Planetary Radio • Jul 18, 2025

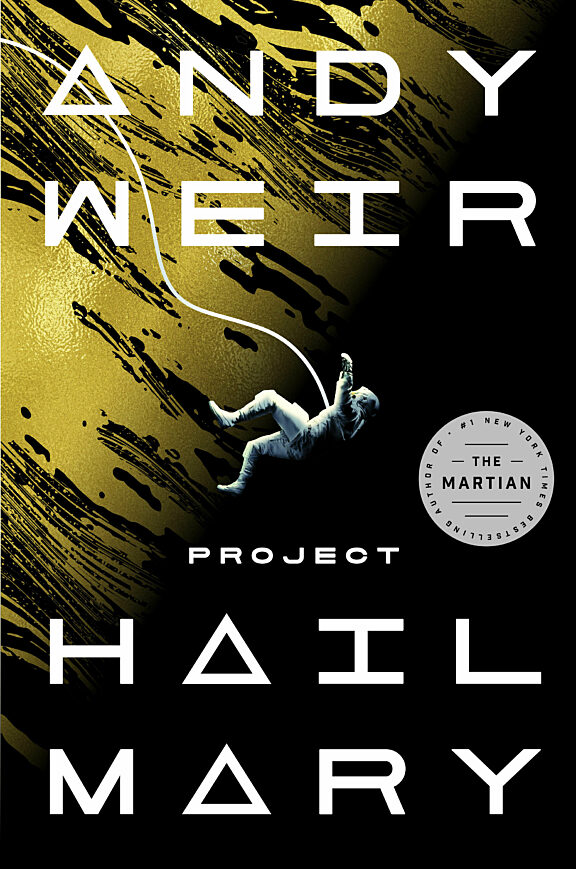

Book Club Edition: Andy Weir and Project Hail Mary

On This Episode

Andy Weir

Author of The Martian and Project Hail Mary

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Author Andy Weir was as shocked as anyone when The Martian became a top bestseller novel in the US. He repeated that achievement with his equally mind-blowing science fiction masterpiece Project Hail Mary. Former Planetary Radio host Mat Kaplan welcomed Andy in April of 2023 for the first livestreamed author conversation in The Planetary Society's member book club. Now, with the film version of Project Hail Mary approaching, we’re proud to begin making these insider interviews available to Planetary Radio listeners. We’ll post them on the third Friday of each month. Join us as we talk with Andy about his obsession with getting the science right while his reluctant and unlikely hero attempts to save humanity from a deep space scourge.

Live Q&A with "Project Hail Mary" author Andy Weir Mat Kaplan interviews Andy Weir about "Project Hail Mary" for The Planetary Society's first Book Club LIVE virtual event.

Related Links

- Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir

- Planetary Radio: Author Andy Weir and Project Hail Mary

- Planetary Radio: A Conversation with Andy Weir of “The Martian”

- Planetary Radio: Andy Weir’s New Novel Puts a City on the Moon

- Planetary Radio: One Last Blast: Author of 'The Martian' Andy Weir with JPL Chief Engineer Rob Manning

- Planetfest ’21: To Mars and Back Again

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Planetary Society Member Community

Transcript

Mat Kaplan:

Hello Planetary Radio fans. I'm Mat Kaplan, senior communications advisor at The Planetary Society. If you've been listening to our show for a while, you may remember that I created and hosted Planetary Radio for its first 20 years. There was something I wanted to do during that entire time, but could never find time for. It was only after handing the show over to Sarah Al-Ahmed that I could start work on a Planetary Society Book Club with great support from my colleagues and especially digital community manager Ambre Trujillo. We premiered the club in the spring of 2023. I wanted to start big, so our first selection was Project Hail Mary, the terrific bestseller from our friend Andy Weir, author of The Martian. After a month of book discussions in our member community, I invited Andy to join me for a live conversation. Now, with the premiere of the project Hail Mary movie approaching, we couldn't imagine a better way to begin adding these book club live streams to the Plan Rad feed than a reprise of that show with Andy.

We'll post another of these book conversations on the third Friday of each month. By the way, you can also enjoy the original video live streams on our website. You'll find them and much more at planetary.org/video. It helps to have read the book of course, but we think you'll enjoy them regardless. Project Hail Mary is the largely first person tale told by a very unlikely hero, one who very reluctantly ends up the only hope for the survival of humanity. As always, and as you'll hear right from the start, Andy goes to enormous lengths to make sure he gets the science right. I'll warn you that there are some spoilers in the conversation you're about to hear. So with great gratitude to Sarah, here's my very, very fun conversation with Andy Weir presented live on April 27th, 2023.

Hello everybody. Welcome to this first climactic moment in the book club here in the member community. Thank you everybody for first of all, making all of this possible, being a member of The Planetary Society, but also for joining in this little experiment, this book club that we've wanted to create for years now. It's been on my to-do list, I mean literally on my to-do list. Okay, so the first thing I wanted to say is that you are famous for the almost endless research that you do as you are putting together a book.

Andy Weir: I do way too much.

Mat Kaplan: I want you to... Do you have that spreadsheet handy?

Andy Weir: I do. I do. I have it here.

Mat Kaplan: If you read stuff that is science-based, when you're reading an Andy Weir book, this is the kind of work that is behind it. Now, this is in addition to him talking to all of his wonderful friends across the science and engineering communities, but I'm looking at it now. Tell us what we see here.

Andy Weir: This page is all about the math behind the biology of an Astrophage. So everything that's in orange is a physical constant. Everything that's in yellow is an input value, and everything that's in gray is just calculation and blue or answers. So for instance, this is where... This part here is where I worked out what the critical temperature of Astrophage is. It is the temperature that Astrophage needs to be in order to function. The way Astrophage works is it turns heat energy into neutrinos and uses those neutrinos as stored mass. Okay.

Mat Kaplan: Through some form of magic that we don't understand.

Andy Weir: Through some hand wavy magic that I made up. Yeah. However I figured out... And the way it turns out is basically what happens is two protons will collide and the kinetic energy of that collision will turn into two neutrinos going opposite directions. So the protons are still there, it's just the kinetic energy that they had of the collision. Some of that kinetic energy gets turned into neutrinos.

Mat Kaplan: [inaudible 00:04:34] would be so proud.

Andy Weir: Yes. And so the question is how much kinetic energy is the minimum? What is the absolute minimum amount of kinetic energy necessary to make two neutrinos? Well, it's the mass energy of two neutrinos. I mean, you probably can't read the detailed numbers, but-

Mat Kaplan: Actually, I can. Yeah, I can make it up.

Andy Weir: That's the collision energy, there it is in an electron volts. This is a calculation of... You work out how much energy is necessary in that collision. Then you say, okay, so what is the velocity that two protons would have to have in order to collide and have that much kinetic energy in their collision? It works out to be about 3000 meters per second is how fast they have to be going. And so the average velocity of particles in a gas or liquid or whatever defines its temperature. So I figured, okay, so at what temperature is the average velocity equal to that collision velocity? And it turns out to be 369 Kelvins, which is 96 °C.

Mat Kaplan: There we are.

Andy Weir: And there we are. So that's the temperature that Astrophage is. If the temperature is below 96 °C inside the Astrophage, it will not be able to generate neutrinos, and so it needs to expend energy to maintain its heat. If it's above 96 degrees, if there's energy going into it and it's above 96 degrees, it will create neutrinos until the kinetic energy of the protons inside goes down to that level.

Mat Kaplan: And then you give it an infrared source to look at and it runs your spaceship to another star.

Andy Weir: Right. So this whole section is how quickly an Astrophage gains energy by being on the surface of the sun. This part is how fast a fully enriched Astrophage will ultimately get to by expending all those neutrinos as velocity. So it's about 0.92 C. This is how much energy an Astrophage loses in watts as it's just out in deep space due to black body radiation because it is this temperature and this temperature is ultimately defines how much energy... Your temperature defines how much energy you lose if you're out in space.

Mat Kaplan: I get it. Stay with us people.

Andy Weir: Yeah. And then this is velocity that Astrophage loses leaving a solar system. This is how much resistance it runs into from atoms in the interstellar medium and so on. This is the wavelength of the photon that'll be created by annihilating two neutrinos. So that is a mass conversion again, of those two neutrinos into two photons, which have to be going opposite directions for everything to work out, but then they get mirrored in the same direction, which makes a wavelength of 25.984 microns, which is in the book the Petrova frequency. So all of these things were determined by this spreadsheet. And that's just a spreadsheet for Astrophage.

Mat Kaplan: Can you just-

Andy Weir: This is the spreadsheet for calculating things related to the Hail Mary itself. That one's-

Mat Kaplan: I want to see the rocky muscles tab.

Andy Weir: Right there. So this is how muscles in an iridium work. So this is how much force they can generate. It works like a piston. This is how far a piston, there's a bunch of stuff. This is how much water you need to have in the muscles. This is how many calories, food calories worth is consumed by a single expansion of the muscle.

Mat Kaplan: Isaac Asimov is spinning in his grave.

Andy Weir: Why? He should be happy.

Mat Kaplan: Well, with pride. He's spinning with pride because we are his progeny, especially you are. Listen, let me throw some questions, start throwing some questions at you, and we're going to get to the new ones. These are people who were thinking about this days or weeks ago. From Jean Lewin, who happens to be one of our poets for Planetary Radio. Hi, Jean. A question for Andy, what other iterations of Alien life forms did you consider before coming up with Rocky? Also, he saw the wonderful pop culture references in the book and a sly one about, Hey, Rocky, watch me pull.

Andy Weir: Watch me pull. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. How did you come up with this wonderful life form?

Andy Weir: Technically, the question was, Mat, inaccurate fun is not fun. Technically, the question was, what other ideas did I have? And the answer is none. Basically, I came up with Rocky slowly over time, and I took my time designing how this life form would be, and then I did it from the ground up. So I actually started by selecting a star, and that's 40 Eridani, and that's a real star to be the home world. And if anybody here hasn't read Project Hail Mary, well, you're going to get all the spoilers-

Mat Kaplan: They're out of luck. They have more than a month. They have more than a month.

Andy Weir: Yeah. But so we learn toward the end of the book that life on both Rocky's species and all... Both Rocky's home world and [inaudible 00:09:39], were seeded with life by a panspermia event from Tau Ceti. Life did not initially evolve on Earth or on Rocky's home world. It evolved on what they end up calling the planet Adrian in the Tau Ceti system. And that evolved a distant ancestor of Astrophage, which was another interstellar life form that would travel from star to star, ended up seeding both Earth and Rocky's home world. As a result of this, Rocky's home world, which the main character calls Erid, E-R-I-D. It is life very much like us. They have DNA, they have mitochondria, they have the mechanisms of the cell. So it's not like silicon-based life. It wasn't a separate genesis.

Mat Kaplan: And they have liquid water, they have water anyway, but it's-

Andy Weir:

As a result of this... Well, I had to go one step at a time here. I decided on a panspermia event, which means this life has to have liquid water because it's not silicon-based or anything like that. It is, you need liquid water for the life the way that we do it on this planet. So I needed a solar analog star. You can't really have life like ours around a brown dwarf or a red giant or anything like that. You think it gives up too much radiation. The home world has to have certain minerals. So really the best way to do it is to use another mean sequence star in the same place as ours. In other words, a solar analog. 40 Eridani is a star very much like the sun. And so is Tau Ceti, by the way. So within the fictional context of the story, what it is it's not so much that 40 Eridani is like the sun. It's that 40 Eridani and the sun are both like Tau Ceti, which is where the life evolved.

So anyway, so I said, all right, I'm going to use 40 Eridani, now I need a planet. So I looked at the planets and I chose 40 Eridani A, which is the first planet. It is the closest planet to the star because that's the only one that had any hope. The other ones are either too far away or too small, or they're gas giants or whatever, and they just have no hope of having a ground-based life form like I wanted to have. So the first planet in, it's about eight times the mass of Earth. And so this is a real exoplanet.

And so I modeled the home world after this real exoplanet, and I said like, okay, it's eight times the mass of Earth. I'm going to arbitrarily assume that it has the same density as Earth because we don't know which would make it have about 2G's on the surface, okay, so it's more gravity. And then I'm like, it is really close to the star. It is absurdly close to the star. It's going to be hot as hell there. And I'm like, but we need liquid water. So the only way you can have an extremely high temperature, but still have liquid water, is to have an extremely high atmospheric pressure. So I'm like, okay. So they have a really thick atmosphere. It happens. Venus has a thick atmosphere. So I'm like, all right. So they have a really thick atmosphere and they have liquid water and oceans and all that.

But when you're that close to a star, if you have a really thick atmosphere, the star is going to sandblast it all away. You're not going to keep your atmosphere for very long. That's what happened to Mars. That's what happened to Mercury. And so I'm like, why does this planet that is just making out with the star, it's closer to its star than Mercury is to ours. It's just right up in the star's face. How has this planet not had its atmosphere just completely blown off by the star over the last several billion years? And I decided the answer is it has an incredibly strong magnetic field. It makes Earth's magnetic field look like a refrigerator magnet. And I'm like, okay, so how do you get a strong magnetic field? It's like, well, you have a liquid metal core and you spin. That's what Earth does.

And so I decided this planet has a whopping magnetic field. It's already got a nice big metal core because it's eight times the mass of earth. And I said, okay, the only variable I have left is how fast it spins. So this planet whips around, the length of their day is six hours long. The whole planet spins around every six hours, which makes an incredibly strong magnetic field. So that's how they keep their atmosphere. So you see bit by bit, I'm putting together the environment that they evolved in. And so once I had that, then I could start putting together the species. And so I'm like, what kind of creatures could live in a... I decided 29 atmospheres, 210 degrees Celsius on the surface, on average, atmosphere is so thick that light doesn't reach the surface.

So as a result of that, there's no need to evolve vision. And then the obvious question is I'm like, well, wait a minute. Why is there a biosphere on the surface at all? Because if light can't get there, how's the energy getting there? And I decided, oh, okay. It's like an ocean. There's airborne microbial life. That is where the sunlight gets. And then things below that, eat that, things below that, eat that. And then there's a whole biosphere on the surface that relies on the food trickling down from above

Mat Kaplan: Life finds a way.

Andy Weir: Finds a way. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Andy Weir: So anyway, all these things... And that's what I came up with. And I've always been sick of the sci-fi trope of, oh, we meet an alien and they're totally comfortable in our atmosphere, pressure, and they breathe air and they eat the same food as we do. And it's like, no, this is like we have completely incompatible environments. Rocky will die if he enters Ryland's environment and vice versa. In fact, they do a little bit and get real close to dying.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Yeah. Rocky's almost gone. Yeah. So Ryland, in the beginning of the book, one of the things we learned is that he has written this paper that goes against the thinking that, oh, we really should be looking for life as we know it. Water- Go ahead.

Andy Weir: Yeah. Ryland wrote that paper because that's an opinion I've always had. I've always thought the Goldilocks zone was stupid. It's like, oh, you have to be within this range, or you can't have liquid water. And I said, who says you need liquid water?

Mat Kaplan: I figured.

Andy Weir: And so I decided to put that part of myself into Ryland. And then for fun, he turns out to be wrong, or at least he never does find life that doesn't rely on liquid water, finds out Rocky's entire biosphere, relies on liquid water same as ours, because Panspermia.

Mat Kaplan: I've got another one that I should have asked you right away when we were showing off the spreadsheet, when you were showing it off. And it comes from my wonderful colleague, Sarah Al-Ahmed, who's taken over planetary radio, of course, doing a great job. She's an astrophysicist. She says, "I'm tempted to put together a guide to all of the math Ryland does at the beginning of the book." And I don't think just at the beginning of the book, and that apparently you've done as well, it'll have to include a URL that goes to your spreadsheet as well. But I think that would sell.

Andy Weir: I mean, that might be interesting. I think most of the math that you see would be way below her level. I mean, the majority of the math that Ryland does is high school algebra. Now, I did a lot of math that would be probably much more interesting to her because I had to work out, okay, what is the time dilation of a relativistic rocket, a constantly accelerating craft? The equations, I mean, I found them all online, but I had to do it, and a mass conversion fuel and so on and so forth.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. And brilliantly, as we've seen, and everybody, I don't know if you've been through the comments in the book club channel here in the member community, but people... I didn't expect anything else, but everybody was as thrilled by this book, whether they had read it previous to us making our first choice in the book club, or whether they picked it up finally. We gave them the incentive to finally get to it. I'm going to go to one... Actually a couple from Craig Griffin. At the end of the book, when Ryland is on Erid, the Eridians construct the custom keyboard with additional tonal and inflection chords, and it's pretty cool too. What a great finish. This leads me to think that they have a far more complex sound range than humans have. Every time Ryland has a conversation, he's composing a very complex musical composition. Does that, pardon the pun, resonate with you?

Andy Weir: Yes and no. Basically, Ryland becomes fluent in Iridian. And he can't make the noises physically with his own body, but he can play them on a keyboard. So it's not so much a composition, not like anything like the artistic creativity involved in a composition. If you heard this, you wouldn't think, I can dance to that. It's just sounds that are used to communicate. And of course, to Eridians, he probably sounds like someone who's speaking a very simplified version. It's like everybody here has probably had professors in college that could kind of barely speak English, and they're extremely brilliant people, but they work for that college on a research grant, and they're forced to teach a class to retain the title professor. So I imagine Ryland to Eridians would be kind of like that. He would sound like a Stephen Hawking voice to them because he's playing a synthesizer, right? And it's making noises that Eridians can understand as language, but it certainly doesn't sound like an Eridian speaking. He would very much be like a Stephen Hawking analog. He's a smart guy, but his voice is synthetic and artificially generated.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know why I didn't think of this before, but I would love to think that this certain set of notes means something in Eridian, da da da.

Andy Weir: Da, da da. Well, it probably wouldn't mean anything because all of their words and stuff are chords. And so that's a single set of singular notes. So it's kind of the same as a person humming. It's like mm mm mm. We have some words that are done with simple sounds, like I could say. Uh-huh.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. Yeah. Right.

Andy Weir: I mean, I can convey information without using phonemes. I can go like, ah, or oh, that's information that's being conveyed. But I think if [inaudible 00:19:59], would probably do Eridians sound like somebody going, [inaudible 00:20:06]. It wouldn't mean anything.

Mat Kaplan: All right, here's the other one from Craig. Living on Erid for so long in an artificial dome with nothing but some rocks and artificial light, everything outside the dome being pitch black, one must wonder how that would affect a human psychologically. This did occur to me as well, and I'm glad that it ended with him just feeling so satisfied because he loves teaching so much. So what [inaudible 00:20:34] rock creatures?

Andy Weir: Well, the idea was it's a big dome, right? So he has a lot of space to do whatever he wants in. And there's artificial lighting and stuff in the dome to do a 24-hour cycle so that he gets the external cues to his body to sleep and wake and stuff like that. But for him, what's most important is he gets to hang out with his best friend every day.

Mat Kaplan: Right. I'm going to move on to one from Robert Johanneson because it's kind of related to the speech and language one. Has anyone else wondered why Andy Weir didn't have music in the story? Earth Music, Eridian music. I would love to ask him. Well, you are, Robert.

Andy Weir: Okay.

Mat Kaplan: Rocky's species communicates with tones. They even expressed themselves by changing octaves. The Eridian C was sound, you'd think they'd have a rich history of music. My guess, he says, "Although it would've been fun, imagine Rocky and Ryland listening to classics of both worlds as they work, it wasn't needed to carry and move the story along. Maybe something to think about for the movie version."

Andy Weir: Well, I mean, I didn't catch the gender of the person asking a question, but he or she-

Mat Kaplan: Robert.

Andy Weir: Robert, so I'm going to guess male. So he's right. He's exactly right. It doesn't move the story along at all. The book was already pretty long. It's the longest book I've ever written. It's 450-ish pages, and so I definitely didn't need any additional... I mean, it's best to keep it as trim as possible. I like to keep things going. I like to keep the plot moving forward to keep the reader pulled along. My general philosophy is I imagine the reader reading my book. It's 1:00 in the morning, they're laying in bed, doing some reading before they go to sleep. And there is some point at which you start to get tired and you put the book down for the night. Where is that point? What paragraph were you on when you put the book down?

Mat Kaplan: That's sadistic.

Andy Weir: I want you to pass out with the book on your face. So I don't like slow decompression-

Mat Kaplan: Exactly what happened to me.

Andy Weir: Constant stuff. Thank you. I want constant stuff happening. So that's one part of it. So I'm really very, very focused on pace in my novels. So that's one thing. The other thing is, I definitely did think of that like, oh, you should hear some Beatles music or something like that. But the next problem is that narrating in prose, people listening to music is boring. Just trust me, there's music going on. It sounds awesome.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Before I go to some of the new questions, this is my own prerogative where I threw this out to people. Much like Mark Watney of The Martian and Jazz Bashara of Artemis, we get to enjoy the amazing cleverness of the main character in this book from nearly the first page along with his sense of humor. Let's talk about Andy's ability to create these people. Do they remind you of characters from stories by others? And I'll just mention one, Robert Wilmore, another Robert, said he nominated Johnny 5 from the Short Circuit movies, the Robot. I haven't seen them, so I can't really comment, but he also, Carl Sagan, which he says that he bets Ryland would find flattering.

Andy Weir: Yeah. So yeah, I hadn't thought of that, but actually Rocky is kind of like Johnny 5.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Yeah.

Andy Weir: Kind of, he's got the [inaudible 00:23:50]. And then I wouldn't say that Ryland is like Carl Sagan because Carl Sagan is... I mean, if I was going to come up with some adjectives for him, one of the top five adjectives I'd come up with is classy, right? He's like this understated, classy, mellow guy, right? And Ryland is not like that. He's kind of a spaz. He's kind of freaking out half the time. He just doesn't have that grace and no pun intended as much as Carl Sagan. So I wouldn't say that they're like him.

Mat Kaplan: I told you before that, particularly with Mark Watney, I think and Jazz as well, less so in this case, because of course, he's a coward until he's deep into the book. I've often seen the comparison to the analog and your characters between yours and Robert Heinlein's, who are very smart and tackle things from angles that a lot of people might not think of. And I know you're a Heinlein fan, so I hope that's flattering.

Andy Weir:

I am, yeah. I'll take that compliment. Absolutely. Although Mark Watney and Jazz Bashara are both actually just me. Mark Watney is the idealized version of me. He's all of the aspects of my personality that I like, none of the stuff that I don't like, he doesn't have any of my flaws and all the things I like about myself, he has and magnified. So I'm kind of smart. He's really smart. I'm kind of funny. He's really funny. And all of my neuroses baggage and problems, he doesn't have any of that. So he's what I wish I could become the idealized version of me. Meanwhile, Jazz Bashara, who seems like a completely different person, well, she's a different person because she's kind of like, what's left over when you delete Mark Watney from me. So she is much more like the real me, or at least more accurately.

She's more like the real me as I was when I was her age, when I was 26. Allegedly very smart, yet still makes really bad life decisions, kind of her own worst enemy. Lazy, always looking for a quicker way to do things rather than just putting in the work, really immature for her age. And so she's based on flaws. And the reason I did that was because I wanted to make a more flawed, nuanced, main character. But what I learned is that people like the idealized me a lot more than they like the real me and Jazz was kind of hard to root for because she was so much the instrument of her own problems. People are like, oh, why should I root for this person? She's just causing all these problems for herself. It's hard for me to wish her well. And so I made her too abrasive and too self-destructive. [inaudible 00:26:41].

Mat Kaplan: I kept thinking, don't do that. That's just crazy. But I liked her a lot.

Andy Weir: Well, thank you. But she is based on... Although you don't think of like, oh, a 26-year-old Saudi woman who grew up on the moon is a self-insertion character, but she really is.

Mat Kaplan: But what about Ryland Grace? Where does he fit into that spectrum?

Andy Weir:

So Ryland Grace, I consider my weakest point in writing. What I need to do the most work on is character, depth and complexity. My characters tend to be two-dimensional, in my opinion. Think of Mark Watney. People love Mark Watney, but he doesn't have any depth. In fact, he barely has any character at all. All you know about him... First off, throughout the entire book. He doesn't change at all. He undergoes no change. He's exactly the same at the end of the book as he was at the beginning. His personality didn't change despite all this stuff he went through. No character growth, none. Second off, you don't know anything about this man by the time you finish the entire book. All is he's smart and he doesn't want to die. And he's from Chicago. That's it. That's it. You don't know his hopes, his dreams. You don't know if he's got a girl back at home or a boy back at home.

You don't know. You know nothing about this man. So I'm like, I need to work on character depth. So Jazz was my next attempt to make. After that Jazz, I tried to make depth complexity. She undergoes growth, she becomes a better person, et cetera. For Ryland, it was the first time I said like, okay, I'm going to make a character and I want this person to have flaws and then maybe even a redemption arc and become a different slash better person by the end of the book. And I'm not going to base him on me. So that's the big step for me on Ryland was he's the first time I made a true protagonist out of whole cloth and not based on me.

Now, he is a lot like Mark Watney in certain problem solving ways, but frankly, I think all scientists are kind of like that when it comes to problem solving. His core personality traits are that he's kind of cowardly a little naive, and he kind of always wants to emotionally retreat to a safe place. That's why he left academia to go become a junior high school teacher because he'd be around a bunch of kids who think he's awesome and would never challenge him. And it's not because he got off on the power of that. He just wanted to be in an environment that was absolutely non-threatening.

Mat Kaplan: The other thing that he shares with Mark Watney is the humor, which I think is brilliant.

Andy Weir: Gallows humor.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. But I want to differ with what you said about Mark Watney, that he's much funnier than you. You wrote him. You created him. So obviously-

Andy Weir: Well, you can make characters funnier than you and smarter than you by remembering the fact that stuff the character comes up with in two minutes is something that might take you three weeks to research and figure out. So that's like all these things that Mark Watney's like, oh, I know I'll do this stuff. That took me weeks of research to figure out, that's how I made Mark Watney much smarter than me.

Mat Kaplan: Got it.

Andy Weir: And the same with the jokes.

Speaker 3: We'll be right back after the short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, planetary Defenders Bill Nye here. At The Planetary Society, we work to prevent the earth from getting hit with an asteroid or comet. Such an impact would have devastating effects, but we can keep it from happening.

Speaker 5:

The Planetary Society supports near-Earth object research through our Shoemaker NEO Grants. These grants provide funding for astronomers around the world to upgrade their observational facilities. Right now, there are astronomers out there finding, tracking and characterizing potentially dangerous Asteroids. Our grant winners really make a difference by providing lots of observations of the asteroid so we can figure out if it's going to hit Earth.

Asteroids big enough to destroy entire cities, still go completely undetected, which is why the work that these astronomers are doing is so critical. Your support could directly prevent us from getting hit with an asteroid. Right now, your gift and support of our grant program will be matched dollar for dollar up to $25,000.

Bill Nye: Go to planetary.org/neo to make your gift today.

Speaker 5: With your support working together, we can save the world.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. Mackenzie, Owen Hop and I will give my usual upfront apologies for getting-

Andy Weir: There's no chance you pronounce that correctly.

Mat Kaplan: How much of the science and Project Hail Mary did you know beforehand? And how did you find people to consult about the science that you didn't know? Thanks. It's got to be easier now than it was when you were piecing together The Martian, right? You didn't know people then. Now they seek you out.

Andy Weir:

True. So I knew the basics of everything I wanted to know. I have a good foundational knowledge of the science involved. But for the specifics, I had to do a ton of research. And my research was mostly just Google. People think I have just this Rolodex, that's a contact list for you younger viewers full of NASA engineers and stuff like that, ready to call. And I do. I can, but Google's faster. And I found that people in the scientific community tend to be technically skilled, so they know how to put their stuff up on a website, and they're proud of what they did. So they do put their stuff up on a website. So it's generally really easy to find that stuff online. I guess what I would say is I know enough to know what I need to go find out when I'm trying to solve these problems.

So I have a baseline knowledge. It's more than a layman's knowledge of the stuff, because space is my hobby. If your hobby is gardening, you know more about plants than the average person. If you're a gear head, you know more about cars. I'm a space dork, so I know more about space. I think this specific group of people here today are probably mostly in that camp, right? So yeah, in terms of outside experts, I did talk to a few people, though, notably... Well, they're in the acknowledgments if you want the full list at the end of the book. But my favorite one to talk about is when I was in high school, when I was in fact physics class in high school, the guy who sat right next to me and was usually my lab partner for physics was a guy named Chuck Duba. We were the same year at Livermore High School and in [inaudible 00:33:14].

And so anyway, time goes on every now and then I hear from him, stuff like that. And turns out that I ended up reconnecting with him because his wife knew the producer of The Martian and something like that. So anyway, it was cool to reconnect with him. And then it turns out that he went on to be... He is a now Dr. Charles Duba, a particle physicist who studies neutrinos and was part of the group that got the Nobel Prize for dramatically narrowing down the mass of a neutrino, right? And here I was writing a story, which those of you at the beginning of this conversation, remember heavily realized on neutrino based physics. And I was like, "Hey, Chuck, can we talk on the phone for a minute? I got some neutrino question for you."

Mat Kaplan: I was smiling from the start of that because you've mentioned him before. And it's what terrific serendipity.

Andy Weir: What a random coincidence that we lab partners in. And then I'm like, actually, I do need to talk to someone who knows about neutrinos, and Chuck Duba knows about neutrinos.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Chuck.

Andy Weir: Thank you, Chuck.

Mat Kaplan: I got one from Kay Gilbert, who is one of our most faithful listeners to Planetary Radio for many years. We've kind of covered this, but maybe you'll have some more to add. I was gobsmacked that you made Ryland Grace, a Hail Mary full of grace joke, she says, A coward, couldn't help it.

Andy Weir: I couldn't help it. I'm sorry.

Mat Kaplan: A coward who had to be forced onto the flight. What made you go there? And even though he didn't remember the beforehand, why was his character during the mission fundamentally different from beforehand?

Andy Weir: I wanted to kind of subvert the trope of the just completely willing sacrifice. I wanted to set you up to think that's what happened. And then I also wanted... I seeded it throughout the book, you see evidence that he's kind of a coward, right? First off, we talked about this before, his backstory where he fled academia and all that stuff like that. Also in the book, when he's faced with scary moments, he freaks out. The first time he gets [inaudible 00:35:27], he pukes, or he almost pukes, I think. He just panics.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. It's not in the spacesuit. Yeah.

Andy Weir:

Right. He manages to not puke in the spacesuit. And then also, when he first sees Rocky's claw, he nopes the hell out of that. He's like, I'm out of here. And then he goes like, okay, okay, okay, hang on. I got to talk to this guy. So I dropped hints that he was a bit of a fraidy cat. I guess I just wanted to subvert that trope because it's all a little too easy when the main character is so noble, he's happily willing to sacrifice his life. And I thought there were two things I want to do. One, I wanted to subvert the trope. Two, I had established through the whole thing that Ryland was a coward or scared a lot, and I was planning his arc to see, to be we all where he finally makes the brave decision, which he does do. But originally, I planned for his brave decision to be when he volunteers to go on the mission.

But I thought, wouldn't it be cool if that brave decision had to happen later? And at the same time, I was looking for something to really cement in what Stratt's personality is like. And so she's absolutely the sort of person to be like, yeah, you're going, sorry. And so, yeah, Stratt was the most fun character.

Mat Kaplan: She was brilliant.

Andy Weir: Somebody who accepts absolutely zero BS on any given topic. She's just like, wouldn't we all have that kind of authority.

Mat Kaplan: As Bill Nye says all the time, she was just trying to save the world. She was just trying to save the world. So you told me once that one of your rules was never tell a story using flashbacks, and then you did. But it's so-

Andy Weir: I'm a hypocrite. I'm a massive hypocrite.

Mat Kaplan: But the structure is so great. To me, and apparently to everybody else out there, it works great.

Andy Weir:

Thanks. Yeah. The reason I say never tell a story with flashbacks is because I hate being a consumer who's experiencing a story with flashbacks in it. Because oftentimes the flashbacks are used as just a drawer to put character development in. So we've got an interesting story, and then we do some flashback to how this guy met his wife or something. Then back to the interesting plot development, then another flashback to some other thing, and it always annoyed me because it would halt the forward progress of a story when the flashback happens. And I'm like, I get why you're doing a flashback, because that means you spend less total time in exposition. Because you don't need to put the shoe leather together to connect it to the story, but it's still really annoying.

It's like when you're out there playing with your friends and your mom calls you in to come do some chores, it's not fun. It's like, I don't want to do that. So I figured this story, what I have in mind would be really, really stupid if told serially. It would be like, okay, we start at the beginning, the whole last phase stuff happens. All of this is having gigantic time jumps randomly. We go forward. Now it's four months later, now it's a year later. Now it's two years later. Now it's six months later, whatever. And it would be just really like this wild whirlwind for the first third of the book, and then they'd launched the Hail Mary, and then you would never see any of those characters again, except Stratt. And only then would you meet Rocky.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Andy Weir: Interleaving the two lets you have all the Earth's side characters and Rocky and everything, all evenly spaced throughout the book. And then, so I decided, okay, so the flashbacks need to advance the plot. So that's why I gave him... Another trope I say never to do is the amnesia plot, but I did that too because as I said, I'm a hypocrite, and I figured it's advancing the plot. So in the flashback segments, the mystery is unfolding of what the hell is Astrophage? Why the hell is he out here? And then in the present segments, the story is advancing. So as long as you keep moving the plot forward and discovering new things, the reader I think is okay with flashbacks.

Mat Kaplan: And just structurally it just works so well. I'm going to go on to another Jeffrey Toon. In Project Hail Mary, the plot moves through countless keyhole moments when tiny changes in timing, luck decisions would've doomed all of humanity. If the scenario in the book were to actually happen, do you Andy Weir really think humanity could collaborate, cooperate, develop a plan comprehensive enough to give us at least a 50/50 chance? It seems like even with the best effort, the odds aren't great. Well, they didn't have Stratt. I mean, we don't have Stratt-

Andy Weir: They didn't have Stratt.

Mat Kaplan: Maybe we do, [inaudible 00:40:06].

Andy Weir: Well, I know this sounds weird. I just have a tremendous amount of faith in humanity, and I really do think that we have the ability to solve problems collaboratively, and I would say we've demonstrated that many times in the past. Now, a lot of people have said, "Look, man, Andy, I'm not buying this concept that everyone would work together to save the world because they're not doing it right now, and we have a climate crisis in progress." I'm like, yeah, but the climate crisis is very vague.

Mat Kaplan: It's the frog in the pot.

Andy Weir: Right. Well, it's even more than that. It's like a frog in the pot, and it's unclear exactly how fast the water's heating up. All you know is that it is heating up. Whereas this is like Earth is not going to have any life on it in 30 years if we don't solve this. That's it. So that's much more clear.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, nice incentive.

Andy Weir: Pointing out cooperation, collaboration, etc. etc., I often point to COVID COVID swept through, it was a pandemic, and we had sloppy responses here and there. Some countries did other things, whatever. But globally, we as a species invented a new field of vaccination. mRNA vaccinations had never been done before. Not to humans. It was just some technology that was vaguely being considered. We went from, all right, we're no longer vaguely considering, we're going to do it right, freaking now, and boom, done. If it weren't for COVID, we would still be 20 or 30 years out from having routine mRNA vaccines. Now we just as a species went, boom, we're doing this because we got it.

Mat Kaplan: That's a wonderful comparison.

Andy Weir: And all the labs that were working on it worldwide shared their data with each other. It's unheard of in the pharmaceutical industry for multiple companies to share their data. They're trying to invent something and own it and be the only people who can do it. But with COVID, everybody's like, we don't have time for that. Make it happen.

Mat Kaplan: From Craig Griffin again, what's next for Andy? And then Orestes El Perez, will there be a sequel to this book?

Andy Weir:

So it was incredibly popular, and unlike my other books, it actually does lend itself pretty well to sequels. I don't have an immediate plan, but if I come up with something, I'll definitely write it. Basically, I need to come up with a good idea. A lot of people have emailed me ideas that are like, okay. And their ideas I've already come up with, I mean, the obvious thing is to show what happens on earth while Grace is away.

And I'm like, okay, if I wrote a Project Hail May sequel that took place entirely on earth and had no Eridians in it, there'd be an angry mob at my door, right? It's like people don't really want a sequel to Project Hail Mary. They want more Rocky. They've got a fever, and the only cure is more Rocky. That's what they want. And so other people have said, "Write the story from Rocky's point of view." And I'm like, "You want to hear the same story again?" All the plot points have had... No, that's dumb too. And so anyway, the cool thing is Rocky is a being that has a lifespan of about 750 years.

Mat Kaplan: So ignoring this particular story, what is next for Andy Weir? I mean, you told me that you have an endless supply of ideas.

Andy Weir:

I do, but I'm having a real... Okay, so first off, I took some time off because my wife and I had the baby, and so that was what I've been working on. I wasn't writing at all. Now I'm getting back into it, and I got about 20,000 words into my latest book idea, but it wasn't working. So I'm back to the drawing board right now. And people don't know how much I write and then throw away because it's just not good. I mean, it's okay. It's not good enough. Oftentimes, the best ideas I have are the ones that end up being six ideas that I've had over the past several years, glued together in such a way that they all work right.

Project Hail Mary was one of those. I had a bunch of unrelated story ideas. The idea of a guy with amnesia waking up in a ship. Unrelated to that, the idea of a woman who has unrivaled authority to do anything she wants, and she's solving a major problem. Unrelated to that, a first contact story. Unrelated to that, a mass conversion fuel story, and just all these things. I was like, Hey, I can glue them together like this, and sand off the edges painted. No one will know it wasn't a single cohesive idea.

Mat Kaplan: Could have fool me. You did fool me. I'm also thinking that it's got to feel somewhat... I mean, it must be a relief to know that you have already beaten the Joseph Heller Catch-22 syndrome. Where Joseph Heller wrote this fantastic book, one of my favorites, and then never achieved anything at that level again. You've already done it.

Andy Weir: Yeah. That's the one hit wonder phenomenon that all [inaudible 00:45:11]. But I can tell you that then the imposter syndrome remains every bit as strong. It just becomes like, I'm going to be a two hit wonder.

Mat Kaplan: But then at least I'm hoping that that just a driving force.

Andy Weir: Yeah. Well, we'll see.

Mat Kaplan: All right. Okay, so here's one from Trevor Host. Who plays Ryland in the movie and how's the movie doing?

Andy Weir:

Ryan Gosling.

Isn't that perfect?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Andy Weir: Isn't that-

Mat Kaplan: He's going to catch you to see it, folks. Isn't he going to be great in this part?

Andy Weir: Yeah. We have Ryan Gosling on board to play Ryland, which is cool because they have the same initials. Ryland Grace, Ryan Gosling.

Mat Kaplan: That's great. RG.

Andy Weir: So I think we need to get Emma Stone to play Ava Stratt.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, wouldn't it... I could see that.

Andy Weir: Actually, I could...

Mat Kaplan: She's a little young.

Andy Weir: Yeah. To me, I would to see Tilda Swinton play Stratt.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, she'd be terrific.

Andy Weir: Yeah, she'd be fantastic.

Mat Kaplan: What's the status of the project?

Andy Weir: We have the directing duo of Phil Lord and Chris Miller set to direct. Drew Goddard has already written the screenplay. Drew Goddard made the adaptation of The Martian, so we know he's good at what he does. The screenplay is great. Judi Dench could be Stratt, says William Faulkner. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Let me stop you for a moment, because there are going to be people out there who don't realize that this is not the William Faulkner who is a ghost who speaks to you in your head. This is actually one of our viewers today, one of our participants. He also says, "First I enjoyed the book and from this conversation, you, Andy, clearly enjoy the investigative aspect. I wonder, what are the social science aspects that you would like to have investigated more and, or further integrated into the story, the social science aspects?"

Andy Weir: I guess I don't understand the question.

Mat Kaplan: We're talking about the relationship between Rocky and Ryland or what happens-

Andy Weir: It's a bromance, for sure.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, and I'm also thinking what happens on Earth too.

Andy Weir: Well, sure, yeah. Oh, that sort of stuff. Yeah. I don't really like doing that stuff because it's very difficult to tell a story about tumultuous social upheaval. It's like you can create some characters who experience it, and you can show things from their point of view. Stories that show that upheaval in a fictional setting always fall flat for me. If it's a story about the Holocaust or something like that happened, then it has, okay, all of this happened and it makes me take everything very seriously. But if it's a fictional catastrophe or it's a fictional social upheaval that is horrible, that sort of thing, I have a really difficult time buying into it.

Mat Kaplan: Here's one from Jeff Ouyang. At relativistic speed, any impact with space dust could cause a catastrophic hull breach. Was this considered during the writing? This occurred to me. You didn't mention that there's a big deflector on the front of the Hail Mary like they have on the enterprise.

Andy Weir:

That's true. There is not, and there doesn't really need to be one because there isn't space dust. Okay. So basically the Hail Mary, when it's leaving our solar system, when it passes through the Oort Cloud past the orbit of Neptune, it's not going anywhere near the speed of light yet, right? It's still accelerating. It doesn't get up to the truly relativistic speeds until it's deep into interstellar space, and also it is slowing down on the other half of it. So by the time it gets into the Tau Ceti system, it's going much slower. So it's only in the interstellar space way outside of the heliopause of both our solar system and Tau Ceti that it's going these relativistic speeds. And in that part of space in that there isn't dust, there are just atoms. There's maybe one hydrogen atom per cubic meter. It's like a vacuum better than we can create in a lab on earth. Okay.

However, it is still a major issue because although it wouldn't cause a catastrophic explosion or anything like that, these particles from the ship's point of view are hydrogen atoms or helium atoms going almost to speed of light. And that is radiation. That's radiation. And so you'll get like radiation sickness, you'll be bombarded with radiation. Yeah. There's only one per cubic meter. But do you know how many cubic meters you're passing through when you're going almost the speed of light?

Mat Kaplan: A lot.

Andy Weir: A lot of them. In fact, it's about C times the cross-section of your ship, right? Per second. And so you're getting bombarded with massive amounts of radiation. However, they did account for that because Astrophage is a super cross-sectional quantum thing. Nothing can quantum tunnel through an Astrophage cell membrane. That's how it manages to keep the neutrinos inside. Under normal circumstances, a neutrino can-

Mat Kaplan: [inaudible 00:50:12] away. They boil off. Yeah.

Andy Weir: They would just leave. In fact, a neutrino can pass clean through the planet Earth without hitting a single atom. But Astrophage cell membranes have this super cross-sectionality. That means absolutely nothing can quantum tunnel through it. So as a result of that, they put a very thin layer of Astrophage all around the hull, and then these extremely fast moving atoms cannot quantum tunnel through it. They must collide with the Astrophage. It's a lot of energy. They'll kill it, but it's like, okay, you lost one Astrophage cell here.

Mat Kaplan: This takes me back to one of my questions that-

Andy Weir: And by the way, that's why Rocky's crew died.

Mat Kaplan: I was going to say, what a great bit because you had to figure out why does the rest of Rocky's crew die? And it's because he was surrounded by Astrophage most of the time.

Andy Weir: He was the engineer for the ship, and so he spent all his time down by the engines and by the engines is where they kept all the fuel. So that's why Rocky lived and the rest of his crew died.

Mat Kaplan: While we're on the topic of Astrophage, this is... Like I was starting to say, this is one of the prompts that I threw out to people. One of my favorite things about the story has always been how Astrophage is both the threat to human survival and appears to offer the only pathway to our salvation.

Andy Weir: I felt good about that.

Mat Kaplan: And the stars. And the stars. Devon O'Rourke added, I love this aspect of the story. Physics is just physics. It doesn't have an agenda. It doesn't care about you. It just is, at least it's predictable and our understanding is accurate. Yeah, really, that's one of my favorite elements of the book.

Andy Weir: Thanks. I really felt good about that when that clicked together. That was a shower moment or whatever. I'm like, oh.

Mat Kaplan: Nathaniel Fisher. What plot point was the most difficult or challenging to develop?

Andy Weir: Well, there were some scientific issues. I had a really tough time coming up with how Earth could possibly make enough Astrophage to do that mission. Because I worked it out. If we took the entire global power grid, every single watt of electricity in every country, and turned it all of that energy with 100% efficiency into Astrophage, it would take us centuries to make enough for just the Hail Mary's fuel tanks. So I'm like, got to come up with something else. And so that's when I came up with the black panel's idea. But I went through a lot of ideas that didn't work first. I was like, well, Astrophage reproduces via heat. Could they use a volcano or a lava pit or something like that? Could they do geo, could they deliberately dig holes or just nuke a hole or whatever to get a ready supply of geothermal heat? And even then, it turned out to be you'd have to create an artificial volcanic eruption larger than anything that's happened in the Anthropocene era.

Mat Kaplan: Not fixed for the planet.

Andy Weir: Well, yeah. Yeah. And so I was like, no, lava won't work, but the black panels did.

Mat Kaplan: This is another thing that I loved about the book. There's that character who really, it's his thinking, his work that leads to this solution. But he's horrified by it. I mean, he breaks down, right?

Andy Weir: Oh, you're thinking of the clerk. Yeah. So the guy who invented the black panels was a New Zealand gambling addict.

Mat Kaplan: He's the questionable-

Andy Weir: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: The character, right. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Andy Weir: But no, yeah, the clerk who is the French climatologist, he's one of the only climatologists in the world who consistently makes reasonably accurate predictions of what the climate is going to do based on the emissions of government and stuff like that. And they end up hiring him to say, okay, how can we stabilize? How can we keep alive during long enough when this happened-

Mat Kaplan: ... to figure it out.

Andy Weir: And he concludes, okay, we need greenhouse gases galore. And a really good way to do that is to melt a lot of Antarctica all at once so that it releases all the methane. Methane's actually a great solution because methane causes is a massive greenhouse gas, but it breaks down after about 10 years. So they're like, release this methane like crazy. It'll give us a short-term heat retention on the planet, and then it'll be going away by the time the actual solution comes. And then he just breaks down, Craig. Here we've got this European eco nut tree hugger, climatologist guy who ultimately is responsible for nuking Antarctica. He says, "Well, we could nuke the Ross Ice Shelf and make it break off into the ocean. Then it'll melt." So the United States government does it.

Mat Kaplan: The United States government through Andy Weir nukes Antarctica.

Andy Weir: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: Here's one that I was going to ask you if somebody else didn't, it's from Nathaniel Fisher, how did you come up with Xenonite as a key material? And I think my God, humanity is going to be left with Astrophage and xenonite.

Andy Weir: It's going to be in good shape if they survived. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Andy Weir: Xenonite was a hand wavy thing I had to come up with, because I wanted Ryland and Rocky to be able to interact fairly easily. So I wanted them to just have some clear material between them like glass. But Rocky's atmosphere is 29 times that of Earth's atmosphere. If you actually wanted to make something like that, you'd need a meter or more of glass. It'd be ridiculous. I decided that, well, we've seen this in earth history, in the history of our own planet and civilizations on our planet. It's not like technology is a single line that you work on and you're ahead or behind some other civilization. There's a lot of different directions that technology can go. And one of my favorite examples of this is how in Europe, they were big into wine in the ancient days, Romans. And then moving forward into the so-called dark ages, which is not a fair name for it. Lots of wonderful things were invented during the dark ages. It was not a time of scientific halted progress. But anyway-

Mat Kaplan: Especially not in Western Europe. Yeah.

Andy Weir:

Not in Western Europe, they invented the yolk, which is like you put that over your ox and it could plow your field much better. Seems obvious to us now. Nobody came up with it before that. It changed agriculture anyway. I don't like it when people call it, oh, the dark ages. Nobody invented anything. No, they just didn't write it down on paper. Or rather, they did write it down on paper for the first time and all that paper rotted. So you don't know what happened anyway. So during that time, Europeans were really into wine. In making wine, you need to be able to look at it. When it's in a bottle, you need to be able to see it, to see if anything is going wrong. So they needed to invent clear glass. They needed to invent a material that could hold a liquid indefinitely, but that you could see through.

And so that's when they figured out, Hey, if we melt sand, we get that. Okay, cool. And that got the Europeans working in that direction. Meanwhile, in Asia, the Chinese of that same era were like, we don't need to look through stuff. So they didn't care about seeing what was inside of liquid containers. They figured we could just look at the liquid, right? And so they got incredibly good at pottery. That's why you have these Asian ceramics and porcelain and stuff like that. They could do stuff that's paper thin, just they're incredibly good at it. And Europeans got really good at glass. But then over time, Europeans figured out that with glass, you can make optics and so you can make glasses, spectacles. And that had a tremendous effect on European history because it meant the smartest people in your society could be effective reading and writing for a longer portion of their life because you could correct their vision.

And the Asians did not have that. And that is part of the reason Europe had much faster growing technology from that point forward was simply because they needed to be able to look at their wine. Okay. But in this, I would point out... Okay, so that's all interesting, but I just want to point out that if you just teleported two people from those two regions together and gave them a common language and they could talk, the Chinese guy would be incredibly impressed on what Europeans can do with molten sand, right? And the European guy would be incredibly impressed on this level of skill that the Chinese guy has with ceramics and porcelain, right? So different societies will advance different technologies at different rates. And so I decided that Eridians advanced materials technology well beyond us. And I'd also already decided that just for another fun thing to turn tropes on their head, is that we are the advanced alien race. We're the advanced alien species.

Mat Kaplan: We are the ones from computers in relativity.

Andy Weir: Computers, we understand relativity, we know a lot more about the physical universe and how things work. And it's not because we have eyes and they don't. It's just for one reason or another, our technology ended up being much more advanced, however they kick our asses when it comes to materials technology. So that's what Xenonite is. What is it? Why is there xenon inside? I never explained.

Mat Kaplan: I just got a text message from Scotty of Star Trek. He'd like to trade some transparent aluminum for a sample of xenonite.

Andy Weir: That sounds fair.

Mat Kaplan: We're just about out of time. I got just one more for you. And it comes from Rich black. Do you still get potatoes in the mail?

Andy Weir: No, I haven't gotten potatoes in the mail in a long time. That was a weird little time. I don't know why that became a thing.

Mat Kaplan: I hope people know what we're talking about. If you read The Martian, you know potatoes, right? Okay.

Andy Weir: Potatoes are a big deal. Yeah. The Martian-

Mat Kaplan: Did he run out of salt or ketchup? I forget.

Andy Weir: He ran out of ketchup at one point. Yeah. But yeah, for some reason it became a thing for people to mail me potatoes. And I mean, I get it. I see the connection, but it would just end up with me at my package receiver throwing potatoes away. Because I don't eat stuff that people mail me, right?

Mat Kaplan: No, no, thank you.

Andy Weir: And also, it wouldn't be in a package. It would literally be a potato with postage taped to it. And I got a lot of these.

Mat Kaplan: Kudos to the US Postal Service.

Andy Weir: They will deliver just a potato with postage on it. If you're curious. They will.

Mat Kaplan: Do you remember the time you and I were on a stage and I had my Martian survival kit? And I said it had the three most essential things that you need to survive by yourself on Mars. And we opened the bag and inside was a roll of duct tape, a potato, And then you said, "The bag's empty." And I said, "No, it's not. It was full of air."

Andy Weir: It was full of air.

Mat Kaplan: Andy, it is always, always so fun.

Andy Weir: I was thinking the other day, I don't think anyone has interviewed me as many times as you have.

Mat Kaplan: Just lucky. I guess.

Andy Weir: I'm lucky.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. I just have the best time. I hope everyone else out there, I bet they have enjoyed this almost as much or maybe even more than I have. It's hard to imagine because it is just delightful and I cannot wait to talk to you again when the movie eventually reaches us or-

Andy Weir: I mean, they haven't even cast anyone but Ryland yet. So it's early days for sure.

Mat Kaplan: But any other reason, whether it's here in the member community or elsewhere, I look forward to any opportunity to talk once again, it is just wonderful.

Andy Weir: It's always great talking to you, Mat. Thanks for having me.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. Thanks for joining us here in the Member Community Book Club.

Andy Weir: All right, bye. Thank you for your questions, and thanks always, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: So ended my live 2023 conversation with author Andy Weir about his spectacular book Project Hail Mary. The movie version is set to premiere in 2026. We'll be back on the third Friday of August with another of our wonderful author conversations drawn from The Planetary Society Member Book Club. Want to join the club? Then become a member of The Planetary Society. You'll be part of all of our great work. Find out more at planetary.org/join. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our members. You can join us at planetary.org slash/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Casey Dreier is the host of our monthly space policy edition. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. I'm Mat Kaplan, your host of the Planetary Radio Book Club edition. And until next time, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth