Planetary Radio • Feb 28, 2024

The legacy of Red Rover Goes to Mars

On This Episode

Courtney Dressing

Associate Professor in the Department of Astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley

Abigail Fraeman

Deputy Project Scientist for NASA's Curiosity Rover

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Over two decades ago, an innovative partnership between The Planetary Society, NASA, and LEGO created the Red Rover Goes to Mars program. Today, we reflect on the program's remarkable achievements with our chief scientist, Bruce Betts. We're also joined by two extraordinary people whose lives were forever changed by their experiences as student astronauts in the program during their high school years. Courtney Dressing, an associate professor in the Department of Astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, and Abigail Fraeman, the deputy project scientist for NASA's Curiosity Rover at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, share their inspiring journeys through the program and beyond. Then Bruce Betts returns to share more of LEGO's involvement in space exploration and a new random space fact.

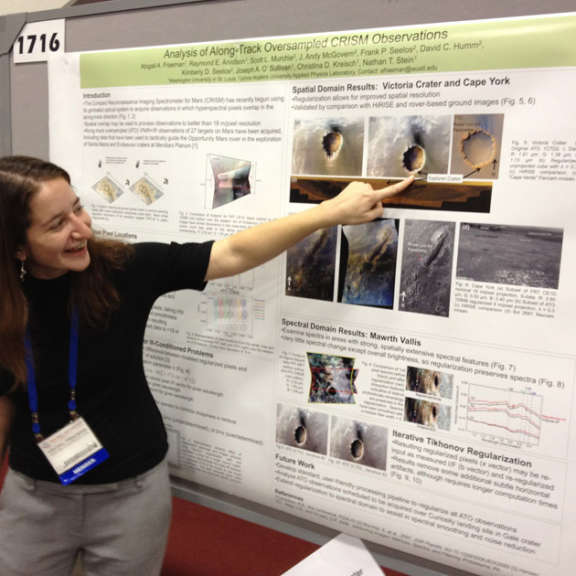

The central image is an Astrobot, a LEGO minifigure representation suited up for space. The Astrobots told their stories to the world. Other features include magnets in the central oval to collect Martian dust and colors to study color appearance under the Martian sky.

Image: The Planetary Society

Related Links

- Red Rover Goes to Mars

- Red Rover Goes to Mars Spacecraft DVD

- Mars DVD Code Clues

- Planetary Radio: The 20th landing anniversary of Spirit and Opportunity

- Planetary Radio: A Fond Farewell to Spirit and Opportunity

- Mars Exploration Rovers

- Watch Good Night Oppy

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- Register for Eclipse-o-rama

- Experience the total solar eclipse with Bill Nye

- Register for The Planetary Society Day of Action

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We are celebrating the legacy of the Red Rover Goes to Mars program, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of the Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. Over two decades ago, a pioneering collaboration between the Planetary Society, NASA and LEGO created the Red Rover Goes to Mars program. It was aimed at captivating the public's imagination with Martian exploration. Today we reflect on the program's remarkable achievements alongside our chief scientist, Bruce Betts. We'll also be joined by two remarkable people whose trajectories were forever altered by their experiences as student astronauts in the program during their high school years. Courtney Dressing who's now an associate professor in the Department of Astronomy at the University of California Berkeley and Abigail Fraeman, who's currently serving as the deputy project scientist for NASA's Curiosity Rover Mission at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. As we delve into their experiences, we'll uncover the program's profound impact on their lives and careers. Bruce Betts will return at the end to share more of LEGO's involvement in space exploration and a new random space fact. If you love planetary radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. Here's Dr. Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of the Planetary Society to tell us more about Red Rover Goes to Mars. Hi Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hi Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's been 20 years since the Red Rover Goes to Mars program and the student astronauts got to go to JPL and watch Opportunity Land. That is so wild that this program that's been so near and dear to the hearts of people at the Planetary Society happened that long ago.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, you think it's weird for you. It's very weird, but it took a lot of effort over many years for the Planetary Society to execute the whole program.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I could explain what it is, but I'd rather hear it from someone who was working on the program at the time. What was the Red Rover Goes to Mars Program? It encompassed so much.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, that's a tough one to answer, even though I managed it for the last few years of its existence, because it did have so many aspects to it, fundamentally it's a program the Planetary Society did in partnership with the LEGO Group, LEGO in all caps, and it was do a whole broad suite of educational related activities tied to what ended up being Spirit and Opportunity, originally, it was tied to what were going to be the Mars 2001 lander and an orbiter and those were canceled, following the failures in '98, '99. So that caused the program to stretch out, but it was actually, officially part of the mission, the Spirit and Opportunity Missions, and it was an activity that was completely funded by Planetary sighting members in LEGO. And we did a whole bunch of activities to engage the public, which is what we try to do with space exploration. One Piece, a non-trivial piece was the international competition that chose the student astronauts that were 16 students from 12 countries and they win, through JPL for the first few weeks of the mission and worked with the mission and worked with the mission data, but we also had a lot of other pieces that I'd be happy to tell you about. In summary, it's trying to engage the public, do both public education, working with students and do good stuff tied to those missions, and I think we did in the end.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How did the Planetary Society first become involved in this program?

Bruce Betts: That even predates me. That was heavily tied to Lou Friedman, our executive director emeritus and him working with Wes Huntress who was the head of space of science at the time at NASA. And then, it became this huge sprawling beast. So, that's why I took over managing with just a whip in a chair and trying to contain the beast and it turned into just an awesome pet.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you're one of those people that is so passionate about educating kids about space, whether it's through your children's books or the huge role that you play in our planetary academy, our membership program for children, but this I feel was a program that really directly impact the lives of these student astronauts that got involved and we're going to be hearing from two of those students in a little bit, but what was that like for you, interacting with these kids and seeing how this impacted them?

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it was an interesting program just as background, so hopefully, we'll discuss, we did a lot of activities that were affecting a lot of people at a lower level, but engaging a lot. And then, we did these activities like student astronauts. They were very intense and a lot of effort for a few students, although as you know, at least, well, multiple of those 16 went on to careers in space science or working in space science reporting in one case and it was really great. They're just ... they're an amazing set of people so into it and so enthusiastic. It just was very rewarding. It still is.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So as part of this program, we worked with the LEGO group. What did that collaboration contribute to the program?

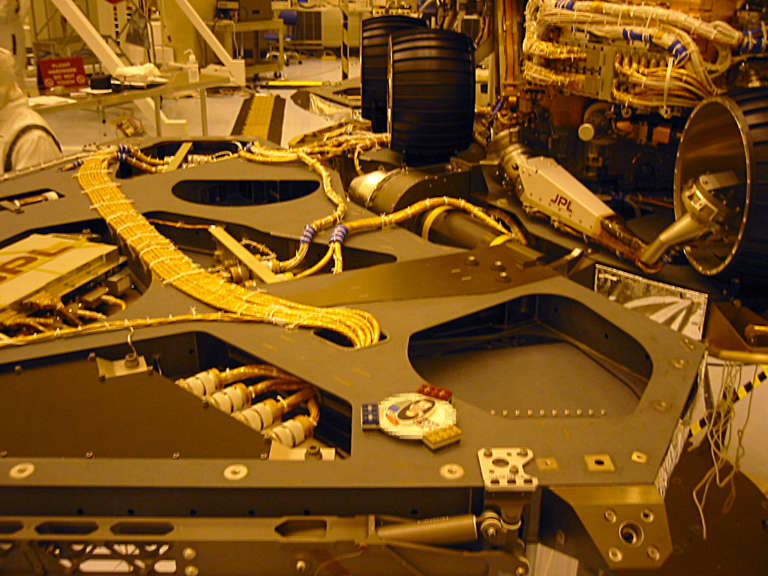

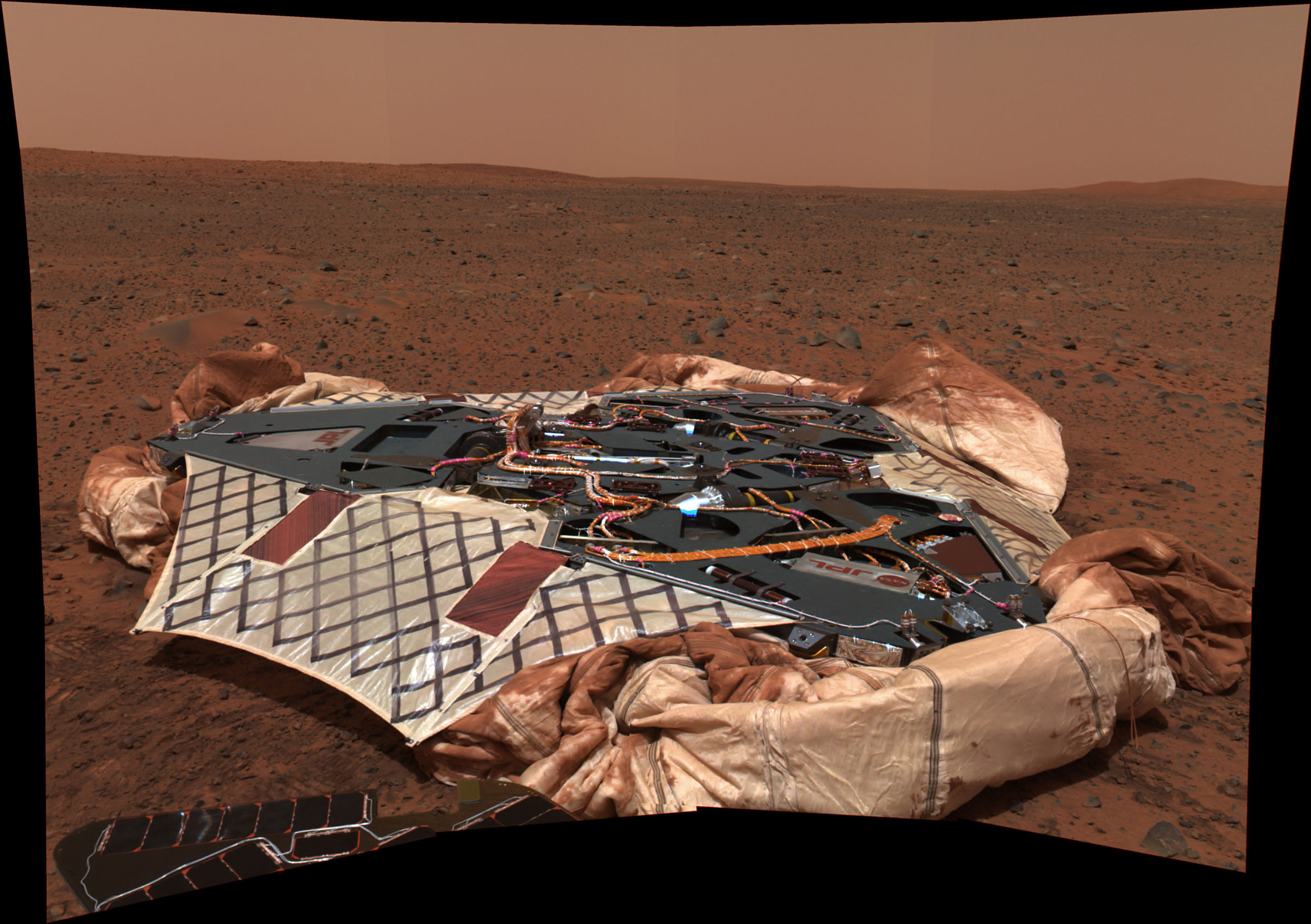

Bruce Betts: Funding was a major source, but also their input. So we did things, a lot of things literally in partnership with them. So we actually, along with LEGO, they did some of the publicizing and we did the publicizing and all behind the scenes on getting the names of the rovers. NASA made the selection of course, but Spirit and Opportunity came from a contest that we ran with LEGO, I worked with their first LEGO League where kids build rovers and this kid ... they have a different theme each year and they did a Mars Rover theme, so we worked with them on refining kind of the science behind it. We have silica glass DVDs that we sent to Mars and NASA working with us and LEGO, we collected four million names of people who want to send their name to the surface of Mars. And they're contained on silica glass mini DVDs and there's a frame around them and that frame has LEGO, what look like LEGO bricks, although they're aluminum because they bake these out to kill any critters on them, so your LEGO bricks don't do very well. Then, it had Astro Bot, a LEGO mini figure representation on it, and we had them write blogs in the early days of blogs, and we ran a contest to name them. So one was Biff Starling and the other was Sandy Moondust and they wrote blogs and they also wrote in the magazine, the LEGO magazine, which has a huge distribution. So a lot of things like that. They also, by the way, appeared on Planetary Radio two or three times back in the day and they're very fascinating personalities. They're still hanging out on Mars having a great time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You didn't happen to have anything to do with their appearance on Planetary Radio, did you?

Bruce Betts: Well, I mean I may have been involved in a rather deep way.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, I need to find these older episodes of you and Jennifer Vaughn, who's our chief operations officer, doing these voices, because I know we must've done some kind of reverb on them or something.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Yeah. Matt did some serious processing and Matt interviews them and it's just a very different take on Planetary Radio.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As I was going through the office with one of our upcoming guests, Abigail Fraeman, we have a modeler, we have a copy of this silica glass disc with Biff on the front and we were talking about it and I looked at it and as a fan of the LEGO movies, in my heart, I want to think that Benny, the Starship, LEGO guy from the movies is in some part a spiritual successor to these Astro Bots

Bruce Betts: I think that makes sense. I should say they actually issued mini figures, LEGO mini figures of Biff and Sandy and those exist. They're rather collectors' items now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You said that these discs were made out of silica glass because we needed to sanitize them, but I imagine that helps with the longevity of them surviving on Mars.

Bruce Betts: Yes. That was the other-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Where are they now?

Bruce Betts: The other point, they are sitting at the landing sites, so they were actually attached, not to the rovers, but to the landers. So they landed with the crazed bouncing airbag system and then the tetrahedron opened up and they drove off the tetrahedron flattened and they're mounted on that. We have pictures of them from Mars before the rovers drove away. So they're right at the landing sites. They have friendly little comments to anyone who finds them. Rough calculations are that they should exist for at least 500 years in a format that one could figure out how to read it. By the way, I don't know that you notice, because the one in the office doesn't have the secret codes. It just has a representation, but we had secret codes on both of the discs. It was another activity, so people in the codes were really into it, and we had one that was very relatively simple to figure out, one that was not simple, and we gave additional information on our website, because there wasn't that much on there. So anyway, we tried to figure out, well, how could we use every square centimeter or millimeter of the frame and the disc to do something interesting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Actually, as a personal exercise, I wanted to go through and see if I could actually crack the codes on these, and I found the little hints that were on our blog. Pretty helpful because it was, that second one was a very complicated code and I liked that-

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's brutal.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's so brutal. I like that people can go back and still engage with that and try to figure it out themselves and yeah, I can link those webpages on our episode page for this episode of Planetary Radio because who doesn't love cracking puzzles? I've spoken to people about this in the past, but there was a particular Planetfest that was really kind of wrapped up in this. It was the Wild About Mars celebration. What was that like?

Bruce Betts: That was super cool. Planetfests are the equivalent ... are amazing, especially when things work because it's the opportunity to have thousands of people with you now combined with people out virtually, when you're waiting with the drama of whether these things survive down to the surface. So, you live through it with all of the people in the cheering, weeping in 98 or 99, but that's the only Planetfest I haven't been to. So as long as you invite me to them, I think we're okay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So the rule is invite Bruce to the Planetfest, not to the rocket launches.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, exactly. Yeah, and it was great because we got people from the mission came and talked to the group and we had student astronauts there, the ones that were around and we had a lot of presentations and talks, but fundamentally, it was about pumping in the JBL NASA feed on a giant screen and watching and experiencing it altogether and seeing those ... in the case of those rovers, the successful ... not only successful landing, but images coming in. NASA never promises the images, which is crazy making when you're trying to plan one of these, but they always pretty much come through. You get something and that's super exciting. So every time we've done that, it's fabulous and Wild About Mars was a little play-on words because Stardust spacecraft flew through the coma of P/Wild 2, Wild 2 comet the day before. So we actually focused on it on one day and on spirit the next day.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I cannot wait to go to one of these Planetfests in person. The only one I've experienced was our virtual Planetfest. Doing it in person would be next level.

Bruce Betts: It is next level, but on the other hand, all sorts of people get to participate in the virtual, the camp slip out to wherever we are, which is usually in Pasadena, although not always, but usually tied to ... especially if it's a JPL mission. We've also done things with APL in Maryland and elsewhere. So yeah, so it was a whole lot of good stuff and it stood the test of time and now, you're interviewing former student astronauts who are leaders in the Planetary community now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's just one more example of the ways that these programs that we've had going for almost 45 years now have made these huge impacts on the space community over time. And yeah, there were only a certain number of students that were selected for this program, but when you talk to them, the way that it changed their lives is just so amazing. Well, thanks for sharing this, Bruce and for playing such a big role in this program, whether it was the single students that had their lives impacted or just all these other people that got to feel involved, and the people that got to feel like they had a role in naming the Spirit and Opportunity Rover. This program did so much, and that's just so cool. Well, I'll talk to you again later in this episode, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Yay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: See you soon. Now we'll hear from Dr. Courtney Dressing. One of the student astronauts in the Red Rover Goes to Mars program. Courtney is an observational astronomer who focuses on detecting and characterizing planetary systems orbiting nearby stars. She's an associate professor in the Department of Astronomy at the University of California Berkeley, where she holds the Watson and Marilyn Alberts chair in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, also known as SETI. Our senior communications advisor, Matt Kaplan, captured this moment with her at Planetary Society Headquarters during our recent Search for Life Symposium.

Mat Kaplan: Courtney, welcome back to the Planetary Society, 20 years. Can you believe it?

Courtney Dressing: I really can't believe it. Thank you so much, Mat. It's wonderful to be here. I can't believe it's been two decades.

Mat Kaplan: Let me read you something that I found. This press release international student team selected to work in Mars Rover mission operations, and guess who wrote it? Mat Kaplan. The Planetary Society has chosen 16 student astronauts to work with the Mars Exploration Rover team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory when the Twin Rovers touched down on Mars in January of 2024. This was November 6th, 2003, so even more than 20 years ago, and sure enough, scroll down a little ways, and there's Courtney Dressing. So a lot has happened since then, but what I'm really curious about is what role did that play in setting you on the course, the very successful course that you are on now?

Courtney Dressing: I think of that experience all the time, and I think it's fair to say that my career would not be what it has been without having been a Red Rover Goes to Mars student astronaut. I got to go to JPL and live on Mars time and see how missions actually work. I think one of the best things I learned from that experience is that it really isn't just one person. It's teamwork and it's global cooperation that helps us explore the universe. I had always been interested in space and I was interested in reading about the space shuttle, memorizing the names of astronauts and learning all these facts about our solar system. Red Rover Goes to Mars was the first time where I felt that I could be part of the team to make those discoveries, not just someone reading about that from home.

Mat Kaplan: And you saw that as part of this team of students, right? I mean, did it become a fairly cohesive group that they'd come from all over the world, right?

Courtney Dressing: It was a wonderful team. We had people from all around the world. My partner was from Brazil, and I enjoyed talking with him and learning about his experiences and his interest in space.

Mat Kaplan: Now, sadly, even though we called you student astronauts, we didn't get to send you into space. Maybe today we'd have pulled that off, but 20 years ago, no. What did that mean?

Courtney Dressing: I think it sounded like a really cool title, student astronaut. It was very impressive. My guess is that it's because we were exploring together and we were pretending that we were on Mars alongside the rover, and honestly, some days it felt like we were, because the data quality was just so exquisite.

Mat Kaplan: What did they actually have you doing at JPL?

Courtney Dressing: We were shadowing primarily so we would be present in the room when major events happened. I remembered standing near the table looking at the map where Spirit was supposed to land. As the scientists and engineers discussed where they thought the rover would end up, we also took notes about what we saw and we wrote blog entries to share with the world about our experiences. Later on, we also helped calibrate images of the sundial on the rover to help track the dust contamination over time.

Mat Kaplan: That's already more than I thought you got to do, because I would thought you were going to stop it. We shadowed these scientists, but they actually were letting you work with some of the data in a sense.

Courtney Dressing: We got to do some of the work with the data in the end. Not super technical things, but one of the student astronauts later ended up working at JPL as a Mars scientist and still does.

Mat Kaplan: Was that Abi?

Courtney Dressing: Abi Fraeman.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Yeah. Another great success story. Out of that project from the society, where were you staying at the time? I mean, were you with the other people or at a home?

Courtney Dressing: We were staying in ... I think they were a seminary lodging situation. Each of us got to bring a parent or guardian because we were all young. So my dad came out with me and he would drive me to the jet proposal laboratory in the middle of the night, which was very kind of him.

Mat Kaplan: Good dad.

Courtney Dressing: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: So you left that experience, I mean, how did it change your thinking about what you wanted to do with your life?

Courtney Dressing: I had been interested in being an astronaut since I was a kid. I had an eye injury in high school and that took being an actual astronaut off the table, but I still wanted to explore the universe and this experience that the Red Rover Goes to Mars student astronaut taught me that I could and it gave me the confidence to go on and then apply for more research positions, I ended up majoring in astrophysics in undergrad and in graduate school. I came back to the Pasadena area for a postdoc, and now, I'm a professor at UC Berkeley. And I think without that experience at JPL, I don't know if I would've realized that that was a path I could actually pursue.

Mat Kaplan: What is the name of that chair, that endowed chair that you occupy at Berkeley?

Courtney Dressing: I am the Watson and Marilyn Alberts chair for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

Mat Kaplan: Which is very impressive sounding. I mean, anybody who's in an endowed chair has an endowed chair. That's pretty impressive. What do you do now on a day-to-day basis? Tell us about your research.

Courtney Dressing: I really love my job. One of the most exciting things I'm working on is that I am co-leading the science team for the upcoming Habitable World's Observatory. This is a project that would launch after the Roman Space Telescope, which would be the successor to the James Webb Space Telescope. I also, as a professor at Berkeley, teach classes every semester. I work with undergraduates and graduate students, and my group at Berkeley is currently analyzing JWST data of a hot Neptune sized planet. We're also measuring the frequency of planetary systems around M Dwarfs and investigating habitability,

Mat Kaplan: Which explains your wonderful earrings, which I assume are not made of beryllium.

Courtney Dressing: No.

Mat Kaplan: Let's talk more about the HWO, the Habitable World's Observatory. I'm just blown away. I just hope that I'm still in a position to talk to people about this stuff. When we see that follow on to these other great space telescopes happen, is it exactly what is in the title? It's going to show us these worlds that just might have something living on them.

Courtney Dressing: I think it's even more than what the title says. So Habitable Worlds Observatory to many people sounds like a mission that is only going to focus on planets like the Earth, but Habitable Worlds Observatory will also discover hundreds of planets that are more similar to Jupiter or Saturn, and it will do transformative general astrophysics and study the planets in our solar system. So while one of the leading science cases is directly imaging planets like the Earth orbiting stars like the sun, that is just the tip of the iceberg of what HWL will do for science.

Mat Kaplan: What kind of timeframe are we talking about? We know how long it took to do Hubble and JWST. What is the status?

Courtney Dressing: So right now, we are actually in what we refer to as pre-pre-phase A, which is NASA jargon to say that this is before the mission has entered the stage of having a formal project office, and one of the recommendations that came out of a recent National Academy survey was to restructure how NASA does large space missions to try to make sure we do a lot of planning and careful thinking ahead of the time before we start setting up a big team and spending lots of money. So we're learning from our experiences with past flagships and we're doing everything in a very thoughtful, careful manner this time. Not to say that it wasn't thought for, it definitely was-

Mat Kaplan: We were feeling our way.

Courtney Dressing: Yes, right. We're learning more about how to do these big projects with teams of thousands of people. For HWO, we expect that the mission would begin in the 2040s and before you think that that sounds too far in the future, that is less time in the future than when I was a student astronaut in the past.

Mat Kaplan: That's a good point. Yeah. So you said you're basically coordinating the science that we hope to get from this incredibly powerful new instrument. What does that mean? Does that mean you're working with other scientists and we're saying, well, we'd like to do this?

Courtney Dressing: I'm on a team called the Science Technology Architecture Review Team or START. NASA Loves acronyms.

Mat Kaplan: Clever.

Courtney Dressing: And along with my co-chair, John O'Meara, who's at Keck Observatories, we're leading a team of about 20 people who are then advising a larger team of about 800 people to think about all of the science that we could do with this observatory and map that onto the kinds of technical requirements we would need to have. And then, there's a parallel group of engineers that's being led by scientists and engineers at NASA and JPL.

Mat Kaplan: So 15, 20 years, maybe we see first light and this thing starts to do its work. I sure hope that I'm in a position to enjoy that data, that light when it starts to come through this new mighty instrument. You will still probably ... well, you'll be a senior authority I would assume by that time, but it sounds like something that you'll be able to look forward to working with.

Courtney Dressing: I'm very much looking forward to working with the observatory, and I suspect that I will still be a professor at that time and probably nowhere close to retirement.

Mat Kaplan: Let me take you back to the start. When you were that 16-year-old getting exposed to all this stuff, did that also have an effect on how you want to communicate what the boss calls the passion, beauty and joy, the wonder of all of this to young people?

Courtney Dressing: My experience as a student astronaut definitely did cause me to think more closely about science communication. I really appreciated the chance to be behind the scenes and now, that I'm in more of a leadership role, I want to be sure that we bring in students and amateurs from around the world to participate in these missions. One of the things I'm most excited about for the Habitable Worlds Observatory is that we have a whole group that's devoted to mentorship and communication and diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility. So we want to be sure that this really is everybody's mission.

Mat Kaplan: I bet you the Planetary Society will want to help out with that part of the mission. Courtney, thank you so much. If you will, pardon me saying so, I think we're all very proud of you here since we had a little role in helping you get to where you are now. Congratulations on all of this and best of luck with all of these developments as they continue.

Courtney Dressing: Thank you. Thank you so much for everything.

Mat Kaplan: We hope it feels like a homecoming, coming back here to the society.

Courtney Dressing: It really does.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Just a few days after Matt's meetup with Courtney Dressing, I got to meet Dr. Abigail Fraeman, a fellow student astronaut in the Red Rover Goes to Mars program. Abigail is a research scientist in the planetary science section at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. She was previously the deputy project scientist for the Mars Exploration Rover mission before becoming deputy project scientist for NASA's Curiosity Rover. She's broadly interested in the origin and evolution of terrestrial bodies in our solar system, and her work concentrates on investigating how the complex geologic histories of Mars and its moons are preserved in their rock records. Hey Abigail, it's wonderful to meet you here at Planetary Society Headquarters.

Abigail Fraeman: Thank you so much for having me, Sarah. I'm thrilled to be here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Your life has been so changed by your experience with the Planetary Society and your involvement with this Red Rover Goes to Mars program and now, it's been 20 years and it's really cool to be able to actually look back and see how this program impacted people's lives.

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, completely. I mean, it's not an exaggeration to say that this program literally changed my life. It opened up a door to me about a world that I had no idea about before the program, this world of planetary science, and it showed me how incredible it was and 1000% directly inspired me to pursue this as a career. And the experiences I had through the Red Rover Goes to Mars program were really a motivator for me to keep going and continue ... when other things came up, maybe I want to do this more. No, nothing was as much fun as the fun I had as a student astronaut, and here I am 20 years later working on Mars Rovers at JPL. It's a dream.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What a life, but you love space long before that if what I've heard on the internet is correct, you fell in love with space as a kid when you were looking through a telescope at Saturn's Rings. What was it about that, that so impacted you.

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, internet in this case doesn't lie. Yeah, I've always really loved science and I watched a lot of Star Trek growing up, which made me kind interested in space, but really, what completely got me hooked was when my dad brought a telescope home one day and we set it up on the front steps of our house and this little red thing on the ground, and I looked through it and all of a sudden I was seeing the rings of Saturn and the fact that it was photons coming directly from that planet to my eyeballs, it wasn't a picture or anything, completely blew my mind. And there it was this tiny little planet with these tiny little rings and I was completely hooked.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's wonderful because even now as a full adult, when I see Saturn through a telescope, and I've been lucky enough to see it through some cool telescopes. I mean the 60-inch up at Mount Wilson is such a thing to behold when you look through, but every single time, I still get that feeling, I'm still a tiny child. I'm still in that space of absolute wonder and it blows me away every time I do it.

Abigail Fraeman: Wow. I'd love to see Saturn through 60 inch. Yeah, this was just like a three or four inch, a little tiny telescope, but even then, it's extraordinary and I love this space is accessible to everyone.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Did at that point in your life that you wanted to go into space science?

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, so I think after this experience with the telescope, I really started thinking, I wanted a career in space either as an astronaut, but in the case that didn't work out. An astronomer getting to look through telescopes as a profession sounded really cool to me. And so, I took a lot of what astronomy I could that was offered in my middle school, but I did science fair projects in middle school that were focused on astronomy. I joined my local National Capital Astronomers group and got really interested in the things that we can do here on earth to observe space.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How did you ultimately learn about the Red Rover Goes to Mars program?

Abigail Fraeman: So I was just Googling things. I was in high school, the internet was just becoming something that you could look into. I guess at the time it was in Google. I was probably on Alta Vista or something, but I was part of my high school's public speech team and I wanted to write a speech about space exploration and maybe Mars or something. And so I tried to learn more about space exploration and the history of space exploration, and I found the Planetary Society and all the wonderful material they had and then, saw this ad for this program where they were going to select people to go to JPL to see the Mars Rover landing. And I couldn't stop thinking about it and I said, I absolutely, absolutely have to apply to this. It sounds unreal.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I wish I had known about it when I was in high school because just applying would've been one of the most exciting things I'd ever done at that point.

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, the application was actually quite fun. I remember it fondly. We had to look at a picture of Mars and write an essay explaining if we were in charge of the rover, what would we want to do? And there was information about the different kind of instruments that you had and different constraints. This observation takes two hours, this one takes five hours, you have 24 hours, what do you want to do? What observations do you want to make and why? And it was such a fun essay for me to get to write

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And a cool thing that ultimately prepped you for a lot of your later career. So it sounds like, not even just the program itself, but even just the application was the beginning of this learning.

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, this morning I helped plan Curiosity Rover and I served in a role called the Long-Term Planner. So thinking what do we want to do with the rover in the next long-term? Obviously, it was a little bit more complicated than what I put into the essay, but same concept.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Through this program, you and a bunch of other students from around the world got to actually experience parts of the Mars Exploration Rover program. You talked a little bit about these planning phases and the fact that you got to go to JPL for it. What other things were opened up to you through this program?

Abigail Fraeman: I think there's a couple of things. The first thing was once we were selected as student astronauts, we had some time to work with Emily Lakdawalla who was helping coordinate the program to get us up to speed so we'd know what was happening when we were at JPL. She started Zoom sessions essentially before there was a Zoom to teach us online all about geology and what is an olivine and what is a basalt and what is remote sensing. And this was the first time that I'd actually had an opportunity to learn about these subjects. It's not something that gets taught in school very much. And I thought it was so cool. So, it really opened my mind to kind of the classes I could start to take when I got to college and that geology was actually an awesome field to study. The program also introduced me to Professor Jim Bell, who was the former president of the Board of Directors of Planetary Society. And through my involvement in the program, it enabled me to reach out to him after my freshman year of college and I said, "Hey, remember me? I was one of these student astronauts. Can I come work in your lab for the summer?" And so working with him was my first real taste of planetary science research.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Beautiful. I didn't even know you got to meet Jim Bell through that. What a moment. Then, me and most of the world, we experienced the opportunity landing either on TV or by watching it through the computer, but you got to actually be at JPL during the landing. What was that moment like for you and looking back on it, how did that change the course of your life?

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, I mean, when you have moments that are really important in your life, it doesn't matter how far away you get from them, you still remember them really clearly. Landing Night for Opportunity is one of those nights, I think I remember almost every moment and that night just kept getting better and better and better. It started off, we were with the science team watching the landing, Opportunity landed. It was so exciting. Then we got to go to the VIP area and I got to meet Bill Nye for the first time, who was a huge hero of mine, watched him on TV growing up, so that was the coolest thing ever. Then, we got to go be in the room with the press conference announcing the successful EDL, and the room was ... the entry descendant landing. The room was completely packed. It was so crowded and we were kind of pushed off to the side, and then the whole landing team just came bursting in chanting EDL, EDL and we got pushed out of the room. And then, I met the associate administrator of NASA who was standing next to me in the lobby because he couldn't fit in the room either. And it was just this wonderful excitement. The cherry on top of the night was after the press conference, we got to go back with the science team and wait for those first images to come down. And it was those images that just hooked it completely for me because they showed a picture of Mars that was unlike any other picture of Mars we'd ever seen. And it really showed me ... first of all, Mars is a place we can explore and there's so much we haven't seen. Here's something completely new. No human has ever seen it. And then second, being with the scientists, looking at the image and hearing them say, "I know what that is. I think that's this." I wanted nothing more than to just stay with them for the next three months and hear what they learned and learned how I could do that too.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of our look back at the Red Rover Goes to Mars program after this short break.

Bill Nye The total solar eclipse is almost here. Join me and The Planetary Society on April 7th and 8th for Eclipse-O-Rama 2024. Our can't-miss total solar eclipse camping festival in Fredericksburg, Texas. See this rare celestial event with us and experience a whopping four minutes and 24 seconds of totality. The next total solar eclipse like this won't be visible in North America until 2044. So don't miss this wonderful opportunity to experience the solar system as seen from Spaceship Earth. Get your Eclipse-O-Rama 2024 tickets today at eclipseorama2024.com.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: My coworkers and I recently, I guess it was about a year ago maybe, we all decided we want to go see the documentary Good Night Oppy together, so we all went down to a theater and when we saw the Red Rover Goes to Mars, students in the background with the matching red shirts, if there was a packed theater, we probably would've had to calm down a little, but instead, we all got to geek out and be very excited about it because look, there's our Red Rover Goes to Mars students. Did you see yourself in the background of that documentary?

Abigail Fraeman: I did, yes. Yeah, so there's the documentary that Amazon put out Good Night Oppy that tells the whole story of the mission, and I'm one of the people that they interview in it, and I told the story about what it was like being there on landing night and the film producers went through thousands of hours of archival footage and somehow in those thousands of hours, probably because we were wearing such bright red shirts, they did find just a few minutes of me that night when I was there in mission control, getting to see me, getting to see my fellow student astronauts who were with me, Shih-han Chan and Vignan and Wei Lin, so cool seeing that and just seeing our excitement and really remembering what that was like.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What was it like for the international students that you worked with?

Abigail Fraeman: I think it was just as exciting for them as it was for me. We all got to come out to California, and even though that was still in the United States, for me, it was still a big trip for someone who's 16, getting to go somewhere new and see something different. And we had a really good time talking to each other and learning about each other's customs. I was partnered with Shih-han who was from the UK. So, we had some fun comparing the way British people say things and people from the US say things, and I think we were all united by just our awe of what was going on and the fact that we could be a part of this.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That must've been a really beautiful moment for a lot of them because even to this day, there aren't as many opportunities for people in other nations to get involved in space exploration. So bringing these kids in, really igniting their imaginations and then, allowing them to go back must have been such a cool and formative experience. And it just fills me with such joy knowing that there are way more opportunities nowadays for people all around the world to get involved in this.

Abigail Fraeman: For sure. Yeah, and as our rovers are going on, we're having more and more international participation. The Curiosity Rover, something like 40% of our science team is from outside the US, so it's really important to inspire people not just in this country but in all of the countries because the best science is done when you have all these different people with all of these different experiences coming to the table and bringing their own perspective, you're going to get so much more out of it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've been thinking about that a lot in the context of the Artemis program, seeing all these new nations sign onto the Artemis Accords, every single new country that signs on just gives me so much hope for the future.

Abigail Fraeman: I agree. I think it's fantastic.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So after this life-changing experience, you went on to get your PhD in Planetary Science working with Professor Ray Arvidson who was the deputy principal investigator on Opportunity. So that, that's a really cool arc right there. Then you went and got your postdoctoral working at CalTech with Bethany Ehlmann, who's the president of our board of directors now. And then, after all of those amazing things, you ended up as the deputy project scientist for not only Opportunity, but also the Curiosity rovers. I just have to say right off the bat, that is so impressive.

Abigail Fraeman: Thank you mean. I mean, yeah, honestly, it's creepy how much it's all connected to Red Rover Goes to Mars, right? Because I met Ray, my graduate advisor when I was a student astronaut, but it was a very brief meeting. I remember celebrating, he had a birthday and we all ate cake up in Mission control, but when I was visiting potential colleges, I went to visit him because I knew he had this connection to the Mars Rovers because I had met him through the student astronaut program and we talked a lot and eventually, it didn't go there for undergrad, but I was saving it for grad school when I knew I could really get into research with him. So what a fantastic opportunity. And when I was visiting, he told me about his wonderful undergraduate student, Bethany Ehlmann. So I got to meet her later and I remembered, "Oh, you're someone that I'd heard about," and we became good friends and working with her as a postdoc was awesome. Then, yeah, of course, JPL has been my dream job ever since the Student Astronaut Program. So when I was out here for a postdoc, just knocking on everybody's doors saying, "Please hire me." So, to have the opportunity to not only work at JPL, but to work on opportunity that was still operating the time it took me to graduate from high school, get an undergraduate degree, get a PhD, do a postdoc, it was still going. So what a thrill to be able to be a part of that mission as a JPL'er. Unreal.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And that rover lasted almost 15 years. That is so far beyond the 90 days that it was planned, and a lot of that was due in great part to the people that worked on it having this wonderful ingenuity. Forgive me for that, but the things that your team had to do, driving the rover backwards, turning it off and on again. Singing little wake up songs every morning, not just to keep the rover going, but also, to keep everyone on the team feeling happy and motivated during the times when you weren't sure it was going to come back to life. That must've been such an intense but beautiful time in your life.

Abigail Fraeman: Absolutely, and this is part of what also makes working on Rover Mission so great. I mean, exploring other places is beyond thrilling, but the team that you get to do this with is equally, if not, more special. You get to work with some of the smartest, most passionate, most motivated people you'll ever meet, and it is such an honor to get to do that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It did last for 15 years, but ultimately poor Oppy eventually never woke up. What was that like for you and everyone else? I know that you came onto our show many years ago to discuss it, but what was that like?

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, I mean it was weird. So Opportunity was designed and Spirit to last for 90 days. And after 90 days, Oppy kept going and going and going. Six years in Spirit got stuck with solar panels pointed in the wrong direction, and winter came and there just wasn't enough power to keep Spirit alive, but Oppy kept going and going. So, at the back of our minds, you always know that someday it's going to end and it could be tomorrow and you never know. When that moment actually did come and we lost contact with Oppy and then many months later when we realized we weren't going to get contact back, it was like, "Oh, okay, it's actually happening." And the realization of what that means in terms of the people that you've been working with for me a few years, for some people two decades starting with the development, it's a big change. So, it's something that took some getting used to. Many people who worked on Opportunity and Spirit are still at JPL working now in Curiosity and Perseverance. So it's a wonderful legacy. It was also strange for me because through this whole arc of my career, Opportunity had always been operating as kind of this guiding pull to why I want to do planetary science. And so, having that suddenly not there, it was a little weird and something that I spent a lot of time reflecting on.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, happily, you were already also working on curiosity, so that allowed you to then continue on and just like its older sibling, curiosity is completely crushing it and living far beyond its expected lifetime, which is spectacular. That is so heartwarming.

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, I mean, I hope it doesn't sound heartless, but it really did soften the flow, having curiosity on Mars and man, I love that rover. I love working on the Curiosity Rover and the team that operates it and the science that we're getting to do with curiosity is so exciting. Curiosity has been going for a little over 12 years now. We're climbing this big mountain, looking at the history of habitability of Mars, and what's extraordinary about Curiosity is 12 years in, our science instruments are all still working. And we're still able to do the same depth of science we could do on day one, and the landing site just keeps giving. The higher we drive, the more spectacular things we find, and so it is just not getting old. I love it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's really cool that we can compare all these different locations now. I mean, there's so many worlds that we know so little about Uranus and Neptune, we've literally only flown by once, but with Mars, we can compare Gale Crater to Jezero Crater to Mariani platinum. All these locations that we've gotten to explore up close, and as you said, they're all so completely different, but the fact that Curiosity is now going up a mountain, seeing the way that all these layers of margin history has been just stratified and cast into the rock, it is such a beautiful opportunity for learning and then, comparing it to everything else. I can't even imagine what we're going to learn out of all this.

Abigail Fraeman: Yeah, I think we're just starting to scratch the surface. The cool thing about science is the more you learn, the more questions you have, and so we're able to ask so much better questions than we were able to ask 20 years ago when Spirit and Opportunity first landed, but we still have so many questions and we're just starting to kind of put together this time integrated history of the planet. I think one of the things that Spirit and Opportunity did was opportunity. They not only answered this question, was there once liquid water on Mars, but they found yes, and it was present in many different times and in many different environments there was hot water. There was acidic water, there was very neutral drinkable water. So now, we kind of want to know more like, okay, well, what did that history really look like? Were there periods where Mars was habitable and not what were the best places to go? And so that's what we're starting to do with Curiosity and Perseverance as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, we can't build a time machine, but that's about as close as you can get, even with the Earth. The only way that we can really piece together this mystery is by looking through the rocks and the way that our planet evolves over time. There's so much of that history that's just kind of lost to us.

Abigail Fraeman: Isn't that cool? I think that's so cool. We're detectives. We're history detectives.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's a beautiful thing. I've been thinking about that quote by Isaac Newton, "If I've seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants." And thinking about the fact that most of science history is literally just a legacy of people handing down their knowledge, teacher to student, teacher to student decade generation after generation. And this program sparked this thing that now allows you to go out and not only learn about Mars, but share it with other people. And I know that that was part of the legacy of this program. Part of the point was to inspire these student astronauts to then, go out and share what they had learned on their experiences. How do you feel like that mission to share what you've learned on Mars continues?

Abigail Fraeman: First of all, I think thinking about the legacy of the program and the mission is something we can start to do now, that we're 20 years out and the legacy of inspiration is one of the most important things that the mission and things the Planetary Society is doing is leaving behind. You go to screenings of the Good Night Oppy movie and there'd be people who just come up and say, your story is my story. I saw these things and they inspired me too, and I'm in a career in engineering or in science, and what more could you ask for. For me personally, it definitely showed me the power of outreach and that it can literally change somebody's life and set the course in their life. So, it really instills in me how important it is to share what we're doing and the good that can come from that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What would you say to kids these days that want to follow in those footsteps and are looking for opportunities?

Abigail Fraeman: I think the best thing to do is do what you're passionate about and do it in the way that you're passionate about doing it. For something like space exploration, there are so many ways to be involved. There's the path that I took, which is studying science and getting a career as a scientist at NASA, but there's career paths in communication and in sharing and in teaching and what you love to do and the things that you love can come together, especially in this particular field. And I think finding where that is going to get you really far.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think this program, even if it just inspired you, would've been worth all of the effort, but knowing how many other people that it inspired, how many lives it changed, it really does underscore how important these things are, and I really hope that everybody out there who wants to get into this, really does believe that they can because I know there are a lot of hurdles in the way of our dreams, but some dreams are worth chasing no matter how difficult they are.

Abigail Fraeman: Absolutely. You said it beautifully.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks for joining me, Abi and I hope that the next 20 years has even more awesome Martian exploration in store for you.

Abigail Fraeman: I hope so too. Thank you so much for having me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Courtney and Abigail's stories are beautiful examples of what happens when you empower young people to dare mighty things and pursue their dreams. We never know how it might shape the future of space exploration for generations to come. Now, let's check back in with Bruce Betts, our chief scientist for WhatsApp. Hi again, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's so touching to meet these people after all this time and see how this program changed their lives. It's no wonder that it impacted them so deeply. Can you imagine being a kid in JPL? I mean, come on,

Bruce Betts: Kind of. I was a grad student at JPL, that wasn't too much-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Grad students are kids. Really cool too to note how much involvement LEGO has had with space exploration. As an example, and this kind of blew my mind in retrospect, when you and I went to go to Florida to try to go see the Artemis 1 launch. While we were there, there was a LEGO display that we passed by but didn't actually go into, and months later, I was watching the show LEGO Masters, and I realized they had an entire space episode and the things they built and that LEGO competition were the things that were being displayed over there at the Kennedy Space Center.

Bruce Betts: Well, one thing I didn't mention is one thing LEGO did as part of our Red Rover Goes to Mars related activities. They built a full scale MER Rover out of LEGO and it displayed it for years at Kennedy Space Center.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Like actual size.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I can dig out pictures of me and others with the full size. I mean, that was back when we had smaller rovers, but still not that small. No, it was tremendous, and I forgot how many gazillion bricks were in it, but it was very impressive

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Because right behind my desk in the office, the desk that used to be Emily Lakdawalla's is a smaller rover made out of LEGOs, and when I was going through the office, Abigail pointed it out and said that they gave all the students that exact LEGO set.

Bruce Betts: Cool. Yeah. They also issued special LEGO sets, which I also forgot to mention. So they had Mars. In fact, I've got a special box, stuff they gave me of the smaller versions, and they had a big rover, but they also had the rocket that launched in a Mars Odyssey and a small Rover version. So, they got into it. People love LEGO and people love space. LEGO plus space.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm currently fighting myself because LEGO Technic just came out with a perseverance rover and ingenuity Mars helicopter, and I kind of need that.

Bruce Betts: How did I miss that?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I don't know, but we need one for the office. I'll put it in the planetary radio budget.

Bruce Betts: We need two for the society

Sarah Al-Ahmed: For the Society.

Bruce Betts: Maybe three.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It counts as a business expense. Also, I was thinking about the LEGO mini figurines that are still circling Jupiter right now aboard the Juno spacecraft.

Bruce Betts: Yep.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Those cracked me up. I mean, just thematically.

Bruce Betts: No, they're very fun. Very fun thematically. I forgot what ... they've got Galileo, and also-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That was also great about it.

Bruce Betts: Historical Jupiter related dudes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Galileo makes perfect sense. Cute little telescope, discoverer of the Galilean moons. What really cracked me was that the tiny Jupiter and then, his wife with a magnifying glass, she's staring at him because I don't know how many people know this, but a lot of the moons of Jupiter are named after people that Jupiter was involved with romantically. So, sending his wife a LEGO mini figurine to spy on him, come on. That's genius.

Bruce Betts: That's really funny. Yeah, she was always trying to figure out what was going on, and they have a whole theme with Juno. They're peering through the clouds, figuring out what Jupiter is doing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Have you seen those new pictures of Io?

Bruce Betts: Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: My goodness. Those closeup views are so spectacular.

Bruce Betts: Io is a cool, fun place. They're super cool looking. Io is super funky, super cool, and really weird.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really weird. Yeah.

Bruce Betts: No, it's nice to get some new imagery of Io, our friend Io that's always active, always spewing stuff out, so always changing. It pretty much overturns the entire surface in about 100 years.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Seriously.

Bruce Betts: I don't know. Maybe I made that up.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yikes, though.

Bruce Betts: I mean it's on kind of average, so I'm sure. Anyway, we'll keep looking at it for the next 100 years and figure it out. I'll talk to you in 100 years or 50. They've already been observing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. I'll talk to you more about this in the future. I'm hoping I can get someone from Juno and to talk about those Io images because wow, but all right, what is our random space fact this week?

Bruce Betts: Random space fact. We're going to stick with Red Rover Goes to Mars. We're going to stick with LEGO, and we're going to talk about the fact that there are six LEGO bricks on Mars made of aluminum on the two different frames. What's interesting and people seem to enjoy is that they're actually this exact layout of a LEGO brick. So you can attach LEGO bricks to those, and I have done so with our model in the office. If you pull out some LEGO bricks, the dimensions are precise enough so future astronauts take your LEGOs with you, because you'll be able to play with the bricks on Mars.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Once you dust all the Mars dust off of them, hopefully you can get them to stick together.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, Yeah. We've got magnets under the Astro Bot and so high quality magnets, so I'm sure they've just got massive amounts of magnetic dust stuck to them.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's so cool. I love the idea that we can try to clear off calibration targets and other things like that by using these magnets.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, these are not designed that way, but yes, you can. It's cool. And a lot of that dust is quite magnetic or you can attract it with a magnet.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Why is it so magnetic? Is it because it's so full of iron, or is it something about-

Bruce Betts: Yeah, there's just so much iron and I got nothing else.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So cool. All right, let's take this- All right, let's take this out.

Bruce Betts: Within a few days you accumulate ... you could see before the rovers drove away, you could see the magnets and already accumulated circles of dust. So there's a lot of stuff flying around that's magnetic and dust stormy stuff. It's just dusty there. It really needs a good cleaning.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: One of these days, I just imagine little kids on Mars playing with their magnets the way that we used to play with the magnets and iron infused cereals.

Bruce Betts: Wow. That's terrifying.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Come on, don't tell me. You've never stuck a magnet to your cereal.

Bruce Betts: No, I never have.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Try it. It'll freak you out.

Bruce Betts: Seriously?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Seriously. Even better when you get it all squishy in the water and then you can pull out the metal shavings. It's great.

Bruce Betts: You eat your cereal with water.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, for science, Bruce. For science.

Bruce Betts: For Science.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right, let's take this out.

Bruce Betts: Please end this, mercifully. Alright, everybody go out there. Look up the night sky and think about what's in your cereal because I know I am now. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with new and exciting James Webb Space Telescope results on dwarf planets Eris and Makemake. Love the show? You can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with all kinds of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space, thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email, at [email protected], or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the planetary radio space in our member community app. Thank you to the over 10,000 people that have joined us in our member community. Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our members around the world who looked up to the stars as children and never stopped. You can join us as we work to share the inspiration of space exploration with everyone at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Ray Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser, and until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth