Planetary Radio • Dec 03, 2025

ESCAPADE begins its journey to Mars

On This Episode

Ari Koeppel

Policy and Advocacy Fellow for The Planetary Society

Robert Lillis

Principal Investigator for ESCAPADE Mars mission, Research Scientist and Associate Director of the Planetary Group at the UC Berkeley Space Sciences Lab

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

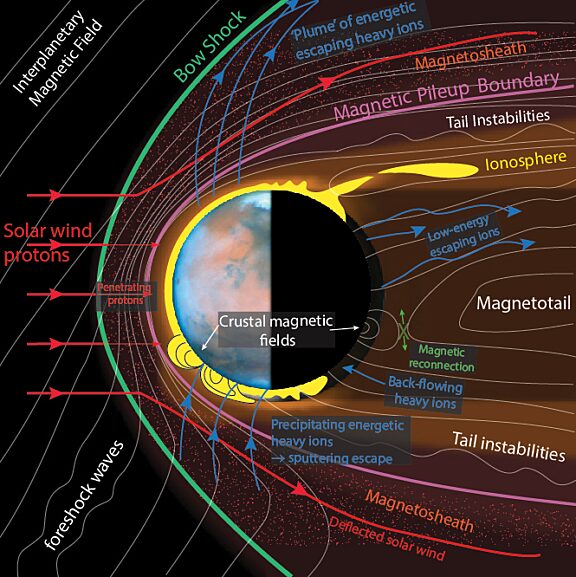

NASA’s twin ESCAPADE spacecraft have finally launched on their journey to Mars. Designed to study how the solar wind interacts with Mars’ patchy magnetic fields and drives the loss of its atmosphere, ESCAPADE is NASA’s first dual-spacecraft mission to the Red Planet and a major milestone for the SIMPLEx program’s small, low-cost planetary explorers. The mission began its voyage aboard Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket after several weather and space weather delays, marking the vehicle’s first science launch.

We begin with Ari Koeppel, AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellow and Space Policy Intern at The Planetary Society, who was at Cape Canaveral for the prelaunch activities. Ari shares what it was like to navigate repeated scrubs and even a powerful solar storm, along with the emotional experience of watching a spacecraft carrying an instrument he helped build begin its voyage to Mars.

Next, we are joined by Dr. Rob Lillis, ESCAPADE’s Principal Investigator and Associate Director for Planetary Science at UC Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory. Rob explains how ESCAPADE aims to unravel Mars’ complex space environment using two coordinated orbiters, why its measurements are key to understanding atmospheric escape, and how its innovative trajectory made the mission possible after the loss of its original rideshare opportunity.

Finally, Dr. Bruce Betts, Chief Scientist of The Planetary Society, returns for What’s Up to talk about why Mars produces aurora even without a global magnetic dynamo.

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: NASA's twin ESCAPADE spacecraft have finally launched this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. After weather delays, a government shut down and even a powerful solar storm, NASA's ESCAPADE mission finally began its journey to Mars on November 13th, 2025. The twin spacecraft will study how the solar wind interacts with the Martian atmosphere and its patchy magnetic fields. That's key to understanding how Mars lost so much of its atmosphere over time. Today, we're celebrating this achievement with two conversations. First, we're joined by Ari Koeppel, AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow and space policy intern at The Planetary Society. He was at Cape Canaveral for the pre-launch events. He'll share what it was like to navigate multiple scrubs in a solar storm delay to watch the second ever Blue Origin New Glenn rocket launch and fill that deeply personal experience of watching a spacecraft carrying an instrument he worked on begin its journey to another world. Then we'll learn more from Rob Lillis, ESCAPADE principal investigator and associate director for planetary science at UC Berkeley's Space Science Laboratory. He'll walk us through the mission science goals, its unusual trajectory, and how two small spacecraft working together can map the dynamic interactions between Mars's very strange magnetic fields and the solar wind. And later in What's Up, Bruce Betts, the chief scientist at The Planetary Society, joins me to talk about why Mars still produces auroras, even though it doesn't have a global magnetic dynamo. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stand formed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. ESCAPADE is short for Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers. It's a pair of identical spacecraft built to study how the solar wind interacts with Mars's patchy magnetic fields and how that process drives the loss of its atmosphere over time. It's a small mission with a really ambitious goal, mapping Mars' space environment from two vantage points at the same time and coordinating with other spacecraft to learn even more. To talk about the events leading up to the launch, I'm joined by Dr. Ari Koeppel, a AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow and space policy intern here at The Planetary Society. Hey, Ari, welcome back to DC.

Ari Koeppel: Hi, Sarah. Great to be back on the ground here in DC and also to be back on the show with you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you got to be onsite for all the meetings and the events leading up to this ESCAPADE launch. I understand you didn't actually get to see it in person because of all the delays, but what were some of the events that you got to attend and what was the atmosphere with the people there?

Ari Koeppel: Yeah, so just a bit of background. I actually have been involved in this mission for probably going on four or five years now. I originally got involved in this mission as a graduate student working on the development of an instrument called the VISIONS Camera, which is really the only imaging tool aboard the ESCAPADE mission. My involvement with the project has largely been through my involvement with the VISIONS camera team. And so leading up to this event, I had been working with the science team and the VISIONS camera team, making sure that everything was in order. There was a lot of anxiety. Is our camera mounted on the correct spot on the spacecraft? Is our camera going to turn on when the spacecraft turns on? And then also, are the conditions for launch going to be suitable? We really didn't know whether the launch was actually going to happen in this short time window, which is basically early November. We didn't know until about two weeks ago, and that's when they did the static fire test on the New Glenn rocket. What that test does is it basically tells us the rocket is firing normally and it's ready to go, and we're going to aim for that nominal launch window. The original time window was the afternoon of November 9th. So that's when everyone basically booked their tickets, booked their travel, and the official viewing party was set at actually this bar and grill called Fishlips Bar and Grill. It's kind of a funny name. And the reason they picked that is it's a big venue where they could throw this viewing party in a festive environment that overlooks the launch site just across the inlet that separates Cape Canaveral town from Kennedy Space Center, which is on the other side of the inlet. And it's actually, it turns out a better viewing spot than the Blue Origin Factory, which has this whole viewing platform, but is obscured by a forest in between. And so because there's no forest in between Fishlips and the launchpad 36, we had this clear view of the launchpad. The atmosphere was festive, but at the same time, there were these scattered storms moving through the area. And so everyone's looking to the horizon wondering, "All right, is that storm going to move through the path of the launch site?" There's all these overhead screens typically used for watching sports games, but in this case, they were streaming various streams relevant to the space launch, Blue Origins official launch, Spaceflight Now's official launch viewing, and then also weather radars. So everyone's watching the weather radar. "All right, is this storm track going to move across the launch site?" Seemed like we were going to actually make it happen on that first go around. And then a cruise ship moved in front of the launch path and blocked out that opportunity. And then there were some other technical difficulties it sounds like at the launchpad. They had some issues with the mechanisms that hold down the rocket. And the result is that that first launch was scrubbed. They set another launch date for the 11th. And early in the morning of the 11th, that launch was called off because it turns out, ironically, a probe going out to measure high energy particles from the sun is delayed by the largest solar storm of 2025, which happened to hit the night of the 10th and through the 11th. So then the launch was delayed to the 13th. I had to fly back on the 12th, so I did not actually get to see the launch. But in the meantime, between arriving on the 7th and leaving on the 12th, I got to go to the official launch viewing at Fishlips, go to a bunch of happy hours with the mission team, commiserate over our anxieties over whether this thing was going to launch and whether the spacecraft was actually going to power up and talk about the future of science at Mars.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I tell you, if all of the local restaurants and bars showed space launches on all the screens like they do with sports teams, I'd probably get out of the house more. That sounds like so much fun. But also definitely anxiety producing. There's so many firsts about this mission. So far, every mission launching within the SIMPLEx program hasn't gone according to plan. It's the first time we have a science mission launching on a Blue Origin New Glenn rocket. Also, the timing with the launch. We'll get into that a little later in the episode, but I've seen the New Glenn rocket in pieces on the Blue Origin factory floor. I went to go see it during the first attempt at the Artemis I launch, which I also didn't get to see because I had to leave, but I can't imagine how impressive this thing must be in person. What was it like actually getting to see that thing?

Ari Koeppel: That rocket was massive. I think it's an amazing piece of engineering. Not only is it a multi-stage rocket, but it also has this ability to land itself on this landing pad that they call Jacqueline, which is a floating barge at sea. And it does that through a series of articulated engines that move back and forth and can move it not only up and down, but sideways. And then it has these kind of landing legs that come out as it's approaching its final landing target. It's funny, the Blue Origin team was so ecstatic that this project actually worked. They had made one attempt before to land the first stage of the rocket and it ultimately wasn't successful. And so this was actually the first success for them to be able to land the New Glenn or NG2, the second edition of this rocket.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it's always so anxiety producing in the beginning. And then ultimately you hit that point where you're just absolutely ecstatic that everything seems to be going to plan. And thankfully, I'm really glad not just for the mission, but also for you as someone who got to work on one of the instruments that this actually went according to plan because I know the heartbreak of so many people that work with us at The Planetary Society that have been working on some of these missions that didn't go according to plan. But can you tell us a little bit more about the imaging systems on board that you've been working on?

Ari Koeppel: Yeah, so this is a really unique collaboration between NASA and Northern Arizona University. This is an instrument called the VISIONS Camera, and it is unique because it's funded under an entirely new model for NASA. It's actually basically a ride-along for this mission. It was funded entirely by the university's funds, which is an interesting concept for the future of NASA missions. There's been a lot of talk about reducing cost emissions, whether universities can uptake it. I tend to think this is actually a pretty unique circumstance and not necessarily a long-term model for this type of development, but it is one that turned out pretty well in this situation. The university basically was given this opportunity to develop a component of the mission that wouldn't have otherwise been on the mission, but one that was really important for making sure that this mission has some public visibility beyond just the initial launch. And what I mean by that is that this is primarily a heliophysics mission, a mission with a bunch of instruments that measure things that are pretty hard for the general public to conceptualize like high energy particles, the movement of ions from the in and out of the atmosphere of Mars, how the magnetosphere of Mars interacts with solar wind or particles coming from the sun. These are all things that answer important science questions about Mars. They tell us how Mars might have lost its atmosphere through time, which is something that is really important for understanding habitability on Mars. We think some four to three and a half billion years ago, Mars likely had a surface environment that was pretty similar to earths. Sometime around 3.5 billion years ago, its atmosphere got wiped away by solar wind because its magnetosphere declined. We still don't know exactly why that occurred or how that actually took form. And so the primary goals of the ESCAPADE mission are to answer those questions, but there's not a lot of information you can show in press releases from a mission that's measuring things like that. One thing you can show in press releases are pictures. And so I was part of this team as a grad student developing these cameras through a student organized program at Northern Arizona University where we had a set of student-led teams as well as professional advisors from professors and research scientists to build these space-ready cameras that could ride along the two ESCAPADE probes, Blue and Gold, and not only take pretty pictures, perhaps even take pictures of one another because it's two probes, we can maybe look at one another, but also do a little bit of science. And my role on the team was actually as the science team lead, meaning I was coming up with the actual science questions that we might be able to answer with some cameras. And in particular, because this is a heliophysics mission measuring high energy particles and also relevant to some recent events here on Earth, we're interested in seeing if we can try to track the auroras on Mars. And so in tandem with these high-tech, high-energy particle instruments that are measuring solar wind and its interaction with Mars's magnetic field, we now have these cameras that are mounted on the two ESCAPADE probes that can potentially actually see the green glow of the Aurora. And so we can pair those things in tandem. And so whenever that phenomena occurs, we'll now have the opportunity to put out a press release that says, not only did we detect these with the three major instrument packages that are measuring solar wind and high energy particles, but we also took a picture that you can see with your two plain eyes. And we're really excited about the opportunity to do that and we're excited that we are able to institute this unique partnership as a ride along with the mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm sure it means so much to you and so many of the other grad students and other students in general that have been able to work on this kind of thing. If I had that opportunity at university, I would've lost my mind. It would've felt so great to be a part of that. And I say it time and again, but putting cameras on missions for communications purposes, it's so, so important. And I know in my heart, one of these days, we're going to get back one of those images from Mars with the auroras. I would love to see the look on your face the first time you get to see those pictures.

Ari Koeppel: Yes, I would be even more ecstatic than the actual launch would be getting usable data back that's showing us the wonders of Mars and the broader universe.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I'm sorry you didn't get to see that launch in person, but it sounds like you had a wonderful adventure and many adventures to come when this thing finally gets to Mars or when it slingshots around the earth to try to get out to Mars. There's still several steps along the way. But thank you so much for sharing part of the story with us and for going on this awesome adventure and reporting back.

Ari Koeppel: Yeah, thank you, Sarah. It's been fun to follow along with this mission after my involvement in engineering the instrument has come to an end and hopefully we'll get some images back soon that we can share with the broader world.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Fingers crossed.

Ari Koeppel: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks, Ari.

Ari Koeppel: All right. Thanks, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Good news for Ari and the VISIONS Camera team. On November 21st, the camera that's aboard ESCAPADE gold captured its first light view, which was looking across the spacecraft solar panels. I'll put a link to that image on the webpage for this episode if you want to look at it. Now, if you've been listening to Planetary Radio for a while, you might remember that Dr. Rob Lillis has been on here before. Back in 2021, he joined my predecessor, Mat Kaplan for an episode called An ESCAPADE to Mars on the Cheap. That was back when this mission was still mostly a bold idea, sent two orbiters to Mars for a fraction of the price of a traditional flagship mission. ESCAPADE is part of NASA's SIMPLEx program, which stands for Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration. It was created to test whether small, relatively low cost spacecraft could do serious planetary science work by accepting more risk and leaning heavily on commercial partners. There have been other SIMPLEx missions that have launched, but all of them have run into major problems after reaching space. ESCAPADE is actually the first to make it cleanly through launch and early operations and to begin a healthy cruise phase. The mission is led by the Space Science Laboratory at UC Berkeley, which is where Rob is based. They worked with Rocket Lab on the twin ESCAPADE spacecraft called Blue and Gold, named for the UC Berkeley colors, and it was built on the company's photon bus. A set of partners supplied a bunch of the instruments, which you'll hear more about in a little bit. At some point, ESCAPADE lost its original rideshare opportunity, so the mission team had to completely rethink how to get it to Mars. After launch, the spacecraft is going to detour to the Earth-Sun Lagrange .2 for about a year. Then, once Earth and Mars align better, the spacecraft is going to loop back toward Earth and then use Earth's gravity to slingshot towards Mars using an Oberth maneuver. It'll take a little bit to get there, but once Blue and Gold actually arrive at Mars, they'll start out in similar elongated orbits before they finally drift apart, giving scientists two vantage points on the Martian magnetosphere and letting them watch how the solar wind reshapes the environment on timescales of just a few minutes. To explain how all of this works and how ESCAPADE can finally tell us more about how Mars lost so much of its atmosphere, I'm joined by Dr. Rob Lillis, ESCAPADE principal investigator and associate director for planetary science at UC Berkeley's Space Science Laboratory. Hi, Rob. Welcome back to Planetary Radio.

Rob Lillis: Hi, Sarah. Good to see you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's been four years since you spoke with my predecessor, Mat, about this mission. And in that time, your team has not only put together this mission, but a lot has changed in the moments in the interim. But Blue and Gold are now officially launched. What was it like to be there with the rest of your team seeing this thing blast off in Florida?

Rob Lillis: It was exhilarating. It was anxious, as is true for any launch, but it was great to be with team members, family members, and a lot of people at Blue Origin who were also anxiously watching their second launch as well. And so it was really a great atmosphere at Blue Origins Rocket Park headquarters in Merritt Island, Florida for that. So we had a clear view of the rocket as it was going up and we were near the launch control room. So there was great celebration when the launch was successful, when the booster was recovered successfully when the spacecraft separated. It was a very jubilant atmosphere, and it was followed by a champagne toast between Nikki Fox, Jeff Bezos, and Dave Limp to celebrate the accomplishment.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I was watching it from home, watching the live stream, and you could just feel the excitement of everybody there when this thing went up. There was so many new moments to this, not just this mission launching, but the success of the landing of that booster, along with the fact that this was the first real kind of science test, science mission going up on the New Glenn rocket. And I had the privilege of being at that rocket factory, the Blue Origin Rocket Factory. When I went to go see the Artemis I launch, I got to be there with Bruce Betts to see that rocket and pieces on the floor. I can't even imagine how large that thing is in person.

Rob Lillis: The New Glenn, yes, we were also very privileged to get a launchpad tour on November 8th, the day before the first launch attempt. So we got to see the rocket all stacked up from just maybe 150 yards away, and we got to take lots of pictures with it. And it is very impressive up close. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But you did have a few moments, weather scrubs and also space weather delays during this time.

Rob Lillis: We sure did.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. What was that like just emotion-wise, not knowing which day it was going to go up and having to return there repeatedly?

Rob Lillis: Yeah. Yeah. Well, actually, I was there even a couple days before that because on Friday the 7th, we had a launch rehearsal where we went through all of the comms that would happen on the way to the countdown, et cetera. Then I was back of Blue Origin again, Saturday the 8th for a press conference and also for the launchpad tour. And then we went back again for the first launch attempt on the 9th and there were squalls of rain coming in and the weather officer was saying, "This isn't looking very good." And then also a cruise ship wandered into the launchbox on Sunday as well. And we were like, "What? How can that happen?" And there were other fishing boats. And so the launch on Sunday was, I don't know if cursed is the right word, but it just wasn't going to happen on Sunday. So then the wave heights were too high for a landing attempt, I believe, on the Monday and the Tuesday. And so Wednesday was going to be the next attempt. But then on Tuesday morning, we started seeing these big coronal mass ejections coming off the sun and there were warnings that there was going to be a major space weather event on earth. And so throughout Tuesday, we spent a lot of time looking carefully at the projections for the CME encounter with Earth, for it to impact Earth. And we spoke at length with some of the space weather people at the Moon to Mars Space Weather Analysis Office at Goddard because these people, they work shifts until midnight every day, and their job is to analyze and predict potential space weather events. So between talking with those people, looking at what's called SWPC or SWPC, this is the NOAA website, that tracks space weather. We determined that not only was the level of charge particle radiation in Earth's radiation belts really, really elevated, like elevated by a factor of a thousand from its baseline, and up to a level that was already too high. But then we saw that there was another coronal mass ejection shock due to strike earth right at the time of what launch was going to be on Wednesday the 12th. And so we just said, "Look, our official recommendation is that we don't launch into this." Because the nightmare scenario would have been when we deploy the spacecraft from the New Glenn upper stage, the solar arrays are supposed to autonomously deploy. There's a sequence that begins as soon as the spacecraft power up. But if you're in a radiation environment that's too harsh or hostile and you're constantly getting spacecraft computer resets over and over again, there's a nightmare scenario where those panels just never deploy. And after six hours, the batteries are dead and your mission is over. And so we brought this up as an unacceptable risk. NASA were in full agreement with us. We walked through this with Blue Origin. They completely understood. And so launch was postponed until Thursday. And then as you saw on Thursday the 13th, the launch went off. After there was a brief hold, it was meant to be 2:55. It ended up being 3:55, but it all went off great, 3:55. And everything after that was perfection. Everything went exactly as it was meant to.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It really did though. I felt like a silly person in my apartment cheering at the top of my lungs, listening to the livestream, but it went off absolutely flawlessly, which after seeing what's happened with all of the other missions as part of the SIMPLEx program, so many of them have gone through hardships. And so far, this is the one truly successful part of the program. So I've just been rooting for you guys. It felt so cathartic to finally see those probes just launch out into space.

Rob Lillis: And not only that, it turns out that the injection Blue Origin gave us was so accurate that we can postpone our initial trajectory correction maneuver for several weeks because they gave us ... It was fractions of a sigma in terms of the accuracy. It was almost like that, famous the Ariane 5 that they gave to give JWST the perfect injection, it was like that. So I mean, huge props to Blue Origin for building an amazing launch vehicle and giving us a perfect ride.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's very useful in this case for several reasons. I mean, you were initially going to rideshare with Rocket Lab's Photon launching on Psyche, I believe, on a Falcon Heavy, and things have changed in the meantime. Now you're launching on a New Glenn.

Rob Lillis: Yeah. So actually we did not start with Rocket Lab until after the decision to remove us from the Psyche mission occurred. That was in the fall of 2020.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But now instead of launching within the normal launch windows to Mars, you're doing something very interesting, which is that you're going out to L2, you're going into this loiter orbit, and then you're going to be basically slingshotting around the earth in order to get to Mars. So everything about this orbit is very different from the way that we usually launch to Mars. And I imagine having that extra accuracy, that extra fuel might really help as you try to pull this maneuver off.

Rob Lillis: That's exactly right. Yeah. So we have this kidney bean shaped so called loiter orbit, which takes about 12 months. So we go up to about three or four million kilometers away from the earth. We don't hang out at L2. We kind of go around L2 a couple of times, and we pass pretty close to the moon at one point as well. And then yes, as you say, on November 7th, and then again on November 9th of next year, we will be coming down to a very low perigee, only five or 600 kilometers. We're going to be burning the engines at that point, taking advantage of that deep gravity well so that our burn is extra efficient and we'll be slingshotting out into our interplanetary trajectory at that point to head off to Mars during that home and transfer window during which an Earth to Mars ballistic trajectory is possible.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And this is just harkening me back to my Kerbal Space Program days, but pulling off an Oberth maneuver in order to try to get to Mars is so clever. And it occurs to me that we've been locked into this 26-month period of launching to Mars because of these limited launch windows, because of these planets and their positions relative to each other. But because you guys faced this hardship, you had to figure out how to get to Mars outside of that window, now you've opened up an entirely new way for us to think about these launch timings. And perhaps even make a scenario which we can save a lot of fuel when we're trying to launch these places by leveraging the earth's gravity. It feels like this is such a clever way to go about this and could completely change the paradigm on Mars launches and even launches to other worlds even further out.

Rob Lillis: Yeah, that's right. They say necessity is the mother of invention, and that's exactly what we had to do. We had to come up with a way to get to Mars that was flexible. And we worked together with our partners at Advanced Space LLC in Westminster, Colorado to come up with this design. And it's a flexible design because based on the exact size and shape of this kidney being shaped orbit, we could have launched as early as May 2025 and as late as March 2026 and still been able to execute this circuitous path around L2 a couple of times back to do this Oberth maneuver without the date of that Oberth maneuver ever-changing. It was always locked November 7th and 9th of next year. And yeah, this does open up a brand new way to think about sending payloads to Mars because Earth only has so many launchpads. And if you have to launch everything that you want to send to Mars within one launch window, that launch window might only be three or four weeks long, there could be weather delays, hurricanes, et cetera. If you want to send dozens or hundreds of things to Mars would be necessary for the human settlement of Mars in the future, you can't really do it all within that narrow window, but you could launch over the course of many, many months and kind of queue them up so that they could come in and do their Oberth maneuvers and slingshot their way onto their interplanetary trajectory one after another, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. And that way you could send an Armada to Mars that you can launch over the course of 10 months instead of just one.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, these spacecraft are clearly designed to deal with space weather once they're actually out at Mars, but solar maximum is really popping off right now. Is there any concern that while you're out there at that loiter orbit that these spacecraft could be any way damaged by some kind of CME while it's closer to earth?

Rob Lillis: No, we're not really worried about that because we have a very robust fault protection system on board. They're very fault-tolerant. Both we have redundant flight computers so that even if one resets and even if it latches up, we can always go flip over to the other one. So space weather doesn't bother us, we know what the total radiation dose likelihood is over the course of this mission taking account of all those CMEs and we're confident that the shielding solution we have on board is going to handle that. The reason we were so worried about after launch was, as I just mentioned, when you're doing those really vulnerable early commissioning maneuvers to get yourself deployed solar panels, find the sun and become stable and power positive. Doing that in the middle of a radiation storm was not something we wanted to do. But now there's no space weather event that we're afraid of now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, now we're just counting down to next November so these things can make their way to Mars, but once they get there, how are these two spacecraft going to be timed in their orbit around Mars so that they can get a better understanding of how the entire system interacts with the solar wind?

Rob Lillis: Before we get into our science orbit, we do have to be captured by Mars's gravity. So we got to do this Mars orbit insertion, and that's also fixed for September 7th. Then September 9th, 2027 will be captured into a large orbit, and then we will spend several months reducing the sizes of the orbits and then also synchronizing the orbits because the arrangement of the two spacecraft in orbit around Mars has to be very precise to do the kind of science we want to do. In particular, we call it the string of pearls or science Campaign A, where the two spacecraft are essentially in the same orbit following each other, and it takes time to get into that orbit. And also there's a particularly long solar conjunction that occurs late in 2027 when the sun comes between Earth and Mars, and this is a particularly long one. So there's a whole month where we can't talk to the spacecraft. Anyway, once we get into 2029, sorry, eight, and we get into this string of Pearl's orbit, now we'll be set up so that we can really for the first time understand how Mars's upper atmosphere and its magnetosphere and near space environment varies on timescales of minutes because those are the timescales that we know the system must actually vary on and respond to changes in the solar wind on. Whereas up until now with only single spacecraft mission that could measure plasma parameters at Mars, such as Mars Express or MAVEN, you had to wait four and a half hours before you came back to the same place in the atmosphere. And things can change a lot in the solar wind in four and a half hours. So having the two spacecraft in this same orbit will allow us to say, "Okay, the conditions are X at this point and say three minutes later, the conditions are now Y, or maybe they're still X and maybe they haven't changed or maybe they have." And that time separation between the two spacecraft between the Blue and Gold probes is going to be varying between two minutes and 30 minutes back and forth. So their orbits are almost identical, but not quite so that the relative positions in the orbit will slowly drift with respect to each other to give us a range of different time separations so we can really characterize the system on that range of different timescales.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of our celebration of the ESCAPADE launch after the short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here, CEO of The Planetary Society. We are a community of people dedicated to the scientific exploration of space. We're explorers dedicated to making the future better for all humankind. Now as the world's largest independent space organization, we are rallying public support for space exploration, making sure that there is real funding, especially for NASA science. Now we've had some success during this challenging year, but along with advocacy, we have our STEP initiative and our NEO Shoemaker grants. So please support us. We want to finish 2025 strong and keep that momentum going into 2026. So check us out at planetary.org/planetaryfund today. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you've worked not only on MAVEN, but also on the Hope Mars orbiter and now this mission. And each of these missions in some part is trying to contribute to this mystery of how Mars lost its atmosphere over time. So what have we learned from these previous missions and how is this new spacecraft going to add onto that in such a way that we're going to learn things that we did not know before?

Rob Lillis: Okay. Well, certainly the MAVEN Spacecraft and the Mars Express spacecraft and the Hope Probe from the UAE have all contributed in their own way. MAVEN is still collecting very useful data on an atmospheric escape because this particular solar max is much larger than the previous one that MAVEN arrived at the end of and didn't really catch much of. So MAVEN is characterizing atmospheric escape at Mars at much higher solar activities than it has up until now. And MAVEN can characterize many different kinds of atmospheric escape, both the escape of oxygen hydrogen in its neutral form, but then also in its ionized form. And the Hope Probe is able to see at much larger distances away from Mars because it has this very, very long orbit, this 55-hour orbit. Hope is able to see the extended oxygen, what's called corona or extended exosphere of Mars. And being able to see that far out lets us more accurately determine what the rate of oxygen escape rates are. So combining Hope and MAVEN is really helping us to understand what I might call the kind of average state of atmospheric escape of Mars. Okay, what do I mean by average state? It's because when you only have one observation platform or viewpoint at a time, you can say, "Okay, well, when the solar wind is at this particular speed, we see the ion escape rate at this particular level." But you got to wait two hours between when you measure the solar wind and when you measure the ion escape rate, because you can't be in two places at once. And Hope cannot measure ion escape. It only measures neutral escape. But with ESCAPADE, we're going to be able to be in two places at once. And that's a good segue into describing our second science campaign, which is a science campaign B, which is where the two orbits are now of different sizes, therefore different periods. We're at the end of science Campaign A, we're going to raise the apoapsis, meaning the highest point in the orbit of one spacecraft and lower the other one. So now with the two spacecraft in different period orbits, they will now be able to precess with respect to each other. This will allow the two spacecraft to be much further apart from each other so that we can simultaneously measure the upstream conditions and also the downstream conditions. So we can simultaneously see the cause and the effect at the same time. Whereas with earlier emissions, we had to wait a couple hours. Whereas we know from all of our simulations, all the physics, we know that it should be changing on a timescale of a minute or two. So we'll have that ability to unravel that chain of cause and effect for the first time with ESCAPADE. And that's how it'll build on these earlier emissions.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think that was one of the things that you said in your conversation with Mat that blew my mind most. The fact that this entire system changes over the scale of minutes is absolutely mind-blowing when you think about it.

Rob Lillis: Yeah, that's right. And it's a consequence of the fact that the solar wind is moving at 400 kilometers per second. And so if you take Mars itself, Mars has a radius of 3,400 kilometers, and even the area around Mars, it's not that big compared to a solar wind proton traveling that fast. So it only does take about a minute, two minutes for the effect of any particular solar disturbance to propagate through the system. Now, there's still some debate as to, well, is it quite that fast? How quickly does it take for the magnetic fields that are embedded within the ionosphere to completely turn around? That's probably more than a couple of minutes. It depends how deep you are in the ionosphere. There's something we call magnetic fossil fields, meaning that they kind of hang around longer and it takes longer for them to change. So there's a lot of unknowns there that ESCAPADE is going to start to be able to unravel because up until now, it's just been simulations and one measurement every four hours. Now we're going to be able to have two measurements in quick succession, and that'll really help us unravel this highly dynamic, complex system that is the Mars upper atmosphere.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, Ari spoke with us a little bit about the VISIONS instrument and about the images that they're going to be taking from these spacecraft, but there are several other instruments on board. Can you tell us a little bit about what kind of instruments are on these probes in order to allow us to do this kind of study of the atmosphere?

Rob Lillis: Yeah, sure. So ESCAPADE's basic instrument suite consists of four instruments. The first is what we call a Langmuir probe, and this is actually four different sensors which together measure what we call the thermal plasma. So this is the low energy, what we say is cold plasma in the ionosphere. This is electrons and ions. We have separate sensors to measure the electrons. Those are these four little needles that are on our extendable deployable boom. Those needles measure the current from electrons, and that allows us to determine the electron density. We also have these little golden squares on the spacecraft deck called planar ion probes, and those collect currents from ions. And by measuring that current, we're able to determine the ion density. And then lastly, we have what's called a floating potential probe. It's this shiny golden sphere at the end of a stick. It's actually very distinctive. You'll notice a lot of the pictures in the media taken out of the ESCAPADE probes in the cleanroom at Rocket Lab were often, there were engineers looking at their own reflection in this little golden sphere. That measures the relative potential of the spacecraft, meaning the electrical potential. So we can see whether the spacecraft is charging up or charging down. That's important because if the spacecraft charges up and it's, let's say, electrically positive, that's going to affect how we measure ions and electrons because those will be either repelled from or attracted to the spacecraft depending on how charged up it is. So the floating potential probe or FPP, that's going to measure that. So that's the Langmuir probe. Our Langmuir probe was provided by Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida. So shout out to them and Dr. Aroh Barjatya, who's the instrument lead there. Okay. Moving on to the magnetometer, it was provided by Goddard Space Flight Center. The PI is Dr. Jared Espley there, and Goddard make fantastic scientific magnetometers. They made the MAVEN magnetometer, and this is simply a miniature version of the MAVEN magnetometer. And it is at the end of our two-meter deployable boom to get it as far away from those electrically noisy solar panels as possible in order to make the kind of really sensitive measurement of the magnetic fields that we see at Mars. And it needs to be not only sensitive, but needs to have a wide dynamic range because it could see magnetic fields as little as half a nanotesla and as much as a thousand nanoteslas. And so it's an instrument that's designed to operate in the martian environment. Lastly, we have our two electrostatic analyzers. These are built here at the UC Berkeley Space Sciences Lab. And one of them measures higher energy electrons and the other measures high energy ions. But as opposed to just measuring their densities, we need to measure their energy spectra and also their angular distribution. So these instruments have to be able to measure electrons or ions coming from all directions at all different energies. And it's a very ingenious design that was pioneered here at Berkeley in the early 80s and has evolved since in order to do that. And lastly, they can also measure the different masses of ions because we want to know whether it's protons, whether it's helium, whether it's carbon, oxygen, oxygen two, or CO2. So all those different masses of ions from mass one atomic mass unit up to 44 atomic mass units, we can distinguish all of those as well. So we can really tell not just that something is escaping from Mars, but what is escaping? Is it CO2? Is it oxygen? Is it carbon? So our instrument suite is going to be able to do that. And then of course, as you mentioned, we have our cameras from Northern Arizona University. They have two lenses on each one. One is a visible camera, pretty similar to what's in your cell phone, except obviously a very high quality charge couple device, CCD, very sensitive device, and of course ruggedized for space. And then separately, we have a microbolometer array to take infrared images as well, so both visible and infrared. And not only are we hoping to do a little bit of Mars surface science, for example, to determine things like surface temperature on Mars, but we're hoping to be able to see Martian aurora on the night side too. And the Perseverance Rover was able to, for the first time earlier this year, image Martian aurora from the surface of Mars in the visible. And we have measured ultraviolet aurora from several spacecraft in orbit, but we've never measured visible aurora from orbit ever before. So we're hoping that the ESCAPADE cameras are sensitive enough to do that. Our calculations say they should be, but we won't know until we see it and fingers crossed, but we're really excited to get this instrument suite in orbit around Mars to start doing the science that we need to do there.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, there's so much going on in Martian aurora science over the last few years that result from Hope about the proton aurora on the sun side of the world. It's absolutely mind-boggling. So I think between all of these different spacecraft together, we're going to get a much better, not only picture of it mentally, but maybe actual pictures. Oh, that'd be so beautiful. But we have two spacecraft here. We're going to know a little bit more about what's going on in the locations where those spacecraft are, but using these two probes, can we then extrapolate out to the larger system of how more broadly ... I mean, it's not like there's a really strong global magnetosphere on Mars, but just the entire system and how it interacts with the solar wind. Are we going to be able to get a more 3D understanding of how that happens?

Rob Lillis: Yeah, certainly. As I mentioned earlier, just being able to have two measurements at the same time will enable us to build up a better idea of what Mars's 3D magnetosphere looks like at any one time. Of course, it's not the same as having 10 or 30 probes, but it's so much better than having one. And speaking of 3D understanding of this dynamic system, we have two different types of global simulations. We have different team members who run different codes. One is called a magnetohydrodynamic code, and another one is called a hybrid code that deals with electrons as a fluid and ions as particles. And we have team members from France, from UCLA who are going to be running those models. And those models are going to be really important context because A, we'll be able to at least say that, "Well, if the conditions where the two spacecraft are, if those are accurately reproduced by the models, we can be reasonably confident that the models are probably accurate elsewhere." Now, that's going to be true sometimes, but I guarantee you other times the models are not going to be able to capture the dynamic situation at Mars. And so we're hopefully going to be able to improve the models because the models aren't perfect either. There's a famous saying, "All models are wrong. Some models are useful." But those sorts of physics-based global simulations of the planet combined with our multipoint measurements will definitely enable us to get a much better 3D picture. And the reason I stopped myself there was because I wanted to say it isn't just going to be ESCAPADE. We're going to have MAVEN as well. And it's almost like MAVEN is the big sister and ESCAPADE Blue and Gold are the two little brothers who are showing up to take their place in what was increasingly becoming a Mars space weather constellation. And we additionally have the European Mars Express spacecraft still soldiering on 22 years later. And we're going to have another edition, which is the Japanese Mars Moon's explorer mission, MMX. It's going to be launching in late 2026, and it's going to be hanging around Mars's moon, well, it's going to go to Deimos first, but it's going to actually sample Phobos and it's going to be orbiting there. It's going to be measuring the solar wind and the magnetic field for about three years there too. And lastly, we have China's Xianguan one probe as well, which is also measuring a magnetic field. And the Chinese scientists, they've been making their data public and there's already publications showing up from scientists all over the world using data from both MAVEN and from Tianwen and from Mars Express. And so we're going to be adding three more spacecraft, both ESCAPADEs and Japan's MMX. So it's going to be a golden era of understanding of the Mars near space environment and how it responds to space weather.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, this is such an important part of the Martian kind of ecosystem that we need to understand better, not just because we want to know how it lost its atmosphere over time and its potential for habitability in the past, but there's so much discussion about potentially sending humans to Mars. And it's so important that we understand what's going on with the solar wind interactions there because if we want our people in space to be safe, we need to have this kind of information, especially during solar maximum.

Rob Lillis: Yes, we sure do. And the data ESCAPADE is going to be collecting and the knowledge ESCAPADE will be contributing to are really relevant to the project of sending humans to Mars in a few different ways. I mean, one, we're going to have a multipoint additional pair of observations to understand how the solar wind interacts with Mars. We're going to be able to measure those high energy particles that can cause human health concerns. And we're going to have just additional points in the solar system to understand how those big coronal mass ejection shocks that carry so much high energy particle radiation, how those propagate throughout the solar system. So we'll actually have the measurements ESCAPADE going to make on the way to Mars as well as the measurements that it makes at Mars. So that's from an astronaut health perspective, but we also have a communication issue as well because Mars has a very patchy ionosphere and a much less well-understood ionosphere than Earth does. And when we want to navigate on Earth, when we want to use GPS, the GPS signals that we use in our phones on Earth are automatically corrected for ionospheric perturbations in a way that's totally invisible to us. The users, as we're holding our smartphone and we see that little blue dot correct within a couple meters usually, the reason that that's possible is because we understand how the ionosphere distorts those signals on earth. And when we do have a big solar storm, the accuracy of GPS does tend to go down. Although because we have good monitoring, we can keep track of how that distortion is changing. On Mars, we really don't have a good understanding of the variability of the ionosphere. So the ESCAPADEs passing through that ionosphere twice in quick succession during our Campaign A is going to give us really our first look at how the ionosphere changes on those timescales and therefore will give us in the future an ability to accurately estimate how radio signals are distorted as they propagate through that ionosphere. And so that's important for navigation, but also just for communication too, particularly if you want to use short wave radio, let's say you have two settlements on Mars that are a couple thousand kilometers apart, they want to talk to each other, you can use satellites, you can try to use the ionosphere to bounce the signals off as we do on Earth. So understanding the Mars ionosphere better is going to be really important for understanding how radio waves propagate for both communication and also for navigation.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, once these spacecraft actually reach Mars, how long are we expecting them to survive and be taking good data?

Rob Lillis: So NASA has approved an initial 11-month science campaign beginning in June 2028 going until May 2029. However, we have designed the spacecraft to last at least five years from launch, so launch in 2025, so at least until late 2030. But spacecraft tend to have a habit of lasting longer than you plan because engineers are pretty conservative. And so just because our batteries might degrade a little bit more over time, we just got to be nicer to them. I mean, this is true for all aging spacecraft. Same thing is true for the solar panels. They're going to be a little bit less efficient, but that's just normal. That happens over time. And the fact that we have spacecraft like Mars Odyssey, which is over 100,000 orbits now, we have Mars Express, which is only a little younger than Odyssey. We've got Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, still mostly going strong. We're confident that Rocket Lab have built us a really good pair of probes. And if we can get them into Mars orbit, we're confident though they could last a very long time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And on such a smaller budget compared to so many of these other missions because you're part of the SIMPLEx program.

Rob Lillis: That's right.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: If you guys pull this off, it is going to be paradigm changing.

Rob Lillis: Yeah, I think so. I think if you take the costs of previous missions, they are about 10 times what ESCAPADE will have spent, at least on the spacecraft. And I know it's not exactly apples to apples. ESCAPADE's instruments were very high heritage and simple, and there were fewer of them compared to, for example, MRO or MAVEN. That being said, doing an entire mission, we at Berkeley and Rocket Lab, we delivered these two probes for the original launch attempt in fall 2024 for $49.3 million, which is about a 10th of what it would've cost doing it the usual way. And there were a few different reasons for that. One was that, as you said, the SIMPLEx program was meant to be a lower cost program where NASA exercises less oversight. NASA required far smaller amounts of documentation. There wasn't as many reviews where they have to go with a fine tooth comb through all of your data to really be convinced that things are as you say they are. There's just more trust placed in the project team. NASA says, "We trust you, you're the experts. Obviously, we'll still keep an eye on you, of course. We'll still have reviews, just not the same level of oversight as before." And the same was true for the launch contract, a so called VADR, Venture-Class Acquisition for Dedicated and Rideshare. I know, it's a tortured acronym. This is another way in which NASA has procured lower cost launch vehicles too with also less oversight than usual. And you should probably get someone from NASA's launch services program in some day to go through what that has meant for the launch business. But then also Rocket Lab, they operate under a firm fixed price, vertically integrated off the shelf, commercial forward way of doing things whereby they can just get things done for a much lower cost because they've embraced efficiency. They have far fewer subcontractors because they have just either learned how to do everything in house or they've purchased these other companies to bring them in house. And so they have a lot more control over their schedule when literally the people making the solar panels are also the same company. And one great example of where that really shone through was the fuel and oxidizer tanks. During our development phase, they were being procured from a subcontractor, and that contractor was having difficulties. They had personnel issues, they had issues with their building, and they were falling really far behind, and we were getting really nervous. Us and NASA and also Rocket Lab were getting very nervous about these tanks being delivered on time for the original launch attempt in fall 2024. And Rocket Lab, they saw this and they said, "We really need more control over this." So they spun up an effort to make the tanks in-house with their 3D printing technology, and they were able to essentially make the tanks in-house so as not to need this external vendor. And they did all that within just a few months. We were really, really impressed. I was quoted in the media last fall as saying that Rocket Lab went into so called hero mode to go recover from that tanks issue. And it's just an example of where the new space companies like Rocket Lab can be more nimble. They can fix problems faster and they can deliver a great product for a much lower price. And this is what's going to be, I think, greatly enabling for these sorts of missions in the future. NASA's always going to need the big flagship missions to do the really, really hard things, and those are great. But I think a larger proportion of NASA's budget can go to a much larger number of lower cost missions. And this is something which the new NASA administrator nominee Jared Isaacman has said over and over again in his posts on Twitter, public remarks, et cetera, had a chance to speak to him at the launch. And he said the same thing there. He's been consistent. And so hopefully we can get to a place where we're having more missions like ESCAPADE.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I would love to live in a future where we have probes around every single world in our solar system and whatever kind of technology and funding process we need to go through in order to enable that, I'm here for it. So all the missions across the map, let's do it.

Rob Lillis: Absolutely. Yes, yes. And look, I think fixating on a particular price point, like a hundred million, that's definitely useful. There's a lot of great science you can do for a hundred million dollars. There's also plenty of signs that you just need two or 300 million for. So every mission shouldn't be a hundred million. There are certain things that are just harder and that are still very much worth doing that are at higher price points, but every mission can be done more efficiently than it is being done now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I want to say congratulations to you and the entire team for pulling this off. I've been so excited about this in part because UC Berkeley was my alma mater. Go Bears. Knowing that there's going to be probes going around Mars name for the Blue and Gold makes me just personally very happy. But also these are such deep questions that have huge implications for our future exploration, not just for probes, not just for our understanding of that world, but for the future of human exploration to Mars and across our solar system. So I'm just so looking forward to seeing what happens once these missions get there. And I would love to bring you back on once we know a little more about the atmosphere to actually piece apart some of the results, because I think it's going to be really interesting.

Rob Lillis: I would be delighted to come back in 2027 and talk to you some more about that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Absolutely. Well, thank you so much, Rob.

Rob Lillis: Okay. Thanks, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Even though Mars doesn't have a global magnetic dynamo, it does have remnant crustal magnetic fields and an induced magnetosphere. This strange magnetic environment is what allows Mars to produce auroras. They happen mostly on the night side, but sometimes they happen in unusual forms like proton auroras on the day side. Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist is here to discuss in What's Up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hello, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I had a really fun time watching the ESCAPADE launch. Did you get a chance to watch that live stream?

Bruce Betts: No, I did not. I apologize. How'd it go? I mean, was it fabulous? Was it enjoyable? Did you love it?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, honestly, I don't want to put it this way, but it went way better than I thought it would because it's only the second successful launch of the New Glenn rocket, and they absolutely nailed that landing. And that's a hard thing to accomplish, especially with all these other things going on. You got solar storms and I just, I don't know, it was really thrilling after all of the delays. Plus part of what this mission is going to be doing in order to learn more about the interaction between the solar wind and Mars is that they're going to be trying to look for auroras on Mars. And as I was learning more about this, I learned from some data from some European missions, but also from the Emirates Hope mission to Mars that most of the auroras on Mars happen on the night side. Why is that?

Bruce Betts: Partying.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Partying.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, they party more at night. They're chilling hard. Okay, I'll stop.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That tracks.

Bruce Betts: It's complicated. Mars has only got remnant crustal magnetic fields. Now it has no global magnetic field. Once upon a time, it had magnetic field. And when the lavas were coming out, they froze the magnetic field in it. So there are these localized small magnetic fields, but overall you don't have one. And so things work very differently than on a planet like Earth or Jupiter or Satan, most of the other places that have a strong internal magnetic field. So you actually end up with things that are a little different.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So how does the solar wind actually get around Mars and reach the night side?

Bruce Betts: So solar wind, the charge particles from the sun can wrap around the planet and go party, as I told you it was party, party in the magneto tail. So the part that gets stretched out behind the planet of the magnetic field lines, and they're able to get in there and weasel their way in and abuse the atmosphere in somewhat different ways. I'm trying to use as much technical jargon as possible. Let me know if I lose you. Those are the draped field lines, and they're the open field lines which connect Mars with space directly, kind of like your brain, I feel like.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right in the middle. This is why you need the tinfoil hats to block the...

Bruce Betts: I can neither confirm nor deny.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So basically the electrons from the sun reach the magnetopause and then they penetrate down into the atmosphere on the night side?

Bruce Betts: So the night side ionosphere is weaker than the day side ionosphere. So the electrons can go play lower down and there's also less atmospheric fluff because the sun's UV is not hitting it, so it's not inflating the atmosphere. So they're even getting deeper down in already thin atmosphere. And then the crustal magnetism has effects where you create hotspots and places where you concentrate things due to the very non-uniform magnetic field of the crust. So you end up seeing types of auroras as well, which are not something that we see elsewhere because of things like the effects of the crustal magnetism, the ionosphere, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. Okay. So that having been said, we come back to the weird proton aurora where you can get day side protons that are ... Solar wind is mostly protons, but then they do a little party with the hydrogen in Mars's upper, upper, upper, up atmosphere. And anyway, they become things that party down and make an aurora because on Mars, you're not going to see it because of the sunlight overwhelming it just like on Earth in the day side with our visible focused eyes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it was one of my favorite results that came out of Emirates Mars mission, the Hope Probe, was learning more about the aurora on Mars and those really weird proton auroras. I'd never heard of anything like that before, but each and every world's aurora is completely different. And it's strange to me that these aren't gathered around the poles. I mean, apart from the fact that I guess the strongest bit of magnetic field localized on Mars is near the South Pole, but that's not because of a global magnetosphere. It's just weird that worlds that don't have a global magnetosphere can still have these effects.

Bruce Betts: It is weird. And that's true basically of Venus as well, but there you get effects with interactions between the thick atmosphere and the solar wind. And solar wind protons and things, they party their atmosphere, but they come in, they follow magnetic field lines and they go usually party at the poles and every once in a while they get coronal mass ejections like we did recently where you can actually see them farther away from the poles. But usually they're being directed that way, but they're being directed by the global magnetic field that doesn't exist on Mars anymore.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I love that Ari pointed that out in the short conversation I had with him, that how funny it is that this mission that's trying to go to Mars to learn more about how solar storms interact with the atmosphere itself was completely delayed because of a solar storm. The solar maximum's wild.

Bruce Betts: Whoa.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right. So what's our random space fact this week?

Bruce Betts: Random space fact rewind. We're going far out of the solar system this time to the land of super crazy. The gravity at the surface of a neutron star is more than a hundred billion times the gravity at the surface of earth. Dun, dun, dun. Freaky, man.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Of all the things I wish we could get images of up close, it would probably be a neutron star because what even is going on there?

Bruce Betts: They are freaky weird.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right? I mean, degenerate, matter.

Bruce Betts: What'd you call me? All right, everybody. Go out there, look up the night sky and think about your favorite degenerate object. Thank you. And goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with even more space science and exploration. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Also, our holiday gift guide for space fans is out, so I'm going to link to it on this episode page just in case you need it. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place and space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email, [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our members all around the world. You can join us as we continue to advocate for even more missions to Mars and beyond at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are associate producers. Casey Dreier is the host of our Monthly Space Policy edition, which we're going to be postponing for one week until December 12th. And Mat Kaplan hosts our monthly book club edition. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. My name is Sarah Al-Ahmed, the host and producer of Planetary Radio. And until next week, add astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth