Planetary Radio • Jun 24, 2020

China on the Final Frontier

On This Episode

Andrew Jones

Contributing editor for The Planetary Society

Jason Davis

Senior Editor for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Low Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars, even Neptune and the edge of the solar system--China’s ambitious plans for space exploration and development are laid out by Planetary Society contributing editor and Chinese space program expert Andrew Jones. Jason Davis provides a brief overview of what’s in the June Solstice edition of The Planetary Report, now available for free. And it’s time to give away ice cream on What’s Up!

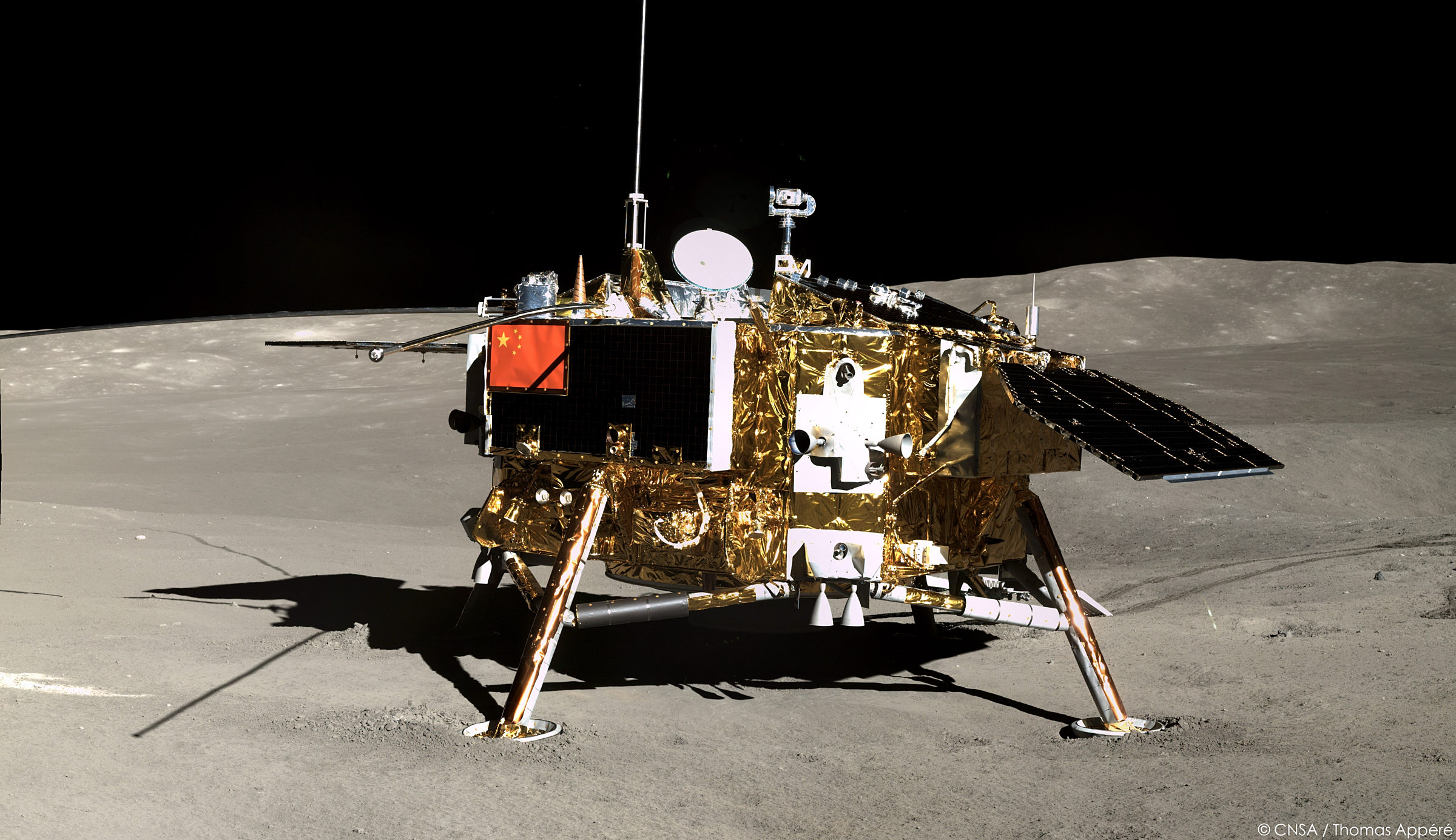

Yutu-2 rolls across the surface This video shows China's Yutu-2 rover rolling across the lunar surface after its initial deployment from Chang'e-4.Video: CNSA / CLEP

Related Links

- Contributing Editor Andrew Jones

- Your Guide to the July Mars Launches

- China Considers Voyager-like Mission to Interstellar Space

- June Solstice edition of The Planetary Report

- The Downlink

- Asteroid Day

Trivia Contest

This week's prizes:

A Planetary Radio t-shirt!

This week's question:

Create and share your LightSail joke! Mat and Bruce will judge submissions based on their entirely subjective and often juvenile senses of humor. Special extended deadline is 8 July 2020, so no excuses!

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, July 8th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

An ancient Greek analog computer used to predict planetary motions was retrieved from the sea in 1901. It dates from somewhere between 87 BCE and 205 BCE. What was this relic called?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the June 10 space trivia contest:

What was the last flight or mission of an astronaut who had been in the Apollo program, and who was that astronaut?

Answer:

Vance Brand was the last Apollo program astronaut to go into space. He did so in 1990 on the STS-35 mission. Brand had previously been part of the Apollo-Soyuz mission.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: China and the Final Frontier, this week on Planetary Radio. Welcome, I'm Mat Kaplan of the Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. Andrew Jones is back. Our treasured contributing editor will share all of the challenges China has taken on from a space station in low Earth orbit to beyond Pluto. Well, not everything, because as you will hear from Andrew, the middle kingdom has far more underway than we have time for. We'll also visit with Jason Davis, the society's Editorial Director introduces the June Solstice Edition of the Planetary Report. Later on, one of you is going to win delicious ice cream and a spoon to eat it with. What more could you ask for? Well, how about Asteroid Day? It arrives on the 30th of June, just as it does every year, but the celebration is already underway. Our boss, the Science Guy, is part of it. You can learn more at asteroidday.org. Remember, the planet you save may be your own.

Mat Kaplan: Speaking of celebrations, if you are catching this week's plan [rad 00:01:13] right away, you might still be able to join Bill Nye, Bruce Betts, Jennifer Vaughn, LightSail Project Manager, Dave Spencer, and me, as we mark a year of sailing on the light of the sun. The live webcast starts Thursday, June 25 at 4PM Pacific Time, 11PM UT. You can register free at planetary.org through the link to the LightSail Extended Mission Coverage. The show will be available on-demand soon after. Just time for one headline from the latest edition of The Downlink, a NASA rover called Viper will head for the moon's south pole next year hitching a ride on an Astrobotic lander.

Mat Kaplan: Some of you remember my conversation with Astrobotic CEO, John Thorton, last August. There is much more waiting for you at planetary.org/downlink, including NASA's appeal to citizen scientists who want to help Curiosity drive across Mars. Jason Davis is one of those who makes sure the Downlink is available every week. He is also behind the award-winning quarterly magazine from the Planetary Society, and he's ready to take us into the brand-new edition. Jason, beautiful edition of the Planetary Report, so congrats and thanks to you and everybody else on our team who worked on this. I guess the centerpiece, and it is very appropriate, is this pictures of Earth article, which is loaded with these remarkable images of Earth, which are just stare-worthy. There's a new term. You told me moments ago that it might not have been this planet that got the focus this quarter.

Jason Davis: Yeah, when we were doing our long-term planning for what was going to be in this issue, we had initially wanted to feature Mars because we knew it was going to come out right now, like mid to late June, and of course next month we have three new Mars missions launching and that's very exciting and we're going to be talking a lot about that. But because this is a print magazine, we planned the content a couple of months ahead of time, so we were doing the initial planning of the Mars feature in March, and that was the time the pandemic was really ramping up.

Jason Davis: We didn't know, it was in many ways, we still don't know we're here in June, how bad it was going to get, exactly what life was going to look like in two months when this magazine came out. We didn't want to just drop a giant Mars issue without acknowledging what was going on in the world today. Of course now, since then, we have more going on in the world today with all the things happening surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement. But yes, we decided let's swap out the Mars feature, we can put that online, and we have. If you go to planetary.org/Mars2020, we got all our Mars content there. Instead, we were like, let's just feature some pretty pictures of Earth from space, that's one of our favorite things to do here at the planetary site anyway, so I hope our readers enjoyed the pictures. We sure had fun picking them out.

Mat Kaplan: I sure am enjoying them. From this first ... you could barely even call it monochrome image from a surveyor moon lander of Earth. It's just gorgeous and it includes very appropriately the pale blue dot image from 1990 Voyager 1, which seems even more appropriate in light of those other incentives that you were talking about. The other main piece in this, I guess, is this nice article by our colleague, Planetary evangelist, Emily, about sample return.

Jason Davis: Yeah. We went ahead and ran her sample return roundup article as planned for our second feature. This is a look at all the different sample return missions that are in progress. It's remarkable what is going on right now in terms of bringing samples back. We have Japan's Hayabusa 2 spacecraft, which is on its way back to Earth right, believe it's December, it's still on schedule to return those samples. We have Osiris Rex, which is going to be collecting its first sample a little later this year. Perseverance, NASA's Perseverance rover is launching to Mars next month, and that'll be the first step in bringing a sample back from Mars. The fourth mission is China's Chang'e 5. That's going to land on the near side of the moon and bring a sample back to Earth. The last we heard, I believe that's now shifted to early next year, but anyway, an exciting time if you're a scientist or someone who's interested in studying rocks from other places in the solar system.

Mat Kaplan: Stay tuned for a second mention of Chang'e 5 from our main guest this week, Andrew Jones, when we talk to him about the Chinese space program in a moment. There is so much more in this edition of the Planetary Report all available to everyone for free in digital format at planetary.org. Of course, members of the Planetary Society will receive the printed version, which is in my hot little hands right now. There's just one more thing to mention here, because it's so touching to see this, and it's a page by Carl Sagan. Not the first time it's been in the Planetary Report.

Jason Davis: Yeah. We have an essay from the September '96 issue by Carl describing why Mars, that's the title of the article, Why Mars? It's interesting. We've been building out a lot of new resources on our website explaining why we're so interested in destinations like Mars. That's a question we've asked ourselves a lot and preparing some of these new materials is why go to Mars the first place? What's the motivation? What are we trying to discover? What are scientists trying to learn? Looking back, here we have this great essay from Carl himself laying out the reasons why Mars exploration is important, so I hope readers enjoy that little look back as well.

Mat Kaplan: His arguments hold up very well, and of course, he describes them as only Carl could. It's introduced by, I don't think you ever got to work with her, but Charlene Anderson, the original Associate Director of the Planetary Society. It's great to see her byline once again in the Planetary Report, the magazine that she was responsible for for many, many years. Thank you for the preview, Jason. I hope folks will take a look, it's well worth it.

Jason Davis: Thanks, Mat, always fun to be here.

Mat Kaplan: If there's a single lesson to learn from my recent conversation with Andrew Jones, it's that no one should doubt China's determination to explore the solar system and develop space resources. Andrew's network of resources and contacts often reveals more about Chinese plans and projects than you can hear anywhere else, including from China's various agencies and organizations that are part of its progress. It's all the more amazing that he is able to do this work from his home outside Helsinki in Finland. I caught him there a few days ago between assignments for the Planetary Society Space News and others.

Mat Kaplan: Andrew, welcome back to Planetary Radio. I'm sorry to say it has been a little bit over a year since we last checked in with you about what's going on with the Chinese space program. I think it's probably safe to say there is a lot going on, it has been and more to come. Once again, welcome.

Andrew Jones: Thanks very much, Mat. It's great to be back. Yeah, indeed. As you say, it's about a year and a bit, and it feels like a decade [inaudible 00:08:36] in space and loads going on.

Mat Kaplan: Let's start, because it's so timely, with a question about the recent success of Demo 2, the Crew Dragon mission that carried those two astronauts to the ISS where they're going to be living for the next number of weeks. Did this generate any reaction in China that that you're aware of?

Andrew Jones: I don't think there was any official reaction in the sense of the Foreign Ministry, for example. I don't think I saw any question posed to them with which they'd give an answer. However, some of the space organization such as the China Human Spaceflight Agency, they ran some articles in Chinese explaining in great depth what was going on and how important this was. I think there was a lot of people following in China. It did generate a lot of interest but not an official reaction, if that makes any sense.

Mat Kaplan: I read something from you though about possibly three private companies in China, I assume, who want to launch astronauts much as Space X is now successfully done.

Andrew Jones: That's right. China now has this nascent but very active commercial sector, which involves some private companies. Some of these companies are involved in developing their own launch vehicles. Now, from what I saw, there were at least three of these who stated that, as well as actually getting to orbit first, they are looking long term into launching astronauts. That's something which is very much what the state-run space programs take care of. This would probably be tourism-related. There were a number companies, I think, ispace was one, Galactic Energy another, and another called Space Trek.

Mat Kaplan: Ah!

Andrew Jones: Yeah. They've really taken the inspiration from someone. They've stated that, yes, they're working on light to medium lift launch vehicles but also have an interest in sending astronauts into space. Those comments started appearing around the time of this mission. While I say there wasn't an official reaction to the Demo 2 mission, it's actually because of SpaceX and other companies that China has taken the decision to open up its space sector to private investment and private companies.

Andrew Jones: Back in late 2014, there was a government decision that the small satellites sector and launch vehicle sector could be opened to this other activity. That's because they noticed what was going on with SpaceX, Blue Origin, Planet Labs. While reusability is probably one thing which everyone looks at and think, "Wow!", these countries are going to have to catch up with SpaceX in America. It's more than that. There are launch companies which gets a lot of attention in China in what they're doing, and certainly, it's very exciting to follow these. But it's also about creating new supply chains, about lowering costs and driving innovation in the way in which the state-run space sector wasn't able to do or wouldn't be efficiently able to do. What we're seeing in China with this new activity is very much inspired by the success of US space policy and efforts to commercialize space activities.

Mat Kaplan: That's quite fascinating. The parallels between the rise of commercial cargo and crew in the United States, and now on to getting things to the moon. I guess Elon can take some credit for what's happening over there.

Andrew Jones: Absolutely. I've spoken to some of these people involved in these companies. They were watching these companies, and as soon as the chance was available, they were like, "Okay. We're going to leave our jobs at these state-owned space enterprises and start our own initiatives." Yeah, absolutely. In the next few months, Galactic Energy, which is one of the newer, second wave of launch vehicle companies, they're going to attempt their first orbital launch with a solid rocket. That's going to be called Series 1, so that's something to look out for. There's been three companies in China, which attempted to reach orbit. The first two was Landspace and OneSpace failed, but ispace last July succeeded.

Andrew Jones: Speaking of ispace and LandSpace, they're two companies to watch out for because they are developing liquid methane and liquid oxygen launch vehicles just like Blue Origin and SpaceX are. They are looking to launch maybe in the first half of next year, so we might see Chinese companies with the first methalox rockets, which would be quite something. They've started a long way behind but in some aspects, in some respects, they're able to catch up even though they're going to be light to medium lift launch vehicles.

Mat Kaplan: I was only in China once. I may have mentioned this to you before, it was back in 1988, almost prehistoric in terms of the developments that have taken place there. One of the impressions that I was left with is how amazingly entrepreneurial the Chinese people are at every level. Whether it's at the level of a street vendor or apparently were now seen in the area of commercial space development. Do you see that?

Andrew Jones: I think that's an observation a lot of people will take from a visit to China. In the West, we have a lot of preconceptions about what China would be like from the coverage that we receive and so on. To actually go there is quite something else.

Mat Kaplan: It's exactly right. I couldn't agree more. I want to go back, except that the next time I think I want to go with you.

Andrew Jones: Okay, yeah. We have to do that.

Mat Kaplan: Let's turn away, at least for a little while, because we're going to come back to Earth orbit and look toward Mars. Of course, we have been providing lots of coverage of what is coming up this summer. We have given China some attention with its mission, which will be launching in that same window as Perseverance, the former 2020 Mars rover from NASA. Tell us about this very ambitious trip that China hopes to make to Mars.

Andrew Jones: Well, this is going to be a very big step for China in its space ambitions. While NASA makes these Mars landings seem almost quotidian, that would be 26 months or something, NASA has been tremendously successful. But this is going to be a big challenge in a number of ways for China. If we go back to, I think it was 2011, China actually had a first Mars probe launched, and that was piggybacking on the Russian Phobos-Grunt mission, which was, it was aiming at least to collect samples from Phobos and bring them back to Earth, which would have been a tremendous mission. Unfortunately, it didn't leave Earth orbit and re-entered within a month or something.

Andrew Jones: We're nine years down the line and China is now in a position to actually launch its own mission. They've developed a new heavy lift launch vehicle, which will be launching this mission. They have grand stations, which will be capable of supporting deep space missions, not just in China but then they have support in Argentina and Namibia. They've landed on the moon twice, once in the far side, so they've gained experience in propulsion and carrying out these maneuvers away from the Earth. Also just in terms of developing spacecraft and the [GNC 00:16:09] and everything is needed. They've had to adapt the parachute technology, which they developed for the Shangzhou human spaceflight missions to help slow down a spacecraft making an entry into the Martian atmosphere.

Andrew Jones: There's many different aspects and China's really made big developments over the last decade, and now they're ready to make his mission. They have engineering goals, simply getting to Mars, getting an orbiter into orbit, and then attempting the entry, descent and landing, which is the hardest part. Also something not to be taken for granted but also developing the science expertise, developing human expertise to manage these missions and carry them out. All of these big efforts, big endeavors in their own ranks, so China's putting all these together.

Andrew Jones: The latest on the mission is that in April they gave a name to the mission, which will be called Tianwen-1, which means asking the heavens, which comes from a poem from a famous ancient poet called Tianwen. This will be the first mission in a larger planetary exploration of China as it's called. The spacecraft was delivered, I think, in April, March or April to the Wenchang space launch center in southern China, and the launch vehicle, the Long March 5 was delivered, I think it was 23rd or 24th of May. China hasn't actually said when they're going to launch. We're assuming the launch window is going to be similar to Perseverance launch window.

Andrew Jones: Based on previous activity, the Long March 5 has taken about two months to get ready before launch, so 2-month launch campaign. Looking at the date that that arrived, we're looking at around July 23 maybe, the launch, depending on whether and how things go. It's secretive. Not all the details are out, but slowly, slowly learning.

Mat Kaplan: That's my guest, Andrew Jones. Still ahead is his description of a proposed Chinese mission that may follow in the footsteps of Voyager. We'll be right back.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here, CEO of the Planetary Society. Even with everything going on in our world right now, I know that a positive future is ahead of us. Space exploration is an inherently optimistic enterprise. An active space program raises expectations and fosters collective hope. As part of the Planetary Society team, you can help kickstart the most exciting time for US space exploration since the moon landings. With the upcoming election only months away, our time to act is now. You can make a gift to support our work, visit planetary.org/advocacy. Your financial contribution will help us tell the next administration and every member of Congress how the US space program benefits their constituents and the world. Then you can sign the petitions to Pres. Trump and presumptive nominee Biden and let them know that you vote for space exploration. Go to planetary.org/advocacy today. Thank you. Let's change the world.

Mat Kaplan: That rocket, the Long March 5, that has literally been a long march toward getting this rocket functional again hasn't it?

Andrew Jones: Absolutely. This Long March 5 is China's largest launch vehicle by far. It depended on developing new propulsion, so China developed kerolox rocket engines to power this. This was a project which was started in the 2000 and suffered a few delays. I think it was late 2016 when there was the first mission, which wasn't completely smooth but successful. However, the next launch in July 2017 failed to reach orbit. There was a problem with one of the first stage engines and the rocket failed to reach orbital velocity and the mission was lost. Actually, discovering what the issue was took a long time. It turned out there was a turbopump issue and I think they went through at least two rounds of attempting to fix this problem. They were apparently close to sending a Long March 5 to the launch center early in 2019, and then another issue was found so they're back to the drawing board.

Andrew Jones: But I think it was over 900 days between the second Long March 5 failure and getting the third Long March 5 in late December 2019 to actually get it back on the pad and get it flying. Now, fortunately for China, that mission went very well, and that opened up two possibilities immediately. The one would be the Mars mission, which they had planned since 2016 to launch in 2020. If the Long March 5 failed in December then we wouldn't be talking about this Mars mission. The other thing is that it allowed them to test a varied Long March 5B, which is designed to send modules of around 20, 22 metric tons to low-Earth orbit. This mission went ahead in May and was successful, meaning that China can now, probably in early 2021, start launching the modules for its planned modular space station.

Mat Kaplan: That is going to be quite an accomplishment. Before we go on, you said kerolox, does that mean kerosene and liquid oxygen?

Andrew Jones: It does, yes.

Mat Kaplan: Okay, just wanted to clarify. How did the Long March 5 and the 5B, how do those compare with, let's say, the space launch system, that super heavylift vehicle that the United States is slowly developing?

Andrew Jones: Yeah. The Long March 5 is much smaller. I think it would be comparable to, in terms of payload capacity, it's comparable to say the Atlas V or the Delta IV Heavy.

Mat Kaplan: Ah, okay, got it. But big enough, obviously, because getting 20 or 22 metric tons at a time up into low Earth orbit is pretty impressive. Let's follow up with that space station. It is an ambitious plan and, aren't they hoping for international involvement just like the other one that is literally called the International Space Station?

Andrew Jones: Yes. There is a level of international cooperation already, so China's embarking on this project of its own because it is excluded from the ISS. China initially in 1992 when it decided to launch a human spaceflight project, its envisaged constructing a small space station on its own in low Earth orbit. However, there was the impression that having demonstrated in 2003 onwards that China could launch astronauts itself that perhaps it could gain entry into the ISS program. However, that didn't happen, so China's going alone with this space station, however, in cooperation with the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs, there was a call for international experiments to fly to the space station. This will probably take place after the construction is finished on 2023, 2024 probably. But there was a number of experiments, I think around 17, if I remember correctly, experiments from around the world, Europe, Africa, and elsewhere, which will be part of a first round missions. This is similar to what Japan did with its kiboCube in terms of hosting missions from other countries.

Mat Kaplan: Have you heard any discussion of possibly international astronauts or taikonauts going to this new space station?

Andrew Jones: I have. There's two different possible activities which have been mentioned. The first is that, and this has been known for quite a few years, that a number of European space agency astronauts are learning Chinese. A couple of these, Matthias Maurer and Samantha Cristoforetti, they actually went to China to participate in sea survival training two, three years ago. They've been working closely occasionally, I should say, doing exchanges in terms of astronaut training and so on. The idea would be that sometime well after the space stations been established maybe at the end of this decade, around that, one or two ESA astronauts could make a visit to the Chinese space station. That's something that both sides are looking at and it would take some years to iron out all the details, but that's something that we're looking at.

Andrew Jones: The other thing that's been mentioned, but seems much more speculative is Pakistan stated that it was aiming to send an astronaut, a Pakistani astronaut, on a Chinese mission. But that's something I've only heard from the Pakistan side and haven't seen it confirmed by the Chinese side, but that's another thing to look for because China has its Elton Road project.

Mat Kaplan: Yes.

Andrew Jones: Which has various commercial and geopolitical ramifications, so that could be something that they would look to in the future perhaps.

Mat Kaplan: So interesting.

Andrew Jones: The other thing that's worth noting about, this Long March 5B missions. Primarily, they were looking to verify that this rocket can launch these 20-ton payloads to low Earth orbit. What they use is an analog payload for a Chinese space station module. It was actually a prototype of a new generation crewed spacecraft, so this was uncrewed test flight for a new spacecraft, which will have two different variants. One would be for low-Earth orbit, which could take 6 to 7 astronauts to the space station. The other, and this is the one they tested, would be larger and would be capable of traveling to the moon and back, so being able to handle the harsher radiation environment, and also the much more energetic re-entry coming back from the moon much faster than you would as you do from Leo.

Andrew Jones: That was apparently very successful, so this new heatshielding, which they developed worked as far as we can tell. They handled something like 3000°C during the re-entry, so that is an indication of, not just China's plans to send astronauts to low-Earth orbit, but also looking further ahead actually going to the moon.

Mat Kaplan: I am not a bit surprised. How interesting? It sounds like this new capsule, this new spaceship has elements of both Crew Dragon and the Boeing CST100 Star liner and NASA's Orion, which has yet to carry humans. We're still hoping that'll happen next year in 2021. The word fascinating just keeps coming back. You have brought us back to the moon and China is continuing its notable successes there with robotic exploration. Chang'e 3, Chang'e 4, still active. The Yutu 2 rover just woke up again, didn't it? For another day of work on the moon, one of those two-week long days.

Andrew Jones: It's apparently now Lunar Day 19, which is very hard to get my head around. It seemed like a few weeks ago that this thing actually landed in Von Karman crater. Yeah, it's been a tremendous success. I think they were at a lifetime of three Earth months for the rover, and now, well over a year and 1/2, I think, around about now, 500 days. The lander had a design lifetime of one year and that's still going strong, and so are its science payloads as far as we can tell. But I think that's not actually a surprise, because Chang'e 3 lander, that still wakes up apparently. There amateur or radio enthusiasts who pick pick up the signals from Chang'e 3 still. When did this launch? Late 2013 and it's still going? If you go on Twitter and search for Chang'e 3, you'll see that these guys are picking up signals showing that it's still going. It's quite amazing to think that that's still running.

Mat Kaplan: It sure is. What's next for China on the moon?

Andrew Jones: Next up, and this is assuming that the Mars mission goes well, I think between October, December, the next mission for the Long March 5 will be the Chang'e 5 mission, which is going to be a very complex and very ambitious mission to collect samples from the moon and bring them back to Earth. This is the next stage in the Chinese lunar exploration program. What this is going to do is collect, I think they're aiming for between 1 and 2 kilograms of samples from, I think the site is near Mons Rumker in Oceanus Procellarum. This is going to be the first sample return since the 1970s. Of course, the Apollo missions brought back a tremendous amount of lunar material.

Andrew Jones: The Russian Lunar missions, I think the last one was 1976, that brought back material as well. That mission involved a direct [inaudible 00:30:02] so the spacecraft landed, scooped up some material, and headed straight back to Earth. The Chang'e 5 mission is going to be more complex. It's going to involve landing on the moon, and then scooping up the material into an [ascent 00:30:17] vehicle and that is going then to head back into lunar orbit and rendezvous with the service module before coming back to the Earth. Then, there will be a transfer to a return capsule and service module will release that before arriving at the Earth.

Andrew Jones: What we're looking at there, it's like a practice of the Apollo mission profile. It looks like "Okay, they want to do a lunar sample return, which obviously has tremendous scientific value, but also looks like it's practicing again for eventually, maybe in the 2030s, sending astronauts to the moon and bringing them back." That mission is going to be very, very interesting.

Mat Kaplan: I'll say. Before we finish, I cannot resist bringing up something else that I discovered in your writing, and that was just a brief mention that China has successfully tested, or a company in China maybe successfully tested, a drag sail. I had to bring it up because, of course, it came up on our last week's show while we talked about LightSail. Dave Spencer, the project manager for White Sail 2, mentioned this concept of a drag sail and how it may be useful in de-orbiting satellites in Earth orbit. Can you tell us a little bit about this test, and what it may mean for China and commercial development, possibly, but I guess beyond that?

Andrew Jones: I can talk about it, but only briefly because there's so much going on that I was basically, I was able to scan this article which was [protect 00:31:57] by a company called SpaceTY, which is based in Hunan province in China. They're a private company, which is somewhat, I don't know if attached is the right word, to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, personnel came from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and put some satellite expertise. At the moment, they don't have their own constellation plans, but what they do is providing services to customers. A lot of there satellites are technology verification satellites. This one was, I think, [Chaoshan 1 00:32:31] Rocket 03. One part of the mission was to deploy a small drag sail to increase the surface area of the spacecraft and lower the density, and basically take some of the orbital lifetime from the spacecraft.

Andrew Jones: According to this article, which is in Chinese, but there are lots of data showing what they've done and how, why they think this is successful and all the different variables including several activity which they've taken into consideration. It seems like one hand, that there are commercial companies in China who are interested in these kinds of technologies. Also, they did ... this same company did a collaborative test with a French startup, which they were testing solid iodine thrusters, which can be used for station keeping then de-orbiting as well, so that can reduce lifetime. This tells us that there's companies in China who are looking at these kinds of issues considering the issue of space debris very seriously, which is good because I think the Starlink satellites that SpaceX have been putting up, they've been getting a lot of attention in terms of the effect on astronomy, the effect on debris in Leo. But there are a lot of Chinese companies which have plans to launch 5G constellations or remote-sensing constellations, involving lots of satellites. This is also being considered in China I think this is good news.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, our crowded skies becoming ever more crowded, particularly with these new constellations. Let's wrap up with a review, an update on something that you wrote about for the Planetary Society back in November 2019, and it is impossible to read about this mission, at least the mission proposal by China, without thinking of Voyager 1 and 2. Tell us about this.

Andrew Jones: This is November. I'm trying to think that's like a decade ago considering the things going on. Yes, there's a proposal, in which, I think it was Peking University, the PI, or one of the project leaders or one of the project advocates perhaps has laid out a plan to send to probes, one to the head of the solar system, and one to the tail. The idea would be to examine the helio [inaudible 00:35:09] and the termination shock, and these different parts of the solar system and answer a number of questions which have been raised by Voyager missions and other observations, and just to follow-up and bring more understanding. It involves magnetometers. There was something about, not cosmic rays but something called anomalous cosmic rays, which was somehow particles being accelerated when they enter the solar system.

Andrew Jones: Seriously, writing the article was really eye-opening because there's so much going on at the edge of the solar system where you would think there is nothing, but yeah, it's fascinating. This would involve a number of flybys, so unlike the Voyagers, there is no grand tour possibilities because that was taking advantage of lineup with the planets, which only happens every century and a half or something like this. However, one plan they had within this vision for the mission was a Neptune flyby, and release on an impact on observing. I was going to say the impact to the impact, but I can't say that, and observing what happens when the small impact interacts with the Neptunian atmosphere.

Andrew Jones: They're trying to get as much as they can out of this proposal. As I understand, this is still a proposal but John often works in something called 5-year plans, so next year we may find out whether or not this mission gets to go ahead. The fact that this has been talked about somewhat is a good sign. The other mission, which I think has had a bit of a boost in terms of an announcement from the China National Space Administration was this asteroid sample return and comet flyby, which is tentatively called Zheng He, after, was it 14th century admiral. That is another very fascinating and complex mission which China is looking to carry out. Without even going into the other plans China has for the south pole of the moon starting maybe 2023, 2024, there's so much going on, big ambitions and lots of complexity. Really, it's a very exciting time to follow what's going on with China.

Mat Kaplan: Which is proof that we should check in with you more frequently, I think, Andrew. We didn't mention it, this mission, which is currently being considered to the edge of the heliosphere, the termination shock, is the interstellar heliosphere probe, and two of them, IHP1 and 2, like Voyager 1 and 2 even though these are going to go on opposite directions, I also saw that you noted just by coincidence, if the spacecraft launch when they hope to launch them when everything lines up properly, I think 2024 your piece said, they would reach about 100 AU, astronomical units from Earth, at just about the time of the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic in 2049. Pure coincidence.

Andrew Jones: Maybe helpful for your mission proposal, yes.

Mat Kaplan: Andrew, this has been delightful and eye-opening. We really must do this again. I'm going to look for cheap airfare to China, so that we can make our trip there. Seriously, I have wanted for years to go there. If it could be done, then give us some entrée to at least some of what China is up to in low-Earth orbit and beyond because it is up to a lot as you've made clear, and it would be a very exciting trip.

Andrew Jones: Absolutely, that would be fascinating. Yeah, I think we could pick a conference or maybe at this new coastal launch sites, they have a Hilton Hotel, which overlooks the launch site. If you can time things well, you can maybe book yourself into the hotel around by the time something interesting would be up.

Mat Kaplan: All right, it's a date. Andrew, thanks again. Thank you for sharing your expertise and I'm so glad that you are monitoring all of this for all of us at the Planetary Society and Planetary Radio and the other outlets that you share this with.

Andrew Jones: Thanks, Mat. It's a pleasure and an honor to to chat with you and to just talk about space.

Mat Kaplan: It's fun isn't it. That's what makes my job so fun, getting to talk to folks like you. Andrew Jones, he is a contributing editor for the Planetary Society. You can read his stuff at planetary.org, but he also writes for Space news, an absolutely wonderful outlet that does so many great space experts write for us, space journalists. He's based in Finland, and that's where we talked to him today at his home outside of Helsinki. He tweets a lot from at Ajay_FI. Highly recommended.

Mat Kaplan: Time for what's up on Planetary Radio. Bruce Betts is the chief scientist to the Planetary Society. If you were listening last week, you also know that he's the program manager for our LightSail program. But he's back just to look up at the night sky and all the other fun stuff we do at the end of the show this week. Welcome! Do you remember two weeks ago you talked about Vanguard 1, oldest human-made object in space?

Bruce Betts: Still in space, yes.

Mat Kaplan: Exactly. Patrick Wiggins, actually, a NASA JPL solar system ambassador in Utah, that program the JPL runs, he says Bruce was one third right. Also up there is the third stage of the rocket that put Vanguard 1 in orbit along with what is called a piece of debris that is associated with the launch. He says, "By the way, since Vanguard 1 and its third stage can get as bright as magnitude 10, they could be seen with pretty small telescopes", and he even, Patrick included images that he had gotten of them going across the sky. He adds, "Great job as always on the podcast." Thanks, Patrick.

Bruce Betts: That's a good point, and I try to say the oldest human-made spacecraft, but I got sloppy sometimes. Good point, space junk, cool.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, but you weren't wrong, that's the important thing.

Bruce Betts: I'm never wrong.

Mat Kaplan: I know.

Bruce Betts: I'm just temporarily off the perfect line.

Mat Kaplan: What's not wrong about the night sky?

Bruce Betts: There is so much not wrong about the night sky. In the evening sky, coming up at around the 11PM, 2300 time, we've got Jupiter and Saturn. Jupiter looking really bright over there in the East, brighter than any of the stars, and Saturn hanging out to its left, looking bright and yellowish. July 4, they will be lined up nicely with the moon, and July 5 the moon will be between them, a nearly full moon will make a lovely site. In a couple of hours later, Mars comes up in the East as things I want to do looking reddish and brightening over time. In the pre-dawn East, we've got Venus looking super bright.

Bruce Betts: Interesting thing to look for over the next few weeks is the brightest star in Taurus, Aldebaran, is below Venus right now. Venus is still quite low to the horizon, so you need a pretty clear view but you can also ... if you get that view, see Aldebaran, the two of them will close and get closer over the next couple of weeks and then switch places. Now, Aldebaran, although a bright star, Venus is still about 100 times brighter.

Mat Kaplan: Good fireworks coming for the 4th of July.

Bruce Betts: Yes. On to this week in space history, we have quite the mix of things. Let's start with remembering the Soyuz 11 crew who passed away in 1971 during re-entry from their mission. Going back to 1908, the Tunguska impact or exploded over Tunguska in Siberia. As far as we know, did not kill any humans, but sure could have because it leveled the forest the size of, about one and a half times the size of the city of Los Angeles.

Mat Kaplan: Wow!

Bruce Betts: Do you remember that? With asteroid day and asteroid week, we've got a lot of materials on our website. Go to planetary.org/defense, if you are interested in learning more. Then in 1995, STS71, special mission to the first docking of the space shuttle with the Mir space station. The first docking sentence Apollo-Soyuz about 20 years before that, which we may discuss momentarily. We move on to Random Space Fact.

Mat Kaplan: That's not wrong.

Bruce Betts: Apologies to those who may have seen this on my social media for Father's Day, but I thought it was so interesting I'd bring it back. The first father and son to both have flown in space were cosmonauts, Alexander and Sergey Volkov. What I find particular interesting is on his first mission, Sergey, the son, returned to Earth from the International Space Station with the second son of a space traveler to fly in space, space tourist Richard Garriott, son of astronaut, Owen Garriott, and they came back on the same Soyuz after Sergey Volkov had been up in space for several months, and Garrett a few days as a space tourist.

Mat Kaplan: That is so interesting. I did not see that in your social media, and of course, I would've said the Garriotts, I did not know about this cosmonaut pair.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it was close. Both Alexander and Serge had long careers doing all sorts. Serge commanding, being on multiple expeditions to the International Space Station.

Mat Kaplan: Speaking of astronauts with long careers, let's go to the contest.

Bruce Betts: All right. I ask you, what was the last spaceflight of an astronaut who had been an astronaut in the Apollo program, and who was that astronaut, and why did I keep using the word astronaut over and over again? I didn't ask you that part, just the other part. How did we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: You did specify in the Apollo program, you said nothing about him going to the moon. Ian Jackson in Germany. "Tricky question from Bruce this week. Maybe he was feeling mean since you scarfed all the ice cream."

Bruce Betts: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: That was two weeks ago. Well, only, and I think this may be a new record low, only about 20% or so of entrance in this contest got it right.

Bruce Betts: Wow!

Mat Kaplan: Isn't that something? Here's the winner. John Guyton in Australia, another Australian listener and winner to the program, although he's a first-time winner as far as I can tell. John says that, he actually asked, "Was it Vance D. Brand on STS35? He was in the Apollo program, but didn't fly until Apollo-Soyuz", Bruce?

Bruce Betts: Yes. That would be the answer I was looking for, Vance Brand flying in 1990 on STS35 Columbia as the commander that mission. He flew on Apollo-Soyuz and three shuttle flights and was, depending on where we go in this discussion, the only Apollo astronaut to fly post-Challenger.

Mat Kaplan: Did you hear that? I'm sure that I could hear thousands of head slaps, forehead slaps.

Bruce Betts: Donor yourself out there.

Mat Kaplan: Why was I eating ice cream two weeks ago? Because John has won himself that coupon for a pint of Ben & Jerry's ice cream. I hope it's good in Australia. They have Ben & Jerry's there, I hope it's exported. Anyway, he might want to try Boots on the Moon. Moon, that terrific flavor inspired by the Netflix series, Space Force, which I'm still watching and enjoying. I haven't made it all the way through. And a Space Force spoon, at least you can enjoy the spoon, John, if you can't get the ice cream. Seems a shame though, that would be a shame.

Mat Kaplan: Devon O'Rourke. "Brand was born in Colorado, another Coloradan represented in space, love it." You might be able to tell Devon's from Colorado. This from Bob Clane in Arizona nearby, who was among those, the 80% who got it wrong, but he's added, "Do I get bonus points for knowing that John Glenn was the last Mercury astronaut to fly? Do I get extra bonus points for knowing that John Young was the last Gemini astronaut to fly? Do I get even more bonus points for knowing how to spell Mat correctly?"

Bruce Betts: No, no and yes.

Mat Kaplan: Good, good because I'm going to give him 15,000 bonus points for getting my name right.

Bruce Betts: I saw he's really feeling spirited, I'll give you bonus points, three for each of the other answers.

Mat Kaplan: Okay. All right. We can move on.

Bruce Betts: I remember, I forgot to discuss this with you, Mat, but what do you think of this question? Something a little different? Makeup a LightSail joke.

Mat Kaplan: Why not?

Bruce Betts: I figured Mat and I would, we'd judge it on humor. I will probably look for a lack of egregious technical errors other than a proper humorous context and whatever else crosses our mind, but that's it, make up a LightSail joke. Go to planetary.org/radiocontest, you good with that, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: I am just fine with that. This kind of question, getting people to be creative, long overdue in my opinion. You've got some time to come up with your LightSail joke. In fact, you have until July 8 at 8AM Pacific Time to get us this answer and win yourself, how about a Planetary Radio T-shirt? Why not?

Bruce Betts: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: We haven't done one in a while. It's that beautiful design from Chop shop, and you can go to chopshopstore.com or planetary.org/store, I think it is. Anyway, that's where the Planetary Society store is, and you can see that shirt and all of our other great merch.

Bruce Betts: I had a question. Are you going to mail the ice cream to Australia?

Mat Kaplan: They got it to me, as I mentioned, with dry ice and that worked, but I'm guessing because the Planetary Society is just a poor, non-profit and we ship by Sea Turtle overseas.

Bruce Betts: That's true. Depends on currents when you actually receive it.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. The dry ice might be uncomfortable for the sea turtle, anyway.

Bruce Betts: They have a shell. No, we don't want to take any chances.

Mat Kaplan: We'll just send a coupon instead.

Bruce Betts: All right. In a fit of lack of creativity, hey everybody, go out there look up the night sky and think about sea turtles and ice cream. Thank you and good night.

Mat Kaplan: I bet those are two terms that have never ever been spoken together before, sea turtles and ice cream. I guess maybe there's mock, at Ben & Jerry's mock turtle ice cream flavor.

Bruce Betts: Good one.

Mat Kaplan: He is Bruce Betts, the chief scientist to Planetary Society. You probably know he joins us every week here for what's up. Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its members who celebrate all spacefaring nations. Can you join us? Visit planetary.org/membership to learn how. Mark Hilverda, our associate producer, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. Stay safe and well, Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth