Planetary Radio • Nov 06, 2019

Exploring Venus, Earth's Mysterious Sister Planet

On This Episode

Javier Peralta

Science team member, Akatsuki Venus orbiter

Kate Howells

Public Education Specialist for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Astrophysicist Javier Peralta takes us deep into the thick, fast-moving clouds of the world that is still called Earth’s sister by some. Venus is slow to reveal its secrets. Jason Davis helps us celebrate the 50th anniversary of Apollo 12. The Planetary Society wants to hear your space goals, accomplishments and dreams! And Bruce Betts reveals the identity of the first gourmet in space. Space headlines from The Downlink, too.

Related Links

- The Planetary Report: Venus’ Ocean of Air and Clouds

- Javier Peralta

- Apollo 12

- Share your space life goals!

- The Downlink: Planetary exploration news for busy people

- Game: The Search for Planet X

Trivia Contest

This week's prizes:

A Planetary Radio t-shirt from Chop Shop, and a 200-point iTelescope.net astronomy account.

This week's question:

What mission was the first launch of the Saturn V rocket?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, November 13th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What comet did Mariner 10 return data about in 1973?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the October 23 space trivia contest:

Who was the first person to eat in space?

Answer:

Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space, was also the first person to have a meal in space. A bad one.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Our mysterious sister, Venus, this week on planetary radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of the Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. Astrophysicist Javier Peralta has written an outstanding article in the Planetary Report about cloud shrouded Venus. We will talk with this Spaniard who has lived and worked in Japan for the last five years.

Mat Kaplan: We've reached another fiftieth anniversary. This time it's the Apollo 12 mission, and Jason Davis will remind us of its impressive accomplishments. Who had the first meal in space? We'll find out in What's Up. Bruce Betts fooled a lot of you with this installment of the space trivia contest.

Mat Kaplan: A special invitation from the Planetary Society is moments away after we sample the week's headlines from around the solar system. NASA plans to launch a water mapping rover to the moon's south pole in 2022. Viper is the volatiles investigating polar exploration rover. It will analyze ice in the moons permanently shadowed craters using a one meter long drill built by Honeybee Robotics. The Planetary Society has helped fund tests of several Honeybee Technologies over the years, including planetary deep drill and planet vac, both of which we've covered on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: The long struggle of the so called mole instrument on the in site Mars lander continues. The little self hammering probe had appeared to make progress in recent days with help from the craft's robotic arm. Well, it suddenly backed itself out of its hole. I've been told that this behavior has also been seen in the simulations under way at JPL, and that the mission team remains hopeful, but it does make me wonder about Martian gophers.

Mat Kaplan: And we now know more about another roughly spherical asteroid. Hygiea is the fourth largest in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter. With a diameter of about 430 kilometers, it was imaged by the very large telescope, yes, that's its name, in Chile. You can read these stories and more in the down link, presented by Planetary Society editorial director Jason Davis. It's at planetary.org/downlink.

Mat Kaplan: Kate Howells is another of my colleagues with a lot on her plate. Her latest dream project is one we can all participate in. She introduced me to it as I was pulling together this week's episode. Kate, I love this new opportunity, not just for our members but for everybody, right? But I got it because I'm a member of the Planetary Society. I got email from you just yesterday. As we speak, tell us about this space goals project.

Kate Howells: Yeah, so this project was actually inspired by bird watching. People who are avid bird watchers can subscribe to a life list where they keep track of all the different birds they've seen and they can get ideas for birds in their area that they might try to find. So we wanted to do a similar thing with space experiences, different things that as a space enthusiast you might want to experience or that you might have already experienced. So we want to build a way for you to get new ideas for things you can do to enrich your experience as a space enthusiast, and a way to track those things that you have done throughout your life, keep track of how much of a space fan you are.

Mat Kaplan: And this is, as I read it, not just a way to talk about things that you hope to do, but things that other people might be able to take on as well.

Kate Howells: Yeah, exactly. So the way that we're building this big catalog of space experiences is by crowd sourcing it, so we're turning to our community, our members and our supporters, our listeners, our viewers. Anybody who is tuned into the Planetary Society, anybody who is interested in space, can submit their ideas, so we're hoping to really get a lot of submissions from around the world of things that are easy to do in your back yard, like looking at the moon through binoculars, ranging all the way to things that are once in a lifetime experiences that you might have to travel to experience or pay some money to do, things like that.

Mat Kaplan: How can people get in on this?

Kate Howells: So if you go to planetary.org/spacegoals, you will be able to submit your ideas. The form lets you submit up to three, but you can do the same form over and over again and submit as many as you'd like, for those who are really keen. Over the course of the next year we're going to look through all of the submissions and finalize the ultimate catalog and release that publicly to our members and to anybody who's interested sometime next year, but it's going to be this long process to really carefully put together what we think is going to be the ultimate list of space life goals.

Mat Kaplan: You have to have expected that I would ask you for at least your top three. Have you filled one out yet?

Kate Howells: I have, yes. Some of the best experiences that I've already had include seeing Saturn's rings through a telescope. That was one of my earliest influential space experiences.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Me too.

Kate Howells: And of course, going to see LightSail launch on a Falcon Heavy rocket. I mean, I know that's a once in a lifetime experience, but going and seeing a rocket launch in person is definitely something I would recommend that every real die hard space fan try to do at some point in their life.

Mat Kaplan: I couldn't agree more.

Kate Howells: As for aspirations, I have always wanted to travel far enough north to see the Aurora Borealis. I live in Canada, so I don't have to go too, too far, but I never have seen that so that's definitely on my space life goals list.

Mat Kaplan: Can I share mine?

Kate Howells: Absolutely, please.

Mat Kaplan: These are just a few examples. Now, I would have to include that Falcon Heavy launch, and then getting the first signal back from LightSail. So yeah, one of a kind, I know. But everybody really owes themself a rocket launch, a big rocket launch, at least once in their life. I always think of the trip that I made to Chile, to the Atacama Desert, where we visited the ALMA Array.

Mat Kaplan: But much closer to home, and something that anybody and particularly you folks who are already amateur astronomers, or maybe professional astronomers, I remember when, I think I was nine or so and got my first view of Saturn through a telescope just like you, but now I love sharing it. I love going to where there are young people or adults, many of whom inevitably have never looked through a telescope, and showing them our solar system and the wonders of the cosmos for the first time. There is really nothing like it. I hope to keep doing that for a long time to come.

Kate Howells: That's a good one, yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Thanks, Kate. And thank you for this great new project. What's that URL again?

Kate Howells: Planetary.org/spacegoals.

Mat Kaplan: All right, easy enough. Check it out, and we look forward to seeing your space goals, your space dreams, your space memories in this new service by the planetary society. Thanks a lot Kate.

Kate Howells: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Kate Howells is the planetary society's communications strategy and Canadian space policy advisor. Onward to Jason Davis who has just prepared a tribute to the Apollo 12 mission. It will be announced publicly on November thirteenth, the day before the fiftieth anniversary of the launch, but ssh, don't tell anyone, but you Planetary Radio listeners can get early access at planetary.org/apollo12.

Mat Kaplan: They weren't the first to the moon, but they were the second to the moon. That's still pretty exciting, and I'm glad that we're going to... actually, that we already have this tribute to the Apollo 12 astronauts.

Jason Davis: I wonder how they feel about being the second crew. You know, I know Buzz Aldrin doesn't like being referred to as the second man to walk on the moon. I wonder how they feel about it. But yeah, I think in my book that's pretty good. Number three and four on the moon is good in my book.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely, and only 12 who made it down to the surface at all, and we should include the command module pilot. Tell us a little bit about the basics of this second, very successful, flight to the moon that got off to kind of a scary start.

Jason Davis: Let's start with that scary start. So it launched 50 years ago on November fourteenth, 1969. They launched into kind of rainy overcast skies and the Saturn V got struck by lightening twice during ascent. This had the effect of knocking out their attitude control indicator, so they were essentially flying blind, at least from their perspective. It knocked power from their fuel cells over to batteries, so they were having quite a few problems as they're riding to orbit.

Jason Davis: Luckily, the Saturn V has its own independent instrumentation that kept flying the vehicle and blasting them on to orbit even though the crew essentially didn't know what was going on. This was a pretty famous incident in which one of the flight controllers knew what was going on and recommended the crew make this obscure switch flip, and he said, "Try SCE to AUX." I've actually seen that printed on t-shirts. I don't know if you've... You know, pretty obscure space fact, but, Try SCE to AUX" was the command that restored power or it eventually helped get things back on track. They made it to orbit, checked for more damage, and ended up being okay and heading on to the moon.

Mat Kaplan: But they were moments from getting to be the first to not just test, but actually rely on, that escape system, right?

Jason Davis: It was pretty close. If they hadn't been able to restore power to those fuel cells and get their attitude control system back online, it was very possible that the folks in Houston would have triggered it on board to bring them back.

Mat Kaplan: Wow. Fairly uneventful from then on, on their way to the moon.

Jason Davis: Yeah, yeah. So they, uneventful, went to lunar orbit. Pete Conrad was the commander. Richard Gordon was the command module pilot who stayed behind, and Alan Bean was the other astronaut. It was Bean and Conrad who went down to the surface. Yeah, they landed without incident. They landed in the Ocean of Storms, that's the huge dark region you can see from earth. Oceanus Procellarum I think is maybe how it's pronounced in Latin. But yeah, they landed without-

Mat Kaplan: Easy for you to say.

Jason Davis: Yeah.

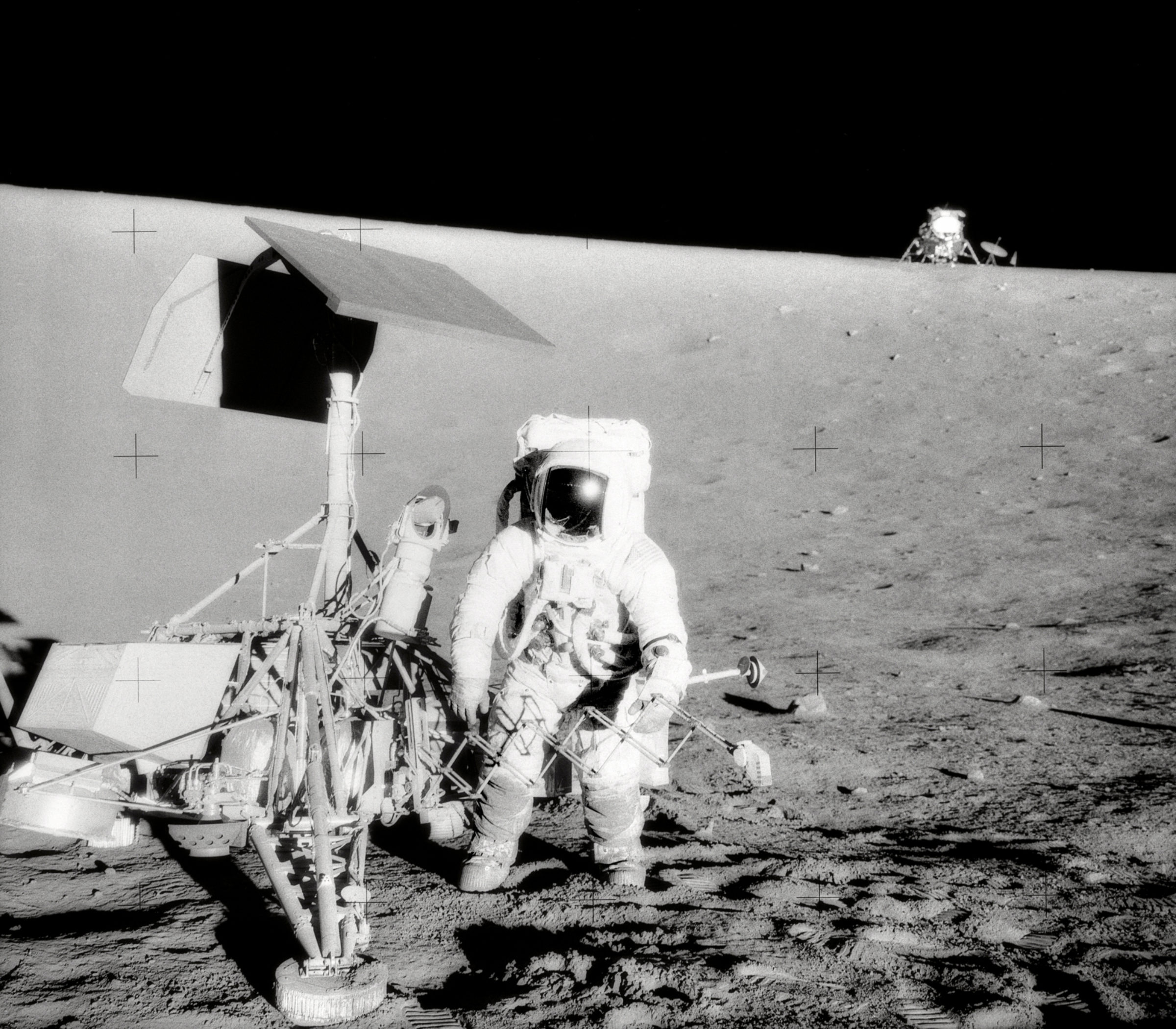

Mat Kaplan: And getting to the spot where they wanted to land, this is a great story in itself that you tell on this Apollo 12 page.

Jason Davis: Yeah, this is one of my favorite pieces of Apollo trivia that I don't think is well known, and it just so happened that when I was in grad school, I met the guy responsible for some of this. Essentially, during Apollo 11 as most of us know, Neil Armstrong had to kind of take semi manual control of the lander and dodge a bunch of boulders and a crater, because the computer was bringing them into a bad spot. They ended up landing quite a bit down range, about six kilometers away from where they'd hoped. Now, NASA knew that they needed that ability. They needed to be able to demonstrate a pinpoint landing, land right where they say they were going to, because for future Apollo crews they wanted to go to some harder to reach scientific destinations. They knew they wouldn't be able to do that unless they were able to demonstrate this pinpoint landing.

Jason Davis: But the question is, how do you know you've landed right where you intend to land. So they needed a known point on the lunar surface where they could target. Now, fortunately a couple of years before that there was this lunar scientist whose name was Ewan Whitaker. Unfortunately he's passed away now, but I had a chance to work with him when I was in grad school doing this documentary called Desert Moon. Ewan was very meticulous, and he had managed to find NASA's Surveyor 1 spacecraft after it landed. In fact, the co ordinates for Surveyor 1 were published in an academic journal, I think it was Science or something like that. And Ewan looked at that work and decided that NASA was wrong essentially.

Jason Davis: He republished his own results of where Surveyor 1, or where he thought it would be, sent them off to NASA, and NASA looked at it again and said, "You know, I think this guy's right. He's got the correct location here." So when Surveyor 3 landed, and this would have been 1967, NASA came to Ewan once again and said, "Hey, can you help us find Surveyor 3 on the surface?" So he looked at pictures from the lander, he looked at aerial photography... Well not ariel, I guess orbital photography. No air around the moon.

Jason Davis: He looked at orbital photography from the lunar orbiter spacecraft, and he was able to figure out exactly where Surveyor 3 landed, and this was a colossal task back then. You know, we didn't have all the modern digital ways of looking at maps of the moon. He's working on print, has all this stuff laid out on a table. He found exactly where Surveyor 3 was, gave NASA the coordinates, and so when it came time for Apollo 12 NASA said, "Hey, this is perfect. We know exactly where Surveyor 3 is. Let's have the Apollo 12 astronauts land next to Surveyor 3, and that will ultimately show that we can do these pinpoint landings.

Jason Davis: That's what they did. Bean and Conrad touched down, they were about 160 meters away from Surveyor 3. It was perfect, they popped out on their first EVA, and there's actual audio of them saying, "Hey look, it's Surveyor," and they were excited to see it. Yeah, it's just one of those neat little stories from the Apollo program, and the scientists who helped make that happen.

Mat Kaplan: It is a great accomplishment. Great bit of history, and what a legacy for this fellow that you actually got to interact with. And there were other advantages, because I know they went over and they took pieces off of Surveyor, right, and they got to bring them back home and see what spending two years on the moon did to a piece of machinery.

Jason Davis: Yeah, yeah. Engineers were really excited about the chance to actually bring home a piece of something that had spent that long in space. So they brought home the TV camera, and were able to look at the gears and mechanisms and see how well it had held up. And interestingly, they did find bacteria deep inside the camera. They published some initial results and said, "Hey, it looks like bacteria survived in space for two years." Then some later studies were done and said, "Well, are you really sure that this wasn't contamination once we brought it back to earth?" So the results ended up being kind of ambiguous, but it was still a really useful exercise for them to be able to visit the spacecraft.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going with life finds a way. So they wander around a little bit, they pick up some moon rocks in these two moon walks that they made, and then they come home and they're celebrated, though not quite at the level of the Apollo 11 astronauts.

Jason Davis: Yeah, I don't know if there were ticker tape parades all across the United States for them like the way they did for Apollo 11, but hey, still a pretty cool accomplishment in my book. And you know, they really paved the way for the rest of the Apollo missions to go to more ambitious places and do a lot better scientific studies of the moon's surface.

Mat Kaplan: So that's Apollo 12. Next up, things get much more exciting once again. Jason, I look forward to talking to you about Apollo 13.

Jason Davis: Sounds good. We'll do it next year.

Mat Kaplan: That's Jason Davis, the editorial director for the Planetary Society, and we will talk again on that anniversary, although very likely much sooner than that as well. We're going to take a quick break. When we return, we'll visit mysterious Venus.

Casey Dryer: I know you're a fan of space because you're listening to Planetary Radio right now, but if you want to take that extra step, to be not just a fan but an advocate, I hope you'll join me, Casey [Dryer 00:15:57], the chief advocate here at the Planetary Society, at our annual day of action this February ninth and tenth in Washington DC. That's when members from across the country come to DC and meet with members of congress face to face and advocate for space. To learn more, go to planetary.org/dayofaction.

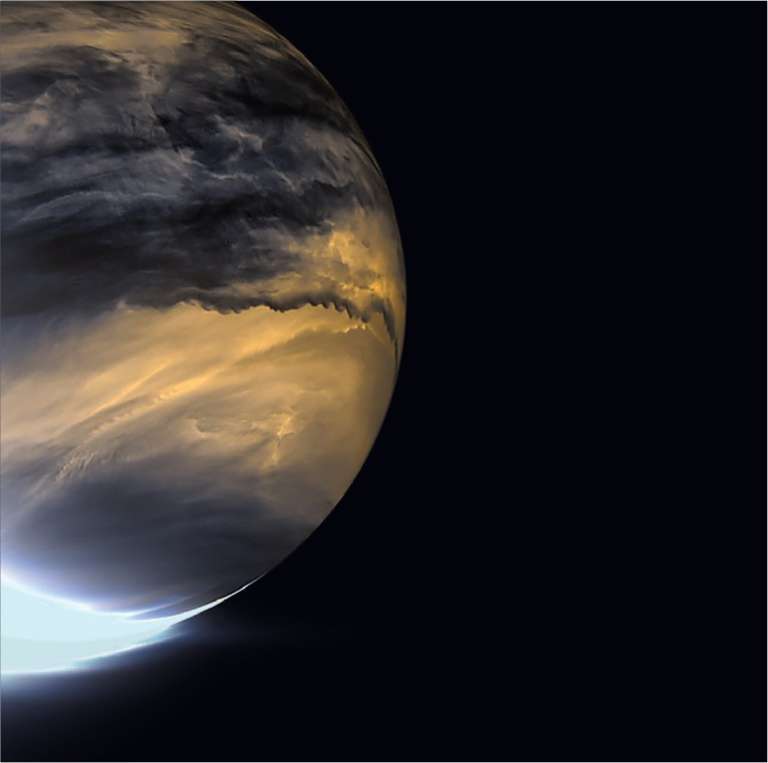

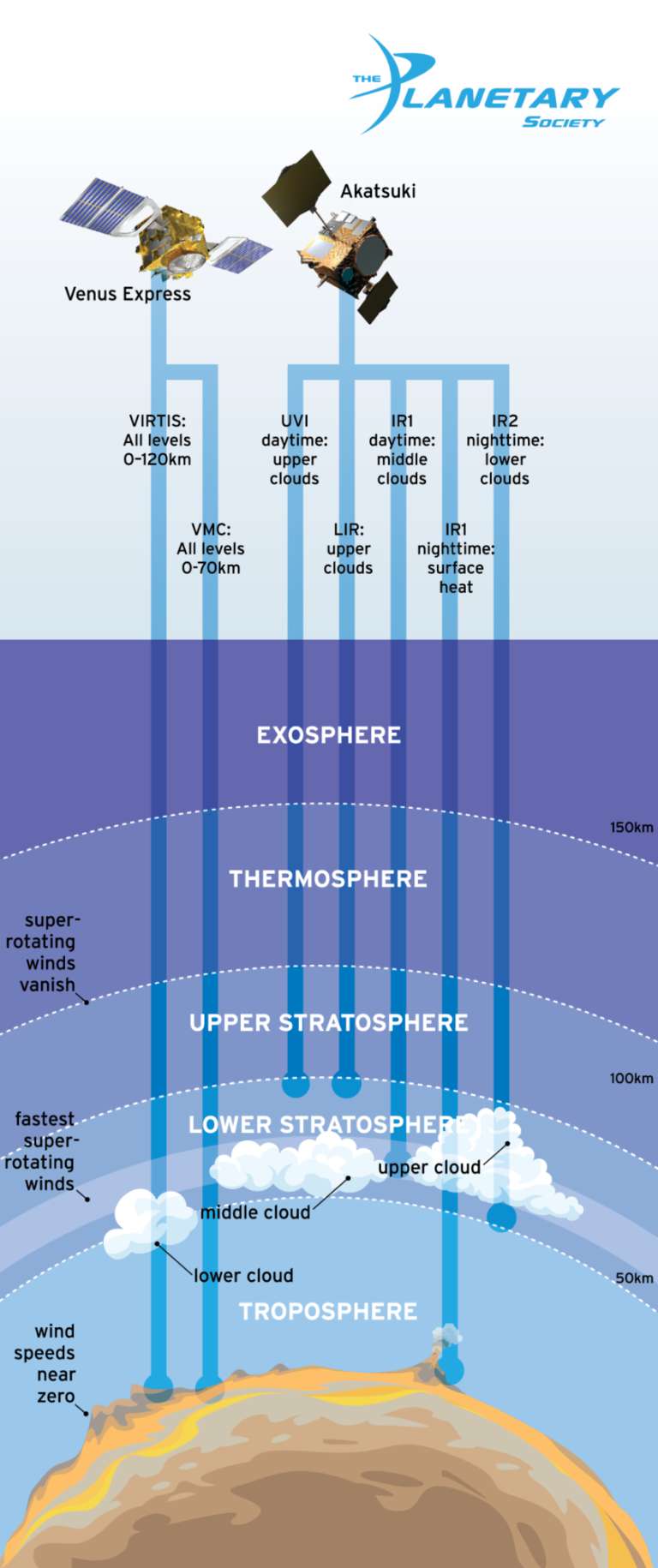

Mat Kaplan: We recently visited with Vishnu Reddy, author of that great article about planetary defense in the Planetary Report, the quarterly magazine from the Planetary Society that is edited by Emily Lakdawalla. The other major article in our September equinox edition comes from astrophysicist Javier Peralta. Spanish born Javier works for JAXA, the Japanese space agency, with most of his time dedicated to the Venus orbiting Akatsuki. He's in the forefront of our efforts to understand the complex and still mysterious Venusian atmosphere that features winds that whirl around the planet at 300 kilometers or 200 miles per hour, much, much faster than the planet rotates.

Mat Kaplan: I invited Javier to join us for a conversation about what some still call earth's sister world. Javier, thanks very much for joining me. I know that this is not the most convenient setup for you. I mean, here it's late afternoon in southern California, but for you it's still the morning in Japan. The wonders of living on opposite sides of a globe. But I'm very happy to have you on the show, and thank you for this terrific article in the Planetary Report.

Javier Peralta: Oh, thank you so much to you also. Also to Emily, because she also helped a lot for making the article. At least correcting a bit my English, because I'm Spanish.

Mat Kaplan: Right. It's wonderful that she's able to bring so many great researchers to us in the Planetary Report and elsewhere through the other work that she does on our behalf. I got to tell you, when I got my first telescope I was maybe 10 years old. I turned it on all the usual suspects, the moon, Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, but Venus, though it became a good sized disc in the eyepiece of my little telescope, was really pretty boring. A featureless, sort of yellowish white ball. For centuries, that was pretty much all anybody saw of the planet. We've made a little progress in the last 50 years or so though, haven't we?

Javier Peralta: Yeah. In fact, we didn't start to see details until the beginning of the twentieth century when we started to spot Venus in ultraviolet wavelengths. That's when we start to see details. Before that it was nearly impossible to see anything. But there were some efforts before starting to spot them in ultra violets. If I remember well, I think there was a paper... not a paper, but a book about observation of Venus published by an astronomer called [inaudible 00:18:54] in eighteenth century. It is amazing how much efforts they tried to see details and tried to measure winds or see the surface at the time.

Mat Kaplan: Well, it's not surprising. I remember as a kid, before we knew that at least at the surface Venus is not a very friendly place to life as we know it, a lot of science fiction being placed on Venus. There was a movie, a film version of Ray Bradbury's The Illustrated Man, and it depicted the surface of Venus as a jungle, a tropical jungle with huge creatures, which would be nice but not much relationship to reality there.

Javier Peralta: Yeah, I know.

Mat Kaplan: I suppose in passing we should mark the tremendous success of those Soviet Union probes led by the Venera series, which did manage to survive on the surface for substantial amounts of time. Even though you mentioned the pioneer Venus mission which had some success with an orbiter and sending probes down through the atmosphere and even to the surface, it's really, oddly enough, the Galileo mission, which was on its way to Jupiter but made a brief visit at Venus, that you point to in the article as beginning to deliver some good data, or the best data to that point, about the Venus atmosphere.

Javier Peralta: In terms of atmospheric dynamics, this is my specialty, it was the first time that we have three dimensional observations of the clouds of Venus, thanks to Galileo. Through the filters of the camera [inaudible 00:20:30] and also the [inaudible 00:20:33] called [inaudible 00:20:35] that also made observation for the [inaudible 00:20:38] of Venus. Combining these instruments we were able to observe several layers of the atmosphere, several layers of the clouds, mainly of the clouds. And it was the first time we had the chance to make tracking of this cloud features and measure the winds at different levels. It was, let's say the first three dimensional characterization of the winds of Venus.

Mat Kaplan: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Then of course [Magellan 00:21:03], which did such a great job of revealing the surface of Venus with its powerful radar. But really, if you jump forward to Venus Express, which the spacecraft that you're involved with, Akatsuki, the Japanese explorer, the only one that's active right now in orbit above Venus, it was hoped that you'd be there at the same time that Venus Express was still doing its work, right?

Javier Peralta: Yeah, that was a pity that Akatsuki didn't make it on time, because of the fall they have in the space [inaudible 00:21:37] with the thruster. Akatsuki was not able to get started and make coordinate observation with Venus [inaudible 00:21:46] have been great.

Mat Kaplan: But still, pretty heroic work by the engineers behind the Akatsuki mission, and it is certainly doing wonderful work now. Is it providing the best data about Venus's atmosphere that we've been able to gather so far?

Javier Peralta: Yes, but not as good as the one predicted. The orbit of Akatsuki was going to be different because of this incident. It was successful. The female engineer that's the scientist strategist is called [inaudible 00:22:15]. She was here considered like a hero, because she was able to recover the mission for JAXA. Right now, we have [inaudible 00:22:23] orbits, but not with [inaudible 00:22:26] resolution in the images that the instruments were designed for.

Mat Kaplan: Well, nevertheless, great science coming back. Let's talk about some of the science that you review in this Planetary Report article. You begin with a mystery, Venus very slowly rotating planet and yet it has these category nine hurricane winds. Do we have some idea of how these are being generated?

Javier Peralta: Oh, this is one of the long time mysteries about Venus. Of course, I wish I have an idea, that's what we are trying to figure out for decades, the super rotation of Venus. We are trying now to figure out one of the key points that is to know how this super rotation is fed. There was a recent work published by [inaudible 00:23:20], she is a Korean girl who was working here in Akatsuki mission too. And she made nice work combining data from Venus Express and Akatsuki to cover as much as possible for the albedo of the clouds in ultra violet wavelengths. What she discovered is that the albedo of Venus has been changing during the last 10 years.

Mat Kaplan: Just to remind our audience, the albedo, that's basically how much light Venus reflects.

Javier Peralta: Oh, yes. Yes. But in ultra violet, it reflects a huge amount of light. We a long time suspected that the energy provided by the sun through the heating of the clouds and the atmosphere was feeding energy to this super rotation. What [inaudible 00:24:08] discovered is that it seems that the albedo, the amount of light that the atmosphere is reflecting, is variable along the time, and also the strength of the super rotation fed by the solar tides. So we have for the first time pretty nice clue that seems to indicate that the periodic heating of the sun on the clouds of Venus is providing some important energy to the super rotation.

Mat Kaplan: Very interesting. I want to bring up something else that you mention, and this is an especially curious, mysterious component of the highest clouds. In fact, you call it the mysterious absorber. What do you mean by this?

Javier Peralta: Oh, I didn't call that, okay? I took the name from [inaudible 00:24:56] papers. There is no easy way to call it. Yes, as I mentioned, in the beginning of the twentieth century we started to see things on the clouds when we observed Venus in ultra violet wavelengths. There is some component of the atmosphere, especially concentrated in the cloud tops, in the radium of the upper clouds of Venus, that are located about 70 kilometers above the surface. So the cloud layer of Venus is at higher altitude compared to the earth, to the clouds of the earth.

Javier Peralta: We started to see things because precisely there is something absorbing in ultraviolet. For decades again, we have tried to discover the real nature of this absorber, and no success for the moment.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Well, the work continues, right?

Javier Peralta: Yes. Yes, of course there has been a lot of candidates to explain them. More recently, one researcher from [inaudible 00:25:53], I don't know if you know him, he suggested also that there could be a bacteria absorbing in ultra violet wavelengths, maybe floating at the radium of the clouds of Venus.

Mat Kaplan: That would be very exciting.

Javier Peralta: Oh, yes, of course. Some of my colleagues who are working with new medical models to try to simulate these absorption lines in the ultra violet, they also told me, "Oh, this complicates a bit the puzzle, because we don't know how we could try to model bacteria in our new medical models." I guess that the only way of solving this mystery is trying to send some missions able to get samples of the gases the atmosphere in some way to detect the kind of bacteria that might survive in those conditions and absorbing ultra violet. In the case of the earth, we have some species that are able to do so.

Mat Kaplan: That sounds like an excellent candidate for a future mission to Venus. We'll come back to the future. I also want to mention that you're the co discoverer of another peculiar feature, something in the clouds that appears to, actually does, remain stationary even as the winds blow, and you've got actually an image of this, one of the gorgeous images that accompanied this article.

Javier Peralta: Yeah, the stationary bowl, it was a surprise. In many instances Venus has been a surprise for many things. You can expect anything from the planet. Yeah, this image was an infrared image taken at about 10 microns. Let's say that this [inaudible 00:27:29] infrared wavelengths are the ones that some drones use to track for example the fires in forests on the earth. I mean, this wavelength is very special to track thermal heating, in the case of Venus of the clouds. So we are seeing the temperature of the upper clouds of Venus in these wavelengths. This instrument is called barometer. This image was the very first one that this barometer take of Venus, especially this was taken the exact date of the orbit [inaudible 00:28:01] in December 2015. So this was one of the main discoveries of Akatsuki that happened in the very first image of the observations.

Mat Kaplan: Well, I hope that people will take a look at this image. It is, as I said, in the September equinox 2019 edition of the Planetary Report, which is available to everybody free online. Members of the Planetary Society get the paper copy that I've got in front of me. I said it is full of beautiful images and some terrific graphics. We're not going to be able to cover everything here, but there is one other series of four images that we just have to talk about, and it's not that they're just awe inspiring. I actually find them rather creepy, and I bet you can guess which ones I'm talking about. It's the maelstrom at the south pole of Venus, and this is one very strange looking feature.

Javier Peralta: Polar vortex?

Mat Kaplan: Yes.

Javier Peralta: Okay, yeah.

Mat Kaplan: And these are from the Venus Express's [inaudible 00:29:04] instrument. It's at the south pole.

Javier Peralta: Honestly, this phenomena was observed for the first time on the northern hemisphere by pioneer Venus.

Mat Kaplan: Do we understand the dynamics of a vortex like this? We seem to be finding such interesting things at the poles of a number of planets. Jupiter, Saturn, and now Venus.

Javier Peralta: Oh, I must admit, not yet. No, I mean, this vortex is subject to very fast changes in [inaudible 00:29:35]. The images that appear here are an example of that. can have a circular shape, sometimes like a double, sometimes a triple. Can change in just two days about, in 48 hours. We have many sequences of this polar vortex taken with [inaudible 00:29:56] Venus Express. Unfortunately this instrument worked for only the first two years of the mission, but in those two years we managed to take many, many sequences of the motions of this structure. It is funny, because one of the first works we published about the dynamics of this polar vortex was published by my boss in Portugal, David [inaudible 00:30:20], in Science. What he discovered is that this polar vortex seems to reproduce the motion of a merry go round. So it was moving about itself at the same time moving around the geographical pole.

Mat Kaplan: It is fascinating.

Javier Peralta: Yeah, yeah, yes, but afterwards, if I remember well, a couple of years later another colleague from Spain,[inaudible 00:30:43], she made a more extensive [inaudible 00:30:45] with the dynamics covering different dates than David [inaudible 00:30:48], and she discovered something completely different. It seems that the motion of the vortex is rather [inaudible 00:30:56], so the case of the merry go round seems to be a special case or maybe some kind of stage of the dynamics, but others is completely [inaudible 00:31:06]. We can see also this polar vortex in the lower clouds, in the cloud tops and even a bit above the cloud tops. The position of the polar vortex in the lower clouds was not exactly the same as the cloud tops. So it seems that in the three dimensional structure since 20K that the polar vortex may be something closer to a helicopter.

Mat Kaplan: Say that again, it's closer to what?

Javier Peralta: Oh, yes, I mean that exactly the position of the polar vortex at the level of the cloud tops, I mean 70 kilometers above the surface, okay? When you observe at the same moment the position of the vortex at the lower altitude, about 50 kilometers, the position of the vortex at these two levels is not the same. There is some differences in the location. It seems that the polar vortex might be bended in altitude.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely fascinating. I mean, we see images sometimes of tornadoes here on earth where the neck of the tornado or where it is closest to the ground can be quite far from the top of the tornado, and it sounds a little bit like what you're describing.

Javier Peralta: We don't know how that is. Like kind of a coordination in the motions of the polar vortex in the north and the south. And this is something we are trying to confirm with barometer observation from Akatsuki, so it is an ongoing work. We have already some indication from ground base observations that the motion of the polar vortex of the north pole and the south pole of Venus seems to be somewhat connected in some way because of the general dynamics, and they have same quality maybe motions between the north and the south. Of course, we need to confirm this, but this is what observation seems to indicate.

Mat Kaplan: You have provided, in this conversation and especially in the article, ample evidence that Venus is a very dynamic place and that we still have a lot to learn. Other than sending something to look for that possible bacteria in the atmosphere, what would you like to see happen next? What missions do you think we should be sending to Venus in the coming years?

Javier Peralta: First, we need a mission to be approved, and that has been really hard. The Indian space agency is preparing a mission to be launched. I think that's in four or five years they want to do so. I hope they are successful, of course. But to my opinion, of course I will be really delighted to see a mission able to penetrate through the clouds and try to observe all the deep atmosphere of Venus that is completely unknown to us. I mean that since the 80s, we don't have barely information about what is happening below the clouds, and that's information in many senses critical to understand the atmospheric dynamics of Venus and also the thermal structure.

Javier Peralta: Many people are obsessed to try to promote missions able to penetrate and go to the surface, so yes, exploring the surface that is like a black box to us will be really great. But of course at the same time, we are also trying to perform a more detailed global characterization of Venus, and the problem we have right now has to be, for example, the technique of radio [inaudible 00:34:26] that consists in emitting radio signals through the atmosphere of Venus, so the spacecraft senses radio signal. This radio signal is bended by the atmosphere and then directed to the earth where we get the signal.

Javier Peralta: Because of the angle that the signal is bended and also the signal is retarded, we can get information about the temperature of Venus, the pressure of the atmosphere with high precision.

Mat Kaplan: How about a balloon, something that has been talked about for many years?

Javier Peralta: Oh, I will say how about several balloons.

Mat Kaplan: Maybe to go with those seven orbiters.

Javier Peralta: Oh, that will be amazing. To have several balloons like the big mission in the 80s, [inaudible 00:35:05] our parameters. Yeah, that will be really great, and I don't think it's so expensive for a mission. I know that there has been some proposals also about balloons, but I confess that right now people are more obsessed in trying to investigate the deeper atmosphere below the clouds, and also the surface. There could be some chances in the next future, but according to the air force of the people deciding new space missions, I will say that it will take yet a bit of time to see balloons again on Venus.

Mat Kaplan: Okay.

Javier Peralta: So, yes, we can have balloons, and the merry go round for a vortex. It will be really funny.

Mat Kaplan: That would be quite a ride. I've got just one other question for you if you don't mind my asking.

Javier Peralta: Of course.

Mat Kaplan: How does a Spaniard end up living in Japan and contributing to space missions underway there by the Japanese space agency, JAXA?

Javier Peralta: I have to say that this is really different compared to my previous experience in the European space agency. As you know, the European space agency is a contribution from many countries. Here, JAXA is a national agency. Especially where I work you don't see so many foreigners, so of course the majority of the people working here are Japanese people. In that sense, I confess that it's kind of hard not only... Of course, for me to understand Japanese, for them also to speak English.

Javier Peralta: And yet, they are trying to go ahead with an internationalization plan for the agency, because right now at the moment a lot of the work that is done here, unless we are talking about combined mission form different countries, is done in Japanese. I lived in another [inaudible 00:37:08]. Not so many people speak English here. It is quite an experience for a foreigner. I recommend at least to learn a bit, to have some solid base of Japanese to start with, and then start to work. People here work very hard. It is very difficult to find time to study Japanese, that is not the easiest language of the world, of course.

Mat Kaplan: And besides, you're busy doing science. It does seem to put you in a good position as international efforts go forward, to undertake planetary science missions, and especially perhaps Venus missions. So congratulations on taking on this challenge. Thank you for that.

Javier Peralta: Oh, thank you so much.

Mat Kaplan: And I will just say once again that anybody can take a look at your excellent article in the Planetary Report. Venus's Ocean of Air and Clouds, Deep Dynamic Currents Revealed by Venus Express and Akatsuki, by our guest Javier Peralta, who is speaking to us from Japan where he has been doing this work for five years. Javier, thank you so much for being part of Planetary Radio as well.

Javier Peralta: Oh, thank you so much for giving me the chance to explain it a bit further.

Mat Kaplan: Astrophysicist Javier Peralta studies planetary atmospheres and, as you've heard, especially the atmosphere of Venus. He's on the mission team for the Japanese space agency's Akatsuki, currently orbiting that clouded mystery every 10 earth days. He was awarded an international top young fellowship as part of his participation. Born in Spain, he's been learning Japanese now, learning it in situ for five years. I'll be right back with Bruce and this weeks What's Up.

Jason Davis: Hi, I'm Jason Davis, editorial director for the Planetary Society. Did you know there are more than 20 planetary science missions exploring our solar system? That means a lot of news happens in any given week. Here's how to keep up with it all. The down link is our new roundup of planetary exploration headlines. It connects you to the details when you want to dive deeper. From Mercury to inter cellar space, we'll catch you up on what you might have missed. That's the down link, every Friday at planetary.org.

Mat Kaplan: Time for What's Up on Planetary Radio. Bruce Betts is here. He's the chief scientist of the Planetary Society, back to entertain and inform us with that night sky and all kinds of other good stuff.

Bruce Betts: If you're getting this before November eleventh, do not miss the rare transit of Mercury across the sun as Mercury passes between us and the sun on November eleventh, and that will be starting at 12:35 UTC and then ending at 18:04 UTC. In Pacific time that's 4:35 in the morning, so we won't see it rise here on the west coast of North America, but we will see the last few hours of Mercury in front of the sun, because it ends at 10:04 AM Pacific time. There won't be another one until 2032. You will, however, need a telescope with proper safety filters, or there are all sorts of sites on the web covering it, including spacecraft in space observing it and observatories on earth. So just to search for that. And finally, and maybe I should have started with, this will be visible from South America, Africa, most of North America, and Europe, so have fun with that.

Bruce Betts: If you miss that, or even if you don't, check out the evening sky, it's starting to become a planet party. Venus is joining Jupiter and Saturn, which have been hanging out in the south west in the early evening for a long time. Venus is now super bright as always, down below bright Jupiter far to its lower right. The trick is you'll need a clear view to the horizon, but don't worry if you don't see it. We will have it visiting for several months now.

Mat Kaplan: If you don't mind, I will tease something even though it's not an absolutely sure thing. You remember, you know Yay [Pasacoff 00:41:17] right?

Bruce Betts: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: He was not just an eclipse chaser, but not surprising a transit chaser, micro eclipse chaser. I got to trademark that. He is going to be at the Big Bear solar observatory and we're going to try and connect as the big solar telescope there, as the sun with Mercury already transiting comes into view. And if this happens, we'll have that phone call on next week's show, which will be two days after the transit, so wish me luck. Wish us luck.

Bruce Betts: Good luck. You know, I'll be looking at it through little tiny telescopes. Don't you care about me? That's okay, Jay knows more about this stuff than I do and that telescope's cooler, so go ahead.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, it's big, and they're good people up there anyway, so...

Bruce Betts: Yeah. All right, we move on to this week in space history. Carl Sagan was born this week in space history, in 1934. He would have been 85. Carl Sagan, founder of the Planetary Society, and he did other stuff I hear too.

Bruce Betts: Okay, we move on to random space fact.

Mat Kaplan: That belonged on some British television. You didn't really have the accent, but it was so sophisticated.

Bruce Betts: It does raise the question whether one can sound sophisticated without a British accent. I'm not sure.

Mat Kaplan: It's much harder.

Bruce Betts: On to the fact. Although Apollo 6 experienced a couple of engine failures and Apollo 13 had an engine shutdown during launch, both of them had the on board computers compensate using the other engines to get into a earth orbit. Side note, none of the 13 Saturn 5 launches resulted in pay load or human loss or casualty. Pretty spiffy, I know you're a big Saturn 5 fan. It's a big rocket.

Mat Kaplan: I am, and this is so appropriate, because we just heard not long ago from Jason Davis about how Apollo 12 that we're about to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of was hit by lightening.

Bruce Betts: Twice.

Mat Kaplan: Yes, and that one was saved as well by a smart human on the ground who said, "Throw this switch."

Bruce Betts: Okay, we move on to the trivia contest, and I asked you who was the first person to eat in space. And I hear we had some differing opinions. How'd we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: This is so interesting. We had a somewhat larger than normal response, maybe because people thought this would be so easy or that it was so easy to look up. I hate to say it folks, but more than half of you got it wrong.

Bruce Betts: Wrong.

Mat Kaplan: Yes, John Glenn was the first American to eat in space, but it was, dah-dah-dah-dah, Yuri Gagarin, right?

Bruce Betts: Indeed. He had two tubes of pureed meat, tube of chocolate sauce to wash it down with.

Mat Kaplan: And this came up recently on the show as well, when you asked what he wanted to eat. A couple of people remembered that question. Here's our winner, Zachary [Mupin 00:44:25]. Zachary, who is from Iowa, back in Iowa now I think, but he spent his summer as an intern at JPL working on the Europa Clipper mission.

Bruce Betts: Cool.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, brought people over to the Planetary Society, got a nice tour as I understand. He said, "I was very surprised to learn that it was Yuri Gagarin." He says he loves listening from the heart of Iowa. Congratulations Zachary.

Bruce Betts: I think the confusion is because John Glenn brought a waiter, so it seems...

Mat Kaplan: What a class act. Anyway, Zachary is going to get that new board game and the accompanying app called, "The Search for Planet X," which very successfully completed its kick start campaign. Looks pretty cool. I know you played with the prototype that was at the office. And we'll put the link back up on the show page, you can get there from planetary.org/radio. And he'll also get a 200 point itelescope.net astronomy account. But wait, there's more.

Bruce Betts: Oh, really? No way.

Mat Kaplan: John [inaudible 00:45:27], "This couldn't happen today because the tubes of paste were 5.6 ounces each, and we all know the TSA doesn't allow anything more than 4 ounces to get through screening. Then he says, "While I'm good with the chocolate paste, I sure hope the Planetary Society doesn't serve any meat paste in a tube at its next big event."

Bruce Betts: Really?

Mat Kaplan: We'll alert the chef to change those plans, okay? Mel Powell, "So Yuri finished his meal, and then left a vicious anonymous online review later about the quality of the dining experience under the pseudonym Only Guy Been To Space."

Mat Kaplan: A whole bunch of people talked about Gherman Titov, who was the next person [crosstalk 00:46:16]

Bruce Betts: First to hurl in space.

Mat Kaplan: Exactly. That's because you talked about this recently.

Bruce Betts: Yes. His claim to infamy.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Stephanie Gordon, she said John Glenn and she knew that he had apple sauce, but she said, "Just hearing about this brings to mind children's snacks. Can you imagine the mess a toddler would make in zero gravity?"

Bruce Betts: Oh yeah, that would not be good. Well, my kids are pretty neat, but on average, yeah, that would be bad.

Mat Kaplan: Oh not mine. Not mine. Sorry girls. Manuel [Bacere 00:46:48], he's in Portland, Oregon. Yes, he thought it was John Glenn. Wrong there, but he may be right about this. "First non human," he says, "I suspect, was Fred Flintstone's friend the Great Gazoo." That was the stone age, right? Yeah?

Bruce Betts: I guess that would have to be before the others in some universe.

Mat Kaplan: In the Hanna Barbera universe. Finally, this from Laura Weller in the UK, and I helped it out a little bit Laura, I hope you don't mind. "In space flew a man called John Glenn, he ate apple sauce and flew back again, space hinders your taste, so next time when faced with space snacks perhaps add cayenne." Very clever. Thank you Laura. Well, the poet laureate has the week off. That's it. We're really done now. That was fun stuff.

Bruce Betts: All right. Move on to something that I think should be straightforward. What mission was the first launch of the Saturn 5 rocket? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: You have until the thirteenth, two days after the transit, Wednesday, the thirteenth of November, at 8:00 AM Pacific time to get us this answer and win yourself a Planetary Radio t-shirt. That comes from the Chop Shop store of course, chopshopstore.com. See our whole store there, the whole Planetary Society store. And a 200 point itelescope.net account. I'm sure they're going to have telescopes looking at the transit, so you don't have to buy a thing because you operate the telescopes remotely. 200 point account on iTelescope, that worldwide network of remotely operated telescopes. And that's enough about that. We're done.

Bruce Betts: I'll add one little tidbit, which is Thursday before the transit I will have a blog online if you're looking for more information, go to planetary.org about the transit.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Bruce Betts: All right everybody, go out there, look up at the night sky and think about what food you'd like in a tube like a toothpaste tube. How do you say that if you don't call it a toothpaste tube? I don't know. Thank you, and good night.

Mat Kaplan: Bacon. Got to be bacon paste, right? That's Bruce Betts. Thank you also for that update about your upcoming blog at planetary.org about the transit. There's so much more that he keeps on giving us as the chief scientist of the Planetary Society who joins us every week here for What's Up.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its members who want to peek want to peek below those Venusian clouds. Learn how to become a member of the society at planetary.org/membership. Mark Hilverda is our associate producer, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. I'm Mat Kaplan. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth