Planetary Radio • Nov 11, 2020

A Rogue World Wanders as PlanetVac Heads for the Moon and Mars

On This Episode

Radek Poleski

Astronomer for Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw

Bill Nye

Chief Executive Officer for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Kris Zacny

Vice President and Director of Exploration Technology for Honeybee Robotics

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

In a busy episode, we’ll talk to a discoverer of a distant, lonely planet that wanders the galaxy, and then turn to plans to send a radically-simple sample collection system to the Moon and Mars’ moon Phobos. Planetary Society CEO Bill Nye will add his congratulations for the PlanetVac team. We’ve also got a signed copy of Bill’s latest book for the winner of the new What’s Up space trivia contest.

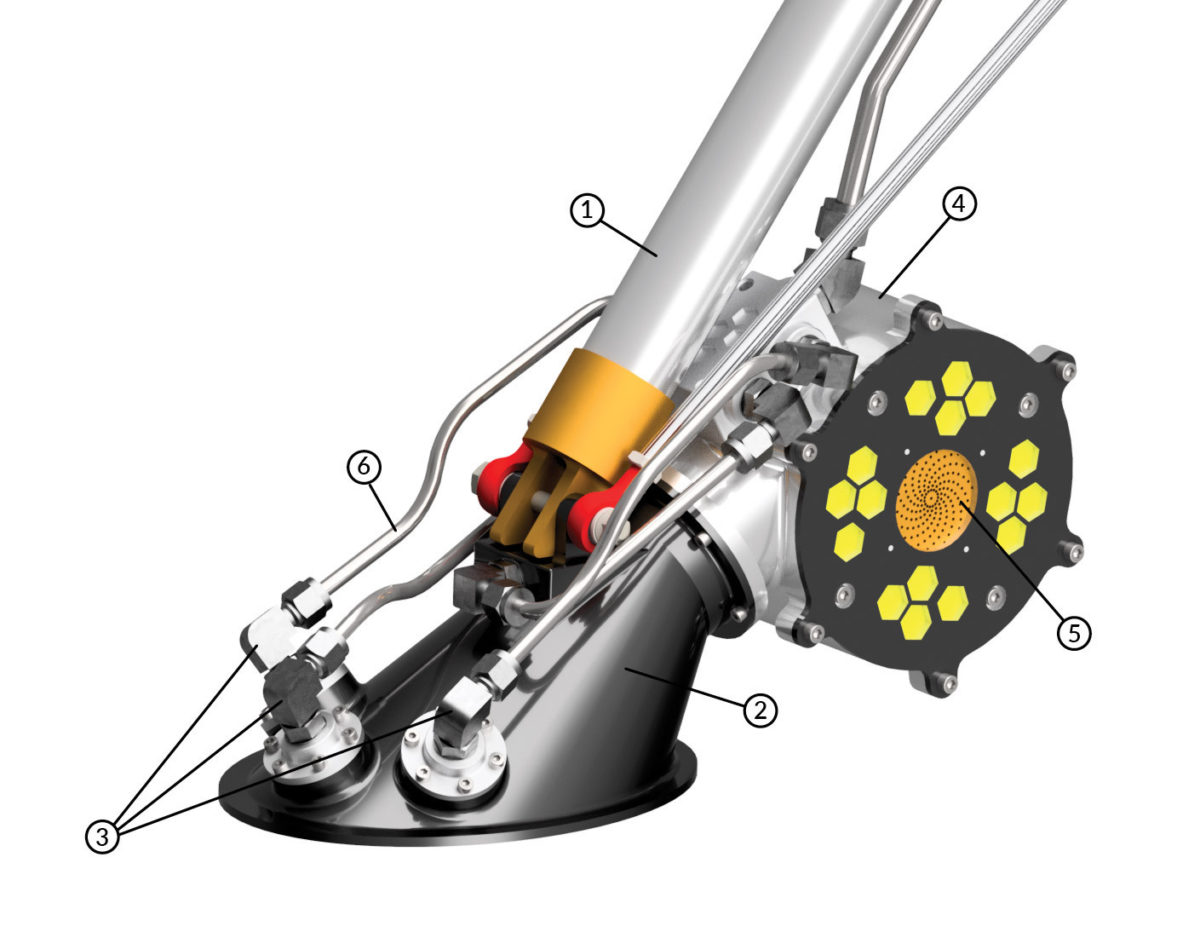

PlanetVac Testing on Xodiac Rocket In 2018, Planetary Society members and supporters helped fund a test of the PlanetVac sample collection technology aboard a rocket called Xodiac. Xodiac, built by Masten Space Systems, takes off and lands vertically in California's Mojave Desert, allowing hardware developers to simulate the stresses of a rocket launch and landing. PlanetVac was attached to the rocket’s leg and successfully collected 332 grams of simulated Martian soil.

Related Links

- An Earth-sized rogue planet discovered in the Milky Way

- Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw, founded in 1825

- The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE)

- PlanetVac: Sampling Other Worlds

- NASA and JAXA to Send Planetary Society-supported Sample Technology to the Moon and Phobos

- Honeybee Robotics

- NASA Commercial Lunar Payload Services

- Your guide to MMX, Japan’s Martian Moons eXploration mission

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prizes:

A signed copy of Bill Nye’s Great Big World of Science by Bill Nye and Gregory Mone.

This week's question:

Who gave the names to most of the lunar maria that are used today--those approved by the International Astronomical Union?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, November 18th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

How many of the largest dwarf planet Pluto would fit inside the smallest planet, Mercury? Just a basic volume-to-volume comparison, please.

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the 28 October space trivia contest:

As measured by either volume or average diameter, what is the smallest asteroid that has been visited by a spacecraft?

Answer:

As measured by volume or average diameter, the smallest asteroid that has so far been visited by a spacecraft is Itokawa.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: A distant world wanders the galaxy and PlanetVac heads into space this week on Planetary Radio. Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan at the planetary society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. So much to share with you today. We'll talk with astronomer Radek Poleski whose team has used relativity to discover an earth-sized planet that is nearly a quarter of the way across the Milky way. Then we'll turn to Kris Zacny of Honeybee Robotics along with our own Bruce Betts to learn how the radically simple gas driven sample collection system called PlanetVac will soon head for the moon and Mars. Planetary Society CEO, Bill Nye will share some thoughts too and it's a signed copy of Bill's newest book that someone will soon win in the Whats Up! space trivia contest. Bruce will announce that Pale Blue Dot where we all live tops the November 6th edition of the down link.

Mat Kaplan: You'll find these stories among others below it beginning with word that there may be as many as 300 million habitable planets in our own galaxy alone. We've also learned that the European Space Agency's little Philae Lander carried to comet 67/P by Rosetta tumbled through ancient surface ice that was and I'm quoting "fluffier than cappuccino froth." And if you want to see how our solar system's biggest worlds may have migrated outward from much closer to the sun. Well, we've got the video at planetary.org/down link. Here's something that is not in the down link. It's my personal thanks to those of you who took a few moments to leave us ratings and reviews in Apple podcasts across the last few days, I'm still hoping more if you will join them. I learned a remarkable thing a couple of weeks ago, an international team led from the university of Warsaw in Poland announced that it had discovered an exoplanet.

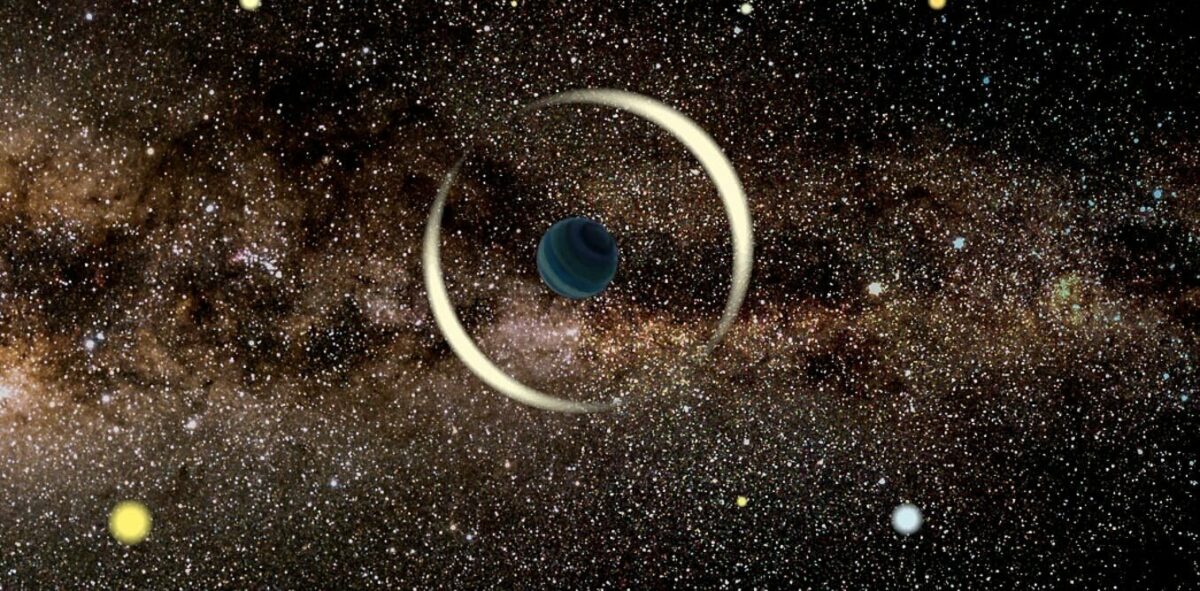

Mat Kaplan: Did I hear you say, "so what?" Or maybe you agree with me that the discovery of any world is worthy of celebration. But this one is wandering the galaxy on its own tens of thousands of light years from earth. And we can once again thank Albert Einstein's insights for enabling its discovery. Astronomer Radek Poleski is one of the leaders of that team. He joined me from Warsaw a few days ago. Dr. Polaski welcome to Planetary Radio and congratulations on this nearly miraculous discovery of this little world that is off floating across the Milky Way all by itself. We're glad to have you on with us on Planetary Radio.

Radek Poleski: Good afternoon.

Mat Kaplan: Before we talk about how you and this team made this amazing discovery. I'd like to hear more about this lonely little world. What can you tell us about it?

Radek Poleski: Yeah. So you said the most important part, meaning it's lonely. So we found a planet that seems to be just a single planet that is not orbiting any star. Like earth orbits the sun, this little planet seems to have no star around it. So it's just a single planet. There's nothing more really.

Mat Kaplan: I have read that our current understanding of planet formation and what happens in solar systems indicates that this single example may be just one of what millions across our galaxy?

Radek Poleski: I'm pretty sure there are more such planets in the galaxy. It's very hard to find them. So we found one that has very small mass and I'm almost sure there are planets with smaller masses. We have just a few such objects that we currently know. And we know that it's very hard to discover them. So their real number must be much, much higher.

Mat Kaplan: Do we know how far away this world is?

Radek Poleski: We know it's closer than the galactic bulge that's for sure because we detected the planet in a very rare phenomenon that is called gravitational micro lensing. And micro lensing happens when the light of the background more distant source of light travels next to a massive object in this case a planet and the gravity of the planet bends at the light rays. The effect of that is that we receive more light from the source. And in this case, as this casing for most of the micro lensing events, the source is in the galactic bulge. So eight and a half kilo parsecs from us 25 something thousand light years from us. And for sure we know that the lens meaning the planet that we found is closer to us. Most probably it's around 6,000 parsecs away.

Mat Kaplan: And what would that be in light years? Do you know offhand?

Radek Poleski: Around 20 thousands.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely amazing to think that not only has this world which I've read is maybe just the size of our own of earth could be found at that kind of distance. And we'll talk more about gravitational lensing in a moment. So when you say on this side of the galactic bulge, that's largely because it's so difficult to see through that bulge, which is basically the core of our galaxy. Is that correct?

Radek Poleski: Micro lensing is very, very phenomenance because we need a source in the lens and us as an observer to be aligned almost exactly at one straight line. So if you observe a million stars for a year, then most probably you will see only a single case of micro lensing. So we observed galactic bulge because that's the place on the sky where we can see lots of stars. And then we see the micro lensing events where the sources are the stars in the galactic bulge and the lenses can be either in the galactic bulge or in the galactic discs slightly closer.

Mat Kaplan: I see, before we leave this world I have to ask, is it crazy to talk about whether a rogue planet like this could be habitable? Yes, that does sound like a crazy question, but then I think of some place like the moon and sell it as it's Saturn, which has liquid water inside it. It was thought for years to be far too small for that it's fairly distant from Saturn. So it's not hugely influenced by Saturn's gravity as is a world like Europa or Jupiter. Do you think that this is even worth talking about whether it is a habitable world or is that a real possibility?

Radek Poleski: For sure it's worth talking about. It's I would say very important scientific question and it's important not only to scientists but for the society as a whole. The problem is that it's very hard to verify if there's any possibility of light on this planet or not. We don't know that much about the planet. What we can say though, is that there are two main mechanisms that could produce this object. So first of all, these objects could be formed in a similar way as stars form. Meaning a collapse of a single cloud of gas. It just happened that this one has smaller mass than the stars, very small amounts in this case.

Radek Poleski: So, that's one possibility. The other is that this planet was ejected from a planetary system that had more planets and these planets were orbiting star. In this case in this second scenario, it's possible that some forms of life started on the planet while it was orbiting its star. And then when the planet was ejected due to gravitational interactions between planets, then the life still survived for some time. It's hard to say much more than that. But for sure, we would like to know the answer to the questions you're posing.

Mat Kaplan: It is a stunning possibility. We have talked about gravitational lensing several times in the past on our show. Usually in terms of revealing giant structures like galaxies that formed very early in the history of the universe. I was very surprised to learn that it could work with something as small as a planet. And from what you have said, the gravitational lens in this case may have been another planet. Something no bigger or roughly in the same size range as the planet that has been revealed.

Radek Poleski: Yes. All the time I'm talking about gravitational micro lensing. And the micro lensing means that the additional images that are formed are so close to each other that we cannot separate them on images taken from the ground or from Hubble Space Telescope. We just see that we're receiving more flux from the source than we should have if there was no micro lensing. Such events happen in the galactic scales and that's why we observe the galactic bulge. Currently we detect more than 2000 micro lensing events per year. Small percentage of those shows not only does there's the main lensing object which is a star in most cases but also some of the shallow objects which in some cases happens to be a planet. In this case, we see extremely short micro lensing events. So this event...The timescale of the event was 42 minutes.

Mat Kaplan: Wow.

Radek Poleski: Yes. So it's something extremely short really. And over these 42 minutes, the whole event happened. If you compare that to the galaxy lensing about which we talked before, then these galactic lenses don't change. They slightly change over our lifetime but they're extremely similar from one eBook to another. Here we have something completely different and a completely different observing strategy. We don't need huge telescopes. We need moderate size telescopes but with large cameras with big field of view, so that we can see many stars a time. And then use that to study lots of stars. And from those stars to search for these very rare micro lensing events.

Mat Kaplan: And we will talk about a very wide field telescope that is hopefully going to be headed for space before too many more years pass, one that you are hoping to work with. But for now we'll stick with how it's being done from the surface of our planet. You talked about how rare it is to make this kind of discovery but I hope that you can tell us about the program that you and this team have been working with for 28 years now, which I see is O-G-L-E stands for the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment. What do you actually call it? Do you call it OGLE or OGLE?

Radek Poleski: Yes OGLE. That was the idea behind the acronym.

Mat Kaplan: I love it. Tell us about OGLE.

Radek Poleski: OGLE is a longterm photometric survey. It started in 1992 and the last components Observatory in Chile of the one meter telescope called Swope. Three years later, a separate telescope was built only for this project. It was called Warsaw telescope because the diameter of 1.3 meters. Every few years we are attaching a new, larger camera to the telescope. Currently the camera is so large that no larger camera can fit underneath the telescope. So we're using full capacity of the telescope. The product started to be small compared to what we're doing right now. Right now we're monitoring two billion stars regularly and we're observing the galactic bulge to search for micro lensing events and variable stars.

Radek Poleski: We're also observing commercial Lani clouds where we search for sulfates, or we did some other studies of the variable stars. We also observed the galactic disc fields a year ago. We've published a paper where we analyze the structure of the galaxy. Based on sulfates, we showed them that the galaxy is warped. So, that was quite well publicized result. We observed the star that's on which we seen the planetary signal. We observed the source star in this case for 23 years. So, since we built that... The second telescope was built, at that time I was not involved in astronomy at all, but the heads of the project and most importantly, professor Andrew Dulsky they built it and it's in operation since then. Currently, unfortunately it's not operating due to coronavirus pandemic, but we hope to return to observations as soon as possible.

Mat Kaplan: I read that and I'm sorry that observations had to end but of course the pandemic has gotten in the way of so much of human activity including science.

Radek Poleski: I would say the observations are paused not ended.

Mat Kaplan: Yes that's a much better way to put it. I am still blown away. When I hear an astronomer like yourself, say that you are monitoring 2 billion stars with one instrument. That must be quite a wide field.

Radek Poleski: Yes. The field of view of the camera is 1.4 square degrees. So it's more or less six times larger than the size of the full moon on the sky. And we take a single image of that size every two minutes in the galactic bulge. So we take quite a lot of data.

Mat Kaplan: I hope that listeners will go to our show page at planetary.org/radio for this week's episode because there we have links to the OGLE website and you'll be able to see simulations of what happens. It's actually quite fascinating to see what happens as this source that causes the Lensing crosses the path of what it's going to reveal. It is absolutely fascinating to see. What do you actually see? Is it an image or is it just a light curve?

Radek Poleski: Yeah. So the images we're taking they look very dense, meaning there are lots of sources of light. In fact, one on top of another. We can resolve the brighter ones, the very faint ones. We cannot in fact resolve there's one on top of another. What we've seen was slight brightening of one of the sources. So it didn't get bigger. It just got slightly brighter and slightly, I mean I think most of us would not be able to see a difference between the two images, even if we knew it was time to look at what objects and of course we don't know. So it's a really small amplitude short episode though in this case, I would say it's important to know that we're sure that even though it happened, it's not that we had maybe some problem with our camera or some other thing. And I know that because the same event was observed by a different collaboration and different telescope with a different camera. And that was one of the telescope belonging to Korea Micro lensing Telescope Network. And they've seen... Their data confirmed our findings. So what we see on images is just the brightening. Then we turn it to light curve as you said, meaning we have a graph which shows on the X axis time and on the Y axis brightness. And we've seen a signal we were looking for.

Mat Kaplan: Can you envision a day in which it would actually be possible to image a tiny object like this that is so far away?

Radek Poleski: Honestly not. I don't think in my lifetime we will be able to image such an object. We could image bigger objects that are closer and somehow similar, but really what we see is an effect of gravity of this object and has nothing to do with how bright it is. We only see gravitational signal of the object not its brightness. So it's unlikely we'll see any light from it in my lifetime.

Mat Kaplan: I'm afraid that does sound likely. But let's talk about the future. I mentioned that other space telescope now known as the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope formerly the WFIRST, you are looking forward to making observations with it?

Radek Poleski: Yes. Yes. That's extremely exciting possibility to have such a telescope. So it will be a telescope quite similar to the Hubble Space Telescope. But it would only observe in near infrared bends, though its camera would be hundred times larger than the Hubble telescope camera. It will have few different main programs. And one of them is to conduct a survey of the galactic bulge in order to search for planets via micro lensing. I'm sure that the survey will discover many other important things including an order of hundreds thousands traveling planets, but its main goal would be to search for planets using micro lensing. And it will overcome some of the problems that we have from the ground, which simply cannot be overcome just by having more telescopes and taking deeper exposures and so on. One of the important aspects of the Roman telescope is that it will be able to observe selected fields in the galactic bulge continuously. Every 15 minute we will have an image and on the ground you always depending on the weather, on moon maybe. You have a day when you cannot observe given the field and with Roman telescope who have deeper images. They'll be in unified bends, so it will be early and much deeper in fact hiding from the ground we're getting right now. And we will have lots of those. So we'll see thousands of micro lensing planets in this data for sure.

Mat Kaplan: That's very exciting to know that that is not far off in our future. I have to ask you about something that is much farther out if it ever happens. And I don't know that you've ever heard of this project, but it is one we've talked about on our show. The lead, the principal investigator is a gentleman at the jet propulsion lab named Salvatura Chef who's been my guest. He's working with my old boss Louis Dill Friedman, one of the founders of the Planetary Society. They are researching the possibility of sending a spacecraft and using our own sun to do gravitational micro lensing. And then this spacecraft would be able to move around so that different objects where we would be able to do the micro lensing with them. Is this something you've heard about and whether you have or not, what do you think of that kind of a mission?

Radek Poleski: No, I haven't heard of that one. It's the first time I hear about it. It's known that we can try to use objects at the distance seniority Kuiper Belt to observe micro lensing on them as lenses though it's hard for me to say if you're really able to point it to any specific source. Yeah. So if you have a space curve that you can control, yeah then that one gives maybe more possibilities than I've heard before using natural objects in the solar system. It sounds interesting for sure.

Mat Kaplan: I have just one other question for you and it's about the institution where you work. It would appear that the university of Warsaw has been at this work with OGLE and the gravitational micro lensing for many years. And that the university is a real leader in this field. How did you become involved?

Radek Poleski: Poland is my home country. So I was born in Poland and when I was choosing the university to which I'll go, somebody told me that Warsaw is the best place in Poland to study astronomy. And I think it was true. I did my Masters and PhD in Warsaw. During my master's studies I started to be involved in the OGLE project. When they started PhD, I was involved in observing. So I've been to Las Campanas Observatory many times. I've spent more than 500 nights on the mountain and the telescope altogether during my life. So it's quite a long time. I would say after doing PhD, I went to Higher State University where also the study of micro lensing phenomenon is very well established. And I met people who are more involved in analysis of the data and running other projects. So I got a good understanding of data analysis some aspect of data analysis there. I stayed there a few years and then I went back to Poland. So yes, I am involved in the OGLE project for 11 years now. So it's a big part of my life.

Mat Kaplan: That's a lot of time you've spent at the telescope site at Las Campanas. I've also been up high there in Northern Chile up in the Atacama. It's quite a beautiful place in its own way. Isn't it?

Radek Poleski: Yes it's beautiful. And it's beautiful for astronomers. So at the Las Campanas Observatory, the giant Magellan telescope is being built right now, which shows it's one of the best places on the earth for astronomical observations.

Mat Kaplan: Another telescope that we will be talking about I'm sure many more times on this program. Rodek, thank you again. Congratulations once again to you and the entire team. All of us I'm sure wish you many more discoveries of this sort using gravitational micro lensing as the work gets back underway with the OGLE experiment. And I hope that, that will happen very soon.

Radek Poleski: Thank you very much, and I hope we'll find many more fascinating objects and we'll try to report them.

Mat Kaplan: University of Warsaw astronomer Rodek Poleski is one of the discoverers of that lonely starless world. I'll be back with a whole series of stars beginning with Bill Nye right after this break.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What a year it has been for space exploration. Hi, I'm Sarah digital community manager for the Planetary Society. Will you help us celebrate 2020's greatest accomplishments? You can cast your votes for the most stunning image, the most exciting mission, the most surprising discovery and more at planetary.org/bestof2020. We've also got special year-end content on our social media channels. Voting is open now at planetary.org/bestof2020

Mat Kaplan: Long time listeners know that we've followed the progress of Planet FAQ for many years. Its creator HoneyBee Robotics learned not long ago that their radically simplified system for collecting loose material from the surface of pretty much any Rocky body in the solar system had been chosen for two upcoming missions. One to the moon and another to distant Phobos, the bigger moon circling Mars. We'll welcome HoneyBee vice-president and director of exploration technology, Kris Zacny and our Bruce Betts. First though, here's a couple of minutes with Planetary Society CEO, Bill Nye. Bill will be talking to Bruce Betts and Kris Zacny of HoneyBee Robotics in moments here. But I wanted to give you a chance to say something about this accomplishment.

Bill Nye: So everyone, we pulled this off. We got funding from support from our members. People like you to make a more efficient, cheaper way to collect samples from extra terrestrial bodies like the moon and Mars. This is really an advance. We increased the reliability of this, the amount of sample you can get. And we do it all using the free Helium. That's above the tanks of fuel on these spacecraft. It's just a cool idea. And it took years to get the details right, so that it would work reliably. But we'd got it and we've been selected on two missions. So thanks to our members. Thank you all for your support. This is one of the three pillars of our work at the Planetary Society. We advocate, we educate and we innovate.

Bill Nye: PlanetVac is an innovation. So along this line everybody, there's a fabulous word. It's not a big word, but it's a word you don't hear very often ullage, U-L-L- A-G-E. That's the space above the liquid in a tank. It's a space above the fuel in a spacecraft. And so to make sure that the fuel doesn't react to cause a chemical reaction with anything inside the tank and not contaminate the valves and have some pressure to push it through stuff. Traditionally, we fill the ullage above the fuel with Helium, which doesn't react to anything. It's the noblest of noble gases. We're using that leftover helium to do this important work. If you talk to a geologist and as I like to say, some of my best friends are geologists.

Bill Nye: They'll tell you that if you have a rock from Mars, you can tell who the president was. Okay you guys pull back, don't get so carried away. But what they're saying is there's tremendous amount of information in a sample brought back from the moon or Mars or an asteroid, the tremendous amount of geological information that is exciting. And so with your support, my member friends, we have a faster, better, cheaper way to do this. PlanetVac.

Mat Kaplan: Isn't this a great example of the kind of effort, the kind of project that the society looks for? I mean, we didn't pay for the whole thing, but what our members enabled us to do in supporting it was just enough to catalyze it.

Bill Nye: That's right. Mat, you hit the nail on the head. And we advocated for it. We said, "this is something that would work. This is a project we can pursue. It's not huge, but it's not nothing." And so I'm very excited about it. If we bring back more samples from Mars more cheaply, it's just going to be cool. Because the thing that I still want to do while I'm still alive Mat is find evidence of life on another world.

Mat Kaplan: Amen.

Bill Nye: Whether or not it's there, you have to search for evidence of life on Mars. That's just as logical as it gets. It's exciting and thanks for asking me about it. When you're in love you want to tell the world, as Carl said, he said and so I love PlanetVac. Except in airspace there's no sound it's just like that. But there's sound on Mars. There's sound on Mars, dog on it. And we're going to have microphones on Mars after February 18th, and we're going to have a Planet Fest and it's going to be big fun. And for me this is all part of the larger idea, that's the mission of the Planetary Society to know the cosmos and our place within it.

Mat Kaplan: I am looking forward to all of that. Sharing that with you and our members and everybody else out there. Thank you Bill, I guess in space no one can hear you suck. Can I say that?

Bill Nye: I guess you did. Carry on.

Mat Kaplan: That's Bill Nye, the CEO of the Planetary Society. Kris Zacny welcome back to Planetary Radio. It has been awhile. Bruce Betts, it hasn't been nearly as long for you but hey, welcome back as well.

Bruce Betts: Thanks Mat.

Kris Zacny: Thank you Mat. I'm super excited to be back on your radio show. It was a while. It's been couple of years.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. And it's been probably that long since I've had a tour of Honeybee's facility in Pasadena. I couldn't believe that it's also been two years. Bruce was it 2018? I think you went out there more than once, but that I got to go out and stand behind sandbags and watch PlanetVac on the foot of a Masten Space Systems Zodiac Rocket and watched it pull up some Mojave desert dirt.

Bruce Betts: Yes, almost completely correct. Except that it was Mars, so Mars simulant but it was in the Mojave desert and yes, it was two years ago and it was big fun watching the rocket flying with the PlanetVac and watching PlanetVac work so great.

Mat Kaplan: I still have I think a few flakes of melted reconstituted concrete from underneath the rocket motor. That was very cool.

Bruce Betts: I still have some of that in my hair. It is sore.

Kris Zacny: And I still have some of the sample.

Bruce Betts: Good you don't want to give that up. That's going to be worth a lot of money some day.

Kris Zacny: No it's hours.

Mat Kaplan: Kris speaking of samples, we are primarily here to celebrate this announcement that was made. It's still, as we speak only about a month ago that PlanetVac is going to the moon and going to Phobos. Let's talk about the moon first. You're going there. Courtesy of NASA?

Kris Zacny: Yes. So let's talk about the moon, right? Both Phobos and Arimona moons, let's talk about the bigger moon.

Mat Kaplan: Capital M moon.

Kris Zacny: Capital M moon. This is absolutely thrilling. It's a dream come true. It's just unbelievable how all the pieces came together. And a big role obviously Planetary Society. If you remember a couple of years ago we did end to end demonstration of the PlanetVac in our Mars chamber. And for the first time, we demonstrated that pneumatic sampling into some kind of a container is feasible in a vacuum environment. Up to that point, it was more of nice PowerPoint presentations get designs and people's imagination. But that was the first time we actually did that. To me that was the tipping point. NASA picked it up again. So up to bed point NASA spent SBIR or Small Business Innovative Research money developing technology.

Kris Zacny: But after the demonstration in Mars chamber the next big thing was a flight on the Muston Landor. Again big, big milestone for the first time we demonstrated that putting something on the leg of a lender is feasible that the leg can double as a something system. And as of this thing that touches the planetary surface called the rocket or Landor upright everything just came together. And finally, the announcement of CLIPS, the commercial net payload services. This is a new way of doing business. NASA and private industry in this of the PPP public private partnership. This is unbelievable successful venture. Bunch of good things that industry provides, a lot of things that NASA provides each of those sites bring the best to the table. And that's why this partnership works and CLIPS works. CLIPS works. So as part of clips, we were selected to fly PlanetVac to the moon to demonstrate this technology. We're flying to Mare Crisium on a mission called 19D. We do not know who is flying us in fact, either today or sometime next week NASA will select one of the 14 CLIPS providers to take us to the moon.

Mat Kaplan: No kidding.

Kris Zacny: Yeah, pretty soon we are going to know. Everything is very exciting. We're actually finishing all the slides getting ready for preliminary design review, which is going to happen beginning of December. We have critical design review sometime in July of 2021. And afterwards we are going to be cutting metal and getting ready for flight.

Mat Kaplan: That is very exciting. I know that one of those at least possible Landers, I mean Masten space systems, right?

Kris Zacny: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: That we were talking about it in the Mojave. You could end up again on their Lander.

Kris Zacny: Yes, definitely we could.We could. In fact, they already won one CLIPS contract to fly to the moon. They may be another flight for them. I'm sure they're eager to know. And we're also very, very eager to know. It's just gonna be great week next week [crosstalk 00:33:54]

Mat Kaplan: You were probably doing this a few days early. Bruce we'll have to mention that during the What's up! segment, when that Lander gets selected, that PlanetVac who's going to get its ride from. Bruce even before we go on to talking about this Japanese mission to Phobos, Bruce this is not just you, but all of us at the society, our members should be feeling pretty good about this.

Bruce Betts: You should be feeling very good about this PlanetVac is a perfect example of all we try to do with our science and technology program. And that members make happen by supporting key funding inserts into programs like PlanetVac when they need a funding boost, whether it be the end-to-end lab tests in a vacuum in 2013, where we funded a good portion of that, or whether we came in and funded a portion of the Masten flight of some of the work on PlanetVac, where there were critical monitoring needs. And we gave seed money that helped take it to the next level. Helped HoneyBee out with their fabulous technical expertise. And now we're seeing the ultimate payoff, which is the technology is flying, not just one spacecraft to one location but on two spacecraft to two locations. And I just want to publicly congratulate Kris and this whole Honeybee team because this has been quite the success for them.

Mat Kaplan: Was it around 2013 that I remember you and I going over to HoneyBee, their facility in Pasadena and shooting some video. And it's just hard to believe that it was that long ago that the program was then that earlier state and you've been our liaison with the company all along.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, unfortunately for Kris, they've had to deal with me all along. They got to deal with nice people too. Yeah. Yeah. It was a few years ago that we shot that glorious video hanging out in the HoneyBee shop with all sorts of toys. Although, I don't think they call them toys and I'm not allowed to touch them because...

Kris Zacny: They are toys.

Bruce Betts: I'm glad because that's how I think of them too.

Mat Kaplan: Let's go ahead and talk about going to Mars. Kris, I read now this lunar mission is a technology demo. So whatever sample PlanetVac picks up, I guess it won't be coming home. That's not what's going to happen on Jackson's Marsh and moon's exploration or MMX mission for that one. You should be bringing stuff back, right?

Kris Zacny: Yeah, absolutely. So the work that we've done with Musten and a these superb engineers, couple of years ago demonstrating planet they're going to footpad this work was done in something Mars Mojave simulant. So it's even closer to what we called pneumatic sampler or P sampler, that we'll be flying on a Japanese mission. Marshal moon's exploration to Phobos and Deimos. The primary goal of MMX is to explore both modes and touch down on the surface of Pablo's for two maybe three hours and bring some of the samples back. This sampler or pneumatic sampler is one of the two sampling systems that will be deployed. There is another one made by JAXA, Japanese aerospace agency which is a core sampler.

Kris Zacny: Core sampler is sort of like a push tube that robotic arm will push into the Phobos surface, we'll capture material from 10 centimeter below the surface and put it inside the sample return container. That primary purpose of a P sampler is to sample near surface material from the first few centimeters and deposit into the canister. Once we do that on the stroke of the Phobos, our job is not done yet. The spacecraft is going to go back into the orbit and once in orbit, robotic arm is going to come in, we'll pick up our sample canister and then insert it into sample return container. So it's going to be very robotic intensive mission for a first time. We going to be bringing sample, not just from Phobos, but also Martian sample. There's plenty of Martian ejector floating around Martian orbit and some of these stuff has fallen on the surface on the Phobos. So it's going to be not just the first Phobos sample return, but also Mars sample return mission.

Mat Kaplan: That's a very important point. Bruce, you've been involved with at least attempts to return samples from Phobos in the past one in particular. I know that you must be thinking of, as I say this, is there additional scientific significance to accomplishing a mission like this?

Bruce Betts: Yes, definitely Phobos and Deimos interestingly, there's still significant debate over where they came from. Did they form around Mars or are they captured asteroid? So the hope is with sample return, you would be able to resolve that as well as broader science questions about them.

Mat Kaplan: Kris when is MMX supposed to make it back to earth returning those samples?

Kris Zacny: Good question. So we launched in 24 and we're going to be departing on 26. So 26, 27 timeframe. We should be seeing samples back. They're going to reenter Australia somewhere in Outback Australia, just like Hayabusa one and Hayabusa two.

Mat Kaplan: Kris, before we let you go, I want to congratulate Honeybee Robotics on its contribution to the perseverance Mars Rover mission, which is now than halfway through. It's a journey to the red planet. What is HoneyBee's role in that mission?

Kris Zacny: For this mission that we had to Segway slightly away from bread and butter robotic system that we normally do. For us perseverance offered completely new challenge. And the challenge was developing a hardware that we call a witness plate assemblies. A witness plate assemblies is a plates and screens and serves, put together into something that looks like a chalk cylindrical, centimeter diameter, couple of centimeter long cylinder. It's job is to witness all the contamination that the rubric has witnessed from a clean room all the way to Mars. And during martian operation. There are five of those. They're sitting in sampling tubes, some of it will be exposed only on Mars and they will witness the environment around the rubric.

Kris Zacny: Once those five something cubes are witnessed with assemblies when sampling tubes come back, they're going to be analyzed to determine what sort of forward contamination we have brought with us in terms of molecules and the particular contaminants. And once we know that we're going to examine rock samples and soul samples that we bring from Mars to determine if we see exactly the same contaminant and by looking at the two and comparing the two we'll know whether material is indeed pristine marshal material or whether it has been contaminated by the Rubik itself. So they extremely important, extremely important. We need these witnesses in order to be absolutely sure about the science that will be coming back by analyzing those samples. To HoneyBee this was very first hardware that has to reach extreme level of cleanliness. This is probably the cleanest hardware that has ever flown in space. It was amazing challenge. And this is also going to be the first hardware that will be coming back from Mars. And we're super thrilled about it.

Mat Kaplan: Sounds like a pretty important role to play on this sample return mission from Mars. Bruce, I want to give you a chance once again, turning to you as a scientist to remind us of why sample returned from Mars from the surface in this case has remained such an important goal.

Bruce Betts: Well, sample return of any kind you get a lot of benefits from not the least of which is that no matter how good our technology goes that we fly on our spacecraft. It's still so limited in mass and volume and capability that if you can get samples back to earth, then you have the full laboratory capability and instrumentation of earth to work with. And also the samples can be analyzed by multiple scientists in multiple ways. If you can get samples from Mars with context of what geologic unit you took them out of, then you can bring them back use earth laboratory equipment and really dig down and get a whole other layer of science, much deeper and more profound discoveries or at least that's what happens. That's certainly what happened with lunar samples every time we've done sampling in the solar system. Hopefully with PlanetVac, it'll happen with Phobos.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce don't go away because in a few minutes, so we'll bring you back to tell us what's up in the night sky. But Kris, I'm sure this isn't the last time that we'll be talking either best of luck with all of these efforts underway. And there are others we could talk about and maybe we'll on a future episode of Planetary Radio, but I guess most immediately best of luck with that upcoming February landing on Mars and the performance of HoneyBee Robotics hardware on the perseverance Rover.

Kris Zacny: Thanks Mat and I appreciate all the work Planetary Society has done to advance this technologies. Dream come true. And I'm thrilled that Planetary Society is part of this. Thanks everyone.

Mat Kaplan: As a member, I am very proud that we have had that involvement and Bruce that you've been able to coordinate it all for us. You heard there HoneyBee Robotics vice-president and director of exploration technology Kris Zacny. Also joining us was the Planetary Society chief scientist, Bruce Betts. And as I said, he'll be back with us for what's up.

Bill Nye: Seasons greetings! Bill Nye here, the holidays are racing toward us. We've got the perfect present for the space enthusiast in your life. A gift membership to the Planetary Society will make her or him part of everything we do like flying our own Light Sail spacecraft; two of them, advocating for space exploration, keeping our planet from getting hit by an asteroid. And this show. Sure. You'd like to give them a ticket to the moon or Mars, but I promise you, this is the next best thing. Memberships start at $50 a year or just $4 a month. We've got discounts for students, educators, and seniors. Visit us at planetary.org/gift to learn about the benefits of membership and how easy it is to give someone special, the passion, beauty, and joy of space. That's planetary.org/gift. Thank you and happy holidays.

Mat Kaplan: Time for What's Up on planetary radio. Bruce Betts is the chief scientist of the Planetary Society. And as such, in addition to telling us what's up in the night sky, he has some other duties including going to conferences and representing us. And you did that last week. Can you tell us about it?

Bruce Betts: Sure. I went to the... Well, virtually went to the office team minus nine years workshop.

Mat Kaplan: Ooh. So nine years now, close pass. Right? Remind us how close is the big rock going to come?

Bruce Betts: Big rock will come closer than our geostationary satellites. So few worth radios. There will be visible looking like a third magnitude. So fairly bright star passing across the sky if you're in the right half of the world, which would be Europe and Africa and Western Asia.

Mat Kaplan: So put it on your 2029 calendars everybody. I know I am. What did you come up with at this conference? What was it all about?

Bruce Betts: I was trying to figure out how to best use this opportunity for science, for planetary defense, protecting the earth from asteroid impact. Again this isn't going to hit in the near future anyway. But I was presenting along with my colleague Casey Dreier, that this is a real opportunity for education about planetary defense and asteroids in general, education about risk and use it to get the good information out there early, the correct information and try to head off some of the undoubtedly bogus information that will come out as we grow closer to the encounter.

Mat Kaplan: That's right up our alley. So very appropriate. And we're not done talking about asteroids but what else is up there? What's up there right now. We don't have to wait nine years to see?

Bruce Betts: Yeah. A bunch of asteroids if you have big telescopes. But otherwise bunch of planets, if you have decent eyesight and no clouds, we've got Jupiter and Saturn still hanging out in the Southwest. And the early evening, Jupiter being the much brighter one on the 18th of November, the crescent moon will join them for a lovely little triplet. And then we've got Mars up in the evening as well over towards the East, the Southeast. And it's still looking super bright, but it is fading gradually as earth and Mars get farther away. And then in the predawn sky dominating, the East is super bright Venus. We've also got an apparition of Mercury are going on right now below Venus to its lower left Mercury looking like a bright star not nearly as bright as Venus, but still bright, but always low to the horizon. So I get a clear view to the Eastern horizon and the pre dawning Savina's and below it Mercury. And if you look on the 13th of November, you will see a moon hanging out. It's our moon. It's the moon. Just to be clear.

Mat Kaplan: Capital M moon. As we, as we said during one of the conversations today.

Bruce Betts: Indeed, let us go on to this week in space history. There are some significant... a lot of stuff happened. I'll mention just a couple of them that are having factors of 10 anniversaries. 50 years ago this week, Luna Cod one became the first Rover on another world on the moon in 1970. 10 years later, so 40 years ago, Voyager one did it's fly by of Saturn.

Mat Kaplan: Good ones. Yeah.

Bruce Betts: All right. On two, four, three, two, one random space bag, random space bag, Novage skin association of Russia in 1993, they saw Luna Cod two and the Luna 21 Lander that went along with it at a Sotheby's auction. These are on the moon to be clear. And for 68,000 US dollars Richard Garriott bought them. And to my knowledge still owns them. Richard Garriott the son of astronaut Owen Garrett, and an astronaut himself as a space tourist, computer gaming entrepreneur Owen's Luna Cod two and Luna 21.

Mat Kaplan: I hope that somebody hasn't stolen the wheels by the time he gets up there.

Bruce Betts: I believe in a Luna caught on blocks are still worth something. And you can always hang out in the trailer park next door.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah right. Lunar trailer trash that's-

Bruce Betts: All right. Bring us back from this weird place we've gone. Let us take you to the weird place of the trivia contest. As of now as measured by average diameter or equivalently volume. What is the smallest asteroid that has been visited by a space craft? How do we do?

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to start with this. He's not our winner, but Andrew Miller in Ohio said for all the people who like to send poems with their submissions, I'm really looking forward to finding out how they rhyme eta Couwa. Is he incorrect?

Bruce Betts: Yes, he is correct. The target of the Hayabusa sample return mission.

Mat Kaplan: Andrew, I'm afraid we're going to keep you in suspense. Here is Dave Fairchild, our poet laureates response back in 1998, and asteroid was found a rebel pile up in space that wasn't even round. Instead it had a peanut shape and it was kind of small compared to other Neos. Well, it's hardly there at all but EDA cow got the nod with Jackson's claim to fame. They harvested some particles when Hayabusa came, then brought them back to earth again like space-time caviar. This asteroid is the smallest that we've visited so far.

Bruce Betts: Nice

Mat Kaplan: Here is our winner. He last one, four and a half years ago. Talk about hanging in there for a second shot. Yeah. Hudson Ansley in New Jersey who said, "yeah, two, five, one, four, three, Eda Couwa. Congratulations, Hudson. Hope it was worth the wait. You are also going to be waiting a little while at least to pick up a planetary society, kick asteroid rubber asteroid. It has not yet been visited by any spacecraft as far as we know.

Bruce Betts: But if it were, it would definitely be the smallest. We didn't mention eda couwa about 350 meters average diameter.

Mat Kaplan: Kirk Zuora mentioned that he also said that it's confirms peanut shape factor of 0.9. I didn't know. There was a peanut scale. Is that something Mr. Peanut came up with?

Bruce Betts: Yeah. The trick is you have to look at all the pictures. The asteroid are wearing a monocle.

Mat Kaplan: That's so fun. It's really out of... If I knew Photoshop Ben Drought, apparently imaginary town of Ames Hawaiis where he says he's from. He says as small as it is, it would fill five vehicle assembly buildings, 71,000 foot great lakes or ships to haul.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I was just wondering that.

Mat Kaplan: Pablo Carmesia in Belarus loves the Hayabusa mission story, similar to the adventures of Mark Watney on Mars, only cooler because everything went wrong. Despite all the breakdowns and failure of three of four engines, Jack's specialists still managed to obtain samples from the asteroid surface and return them to earth. Ian Jackson in Germany, who's looking forward to the dark mission. That's going to Didy moon just 116 meters in diameter. He says, "it'll fly into it. And if the surface is anything like Benue, fly straight through and come out the other side."

Bruce Betts: Well, I don't think it's big enough to do that, but it may kick up an awful lot of stuff,

Mat Kaplan: References to rubble piles up there. But as John Burley pointed out, while it may have been the smallest one yet visited at about 350 meters, it's still big enough to ruin your day.

Bruce Betts: Oh yeah. By the way, for anyone wondering the dark mission is the double asteroid redirection test.

Mat Kaplan: Guess we're ready for another one.

Bruce Betts: Here's your question. Who named most of the lunar Maria with the names that are used today? By which to be clear, the international astronomical union approved names of the Maria features on the moon. So who named most of them? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest?

Mat Kaplan: You have until the 18th, that'd be November 18th at 8:00 AM. Pacific time to get us the answer and we have a pretty cool prize for you. Bill Nye has a new book out for kids 10 and up. It's called Bill Nye's great big world of science. And so coauthored with Gregory moan. We're going to send the winner out there a copy and it'll be signed by Bill, not bad. I think it's coming from his personal stash of these books which just came just a couple of weeks ago.

Bruce Betts: Cool.

Mat Kaplan: And that's it.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there and look up at the night sky and think about how much you'd pay for an old robotic spacecraft on the moon. Thank you and goodnight.

Mat Kaplan: You think they'd have taken something in barter? I've got an old drone here that doesn't work. But I doubt the Rover does it anymore either.

Bruce Betts: Oh, you might be able to get one of the crash spacecraft.

Mat Kaplan: That's Bruce Betts. He is the chief scientist of the Planetary Society, which joins us every week for Whats up.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its members rogue and otherwise. Mark Hilverda is our associate producer. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth