Planetary Radio • Sep 28, 2022

DART Impact and Judy Schmidt Interview

On This Episode

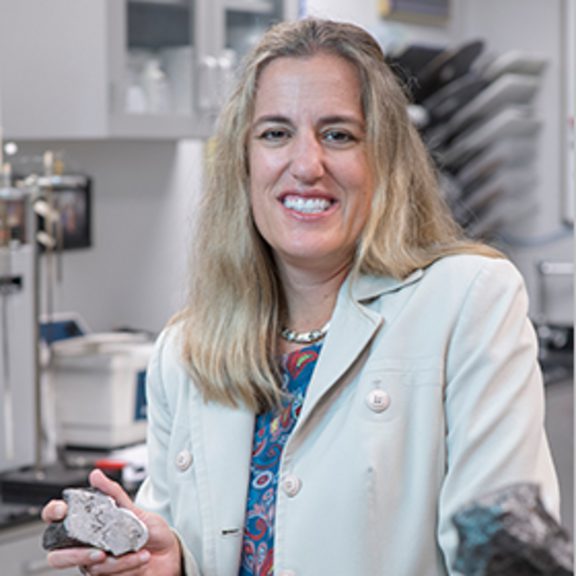

Nancy Chabot

Planetary Chief Scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, and Coordination Lead for DART

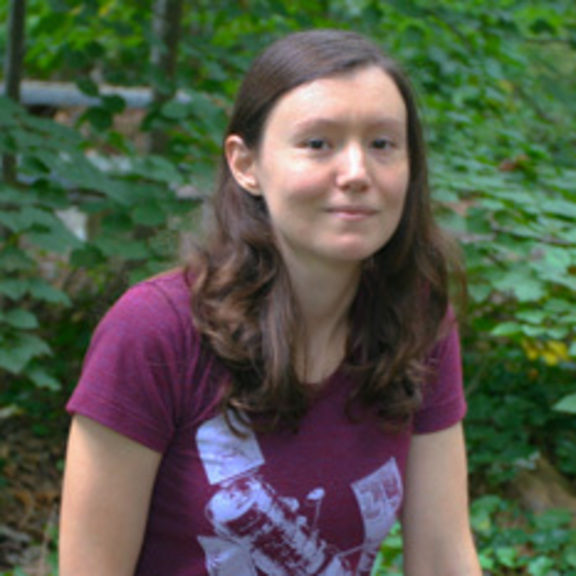

Judy Schmidt

Astronomical image processor and space artist

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

They did it! The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft scored a direct hit on Dimorphos. We’ve got the thrilling last moments before impact, followed by an exclusive, triumphant conversation with DART Coordination Lead Nancy Chabot. Then we’ll go from spectacular success to spectacular beauty as we meet extraordinary space image processor and artist Judy Schmidt. Bruce Betts salutes the DART mission with this week’s space trivia contest.

Related Links

- See DART’s final images before it smashed into an asteroid

- DART, NASA's test to stop an asteroid from hitting Earth

- Judy Schmidt’s spectacular Geckzilla Flickr page

- Glowing Dust of NGC628 processed by Judy Schmidt

- Follow Judy on Twitter

- The Planetary Society’s free “Basics of Digital Imaging” course taught by Emily Lakdawalla

- Elizabeth Howell talks with Judy Schmidt about how to edit JWST images

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

What were the proposed names for the two spacecraft that would have been part of the European Space Agency’s Don Quixote mission had it gone forward?

This Week’s Prize:

A Planetary Society KickAsteroid r-r-r-r-rubber asteroid, of course.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, October 5 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What is the approximate diameter of the crater made by the Deep Impact spacecraft when it impacted comet Tempel-1? Use the estimate enabled by a later spacecraft that flew by.

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the September 14, 2022 space trivia contest:

How long from its launch will it take South Korea’s Danuri mission to reach the Moon?

Answer:

South Korea’s Danuri mission will take 134 to 135 days from launch to arrival at the Moon. Go Danuri!

Transcript

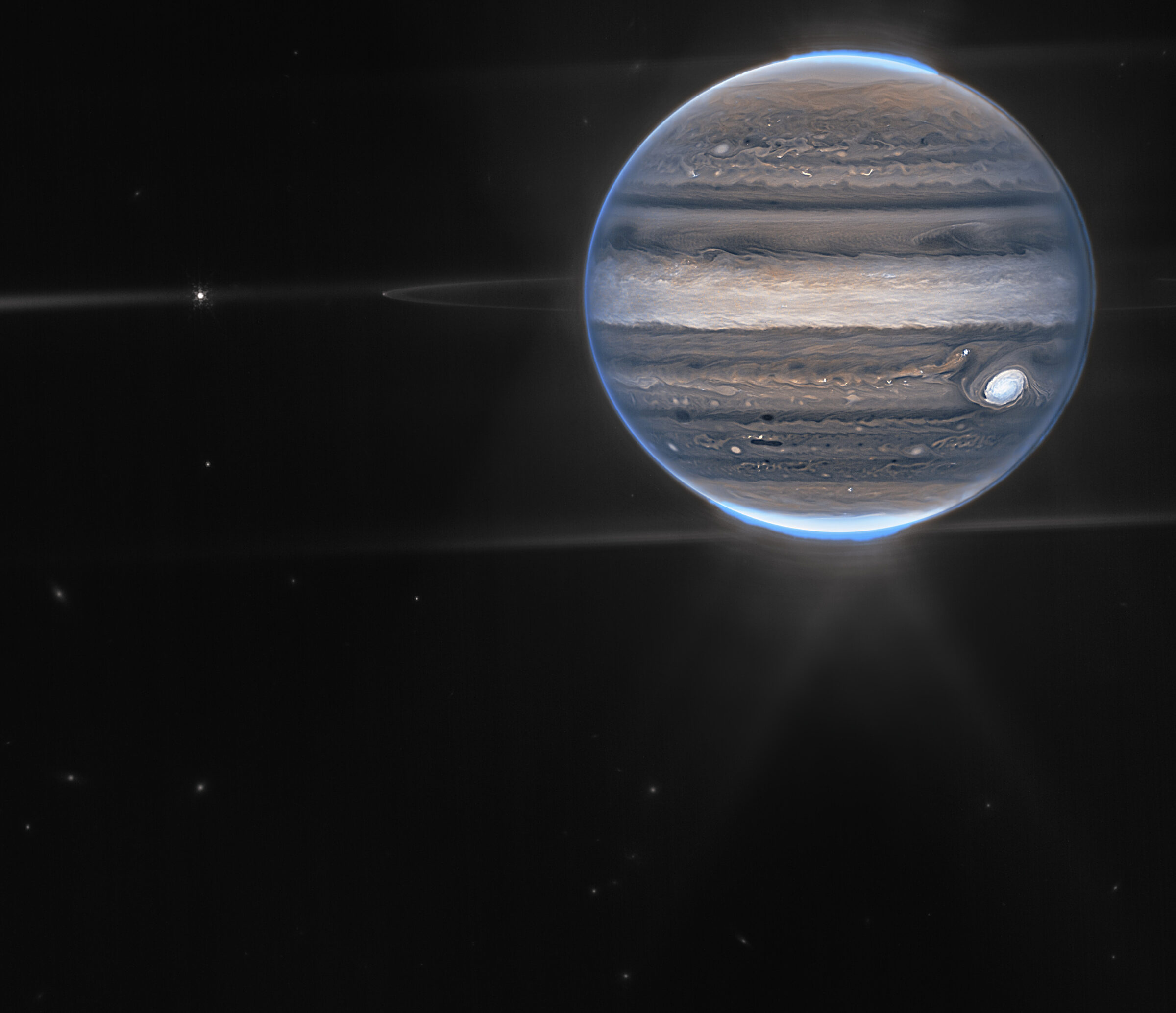

Mat Kaplan: Bullseye! DART hits its mark, and the artist behind that gorgeous image of Jupiter, this week on Planetary Radio. Welcome, I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. They did it, and they did it in the most spectacular way. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test spacecraft smashed into asteroid Dimorphos right on time, Monday, September 26th. We'll hear highlights of the last moments of its flight, and we'll get a post impact report from DART Coordination Lead Nancy Chabot. Then we'll meet Judy Schmidt, her name may not be familiar, but I bet her work is. Get ready for a charming conversation with one of our planet's leading amateur processors of astronomical images. Her work includes those stunning JWST shots of Jupiter that were featured everywhere a few weeks ago. Have no fear, Bruce is also here with his usual night sky survey, and a new space trivia contest that also celebrates DART.

Mat Kaplan: Can you hear it in my voice? I had a blast at last week's NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts, or NIAC Symposium, and you'll hear my coverage soon, but I started feeling unwell on the trip home from Tucson. You guessed it, I tested positive for COVID that evening. No worries, it has been a relatively mild case, and I'm hoping to end my isolation soon. As you'll hear me tell Nancy Chabot, it helped to be looking forward to that spectacular DART impact, which easily reaches the top of this week's space headlines. We'll also note that the Artemis 1 Space Launch System Rocket, and the Orion spacecraft made it safely back to the Kennedy Space Center Vehicle Assembly Building before Hurricane Ian hit Florida. Sadly, this means a more substantial delay in this uncrewed return to the moon.

Mat Kaplan: We've also got more proof that the JWST is good for much more than peering across the deep cosmos. Take a look at the September 23 edition of The Downlink, our free weekly newsletter, it features a spectroscopic examination of Mars by the big new space telescope. The data has already helped scientists gain new insights about the Red Planet. The Downlink also notes France's intent to increase space spending by a quarter to about €9 billion. The European Space Agency looks to do the same. There's much more to discover at planetary.org/downlink.

Mat Kaplan: Congratulations to the entire International DART Team on your knockout success. I was watching online with hundreds of thousands, probably millions around the globe, as the spacecraft closed in on Dimorphos. The last image relayed to Earth just before the spacecraft smashed into the 85 meter asteroid revealed a boulder strewn surface, much like what we've seen on Ryugu and Bennu. Those boulders didn't know what hit them. I've compressed the last 30 minutes of the mission into just over four. The first voice you'll hear is Mission Systems Engineer Elena Adams polling the key players. Also, featured from the Applied Physics Lab webcast is Lori Glaze, NASA's Planetary Science Division Director.

Elena Adams: This is DART MSE on DT MOC, it is time for the last status poll.

Lori Glaze: Yes.

Elena Adams: We're about, what? 7,000 miles from Dimorphos at this point? So, yay. All right, image quality, how are we doing?

Lori Glaze: Still looking very good. Dimorphos, still tracking along that same brightness predict as Didymos.

Elena Adams: That's great. All right-

Crew: Maneuver complete.

Elena Adams: Yes, thank you. All right. SMART Nav.

Crew: SMART Nav is looking nominal. We are at under 30 meters of projected miss distance right now.

Elena Adams: Yeah, it's looking really good. Look at that, that's looking fantastic. GNC?

Crew: GNC also looking good. We've been very excited to do those burns. We've been waiting a long time.

Elena Adams: Oh, this is great. Autonomy?

Lori Glaze: Autonomy is green, the heaters are cycling nominally, and we've had no new fault drills firing.

Elena Adams: Okay, wonderful. DSN?

Crew: DSN is green, and ISSA is green. We got plenty of margin. Looks good.

Elena Adams: All right. Ground systems?

Lori Glaze: Ground system has been helping a few users manage clients, but everything is going fine there, and we are green.

Elena Adams: Yes, wonderful. Thank you guys, it completes the poll. Last one. Last one. All right, so Dydimos is looking like itself, we'll see what Dimorphos is looking like soon.

Crew: MSE, this is SN5.

Elena Adams: Go ahead, SN5.

Crew: We are precision locked, and still tracking Dimorphos.

Elena Adams: Yes. So this was our last milestone, at this point, we're going to be working towards Dimorphos. I expect we are going to do some burns. We're about 4,500 miles away from Dydimos and Dimorphos, so let's see what happens. This is DART MSE on DT MOC. Five minutes till impact, five minutes till impact, we are at 1100 miles away. Also, our window for sending any commands to the spacecraft is done. Contingency is done.

Lori Glaze: 14,000 miles per hour, and remember 45 minutes ago, 55 minutes ago, we couldn't even resolve this object in space, and now we are ... you can see us zeroing in right on target. I think we're starting to see more resolution. In fact, look at that, Dydimos has even gone out of the view. We're now just seeing Dimorphos.

Elena Adams: Oh, my goodness. Look at that.

Crew: Looks like control system's settling down, angular rates look really good. I think we're going to get the investigation team some good pictures.

Elena Adams: No, no, come on, we can do better than that.

Lori Glaze: Starting to see those individual boulders there. We can see shadows, various rocks on the surface.

Elena Adams: 30 seconds till impact. It's amazing, guys. Oh, my goodness. Look at that. Unbelievable.

Lori Glaze: Yeah, looks to me like we're headed straight in.

Elena Adams: Oh, my gosh.

Lori Glaze: Oh, wow.

Elena Adams: Yeah. Oh, my goodness. 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Lori Glaze: Oh, my gosh. Oh, wow.

Crew: Awaiting visual confirmation.

Elena Adams: All right.

Crew: There's loss of signal.

Elena Adams: We got it?

Lori Glaze: Waiting.

Elena Adams: Waiting.

Crew: And we have impact, a giant leap for humanity in the name of planetary defense.

Elena Adams: Fantastic. Oh, fantastic. Oh, what team and what an accomplishment.

Mat Kaplan: Lori Glaze, Elena Adams, and others as DART hurdled toward asteroid Dimorphos. DART Coordination Lead Nancy Chabot has kept us informed about the mission for years. You may have caught my extended conversation with her on last week's show recorded as DART closed in. Nancy graciously allowed me to check in with her again, just a half day after the astonishing climax of the mission. Nancy, what can I say? Wow, absolutely astounding success. Congratulations.

Nancy Chabot: Oh, thank you. I think wow and astounding are just fine things to say. The excitement is still high here at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab where I am right now, the next day after what was a smashing spectacular success last night.

Mat Kaplan: A smashing success indeed. I would be shocked, I'd be so disappointed if people weren't still thrilled there. I just told you before we started recording that this has made my COVID isolation much more easy, because I had this to look forward to and then to celebrate as I, and gosh, hundreds of thousands, if not millions, watched it last night as we speak. That was just so exciting. Where were you when the impact happened?

Nancy Chabot: Well, I was here at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, and I'll just say that I hope you're feeling okay and doing well. It's a-

Mat Kaplan: Much better, thank you.

Nancy Chabot: It's the world we live in, but the world that we live in is an interesting place, right? There's low things and high things that we can all celebrate together. I think one of the things this morning that I really value about this, is that the team and the world experienced this moment together at the same time in all their different place. You were in your house. I was sitting actually at the NASA broadcast desk, which was a little surreal, because I was slated to go on right after that, and so they get you in that chair early, and you're sitting there, and it's me and the host, and some camera people, and we're all watching that TV there in real time.

Nancy Chabot: In this kind of isolated, quiet environment, we were celebrating our little team, but over here at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, you saw the Mission Operations Center, they were standing up and celebrating, and everything like that. There was a big watch party out here, and so people were outside. A lot of the team members were able to bring their families, and they were outside watching it here, and parties were around the world for watch parties with this, and I think everybody has a little story about how they saw this happen.

Mat Kaplan: Great job, by the way. I saw you at the anchor desk there, almost closing out the webcast last night, the live coverage. We actually had a recording one of my colleagues made, of that watch party that our boss, Bill Nye, had a part in, it was great to see him as part of that as well. You were watching as Lori Glaze, the Head of the Planetary Science Division was also blown away by that smashing success.

Nancy Chabot: Yeah, I think we all gathered here together, and the team has worked so hard in order to make that moment happen. It really has been years and hundreds, really actually thousands of people when you take our international team into consideration that have worked on this for years. Even before that, it was a concept that people wanted to do, so to have everybody come together for that moment, and we knew we were ready, we knew we had tested, but that doesn't change the fact that it was hard, and had never been done before, so there's nerves and anxiety, anticipation, and then just so much joy when those images came in, and they were beautiful. They were beautiful images. I mean, I just think about the team that built that camera here at APL, how proud must they be? The team that designed the autonomous navigation, right? It went right into that asteroid. Everything was fabulous.

Nancy Chabot: I will say, that people here on the science team, even though we had a big watch party here at APL with Bill Nye, like you said, some of them went up into their offices to start running models right away. They saw those first images and celebrated, and then they're like, "Let's get to work, understanding what this means." People have been waiting for this moment on both sides, from the technology establishing that you could target a small asteroid in space, and then on the science side, what actually happens when you run a spacecraft into an asteroid, and that's where we are now.

Mat Kaplan: The scientists must be thrilled by those last images, which looked a lot like what we got to see at Ryugu and Bennu, lots of pretty little boulders.

Nancy Chabot: Lots of pretty little boulders and rocks. I think one of the things that we've been talking about on the science side is, I don't know, maybe how unremarkable the shape is, that it's kind of like an egg, I guess, is what people are describing it as to a certain extent. We haven't done all the analysis in the modeling, but a lot of other objects that we've seen in space, they turn out to have these weird shapes. There was the Comet CG that Rosetta went to, Churyumov-Gerasimenko, and they called that the rubber ducky, and instead it's like you were just zooming in with those DRACO images, which were spectacular onto, sort of this mostly roundish kind of asteroid, and that's fascinating in itself.

Mat Kaplan: I'm also thinking now of [inaudible 00:13:13], which I was there at APL when those images came in, that big dog bone shaped object. Yeah, that's all right, Dimorphos doesn't have to feel ashamed because it has a boring shape. Do we have any idea yet what the scale of those images was? I mean, just how big were those rocks and boulders?

Nancy Chabot: Well, the final images that came out sort of show things at 10 centimeters, less than 10 centimeters sort of scale. You're really seeing these fine details down in those final images, but you came in really quick, so saying that isn't the ... the one second image before that was six kilometers further away, so your scale was quite different, but the final images there, and just that little partial image that came across has the highest resolution. It'll be fun that we have that data at so many different scales from just seeing it as a few pixels of a point of light, and then going into being able to see things that are the size of your hand.

Mat Kaplan: That was so poignant, that last image. I couldn't help but think of the DART spacecraft as trying to return one more image before it was vaporized, and that's exactly what happened, right?

Nancy Chabot: Oh, yeah. No, the DART spacecraft was on its mission, doing what it was designed to do, doing what it wanted to do in a lot of ways. This was its mission. This was its moment, all eyes turned on it while it accomplished it spectacularly, and it was working right up until the last second.

Mat Kaplan: So basically DRACO, the camera, and AutoNav, flawless, right?

Nancy Chabot: They worked fabulously. It's spectacular. The teams who did those should be really proud, as should everybody on this mission. I know I am just contributing my part to this much bigger project that took so many people to accomplish, and you test, you get ready, and then when it actually works like that, it's still special, even though that's what you had designed it to do.

Mat Kaplan: Do we have any word yet about whether LICIACube, that little Italian space agency CubeSat, was it successful in imaging the impact?

Nancy Chabot: Yeah, so we were celebrating those DRACO images in here, but LICIACube was still working, it was busy out there in space gathering those images, and they were lucky enough to get some downlink time, and get them back quickly. I think they just had a press conference actually that ended a few minutes before I'm here talking to you, where they showed some of those first images, and just seeing them there, I only saw them briefly, but they looked spectacular. It's tremendous. Were super happy and excited for our Italian colleagues, and we're excited for this international mission that is DART, and LICIACube, and scientists around the world for planetary defense for this international issue, and everybody working together to understand what this means for planetary defense, and potentially protecting the Earth in the future.

Mat Kaplan: Huge congratulations then to those folks at [inaudible 00:16:12] who pulled this off. I can't wait to see those images. I have not seen those yet. Any preliminary reports yet from ground-based telescopes that we're watching? I saw that even the Hubble and JWST have their eyes on Dimorphos.

Nancy Chabot: Yeah, so even last night, and especially on social media, the telescopes that could directly image the impact event, where in that position of the night here on the Earth, they started to post some images where they saw brightening of the system. The brightening due to that pulverized rock and ejected that was thrown off during DART's energetic collision with Dimorphos, and they noticed that in the telescopes, and it was fun to watch. Telescopes in these different locations continually post these pictures or these little short movies of that happening, and so that was an immediate confirmation. JWST and HST, they were looking too, and those data are making their way here, and people are analyzing them. I expect, probably in the next day or so we'll probably be able to get some results out from those, and then we need to figure out what the period change is. That's going to take a longer baseline so that telescope's got some initial work.

Nancy Chabot: They're still characterizing how long the ejecta will stay in the system, how long it'll take for that brightening to damp down, because you need that ejecta and brightening to damp down before you can make that measurement again of how much the period change was. Because you can't really make that sensitive measurement of Dimorphos going around Didymos if your system is super bright with all the dust all over the place. But, having the dust all over the place is a huge thing to study, we've always hoped for ejecta and dust that we could study and get information from that, and being able to get the period change as we go forward. It's hard to believe, it hasn't even been 24 hours since this happened because the data is coming in so quickly, and we're just excited about digging into it and figuring out what it means.

Mat Kaplan: But in some ways, from what you're saying, the most important data is still ahead to see if DART was successful in nudging this asteroid.

Nancy Chabot: Well, I think DART is already successful, so I'm going to quarrel with that phrasing of that question. I think DART successfully hitting the asteroid was really one of the main challenges. Even the mass that we were bringing in just with the spacecraft alone would've been enough to move the asteroid. I think the question has always been, "How much? How effective is it going to be?" That's where we're at, and so regardless of what that answer is, I don't think DART's success rests on it, instead that's the purpose of doing a test that's never been done before, and that's the information that we need to be ready going forward.

Mat Kaplan: I certainly don't mean in any way diminish the accomplishment that took place last night. It is mind-boggling, and I look forward to hearing those results of course, but aren't we still just at the beginning here? I mean, really, if we're going to do effective planetary defense based on this research, don't we need to do this five or 10 more times?

Nancy Chabot: Well, this is just one part of a larger planetary defense strategy, and DART is not something that you do in isolation. Fundamental to planetary defense is knowing where the asteroids are, and so we really need to have that warning time. Something like DART only works if you can do this years in advance, like you were saying, and so that's why it's got to be a priority for finding those asteroids, assessing them, and constantly identifying if there is a threat to the Earth, and then putting us in a position where we have the warning time to potentially do something about it.

Nancy Chabot: DART though, from being able to protect the Earth potentially from asteroids if a threat was found in the future, it's always important. We probably should say there are no known asteroid threats to the Earth from the ones that we've discovered so far. Earth has been hit by asteroids for billions of years, and this will continue though, so we want to be in a position to be ready, even though there is no known threat currently. DART was just the start. It's this first step of developing this technology. It's not the last step in developing this technology, and it's exciting that we live in this future where we've taken this first step, and ready to take more going forward.

Mat Kaplan: Nancy, thank you to you, the entire DART Team for helping us achieve this first step, with such excitement for people around the world, and thank you again for joining us, really just hours after this ... what did you call it again?

Nancy Chabot: A smashing, spectacular success.

Mat Kaplan: There you go. I hope that there is much more great data ahead of us in the coming days, and look forward to maybe welcoming you back to get a little summary once we have most of that data in. Thank you so much for, actually for years now, keeping us up to date on what's happening with DART.

Nancy Chabot: Yeah. Well, thank you for having me, and thank you for sharing it. I think that's really what we do these missions for too as well. Here on the team, we're just ... this is all part of something that we want to share with the world, so thank you for helping making that happen.

Mat Kaplan: You bet, and I will say it again, and I don't think it'll be the last time. Go, DART!

Nancy Chabot: Well, DART's done [inaudible 00:21:20], but the team is still busy.

Mat Kaplan: Double Asteroid Redirection Test Coordination Lead, Nancy Chabot. By the way, here's what you'd have heard at the APL watch party led by Bill Nye. Listen as the excitement peaks each time a new image appears on the big screen.

Speaker 6: Oh, my God.

Mat Kaplan: Did you catch the fireworks at the end? We'll turn in a minute to my lovely conversation with ace astronomical image processor, Judy Schmidt, stick around.

George Takei: Hello, I'm George Takei, and as you know, I'm very proud of my association with Star Trek. Star Trek was a show that looked to the future with optimism, boldly going where no one had gone before. I want you to know about a very special organization called The Planetary Society. They are working to make the future that Star Trek represents a reality. When you become a member of The Planetary Society, you join their mission to increase discoveries in our solar system, to elevate the search for life outside our planet, and decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid. Co-founded by Carl Sagan, and led today by CEO Bill Nye, The Planetary Society exists for those who believe in space exploration to take action together. So join The Planetary Society, and boldly go together to build our future.

Mat Kaplan: Want to get full benefit from my conversation with amateur image processor, Judy Schmidt? First, go to flickr.com and search for geckzilla. That's geck as in gecko, G-E-C-K-Z-I-L-L-A, or cruise through her Twitter post where she's @SpaceGeck. Judy is an amateur the way great amateur astronomers are amateurs, the only difference between her and a pro is that she does this work purely for love of the images and sharing them. I'd seen her credit many times, but it wasn't till the release of those beautiful infrared images of Jupiter that I knew we should talk. She joined me a couple of weeks ago from her home studio, where her new son, mercifully let us get through the entire interview. Judy, thank you for joining us on Planetary Radio. It really is an honor, and probably long overdue, getting to talk to the person behind so many of the beautiful, beautiful images, maybe they started as beautiful, but you certainly have enhanced a lot of them. Thanks for joining us.

Judy Schmidt: Thank you. It's good to meet you and be here.

Mat Kaplan: We probably should have met for other reasons as well. You've been writing, or you wrote a few years ago some pieces for The Planetary Society, and we'll link to those, and many of the other things that we talk about in this conversation on this week's episode page, planetary.org/radio. But people can also search all around the web for your work, it's not hard to find, and we'll talk about some of it, beginning right now with those JWST Jupiter images. To say that they are breathtaking, is really just to repeat what the entire world has been saying since you've published them. Congratulations on those. Have any of your past images received anything like this level of recognition and acclaim?

Judy Schmidt: No. No. I mean, there was one time one got on CNN, but it was barely a blip. It was a very popular image, but nobody cared or knew who I was, so it was just gravitational lens that looked like a smiley face, and people just went ... they're just like, "What?" It's called the Cheshire Cat and it looks like this big grinning face in space.

Mat Kaplan: My wife, who is not much of a space person, when I mentioned I'd be talking to you and I said, "You probably have seen her Jupiter images," she said, "Oh, yes, the ones with the great white spot." I said, "Well, yeah, in infrared it came out white, but usually it's red," and we had a great conversation generated just by that image. I think it says something about the power of these astronomy and astrophysical images to change people's thinking.

Judy Schmidt: Of course, yes, of course we've always had infrared imagery of Jupiter, but maybe it didn't quite captivate people because it was processed a little differently, or NASA does a Halloween Jupiter every now and then, and it's this sort of red fiery Jupiter.

Mat Kaplan: I've seen it.

Judy Schmidt: I mean, that one looks pretty cool, but at the same time it's like, "Okay, it's a single color image that's been mapped to this fiery color scheme," so maybe it asks fewer questions.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Judy Schmidt: It doesn't show the auroras, or it doesn't show the rings. You can still recognize the Great Red Spot, but not necessarily anything else, so I don't know why. It's a really good question, why suddenly everybody's like, "Wow, these images are amazing." I'm like, "They've long been amazing," but what is it about, maybe it's just the combination of it being the brand new JWST shiny telescope, and there's like all this for better or worse controversy about how long it took, and how much it cost. I'm not sure.

Mat Kaplan: You're probably onto something with that, but I also think that these are simply particularly stunning images, and that's not just me and a lot of other layperson space geeks talking. I have talked to quite a few planetary scientists, who are also just in awe of that set of images, and I think that you've made them feel better about their work as well.

Judy Schmidt: Really? Okay.

Mat Kaplan: So you are geckzilla in Flickr, and the reason that I mentioned that is that first of all, people ought to go there, and by the way, I didn't even know there was something called Flickr Pro, but I donated a month of Flickr Pro to you.

Judy Schmidt: It was you.

Mat Kaplan: You're welcome.

Judy Schmidt: I got that email this morning.

Mat Kaplan: It was nothing. It's very inexpensive, and I guess, it's a decent way to provide at least a little bit of support for the work that you're doing, that Flickr account, which of course we will also put up a link too on this week show page, it's just one stunner after another. It goes on and on, and the same is true for your Twitter account, @SpaceGeck, you have a thing for geckos, by the way.

Judy Schmidt: SpaceGeck was born because geckzilla was already taken for some reason on Twitter. It's some lady who hasn't posted in many years now, but I can't get the account name, and I thought, "What if I could get it, would I even change it?" Because everything links to SpaceGeck, so maybe not.

Mat Kaplan: Now, I think you absolutely need to keep this now, I love SpaceGeck and geckzilla. I do strongly encourage people to go there because there is image after image, we will only get to talk about a handful of them here, among the other topics that I hope to discuss with you. But really, folks, you got to take a look, and maybe check out that way of supporting her work. How did you get into this?

Judy Schmidt: About 10 years ago, ESA did a contest called Hubble's Hidden Treasures, and I was like, "Really? Everyone can download the data and just process it?" I had no idea, so I just started. First, I had to figure out how to find the data, which is, if you've never done it before, it's pretty daunting because I didn't know what any of the filters meant. I'm like, "What does this even mean?" So I'm sitting here searching for these search terms, pulling up the handbook and like, "Oh, here's something that can explain it," sort of, but little by little I have come to an understanding about what each of these things are, because no one really ... There was no one that I could just ask and say, "What does this mean?"

Judy Schmidt: ESA, they got Zolt Levay to do a tutorial on how he processes it, and I have built upon that tutorial ever since. So Zolt Levay, is my ... I can't say he's my mentor because it was just one tutorial, but I really looked up to him, and I used his work as a goal, like I need to be as good as Zolt, I guess, that's what I did. I kind of studied his work. Anytime they would post a new image, I would look at it and say, "Well, how can I get my work to look like his work?" When I was doing images that he hadn't worked on then I could use what I'd learned from that on any image, so that's sort of how I taught myself.

Mat Kaplan: I'm fascinated by that fact that you basically are self-taught. I mean, I wish that you had crossed paths with my dear old friend, and former colleague Emily Lakdawalla, who picked it up, kind of I think the same way that you did, but you do cross paths now and then, right?

Judy Schmidt: Yes, I've learned a few things from her too.

Mat Kaplan: Emily has, I will mention, still has a course, a basic course in digital imaging that's available at planetary.org. You can find that, and we'll link to that as well, so that you can get a little bit more guidance than Judy, you had to work with, when she was starting out. There is a community of image processors, isn't there? Do you share information?

Judy Schmidt: Yeah. I mean, anytime someone asks me a question, either on Twitter or through the Flickr messaging system, or every now and then someone hunts down my email, I made it ... it's kind of purposefully difficult to find my email address.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, that's one thing we will not provide on the show page.

Judy Schmidt: I answer any questions, and I try to help anyone who wants to get into it. A lot of people do it, and they do it for just a little bit and they're satisfied with that short amount of time that they learned to do it, or life just happens and they don't have enough time, because it is a very time-consuming hobby.

Mat Kaplan: Another friend, Elizabeth Howell, a few days ago published in on space.com a nice interview with you, the article was called Here's How To Edit James Webb Space Telescope Images. You talked about some of your techniques there as well, it seemed like some pretty good guidelines.

Judy Schmidt: I've done a number of interviews over the past couple of weeks, really surprised at how many people wanted to do interviews, and it's actually hard for me to remember which, but I think she was the one I ... was a lot more detailed, and she wanted to know everything, and I tried to explain it as concisely as I could, but I haven't had a chance to read the article either.

Mat Kaplan: She and you did a good job with it, I thought, and she's great.

Judy Schmidt: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Well, she's a great science writer, and a good scientist as well, so I mean I wasn't surprised. Has it gotten easier to find the images that you base your work on? I know about some of these places where you can find them. In fact, one, the Astrophysics Source Code Library that was founded in 1999 at Michigan Tech, it has other partners now like NASA, you're listed there as the designer and developer, but is that someplace you rely on, or do I misunderstand this?

Judy Schmidt: Oh, no, that's a different ... that's for astronomy source code that, I mean, a few of them might be for image processing, but Alice was using a forum as sort of repository for these codes, and she didn't have a single place for it. Oh, my gosh, one night I was just like, "You need a real website." I guess, it took me a couple days, but I put together her website for her, and copied all of the forum posts, and turned them into actual database entries.

Mat Kaplan: This is source code more for working astronomers, amateur professional astronomers.

Judy Schmidt: Right. Right.

Mat Kaplan: I may have been in the Elizabeth Howell's interview with you, but you talked about the MAST archives, the one named after Barbara A. Mikulski, the former senator for Maryland, who made sure that we got the JWST eventually.

Judy Schmidt: Right, And Hubble, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, and Hubble, that's right. Yeah, she was always sticking up for-

Judy Schmidt: Probably other things.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, Johns Hopkins, and Goddard, and probably single-handedly. I hope to get her on the show someday. She has said that she'd be interested maybe at the end of this year or early next year, if it's not me, maybe somebody else would be talking to her on Planetary Radio, but tell me about this archive and how you make use of it.

Judy Schmidt: Right, that's my go to. It used to be the HLA, which is the Hubble Legacy Archive, but that one is not quite up to date. It's really good, but it's a great place to go if you're just starting out, because MAST is a lot more, there's more detail to it and there are more missions, whereas the HLA is just Hubble. But if you need JWST data, you're going to go to MAST, and man, I can't even imagine if I was just starting out and didn't know anything. It can be easy if you say you just want to search for any random NGC galaxy, you just type it in, and it will show you all the observations for that particular spot in the sky. I think a lot of people, especially a backyard astronomer, are going to try searching for a messier object first, and most of those are really ... they're big for a space telescope, so they're surprised, I guess, when they see the results, and it's like, "Oh, I can't see a whole galaxy. I just see basically one little tiny spot in that galaxy."

Mat Kaplan: There's a downside even to that now and then.

Judy Schmidt: You want to get a whole portrait of a galaxy usually, but it's great seeing closeups too. I think it's just surprising to people, maybe at first when they learn to switch from backyard mode to, "Oh, now we're working with the big telescopes." It's a different mindset, I think. You can really get some exploration done when you've got such a big telescope because even though other people have studied it, you haven't personally studied it so you can learn a lot of new things like, "Oh, wow, I didn't know that was going to look like that," like the Wolf-Rayet 140 picture.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, I was going to bring up the WR 140 binary star in Cygnus that has these gorgeous concentric rings that are emanating from its core. We'll try to put that one on the show page, so people can see what I'm talking about because I can't possibly do it justice, but what were you going to say about it?

Judy Schmidt: It's not aliens.

Mat Kaplan: Well, all right. We don't absolutely know that, but no, of course.

Judy Schmidt: It's not fake, and it's not a problem with the telescope, if it was a problem with the telescope, it would be in the news, just like the Hubble Blunder, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Judy Schmidt: It's a real thing. It's still generating mentions on my Twitter account, I keep reading. Every new person that sees it has their own idea of what it could be, and almost all of them are wrong. It's really funny. I mean, it's pulling all the ... how do you call them?

Mat Kaplan: The crazies.

Judy Schmidt: The crazies out of the woodwork.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, they're out there.

Judy Schmidt: Very imaginative.

Mat Kaplan: Yes, and it can be entertaining sometimes when it's not simply irritating.

Judy Schmidt: As long as they're not in my face angrily saying it's fake, then I'm fine, I'm just like ... Some of them, I reply to, but most of them I'm just like, "You do you."

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, I have the same philosophy, and I was afraid that you would say some of them angrily contact you, saying that you're part of the grand conspiracy that's hiding the inner meeting of those concentric rings.

Judy Schmidt: No, very, very few replies are flat-earthers, or people who think that everything NASA puts out is fake, the ones that do, I simply mute them, if they're particularly bad, I will block them, but I can't let them take space in my head.

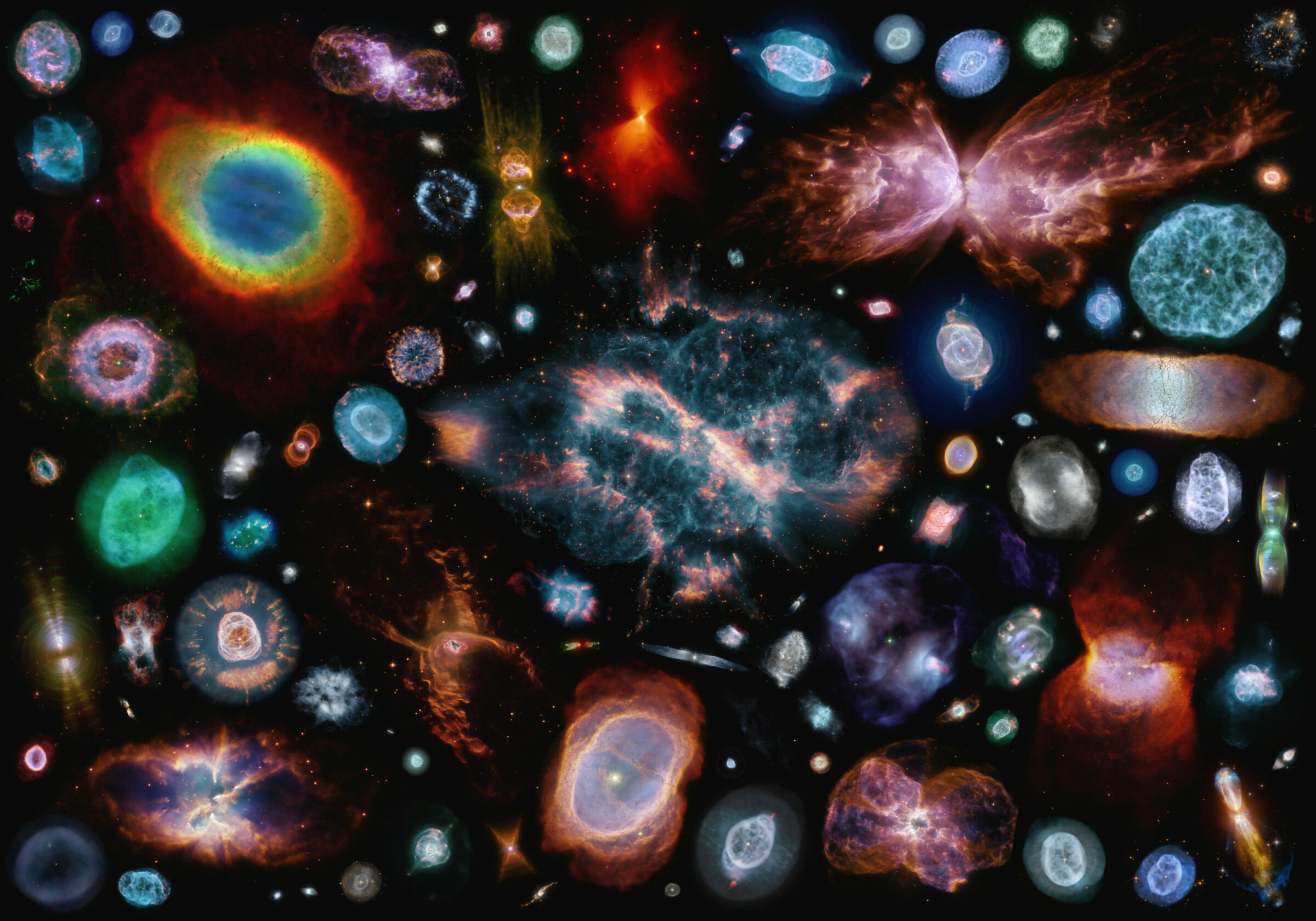

Mat Kaplan: I compliment you on that. We deal with them now and then, but our audience is generally pretty well-grounded, and just loves these for the beauty that they represent in the real universe. Let me ask you about another one since we're on the topic. Just terrific image reminded me of some of the stuff that Emily used to do, still does within the solar system, showing different objects in their actual relative size to one another. The image of a hundred planetary nebulae, and then you said, "How many can you name?" It's pretty gorgeous as well.

Judy Schmidt: Oh, gosh, that was a while ago, and I probably couldn't name very many of them.

Mat Kaplan: Don't worry, I couldn't get more than two or three. It's beautiful. I mean, what made you think, "Hey, nobody's ever put all of these together in one image in the right scale so that they're all in the same scale." I just thought it was a fascinating approach.

Judy Schmidt: It was one of those things where I was like, "Wow, these things are so amazing, and I need to process all of them." It was like catching Pokemon or something.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Judy Schmidt: I was searching through the archive and trying to find all of them, and later on I found out I did not get all of them, but it's close enough, but it's really hard to find them all. Then after I had processed I'm like, "You know, I wonder which one of these are really like," I wanted to see them next to each other, and I started putting that collage together, and that's where it ended up.

Mat Kaplan: It's a real collection of beauty, that one. Here's another, the Helix Nebula in infrared. I'm going to guess that Peter Jackson is sad that this image wasn't around when he was making The Lord of the Rings so that he could base the Eye of Sauron on it. It's pretty spooky and beautiful.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, that's what people like to call it. There's a few Eye of Sauron images. There's another Wolf-Rayet Star that people like to call the Eye of Sauron, that came from the Spitzer Space Telescope. I can't remember if I use WISE too, but yes, that was pre-JWST. It'd be awesome if JWST could look at that, although I don't know, you might have to mosaic, it's kind of a big picture.

Mat Kaplan: That brings up an interesting point, that some of your images are composites that are drawn from different sources, and of course we've talked about this on Planetary Radio, because now we're seeing stuff that's combined from Hubble, or maybe now JWST with X-ray images, and ultraviolet. Is that useful? Is that something that happens a lot?

Judy Schmidt: Sometimes it's useful, but other times not, like WISE and Spitzer work very well together because the relative resolution between the two is not too far apart. Spitzer is obviously much finer detail than WISE, but they're close enough that I can put them together and create a nice color image. The reason that happened was because I found that Spitzer does sort of something in between that I can put in the green channel. The green channel, I call it the most important channel because that's where your eyes are most sensitive, and that's where I want the nicest data to go.

Judy Schmidt: So, I put the Spitzer data in the green channel, and I can't quite remember where I put the WISE data, it probably goes in the blue, and maybe the red, but you've seen WISE images alone, they look incredibly colorful, the stars are completely separated from the nebulosity. In order to bring those together, you need another data set that sort of merges the stars. You can make a two-color image too, I've done those, and those come out pretty well, but I love to have a three-color image to generate that color dimensionality. It just adds so much to it, to not be two-colors or monochrome, so I started looking for things that both ... Well, obviously WISE did, I guess, almost the entire sky. I think there may have been a few things it couldn't reach or I don't ... anyway, I digress.

Mat Kaplan: WISE, which has now become NEOWISE.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Amy Mainzer, at the University of Arizona had been a guest of ours many times on the show, are now looking for near-Earth objects, and having some good success, and its previous incarnation doing all that great work across the universe.

Judy Schmidt: Right. There's actually ... I think there's still a lot that could be done with those, and it's just a matter of looking at Spitzer's archive and saying, "Oh, this is a really good image. Nobody's done it before," and then pulling the WISE data over and combining them together. I just don't have time to do everything, especially now that I have a kid, he's out there, I'm just waiting for him to start knocking on the door.

Mat Kaplan: Start complaining? Oh, we better move along then, because I know how that can be. I'm amazed-

Judy Schmidt: Well, he can't talk yet.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, okay. Well, even [inaudible 00:44:39] can be even more demanding. Congratulations, by the way, on that production well.

Judy Schmidt: Yes, thank you.

Mat Kaplan: I'm also remembering how many times I've talked to scientists, like Cassini scientists who have their morning meeting, and the first thing that they do is look at an image from some amateur, so-called amateur image processor like you, and marvel at it because it's not something that they ever were going to have time to work on. So the degree to which they rely on work from you, and people like you, really there's a seemingly endless list of organizations, news sites, YouTubers, other image processors, and like I said, the just plain space geeks like me who share your work. Even though I know a lot of scientists have deep appreciation for your work, you sometimes are concerned about, I think you put it as whether you might be stepping on the feet or the toes of some of these teams that are working with these great space telescopes. Do you feel that way?

Judy Schmidt: Sometimes I worry about it. I'm not seeking to take recognition, and sort of scoop their releases, but I just get excited about it. I do sometimes get contacted by astronomers who are like, "Hey, hold off, don't post this to Twitter quite yet. Let's try to do something so that we're more coordinated." But with these larger institutions, I know they have a whole team they're working with, and they can't just put an image out instantly. They're trying to organize it and get everything, I guess, so they don't get these random questions like, "What is this?" They want to have it all upfront and explain it and say, "We know what this is mostly," sort of, I mean, not everything is known, otherwise why would we have space telescopes? So, yeah, I don't want to be like, "Oh, I'm better than these people." I know I'm not, and absolutely, I feel like a lot of the image, especially, say the two-color Jupiter image was fairly simple to put together. I think that would've existed without me, for sure. They would've come up with that on their own, the three color image, maybe not.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, I wonder if they would've, because they're awfully busy people.

Judy Schmidt: Right.

Mat Kaplan: I think that on balance, what you bring to this, and what you add to bring to their work, I think it's vastly appreciated. I think the appreciation for it vastly outweighs any feelings of, "Oh, yeah, we were going to do that."

Judy Schmidt: Sometimes I try not to, if they're going to post, say this recent image of the Tarantula Nebula, there's a chance that I won't even do that because they've already done it so well, nobody needs me to come in and be like, "Look at what I can do." Every now and then there's things that I just have a personal interest in, and there's sort of a lull in activity, and I'll go back to one of the big image releases and process it, but I'm not trying to create conflict or scoop them, so to say.

Mat Kaplan: My guess is that most people understand that you, and people like you do this out of your love for it, and wanting to share what our boss, Bill Nye, calls the passion, beauty and joy, the P, B, and J.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, P, B, and J, that's funny. I named my kid Benedict so that we could be Pat, Benedict, and Judy, so it's P, B, and J.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, that's great.

Judy Schmidt: It's just a silly thing.

Mat Kaplan: I love that. I'm going to tell Bill about that, more P, B, and J. This takes so much time, and so much work, why do you do this? What do you get out of it?

Judy Schmidt: Like I said earlier, it's a way of exploring the universe, like Wolf-Rayet 140, that excited me, that's why I ended up posting it to Twitter with this regrettable description. I feel like it was partly my fault for opening the can of worms and saying, "I don't know what this is," because that really opened people up to saying, giving their own ideas and saying, "Well, I think it could be this," or, "Are you sure this is a real thing?"

Mat Kaplan: I saw that.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, but somebody at signed me, how can we say? On Twitter, and they were like, "Have you seen this? Do you know what this is?" I was like, "Whoa, what the heck is that? I missed it." I was like, "How could I miss this?" Because it was already a month old, and other people had processed it and posted it on Wikipedia, and I was like, "What? No, I have to do it." So-

Mat Kaplan: I saw other people's work, and I have to say I thought yours took the cake, it is a gorgeous image. Go ahead. Sorry.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, I was just going to continue on about how it's a way for me to explore, that's what I personally get out of it. It's also kind of meditative for me to put these different data sets together and puzzle them out. It's like if you had a jigsaw puzzle, and you're just trying to put it together, it's sort of a meditative thing, if you like puzzles. It gives me something to focus on. I love sharing it with people too, and that's the third thing that I get out of it, I love to let people join me on this trip, this cosmic trip.

Mat Kaplan: That's a great way to describe it. I love that. Let me ask you about one other image, and it's the one that Elizabeth Howell kind of focused on when she talked to you for space.com. It is just gorgeous. I can lose myself in it. It's M74, The Phantom Galaxy.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, that one was so far the most, I feel like the most impressive galaxy out of that PHANGS data set. Their whole program is amazing, they've got so many beautiful galaxies in the Hubble data set already, and now they're adding these JWST images to that already a gorgeous set. It's just one after another a beautiful galaxy, and they're all different, they'll have different reasons for looking at this particular galaxy. That particular one is just like, "Wow," and I think they thought that another one of them, I can't remember the number because I'm terrible at remembering the numbers, but the one with the very thick dust bars, they were-

Mat Kaplan: I'm not going to be able to help you. I can't keep [inaudible 00:51:24].

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, I know, I know. I can look it up real quick.

Mat Kaplan: Don't worry about it.

Judy Schmidt: I mean, they were like, "Why aren't these dust bars showing up?" I think the thing is, it's not that they don't show up, they show up great, it's just that all the other dust also shows up. So, all of a sudden these back lit dust lanes that were very prominent in the visible spectrum, suddenly they're just as prominent as every other bit of dust, so it's like ... they sort of just blend it in, and it was like, "Oh, hmm." Well, it's still a good-looking galaxy, it's just a little underwhelming, I guess, they were hoping for another thing like the Phantom Galaxy, I guess.

Mat Kaplan: Do you have advice for anyone who might be listening to this, and looking at your work, and would be intrigued, and might want to follow in your footsteps, join this community of image processors?

Judy Schmidt: Don't give up, I guess. It's not going to be something that you get good at overnight. It took, I think at least four to six months for me to really feel like I was comfortable with, and I was processing nonstop. That was when I really had nothing else to do with my time, I didn't have a kid. I didn't even have a cat, and Pat was at work all day, Pat, my spouse. Even just full-time going at it as much as I could stand, still I was just taking in all this information, and after that amount of time, and I'm still learning new techniques, and coming up with new ways to sort of solve the puzzle. Gosh, even after using Photoshop itself for over 20 years, I'm learning things about Photoshop too, there's a lot.

Judy Schmidt: Astronomy itself has a lot of different subspecialties from specialty to specialty, even other astronomers have a hard time, if they're specialized in one thing like galaxies, they're not necessarily going to know a lot about planets. The astronomy itself sounds like, "Oh, you have just an astronomer that they study everything," but no, there's people who study just active galactic nucleus, like the black holes, people who study stars, and not just one segment of star, it could be star formation versus the end of ... I don't like to say that stars die, because they're still there even after they stop fusing.

Mat Kaplan: That's true.

Judy Schmidt: Energy source, [inaudible 00:53:59] they just a ...

Mat Kaplan: I like that.

Judy Schmidt: I don't know why, I don't like saying that stars die. I've always taken an issue with that, for lack of a better word right now.

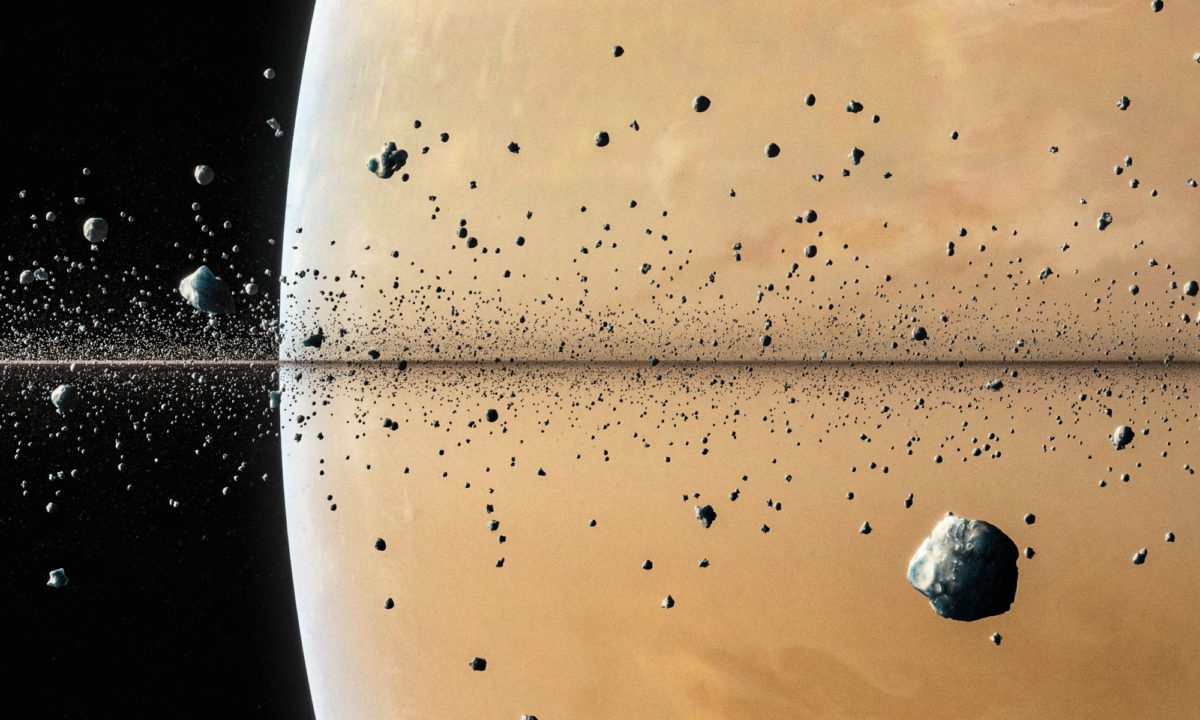

Mat Kaplan: I like your approach to that. I think I'm going to try and change my reference to dying stars from here on out. So you've had even more influence, and this time it wasn't even directly related to an image. Your work, well, maybe your best known for the image processing work, but you are also an artist of original work. I'm thinking in particular in this case of this absolutely beautiful image of Saturn and its rings, and you can see the individual ring particles. I've seen that image for a long time in many places, and did not know until a couple of days ago that that was something that you had put together. Very, very nice work, and then I read your description of it, and it looked like you are hoping that you got this right, but we don't really know yet.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, I'm surprised that you've seen it in so many different places. I didn't think it was very widespread. There were other images that I felt like maybe did it better than I did.

Mat Kaplan: It's just beautiful. It's really, I'll use the word again, it's breathtaking, and we'll put that one on the page as well. Judy, you've been very generous with your time, and certainly with your skills, your talents, thank you for all of this gorgeous work. I look forward to seeing much more of it. I'm stealing this from you since it's your motto on Twitter, may all your guide stars be acquired, Judy, and also, ad astra, to the star.

Judy Schmidt: Yeah, those guide stars, sometimes they are not acquired, and it's a very sad day when you get your billion dollar telescope data back, and it's just a streak. Oh, man, that's got to be heartbreaking.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to stretch the metaphor here and say, I think that your images are providing guide stars for a lot of people as they become more interested in the wonders of the cosmos. So again, thank you for this great work, and thank you for taking some time with us today.

Judy Schmidt: You're welcome, and thank you for inviting me.

Mat Kaplan: Artist and astronomical image processor extraordinaire, Judy Schmidt. We've put some of her work that we talked about on this week's show page at planetary.org/radio, along with links to her Flickr collection, and much more. It's time for What's Up? on Planetary Radio. Here is the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, Dr. Bruce Betts, who is very glad, I'm sure, to be talking with me virtually this time. Welcome.

Bruce Betts: I am indeed, but I've looked it up, and apparently I can only catch computer viruses by doing this.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad. I'm glad.

Bruce Betts: But I'm so sorry you've got COVID, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Bruce Betts: I feel badly for you. I do want to, at the risk of changing my behavior entirely, compliment you. First, let's compliment me, I've been on every show that we've ever done in 20 years.

Mat Kaplan: Yes.

Bruce Betts: Mat has never missed a show. I twisted his arm like a decade ago when he ran mostly repeat a couple times, it doesn't matter, come rain, shine, COVID, he not only records the show, he produces it, he edits it, and he makes it the glorious piece of art that it is. Even while sitting there with some nose thing that makes him more ridiculous, but helps him breathe. We appreciate it. I can't believe you do this, and I've done this, and I'm in awe.

Mat Kaplan: Hey, the brief write is because I'm going out for the Minnesota Vikings. It has nothing to do with COVID.

Bruce Betts: What? Oh, God, they're having enough problems. They're doing okay.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, I appreciate all of that. Yeah, you're right, every single show, even the ones with repeated features, and those have been few and far between, has had new content, especially a brand new What's Up? Because after all the night sky changes every week.

Bruce Betts: It waits for no one, so let's talk about the night sky, and the evening sky when the sun sets. If you look over in the East, you'll see really bright Jupiter looking lovely, and if you look up above it aways, you'll see yellowish Saturn looking lovely. If you wait two, three, fours hours until the late evening, you'll see Mars come up, and Mars getting brighter and brighter as we get closer in our orbits. It's hanging out near Aldebaran, the bright reddish star and Taurus, but it puts Aldebaran to shame right at the moment because of its glorious brightness. You might be able to check out Mercury, not quite yet, but in a few days in the pre dawn sky, low in the East. On due this week in space history, nothing. Well, there were a couple things this week, insignificant things. 1957, October 4th, what is that? Sputnik.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Bruce Betts: Sputnik was launched, yeah. So first spacecraft, and then NASA was started a year later, October 1st, the official beginning of NASA.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, no coincidence there by the way.

Bruce Betts: No. We move on to Random Space Facts.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, that sounds so good with the reverb.

Bruce Betts: Oh, nice. How far away is Voyager 1? Well, I'm glad you asked. As of September, 2022, so now as we record this, in the amount of time it takes to send a radio signal at the speed of light to Voyager 1, and have it return a signal back at the speed of light, you could drive from LA to Boston with almost two hours to spare.

Mat Kaplan: Wow.

Bruce Betts: This random space fact assumes a straight path with no breaks at a 100 kilometers per hour.

Mat Kaplan: All right. Yeah, I guess you'd still be within the speed limit. No stops for gas or potty breaks?

Bruce Betts: No, I'm a planetary scientists, I simplify things. We approximate, but still come up with about the right answer.

Mat Kaplan: That is a great random space fact. Thank you.

Bruce Betts: You're welcome. We move on to the trivia question. I asked you approximately, so you know, kind of close, how long from launch will it take Korea's Danuri mission to reach the moon? It's on its way right as we speak, and how did we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: We got a nice response. Thank you everybody. Here is the answer, I think, from Dave Fairchild in Kansas, the poet laureate of Planetary Radio. Danuri means enjoy the moon, so can you give an answer to why it's headed toward the sun? Ballistic lunar transfer, it's heading out to point L1, Lagrangian, remember? And should be captured by the moon around 16, December. Actually, he did provide the number of days as well, but I'm going to look to our, I think our winner, first time winner, long-time listener, William Noack, who says, "It's about 19 weeks and a day, August 4 to December 16," which is, and there's some question about this, some people said 134 days, which is what this would be, some said 135. Is this close enough?

Bruce Betts: That is close enough. That is accurate as I could find it online, and there may be a little fudge, but yeah, a 134, 135 days to get to the moon. We get to the moon indeed, oddly, they travel to not the Earth-Moon L1 Lagrange point, which my brain might have understood, but the Earth-Sun L1 Lagrange gravitational balance point. Because then, they go out there, they do it just right, they actually can use less fuel by hitting that gravitational balance point, and then doing their thing, and kind of cruising in orbit, anyway, they get there ... they'll get there. We're looking forward to it. Just impressive. Certainly competing for one of the longest trips to the moon ever, but very cool. Congratulations to the Danuri team for a successful mission so far.

Mat Kaplan: Congratulations, William, up there in beautiful, on the beautiful central California coast. You are going to receive that brand new, and stunning JWST T-shirt from our friends at chopshopstore.com, that's all one word, by the way. It's where you will also find the Planetary Radio T-shirt, which I'm kind of biased, I'd say it's as beautiful. In fact, all of The Planetary Society merch is there at chopshopstore.com. I have more, of course, from Norman Kissoon in the UK, "Danuri is a portmanteau of two Korean words, dai which means moon, and nurida which means enjoy. According to the Ministry, this new name implies a big hope and desire for the success of South Korea's first moon mission." Well done.

Bruce Betts: Do you know what a portmanteau of our names is, Mat? Brat.

Mat Kaplan: Brat, how appropriate?

Bruce Betts: How appropriate.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, we should have discovered that years ago. Carlos Tello in Germany, he was in South Korea a couple of years ago, "What a nice and exciting country and culture," he says, "I especially enjoyed the volcanic island of Jeju in the South. That island has a very nice role in the Korean Dramedy Extraordinary Attorney woo, that my wife and I have been enjoying. It's an excellent show. I recommend it very highly. It's a beautiful island too." Mel Powell says, "It's also close to the time that it would take for him to drive from his San Fernando Valley home to Planetary Society headquarters in LA's [inaudible 01:04:35].

Bruce Betts: Well, yeah, at least during traffic time.

Mat Kaplan: Ben Owens in Australia, "9.6 lunar days," he's right, I checked, "are about as long as an average Australian household takes to consume a small jar of Vegemite," which is interesting. I thought Australians would go through that more quickly, a small jar of Vegemite would last the typical American family basically forever, because we would never eat it.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, until the estate sale.

Mat Kaplan: [Inaudible 01:05:07] in Arizona, "If you drive around 75 miles per hour on a direct path, you will get to the moon in 135 days, no stopping for gas." Remarkable, huh? He had no idea what your random space fact would be.

Bruce Betts: I had no idea what his answer would be, so yes, we're just great minds thinking alike.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. Joe [inaudible 01:05:29] in New Jersey, "I recommend that the shadow cam, that's the camera that Danuri is carrying, be nicknamed Lamont Cranston." Do you get it? "Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?"

Bruce Betts: The shadow knows. I forgot the shadow, that was the shadow's name?

Mat Kaplan: That's right.

Bruce Betts: I remember that beginning to the radio show, but okay. Wow. Sure, we'll suggest it.

Mat Kaplan: Daniel Sorkin in New York closes us out with, "Go Danuri, and congratulations to our friends in South Korea on this mission."

Bruce Betts: That's good. Good stuff. Did you want some good stuff for next time?

Mat Kaplan: Please? Why break the habit now?

Bruce Betts: So, hey, did you see that spacecraft impact the asteroid?

Mat Kaplan: I did catch that.

Bruce Betts: There's an interesting history of the getting to that point. One of the pieces, of many pieces, was there was an ESA, European Space Agency studied mission, just studied, called Don Quixote, which never went beyond a study, but was one of the many pieces that led to DART and Hera. So here's your question, what were the two spacecraft to be named, that were to be part of the Don Quixote mission had it existed? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: I have a guess, which I would not be a bit surprised to learn is accurate, but I guess I'll just have to wait to find out. You have until the fifth, that'd be October 5th at 8:00 AM Pacific Time, to get your answer in. What else could we give away this week, except a Planetary Society Kick Asteroid rubber asteroid?

Bruce Betts: Cool. You know what would also be great?

Mat Kaplan: What?

Bruce Betts: Use Mat Kaplan Breathe Right Strips.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know. There's been a lot of talk about cloning me, and so I think it'd be a mistake to hand somebody a used Breathe Right Strip. It probably wouldn't go well.

Bruce Betts: That's terrifying. Okay, are we done?

Mat Kaplan: We're done.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there. Look up the night sky, and think about Mat Kaplan getting really healthy. Thank you, and goodnight.

Mat Kaplan: It is devoutly to be wished, I appreciate that. It comes from the Chief Scientist of Planetary Society, Bruce Betts, who joins us every week here for What's Up? Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its often astonished members. You can start sharing their experience at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Ray Paoletta are our associate producers. Josh Doyle, composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth