I want to close with mention of your chapter system, something that we don't have at The Planetary Society.

James Burk: We have a global system of chapters around the world. We're in 50 countries. And in the US, we have about two dozen chapters that are active, that are meeting regularly, working on projects together, going to space events, organizing and talking to their community about humans to Mars. And this is an important part of the Mars Society. It's how we've refurbished our spacesuits at the MDRS over the years. A chapter took the lead on that. It's how we organize our conferences. Often the chapter at the local university that we have the conference at helps out. And our international chapters as well have all kinds of projects that are interesting that they work on. And so, we're sort of an independent, loosely bound organization that's swimming in the same direction of trying to get humans to Mars.

Mat Kaplan: Like us, and we're all doing it in our own way. Thank you for this advocacy work, for the partnership that you're building with The Planetary Society as well, and just for this conference as well. It really has been a blast.

James Burk: Thank you so much. I'm so glad you were able to come, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: There's one more participant I want you to meet. I don't think he was the youngest person at the Mars Society conference, but I believe he was the youngest presenter.

Sasha: I go by Sasha. I'm from Vancouver, B.C., Canada. And I am 13 years old as of 24 hours ago.

Mat Kaplan: Wow. Happy birthday, Sasha.

Sasha: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Is this part of your birthday present, getting to come down here from British Columbia?

Sasha: Yes, definitely.

Mat Kaplan: You asked a couple of questions. You got a really nice compliment from the head of the robotic Mars Exploration Program at JPL. That's a pretty cool thing, too.

Sasha: Yeah, that was good. I mean, it just kind of feels great to get that kind of a compliment from a person of that kind of status in this industry. And yeah, it just feels pretty good.

Mat Kaplan: Why in particular did you want to come down here to the Mars Society conference? I know you're also making a presentation, you said.

Sasha: Yeah. So, this is my third year, my second year presenting. I believe it was Robert Zubrin who came up to me and asked if I would like to present next year, and I said, "Sure." And so, here I am. And I'm very excited, too. I'm presenting on youth involvement in space exploration. Gee, a 13-year-old talking about youth involvement in space exploration.

Mat Kaplan: Sounds perfect. Is Mars in your future? Space science, space engineering?

Sasha: I personally feel like if I'm going to go into any industry, it's probably going to be the computer industry. I really like information technology and that kind of sector, because computers are really the future, and there's so much application in every sector from robotics to space exploration. But I love just being here and being around all these people that are really a lot smarter than me, believe it or not. And it's quite an experience. Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know how many people here are a lot smarter than you, Sasha, but it's great to have you here as part of the conference. And good luck with your presentation.

Sasha: Actually, that's a funny thing that you say because someone just came up to me, and they said, "What are you studying?" And I had to explain to them, "Oh, I just got into grade 8. I've just started high school."

Mat Kaplan: Got a ways to go.

Sasha: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: And who knows where you'll end up. Thanks very much for taking a couple minutes to talk to us.

Sasha: Yeah. Thank you. Thank you very much.

Mat Kaplan: Meeting young space enthusiasts like Sasha may have been the most inspiring experience I had at this year's Mars Society conference. I'm grateful to the Society for allowing me to meet him and so many of the other participants. They give me hope for our future on the Red Planet and for all of us down here on the pale blue dot. For Planetary Radio and The Planetary Society, I'm Mat Kaplan.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Before we end our episode, there's one more Mars topic that we need to talk about, something that came up more than once during the conference, perchlorates. While they're part of what makes Mars such a fascinating chemical world, they also pose a serious challenge for human explorers. Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, has more in What's Up.

Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hello, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So, this week, talking about another one of Mat Kaplan's wild adventures.

Bruce Betts: Oh, that man, he is the worst at retiring I've ever met.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I feel like I'd be the same way, though. If I ever retire someday as a millennial, I'll go to all the science conferences. It'll be my whole life. But while he was there, several of the people that he spoke with brought up perchlorates in the martian soil. And it's something that comes up in almost every Mars-related episode. But very rarely does anyone ever explain what are perchlorates and when did we discover them on Mars. Why is this such a big deal?

Bruce Betts:

All right. Perchlorates are salts. Here's a great definition. Salts that contain the perchlorate ion, which is one chlorine and four oxygen, so chlorine, ClO−4. It was suspected way back with Viking, but the first to actually find it and determine that's what it was was the Phoenix lander in 2008, which detected perchlorates in the soil. And so, the implications of this is that, one, it can give false results or confusing results to things like the Viking GC-MS, gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer, and other things. Viking mission, basically, it's a really heavy-duty oxidizer. So it does things that you might think life was doing.

But on the flip side, somehow, it's actually really not very healthy for most life. I don't actually play with it because, well, it blocks the iodine uptake. It competes with iodine for the sodium/iodide symporter in the thyroid, which is a little tiny train that's in the thyroid, I think. I'm not sure. Anyway, it's bad. It's bad hoodoo for humans. So, it's also something if you send humans someday, you have to wonder, worry about it. But also, there's just the oxidizing. And, I mean, we knew Mars is red, for God's sake. It's got an oxidizer. And this turns out to be at least one of the things that has rusted all of that iron on the surface. So it wasn't like a shock, but there is a lot of it, and it does have these weird implications.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. I remember first learning about it years ago when I was talking with someone at Griffith Observatory about their work trying to study perchlorate-eating bacteria, extremophiles. And I-

Bruce Betts: Whoa.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, that sounds like exactly the kind of thing that we need to be studying in order to figure out how to grapple with this issue on Mars. But thankfully, we've got some time to figure it out before we send humans.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. There are a few other issues to work out. That one, not the top of the list, probably. Yep. Would you like to hear something, a little something?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Little something.

Bruce Betts: Something a little... Random Space. Rewind. And it's a Random Space effect, rewind, because it's worth hearing again from the distant past of Random Space Facts. You ever notice how the Earth's moon is always showing the same face to Earth, basically? Did you ever notice that? That's shocking that you would notice that. That's very impressive. And so, if you're on the other side of the moon, you would have no idea that the Earth is there from just looking up, if that's the only place you'd been. Well, Pluto and its moon Charon are both tidally locked, so they show the same face to each other all the time throughout their orbits. So someone on the far side of Pluto or the far side of Charon would not know, at least not from visual clues, that they're in a close orbital configuration with the other. So, because of the similarity in sizes and gravities and the distance, they actually both synced up rather than the Earth being the much more dominant body. So, the moon's synced up to please Earth and show fealty.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, that's got to be a really weird thing. I mean, I know no one has ever stood on Pluto or Charon on the far sides, as far as we know, to figure that out. But how weird would that be, just be completely out of the loop that you were right next to this other body in space?

Bruce Betts: Heck of a surprise when you wandered across the dividing line, like, "What the-"

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right? "What is that?" No, actually, for the 10-year anniversary of the New Horizons flyby of Pluto, I wrote a cute little song called Locked in Love about Pluto and Charon.

Bruce Betts: Oh my gosh, that's fabulous.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I actually did.

Bruce Betts: We did a Random Space Fact video where we spun a child. Oh, I didn't do it. It was Emily Lakdawalla and her actual child. So it's okay to demonstrate tidal locking. But writing a song, wow. Can you sing it for us?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Not right now. Maybe some other time.

Bruce Betts: Okay. I'll try to remember to ask again. All right, everybody. Go out there, look up the night sky, and think about... I just can't stop thinking about Sarah singing a song about tidal locking in love. Thank you, and goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with more space science and exploration. If you love this show, you can get Planetary Radio t-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email, [email protected]. Or, if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app.

Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our Mars-loving members from all over the world. You can join us as we continue to advocate for missions like Mars Sample Return at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Casey Dreier is the host of our monthly Space Policy Edition. And Mat Kaplan hosts our monthly Book Club Edition. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. My name is Sarah Al-Ahmed, the host and producer of Planetary Radio. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth