Planetary Radio • May 05, 2021

Author Andy Weir and Project Hail Mary

On This Episode

Andy Weir

Author of The Martian and Project Hail Mary

Rae Paoletta

Director of Content & Engagement for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

It is always such fun to welcome back Andy Weir. The author of The Martian and Artemis has just published his most entertaining and inventive novel yet. Project Hail Mary gives an unlikely protagonist the job of saving humanity. Andy also shares his thoughts about the Mars helicopter Ingenuity, his hopes for NASA, and his low opinion of “the goldilocks zone” for life. Someone will win the book in Bruce Betts’ space trivia contest. We also introduce new Planetary Society editor Rae Paoletta. She has written about the mysteries of lightning on Jupiter.

Related Links

- Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir

- Andy Weir

- Why Lightning on Jupiter is a Planetary Unsolved Mystery

- Table Mountain in South Africa

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prize:

A copy of Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir.

This week's question:

On Michael Collins’ second EVA, what did he collect from the Agena target vehicle AND what unrelated item did he lose during that EVA?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, May 12th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

Who was the asteroid Kaplan named after?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the April 21, 2021 space trivia contest:

What is the only official IAU constellation with a name that is derived from a geographical feature on Earth?

Answer:

Mensa is the only official IAU constellation with a name that is derived from a real world geographical feature on Earth: Table Mountain in South Africa.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Author Andy Weir returns this week on the 1,000th episode of Planetary Radio. Welcome, I'm Mat Kaplan of the Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. No kidding, 1,000 episodes of Planetary Radio and the Space Policy Edition, and there are a few of you who've been us from the beginning. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. No one is more fun to talk to than Andy, and now he has written what I believe is the best, the most invention, and the most fun of all his novels.

Mat Kaplan: He'll be in here minutes to tell us about Project Hail Mary. We'll also squeeze in a few thoughts about what's going on in the real world of space exploration. Want a copy of the book? You might win it in Bruce's new space trivia contest. I've also got a new Planetary Society colleague to introduce. Rae Paoletta has just published her first article at Planetary.org and it's a great start. Here's something that I rarely do upfront, but maybe our anniversary has emboldened me.

Mat Kaplan: You know all those other podcasts that beg you to subscribe, rate, and review in Apple Podcasts? Count us in. If you love our show, even if you just like us, really like us, please, share the love or the like. There are a lot more space enthusiasts out there who don't know we exist. And don't they deserve to know? Okay, onto a few headlines from the current edition of The Downlink, the Planetary Society's weekly newsletter. It starts with a tribute to the great Michael Collins, Apollo 11 command module pilot.

Mat Kaplan: He passed away last week at 90. Check out his beautiful photo of Lunar Module Eagle suspended over the moon, with our pale blue dot in the background. More about Michael later when Bruce arrives. Did you doubt that Ingenuity would point a camera back at the mothership? It happened on the Mars helicopter's third flight. The shot of Perseverance is kind of grainy and fuzzy, but hey, it was taken by a flying machine on Mars. We also got word that the experimental device known of MOXIE has successful turned some of the red planet's abundant carbon dioxide into oxygen.

Mat Kaplan: And that maybe as historic as the successes of Ingenuity. Work by SpaceX on the recently awarded NASA contract for a human lunar lander has stopped as consideration is given to the protest filed by both Blue Origin and Dynetics. In the meantime, the core stage of the Space Launch System has finally made it to the Kennedy Space Center. There's a lot of doubt about whether it will fly the Artemis 1 mission by the end of this year. More is waiting for you at Planetary.org/downlink. Rae Paoletta is a new editor at Planetary Society.

Mat Kaplan: She has arrived with a terrific resume, including science writing stints at MTV News, Gizmodo, and Inverse, where she co-hosted the I Need My Space Podcast. Bill Nye was Rae's childhood hero. Now, she works for him and our members. She was at her New York City home when we talked for the first time. Rae, welcome to Planetary Radio and much more importantly, welcome to the Planetary Society. We are thrilled to have you, and I think as people begin to see your work, they will also be very happy. Welcome.

Rae Paoletta: Mat, it's a pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

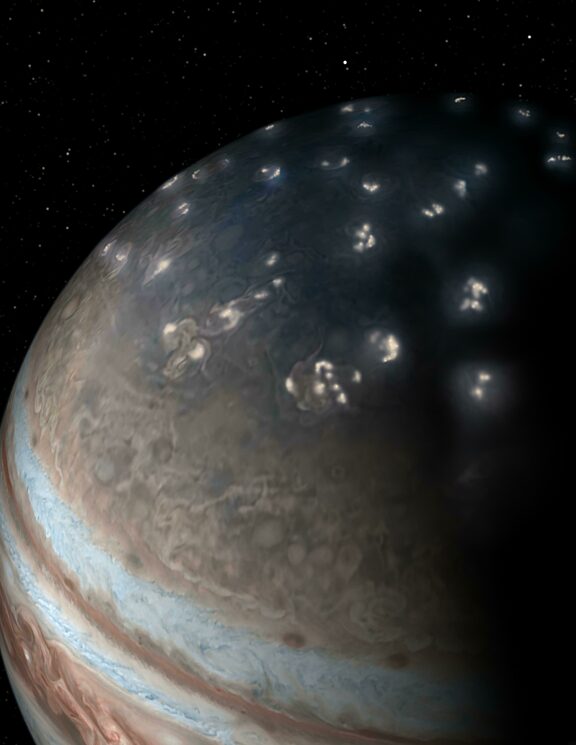

Mat Kaplan: When we talked about your work, it is now visible as of yesterday as this show becomes available. It's a May 4 article called Why Lightning on Jupiter is a Planetary Unsolved Mystery. That was a tease. We're going to get to that, but first, I said a little bit about what you were up to before you got to us. But what brought you to us? What drove you to join our happy band of the Planetary Society?

Rae Paoletta: I've been a long time fan of the Planetary Society's work, so it's just so cool to be a part of it now.

Mat Kaplan: Good enough for me. Let's talk about Jupiter. I agree with you, you talk right at the top of your article about Jupiter's beauty, though I have given up on my dream of viewing those swirling clouds up close and in person. It's not just the radiation. It's I don't think I'm going to get a ride. The other thing you said at the top of your piece though, you asserted that its weather lacks subtly in the best way. What do you mean?

Rae Paoletta: Well, I think for all of us space enthusiasts, we like a little bit of chaos, right? We like to have something that we can see and say, "Wow! That really boggles my mind." And Jupiter is... I mean, that's what it's great at, right? Surprises. When we see things like its polar cyclones or something like the Great Red Spot, I mean, the storms on Jupiter are I would say world-class, but it's really in a class of its own on a very different world.

Mat Kaplan: Indeed. Lightning, are we now confident that it really does have lightning more or less as we know it on earth? Maybe less like we know it on earth.

Rae Paoletta: That's a really good question. I think that it kind of remains to be seen what the details are regarding the lightning on Jupiter. The cool thing is that now we know not only is there almost certainly lightning on Jupiter, there are different kinds maybe. Only in the last few years have scientists particularly on the Juno Mission, they've began to study what they think is something called a shallow lightning, which functions very, very differently from how lightning is on earth.

Mat Kaplan: Are we beginning to understand or at least come up with hypothesis about how this lightning takes place? I'm leading up to this great term that you mentioned and new to me in the article, mushballs.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. It's kind of hysterical. They're almost like slushies of Windex in a way. The mushball theory seems to be very tied in some way to the formation of shallow lightning. It's basically that these ice crystals are flung into Jupiter's high atmosphere. And at that high altitude, it's far too cold for water. Scientists had already hypothesized it's somewhere along this level of the atmosphere there was some kind of ammonia hale mixture that the mushballs essentially become.

Rae Paoletta: It's really interesting because here on earth we think of lightning as something that's only tied water clouds. But as we see on Jupiter, there's always a possibility for something to be a curve ball or a mushball.

Mat Kaplan: Yes. Yes. Is there a decent shot at learning more as the Juno Mission continues?

Rae Paoletta: Yes. In a lot of ways... Juno's primary mission wraps up this summer, but its extended mission begins in August 2021. I think we're just gearing up to see the coolest parts of the mission. I think that we're going to learn as the spacecraft gets closer and closer to Jupiter and its orbit even more hopefully about the mushball hypothesis and how it could be related to something like shallow lightning. I'll be waiting. I'm excited.

Mat Kaplan: Me too. A lot to look forward to. I look forward to many more conversations with you, Rae, here and elsewhere around the society. Congratulations again on joining the staff.

Rae Paoletta: Many, many thanks. Thank you so much.

Mat Kaplan: That's Rae Paoletta. She is an editor now for the Planetary Society. You can read her first piece, it's at Planetary.org, Why Lightning on Jupiter is a Planetary Unsolved Mystery. I love talking with Andy Weir, and I love his new book. If you enjoyed The Martian and his more Artemis, I suspect you will also enjoy the ride provided by Project Hail Mary. I really do think it's his best yet. I don't think there's anything else I need to say, except fasten your seatbelts. Andy Weir, welcome back to Planetary Radio. It is always such a pleasure.

Andy Weir: Great to be here. I kind of feel like this is my home away from home.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad. Drop in anytime. I mean it. As you know, I first read Project Hail Mary months ago in preparation for the conversation that you and I had during the Planetary Society's Planetfest celebration back in February. I picked it up last week so that I could refresh my good memories. And damn you! If I wasn't completely captured again, this... I'm serious. This maybe the cleverest... Is that a word? The most clever science fiction novel I have ever read, also the most fun, and the best laughs I've had from a book in ages.

Mat Kaplan: And yet, it's about the all out effort to save earth from the greatest threat it has ever faced.

Andy Weir: Well, thank you. I'm glad it had such a good effect on you. That's the goal.

Mat Kaplan: I'm thanking you. You shouldn't be thanking me. I was so reluctant to say much about the story because I didn't want to ruin the wonderful surprises that are ahead for readers, and there'll be lots of them. Then I looked at the glowing reviews as I just told you in Amazon and elsewhere, I'm a little less worried now, but I want to warn listeners, there may just be some spoilers in the coming minute. Why don't you start by saying what are you comfortable saying about the story that is Project Hail Mary?

Andy Weir: Well, in a pre-spoilery way, the story starts with a man waking up with complete amnesia. Literally anything in the book that I tell you about is kind of a spoiler. But you very quickly find out, through some experimentation, he realizes he's aboard a spaceship. And as his memory start coming back to him, he realizes that he's on a last ditch effort mission to save humanity from an extinction level event. No pressure.

Mat Kaplan: It's a Hail Mary pass.

Andy Weir: It is a Hail Mary. Yup.

Mat Kaplan: There s something else that I want to thank you for. You have given 15 seconds of science fiction fame to one of the most maligned and underappreciated performers in the history of show business. I'm talking, of course, about the great Shemp Howard.

Andy Weir: Shemp Howard. That's right. He's a good stooge.

Mat Kaplan: He's a good stooge. I hated him as a kid, but he grew on me later. I could see...

Andy Weir: Well, as a kid, you're like, where's Curly?

Mat Kaplan: Exactly. Exactly.

Andy Weir: Give me some Curly. I don't want Shemp. I mean, every kid, Curly's your favorite stooge, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, of course.

Andy Weir: I mean, nobody's like, "Ooh, Larry is my favorite." No, Curly.

Mat Kaplan: Poor Larry. Poor Larry. I have to say, Shemp is there for a good reason because he represents the first maybe sign of hope for humanity.

Andy Weir: Yeah, within the story... I mean, basically the premise of the story is that an alien, a genuinely extraterrestrial microbe, enters our solar system. These microbes are... They're not intelligent. They're just like the size of bacteria, whatever. They grow on the surface of stars in the same way that algae grows in the ocean. They collect energy. They migrate to nearby planets to breathe. Because the star itself will only have hydrogen, so it needs other atoms, other elements to be able to reproduce.

Andy Weir: Then it comes to the star and the life cycle begins anew. When it's on a star, it's also sporing out. It's making god knows how many of these, like 10 to the 20th of them, whatever, and it's sporing out in all directions to seed other stars. It's just like mold or algae or anything else. Problem is, it's breathing so out of control on the sun that the solar illuminants is going down. Shemp is the nickname given to our protagonist at one point has three of these... Oh, by the way, they're called astrophage.

Andy Weir: It's what the scientists of earth call it. It's Greek for eater of stars, which is a bit dramatic. It's not eating the sun anymore than algae is eating the ocean, but it lives there and it's causing us a problem.

Mat Kaplan: Eating a lot of photons. That's what it does.

Andy Weir: It's eating a lot of photons. Our hero was given... There was a space mission to collect a sample of the stuff and everything, and our hero is able to get a hold of three cells, three astrophage cells, just three, to experiment with. He calls them Larry, Moe, and Curly, and then basically figures out how to make them breed. He figures out the process to artificially make astrophage reproduce. At one point, he has a fourth one and he calls it Shemp. That's how we get Shemp.

Mat Kaplan: And I defy any other interviewer to come up with that question for you.

Andy Weir: That is new. That is new. I have not heard that one.

Mat Kaplan: There's a brief tribute to the immortal Bullwinkle J. Moose too, but we don't have time to go into that. I told you in February that I think there's an average of one ingenious concept and one good laugh in every page of Project Hail Mary. I tested this by turning to random pages and it holds up. I stand in awe.

Andy Weir: Oh wow. Well, thank you so much. I mean, but I imagine the copyright information page wasn't that hilarious to you.

Mat Kaplan: It was a random sample. I guess I didn't hit that. Your hero, and I think he earns the title over the course of the book, he's a middle school science teacher, continuing the spoilers here, named Ryland Grace. I think he's as brilliant and funny as Mark Watney, The Martian, but maybe not quite astronaut material at least when things got started.

Andy Weir: No, not at all. You learn through reading the book that he wasn't really the first choice for this mission. There's a somewhat small pool of potential candidates due to the rigors of the mission.

Mat Kaplan: Say no more.

Andy Weir: It's a long story and that story can be found inside the pages of Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir. Available now. He wasn't really anybody's first choice, and he certainly wasn't his own first choice for this mission either.

Mat Kaplan: That's putting it mildly. There are two other really important characters in the book, one of them, only one of them is human though. She really maybe somewhat superhuman come to think of it. Tell us about Eva Stratt.

Andy Weir: Eva Stratt. Once earth and the people of earth find out about astrophage and realize that the sun's dimming, they start looking around trying to find out what's going on. And then once they get a sample of astrophage and everything like that, they also started looking at other stars in our neighborhood, nearby stars, and all those stars are dimming too. All the stars in our area are affected by astrophage, except one. For whatever reason, they don't know why, the star Tau Ceti, which is 12 light years away, is not affected astrophage at all.

Andy Weir: It's not dimming in any way, even though it's well inside of the area where all the other stars are affected. It turns out, astrophage itself has the ability to propel itself through space, and it has this incredible ability to store enormous amounts of energy as mass internally and then release it as light. They developed a space propulsion system that uses astrophage and their plan is to make a genuinely interstellar ship using astrophage to propel it to send scientists to Tau Ceti to try to figure out what's going on.

Andy Weir: Now, this is the largest, most expensive space mission or even project of any kind in human history. They put one person in charge of it, and her name is Eva Stratt. She's Dutch. She's from The Netherlands, and she was an administrator at the European Space Agency. She's definitely the right person for the job. Due to her responsibilities and the urgency of getting this done, she is given an amount of authority that probably no human being has ever had. She can literally just tell countries what to do and they'll do it.

Andy Weir: She has a no nonsense attitude, because what she's doing here, the survival of the human race depends on it. She's absolutely not interested in anything else. She doesn't have time for comfortable morality or anything like that. She's stern.

Mat Kaplan: She's ruthless.

Andy Weir: She's ruthless in her pursuit of this, but never selfish and never mean spirited or anything like that. She's just getting this mission, getting it out there, getting it done is the only thing that matters. Literally everything else is less important. She would happily throw a hundred kittens into an incinerator if it would add 1% more probability of this mission succeeding and she'd sleep well that night.

Mat Kaplan: No kittens were harmed in the making of this radio interview.

Andy Weir: There are no kittens in any incinerators in this book.

Mat Kaplan: You've given away a lot. And I want to assure everybody, he could give away every big reveal in the book and it would still be maybe the best science fiction book you've read in a long time. Don't worry.

Andy Weir: There was a spoiler warning. If you're here...

Mat Kaplan: There was.

Andy Weir: If you're listening to this and you haven't read the book yet, I mean, if you haven't mind to read the book, I would urge you to read the book first, especially because we haven't even gotten to the biggest spoilers yet.

Mat Kaplan: No. And come on, you made a choice, folks. You heard us warn you. I love the irony that this microbe, which has the potential and is on its way to knocking off all of humanity, is also in a sense our salvation because it gives us the ability to travel between the stars.

Andy Weir: Yeah, it is the cause of and solution to our crisis. I really like that one. I came up with it. I mean, I had a lot of pieces of the story in the mind. But when they started to come together, I'm like, "Oh yeah. This is really cool," because this MacGuffin provides the problem and also enables the solution, but doesn't make the solution too easy.

Mat Kaplan: I want to talk to you about life, the universe, and everything.

Andy Weir: Life.

Mat Kaplan: You actually do create some. Ryland Grace, that's our hero, he says a couple of times I think that the Goldilocks Zone is bullpucky.

Andy Weir: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: Those are fighting words to a lot of people who come on this radio show.

Andy Weir: Yeah, especially Planetary Society people.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know. We put in air quotes "life as we don't know it," which your microbes definitely qualify. What does he mean when he says the Goldilocks Zone is bullpucky and do you agree with him?

Andy Weir: Well, within the book, Ryland Grace before he was a junior high science teacher was a speculative exobiologist. He's got a PhD. He's very skilled at molecular biology and his career was writing papers on how alien life could develop, what might some other forms of life that could exist in the universe that are just physically possible to exist. One thing he said in a paper that he wrote... Remember this is all fiction. In a paper he wrote, he said that the Goldilocks Zone is BS, because he also said that the assumption that life requires liquid water is also BS.

Andy Weir: Just because all of the chemical reactions that are in life on earth and all the chemical reactions that we've even come up with that could support life, all of those require liquid water. But he says in his paper that doesn't mean that the only life anywhere in this vast universe of ours will be on planets that have liquid water. Some other set of chemical reactions... I mean, all you need for life is a bunch of molecules that undergo a bunch of chemical reactions that make a copy of those molecules.

Andy Weir: That's all you need for life. You don't need liquid water for that. He wrote this paper and it ultimately led to him being kind of ostracizes in the exobiology community, which is what led him to leave it entirely. It was too stressful a job for him, and he became a junior high science teacher, which he loved, and he found his calling is teaching. As for me, I do also believe that the so-called the Goldilocks Zone is BS because the idea of the Goldilocks Zone is like, hey, here's the area...

Andy Weir: For those few listeners who are fans of the Planetary Radio program but don't know what the Goldilocks Zone is, the idea is it's a region around a star, each star would have its own different definition of a Goldilocks Zone, where life is likely to survive. It's called Goldilocks because it's not too hot, not too cold, right? It's just right. In this band, this kind of a ring around a star, is where the temperature of any planet in that band would be suitable or conducive to having liquid water.

Andy Weir: Anywhere too close and the energy from the star will be boiling off the water. Any too further away, you'll just have a bunch of ice. But I would say the one simple thing is that's kind of ridiculous because the boiling point of water is dependent on the atmospheric pressure. If it's really hot and you have a really high pressure, you can have liquid water.

Mat Kaplan: Sure.

Andy Weir: In fact, that kind of comes up, although Ryland went a step further and said water is not required at all. Since we're well into spoiler territory, he's shown to be wrong.

Mat Kaplan: Well, that's right because they do need some of the basic...

Andy Weir: They need liquid water.

Mat Kaplan: Some of the same basic building blocks of life.

Andy Weir: Pretty much all of the same things, because, spoiler, spoiler, spoiler, we learn that all of the life in the book is related. There was a panspermia event four billion years ago that life actually evolved in the Tau Ceti star system and a progenitor of astrophage. Some ancestor of astrophage four billion years ago was also spreading out and seeding itself to stars. And that's what ended up seeding life onto a few planets in the area, including ours and another one. Astrophage, when they take it apart and look at it, inside they find boring machinery of cells.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, mitochondria, stuff like that.

Andy Weir: Mitochondria, ribosomes, DNA, RNA. It is very, very similar to earth life, and they also find that astrophage is full of liquid water. How the hell does something that lives on the sun have liquid water? Well, because astrophage takes heat energy and turns it into mass that it stores, so all the heat going into astrophage is... Not all, but a lot of the heat going into astrophage is turned into just stored energy and the temperature inside of the astrophage cell itself is much, much lower than the temperature outside.

Mat Kaplan: Brilliant stuff.

Andy Weir: Thanks.

Mat Kaplan: It really is. Of course, that particular mechanism that drives the astrophage it's in the realm of Arthur C. Clarke's definition of magic, because who knows?

Andy Weir: Right. I mean, in any given science fiction story, no matter how rigorous the author wants to stick with real science, if you dig deep enough, you're going to find the BS, right? In my case, you have to dig all the way down to the quantum level to find it, but it's there. The means by which astrophage stores energy, I defined it because I go way down the rabbit hole. I really enjoy the research. I do way more than I should or need to.

Mat Kaplan: Always.

Andy Weir: I waste a lot of time that way. The means that astrophage uses to store energy is it turns heat energy into neutrinos. How? Shut up, that's how. And then it stores the neutrinos until needed. How? Again, shut up, that's how.

Mat Kaplan: What's that line from the guys who did the Star Trek technical manual? How does the Heisenberg compensator work? Very well, thank you.

Andy Weir: Very well. Yes. Well, I invented some new physics. I said that astrophage... The production neutrinos, which I call neutrinogenesis, happens kind of in an area between the astrophage's cell wall and the rest of the cell. There's an area where there's free hydrogen ions, just protons, banging around. Somehow within this area, those proton-proton collisions, the kinetic energy of those collisions gets turned into neutrinos. Two neutrinos going opposite directions to balance energy and momentum.

Andy Weir: And then I said that that process of neutrinogenesis also causes the cell wall to have a property, that I made up, called super cross-sectionality. You think of a super conductor, that's an electric conductor that has literally zero resistance. Not very, very little resistance, but actually zero. Well, super cross-sectionality is the cell membrane of astrophage cannot be quantum tunneled through. No particle can quantum tunnel through it. It cannot be on one side and then be on the other side. It must collide.

Mat Kaplan: That's wonderful.

Andy Weir: That is how it's able to contain neutrinos, which are notoriously difficult to control.

Mat Kaplan: Yes.

Andy Weir: And then neutrinos themselves are Majorana particles, which means they're their own anti-particle. If you do manage to smash two neutrinos together, they will annihilate and turn into photons. And they'll turn into photons in the infrared band, because that's the amount of energy that they have. If two neutrinos collide, they turn into two photons, and those two photons will have the mass energy that the neutrinos had, which allowed me to calculate the frequency of light that astrophage expel as thrust.

Mat Kaplan: Which is actually a key point in the book.

Andy Weir: It's important, yeah. It ends up being called the Petrova frequency in the book.

Mat Kaplan: You keep doing all that research because it what makes all this stuff so much fun. Could we say that behind all of this is... In the immortal words of Jeff Goldblum, life finds a way.

Andy Weir: Life, uh, uh, finds a way. Well, sure. I mean, this is the most speculative novel I've written, right? The Martian you can say like, "Yeah, I could see that happening." Artemis, you're like, "Sure. Something like that can happen. We'll probably have a city on the moon someday," and whatever. But this is like, "Okay, an extraterrestrial microbe comes into our system." Well, it's much more speculative. But I wanted to stick with just like see what I can do about not violating physics as much as possible.

Mat Kaplan: And so much of the rest of this is completely based in actual science that we know about and can conduct now and it comes up pretty much every page. It's part of the fun. Andy Weir will tell us more about Project Hail Mary when we return. He'll also share some expert opinions about Ingenuity, the Artemis Lunar Program, and more in barely a minute. Stick around.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is once again brought to you by Aura Frames. Mine is still humming away next to me as I write this. Okay, not literally humming because it's silent. It's showing me beautiful images of my family, our trip to the mountains a few days ago, and anything else I or others I invite in want to give me. Aura is everything those old digital frames wanted to be, which is why it is recommended by over 130 gift guides, including Oprah's Favorite Things.

Mat Kaplan: Brilliantly easy set up and uploads to unlimited storage from the Aura app, great image curation tools, and it's energy conscious. You can even react with emojis. Did I mention the display is gorgeous? Aura has restocked for Mother's Day, but you should probably hurry. If you do, you can save up to $100 off your purchase of an Aura Digital Frame if you use the code "planet." Visit AuraFrames.com to redeem this special offer. It's good through Mother's Day. That's AuraFrames.com with the code "planet."

Mat Kaplan: I took notes about the remaining major character in the book. I'm so reluctant to say anything about that character because...

Andy Weir: A second double spoiler ring.

Mat Kaplan: Really. Turn off your radio or your device for the next five minutes.

Andy Weir: Now you're not just in the spoiler compound. You're about to enter the spoiler inner sanctum.

Mat Kaplan: I love that. I'm not going to totally give it away, but...

Andy Weir: We can if we want to.

Mat Kaplan: We have too many smart listeners. No, here's how it goes. First of all, are you a fan of the great Randall Munroe? XKCD.

Andy Weir: Of course.

Mat Kaplan: Of course, you are. Of course.

Andy Weir: Everyone is.

Mat Kaplan: Everyone should be. You probably know his book. I mean, I got it right here. You can see it.

Andy Weir: The Thing Explainer.

Mat Kaplan: Where he takes on much of the universe and a lot of technology and manages to explain it all in the thousand most commonly used English words. You made me think of that book because of the way Dr. Grace has to communicate periodically.

Andy Weir: Oh yes. In Thing Explainer, I especially like the Up Goer Five.

Mat Kaplan: Saturn V for those of you who haven't read the book. There's much more like that. Listen, we're really recommending two books today. I'll tell you a secret. My dream Planetary Radio segment to get you, Randall Munroe, and JPL chief engineer Rob Manning together for a conversation about anything and everything space and science. Wouldn't that be fun?

Andy Weir: Randall Munroe and I did... We're together at a Google event once. That was pretty cool.

Mat Kaplan: Really?

Andy Weir: Yup.

Mat Kaplan: Wow. I've never met him, but we've corresponded a little bit.

Andy Weir: He's cool.

Mat Kaplan: You talked about how that other hero, she never leaves the surface of earth.

Andy Weir: Stratt.

Mat Kaplan: Stratt. She manages to pull together humanity. The world does come together to battle its impending doom. For example, a lot of the action takes place on a Chinese aircraft carrier.

Andy Weir: Yup.

Mat Kaplan: People wonder if we will be able to find the same unanimity in the real world if we ever face a similar global catastrophe like let's say avoiding the impact of a giant asteroid. That might be the best example. Do you think that we have it in us to come together the way they do in your book?

Andy Weir: Absolutely. Not only do I think we have it in us, I think we would definitely 100% do it. Because these fictional scenarios are not vague, long-term difficulties like climate change. I'm not poo-pooing climate change. I'm just saying that that's not a thing that you can definitively say, "Look, every human being is going to die as a result of this. We need to deal with it." Climate change is like some species that are probably going to go extinct and buildings along the shores might end up becoming non-habitable.

Andy Weir: You might not be able to grow wheat in this area anymore, so you have to grow barley, or something like that. And it's hard to get people to care a lot about that. But if you're talking about like an Armageddon or Deep Impact scenario where it's like, "Oh yeah, see that big rock in the sky? That is going to come kill us and it's going to happen on Thursday, March 9th," something like that, then you can absolutely expect all the world to work together.

Mat Kaplan: As we talk about this, the world is in the midst of the Planetary Defense Conference. It'll be over by the time people hear this. They are actually people trying to consider this stuff. I supposed there's a bit of the frog in the pot scenario here.

Andy Weir: Well, for climate change certainly. But for Project Hail Mary, it's another one of those... Everyone on earth understands the idea, if the sun gets dim, we are all going to die. They get it. It's like plants need the sun. And without plants, we die, and so on. Again, it's one of those scenarios where it is not arguable. It's not like climate change, which is a slow erosion of our environment in ways that are damaging and bad, but aren't going to end the species. This is like, within the fictional context, this is an indisputable threat.

Mat Kaplan: We won't say how it all comes out. You may be able to guess, but I will tell you, you'll have great fun getting there. It happened with The Martian. You told me that it was underway with Artemis. Have you heard from anyone who wants to turn Project Hail Mary into a movie, because I'd be first in line?

Andy Weir: Yes. It's plugging along. MGM bought the film rights. Bought them outright. Didn't just do an option, which for who don't know the film industry, just means that ordinarily when a studio options a book, they give you a small amount of money. Well, small for a studio, large for me. They give you a small amount of money to reserve the rights. They haven't actually bought the rights yet, but they're just giving you that money and it means that for the next 12 months or 18 months, whatever the contract says, you're not allowed to sell the rights to anyone else.

Mat Kaplan: It's like a non-refundable deposit.

Andy Weir: Yeah, it's basically a deposit. You actually work out the entire rights contract, including what they would pay to buy the rights from you in advance, and they and they alone have the option to buy the rights. They can buy the rights from you simply by cutting you the big check at that point. Now, MGM skipped that phase and just said, "We want to buy the rights directly," which is good, so they gave me the big check right away, which I like because money is awesome. And then we also have Ryan Gosling attached to play the lead.

Mat Kaplan: Oh wow!

Andy Weir: Which is awesome, because he has the same initials as Ryland Grace, so he could bring his own cuff links to set.

Mat Kaplan: That is a terrific choice. I think he's great for that part.

Andy Weir: He's ideal for the role. We have Phil Lord and Chris Miller set to direct, the directing duo. They're hot property in Hollywood. We have the illustrious Drew Goddard working on the screenplay. Now, Drew is the one who adapted the screenplay of The Martian. We like Drew.

Mat Kaplan: Good track record.

Andy Weir: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad we're talking about The Martian again because we got to talk about real space before I let you go.

Andy Weir: Well, is there anything interesting going on on Mars lately?

Mat Kaplan: I was going to ask you about that little helicopter, that little whirly bird. Don't you think having a living drone to play with might have helped Mark Watney pass the time?

Andy Weir: Probably would have. Yeah, probably would have. He's like, "This is fun. I'm not accomplishing anything." If you asked me a few years ago, "Hey, what do you think about a helicopter on Mars," I would have said that's the stupidest thing I've ever heard, because has Mars has less than 1% of our atmosphere. Those blades are going to be going absurdly fast. It's going to have to weigh like nothing. Well, they did it and it works.

Mat Kaplan: To paraphrase the great Jeff Goldblum, JPL finds a way.

Andy Weir: JPL, uh, uh, uh, finds a way. I could say there was a lot of ingenuity in the design of that helicopter.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, one might. How do you feel about other stuff that you're seeing? We have a contract that's been awarded, although it's been contested, to take a really big spaceship full of people to the moon. Maybe they'll build a little town there. I think I know what they got to call it if they do.

Andy Weir: It's what they called the program. It's the Artemis program.

Mat Kaplan: That's true, yeah. What do you think? What do you think of our status?

Andy Weir: I'm excited, but the best I can get about major missions nowadays is cautiously optimistic, because NASA's priorities keeps changing and changing. Not through any fault of their own, it's just that it changes every administration. However, the previous administration and the current administration are both game to go to the moon. It's kind of nice for NASA to not have a massive shift in priority with a change of administration. Maybe they can seize on that and make some progress in one direction for a change, rather than being told to go back and forth and stuff like that.

Mat Kaplan: That's something a lot of us are keeping our fingers crossed about. What's in store from that wildly inventive mind of yours?

Andy Weir: Well, I'm already working on my next book now. I'm working on the set up for it. I'm doing the research and stuff. I don't tell anybody publicly what my plans are until I'm sure that I'm going to write that book. Because sometimes I'll get a few chapters into an idea and say like, "I don't know. This isn't working, or maybe another idea is better." I don't want to tell everybody I'm working on something and then not do it.

Mat Kaplan: Didn't you tell me once though that you have scores of potential books tucked away from there?

Andy Weir: Yeah. I've probably got more ideas than lifespan to write them. Some of the ideas turn out not to work. I'll write a few chapters and I'm like, "This isn't as cool in reality as I thought it was going to be when I envisioned it. This is not the book I'm going to write right now." And then other times it'll be like, yeah, I put work into it. It sucks and I set it aside, but then I strip it for parts later. I take something, which is the case with Project Hail Mary.

Andy Weir: Some elements from Project Hail Mary came from a failed book that I was working on called Czech. I was working Czech after The Martian and before Artemis, and it didn't work out. I put it on a back burner, or I actually put in the refrigerator, whatever you want to call it. But there were a couple of nuggets of awesomeness in Czech that I stole for Project Hail Mary. One of them is Stratt is based directly on a character that was in Czech. She was kind of imported from Czech. Also, astrophage is very similar to... In Czech, it was an alien technology.

Andy Weir: In Project Hail Mary, it a naturally evolved life form, but astrophage is very similar to a MacGuffin that was in Czech. I'll strip it for parts and say like, "Okay. This, this, this, and this are cool. I'm using that. The rest of the story sucks. It's staying in the fridge."

Mat Kaplan: Every time we talk I think, God, it can't possibly be as much as it was the last time, but it always is.

Andy Weir: Ah, thanks, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: No, thank you. And thanks for this outstanding book that I recommend very, very highly.

Andy Weir: Thank you so much.

Mat Kaplan: Andy Weir is the software engineer who's somewhat successful hobby is writing terrific bestselling fiction that leads to smash hit movies. His latest novel, the one we've been talking about, is Project Hail Mary. It has just been published by Ballantine Books, and we'll be giving away a copy when Bruce Betts arrives in moments with his new What's Up Space Trivia contest. That's it.

Andy Weir: End scene.

Mat Kaplan: It's time for What's Up on Planetary Radio. Here is the chief scientist of the Planetary Society Bruce Betts. Welcome back. Welcome for number 1,000. This is the thousandth Planetary Radio episode.

Bruce Betts: That's stunning. Stunning. And a thousand for you. It's only 950 something for me.

Mat Kaplan: But you were there at the beginning, so I think that this is an anniversary that you can celebrate as well. I hope everybody is celebrating. Where's my cake? I mean, all you have to do is hang in there for 18 and a half years.

Bruce Betts: And produce one every week with almost no repeats ever. Oh, by the way, I had a Space Policy Edition once a month. That's all you have to do.

Mat Kaplan: That's so dumb. Why would anybody do that?

Bruce Betts: I don't know. Speaking for all the listeners and the people at the Planetary Society, we are so grateful that you are that dumb. Thank you, Mat Kaplan.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. I can assure you, I'll keep it up.

Bruce Betts: Way to be dumb. We can count on you.

Mat Kaplan: Just like we did 1,000 episodes ago, tell us about the night sky.

Bruce Betts: It's identical to that first episode. Would you believe? No, it's not, but it's a planet party to celebrate to a thousand episodes. If you're lucky and can see really low to horizon, you can actually pick up all five naked eye visibile planets between the evening and morning sky. In the evening, we've got Mercury making a nice apparition for Mercury in the evening west low down, but much lower is super bright Venus.

Bruce Betts: That's one that you're really going to have to have a clear view to the horizon soon after sunset, but Venus will be coming up and be bright and partying later on. Check out Mercury. If you want to see the crescent moon playing with the planets, on the 12th, it will be near Venus. On the 13th, near Mercury. And on the 15th, a little higher up also in the southwest will be Mars. Mars is hanging out near Gemini's feet right now. Kind of stinky. But wait, don't order yet.

Bruce Betts: If you're picking this up soon after it came out, check out the Eta Aquariids meteor shower on May 6th and 7th. Particularly good if you're on the southern hemisphere, so that peaks the night of the 6th and 7th. Good few days before and after. And just preview, we'll talk about it more next week, total lunar eclipse coming May 26th.

Mat Kaplan: I was just thinking, when you said that the sky is exactly the same as it was a thousand episodes ago, it would be kind of as if we were the Mayan calendar and it's all just this great circle of life. I love that concept.

Bruce Betts: As you've done so many times to me over all these episodes, I am stunned. I have no response, so I'll just move onto this week in space history. It was 60 years ago this year Alan Shepard become the first American in space, and it was 2003 that Hayabusa launched on its way to sample an asteroid.

Mat Kaplan: Big week.

Bruce Betts: Onto random space fact.

Mat Kaplan: Number 1,000 for that too.

Bruce Betts: Pay tribute to Michael Collins, who passed this last week. Of course, Apollo 11 astronaut, but he was also the first person to perform two space walks or two extravehicular activities, EVAs, both during his Gemini 10 flight. One was a stand up EVA, so he stood up and took pictures, and the other went with an umbilical over to the Agena Target Vehicle they had rendezvoused with, which also made him the first person to travel between two vehicles in space.

Mat Kaplan: Very, very accomplished man and quite a great artist too. I'm only sorry that I was never able to have him on the show. Judging from all reports about him, he was a really just decent good guy.

Bruce Betts: Yes. He'll be missed. We move on to the trivia contest. Apparently in an attempt to confuse people again accidentally, I asked you, what is the only IAU constellation whose name is derived from a geographical feature on earth? How did we do? Although I know how we did, how did we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to start with this from Gene Lewin in Washington. He wrote us this lovely long poem. We only have time for the last stanza, and I'm going to read it because it provides the answer I think you're looking for. Lastly, he chose a mountain, assigning this terrestrial label, overlooking Cape Town. It is Mensa or the Table. Yeah?

Bruce Betts: Yes, indeed. The constellation Mensa, Latin for table, was named after Table Mountain in South Africa where 18th century French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, sorry, I can't pronounce French, named several constellations in the southern sky after instruments and things. He named that one after Table Mountain and it got shortened to Table, but it was originally known as Mons Mensae or table mountain.

Mat Kaplan: And a couple of listeners were aware of this that apparently there was a terrible fire, forest fire, on Table Mountain in South Africa. I believe it has been extinguished now, but really, very destructive in the beautiful state part there. We were sorry to hear about that, but interesting that that would come up right now. A whole bunch of people also gave us Eridanus. You said it had to be one of the 88 IAU recognized constellations, right?

Bruce Betts: Yes, I did.

Mat Kaplan: Eridanus, too many people to mention said, is a river mentioned in Greek mythology but is also the name given to a real underground stream near Athens in Greece. Would you have accepted this?

Bruce Betts: Do I need to know?

Mat Kaplan: No, you really don't, because our winner...

Bruce Betts: I would be inclined not to accept it, to be honest, but it's so close that, yeah, I would have accepted it. But that was named after the mythical river rather than being named after the earth feature, at least that's my understanding. That one's a lot harder to sort out because it was named by the Greeks 2,000 more years ago as opposed to the 18th century when we know the story of it. Sure, but I would have slightly accepted that.

Mat Kaplan: Fortunately, we are saved from that controversy because Random.org in its wisdom chose a first time winner, Al Pierce in Oregon, who said Mensa. He didn't explain all the Table Mountain stuff, but I think Mensa was good enough, right?

Bruce Betts: Yes. Yes, it was.

Mat Kaplan: Congratulations, Al. You are going to get a copy of the Mars pocket Atlas from Henrik Hargitai and the Central European Hub. We've bene talking about it for a while now. I think we're going to give one more copy away next week, because we have a new prize to announce this time. I'll say it again. It is gorgeous. It's a real travel atlas, and I'm guessing, Alan, that you will get a little overlay of the State of Oregon that you can use to judge the scale of stuff on the red planet. Congratulations.

Bruce Betts: Congratulations.

Mat Kaplan: And there's more.

Bruce Betts: Oh, there's more? This time there's more. Excellent.

Mat Kaplan: Keith Pratt, whilst being a member of Mensa, the association of geniuses, which I'm not a member of, are you?

Bruce Betts: I can neither confirm nor deny whether I'm a member.

Mat Kaplan: I'll watch for the secret handshake. He says, "Whilst being a member of Mensa," he's from the UK, "gives you bragging rights, being a member of the Planetary Society is much better. Love the podcast."

Bruce Betts: Yay!

Mat Kaplan: Mark Neshelsky in California. He says, "That's great. Wonderful constellation." He says though he'd rather have this guy commemorate an air pump.

Bruce Betts: Congratulations, they did. Same person, but it was just a generic air pump rather. I mean, maybe it was the astronomer's air pump. I don't know.

Mat Kaplan: Finally, from Dave Fairchild, our poet laureate in Kansas, "Mensa is a constellation near the souther pole. It was named for Table Mountain, African, I'm told. It's not much to look at and its stars are very faint. The large Magellan cloud is in it, famous though it ain't.

Bruce Betts: Well, it is now.

Mat Kaplan: Much more so than ever before in its entire history. We're ready to go on.

Bruce Betts: Back to Michael Collins. On Michael Collins' second EVA, what did he collect from the Aegina Target Vehicle, and what unrelated item did he lose during the EVA? I'm looking for two things here, one thing he collected from the Aegina Target Vehicle, the other he just lost in space.

Mat Kaplan: You have until Wednesday, May 12th at 8:00 AM Pacific Time to get us this answer and you might just win a copy of that terrific book, Project Hail Mary, by who else, Andy Weir that you've just heard Andy and I talking about. It's that good, folks. It is that great a book, and it is now available from all the usual places.

Bruce Betts: Who's that third character?

Mat Kaplan: I was so reluctant to talk about it. I wanted to leave something for people to discover. I think people probably figured out that he's not from around here, but he's just great. He's beautifully realized.

Bruce Betts: So it's not you?

Mat Kaplan: No, it's not me. I wish it was. It's kind of a buddy picture is what it will be when it becomes a movie. I will say no more. It's absolutely delightful.

Bruce Betts: We can star in the buddy picture.

Mat Kaplan: You and me, absolutely. I'm going to Ryland Grace. I'm going to be the human.

Bruce Betts: That sounds ominous. All right, everybody. Go out there. Look out for the night sky and think about circling the moon alone in a spacecraft for a while. Thank you and goodnight.

Mat Kaplan: Apparently, it's a very peaceful existence for those few hours or days, as you circle in the command module. I'm ready to go. He's Bruce Betts. I don't know if he's ready or not, but he is the chief scientist of the Planetary Society, who joins us every week here for What's Up. Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its members. Members or not, don't forget to give us an Apple Podcast rating or review.

Mat Kaplan: Mark Hilverda is our associate producer. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth