A.J.S. Rayl • Feb 02, 2019

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Logs 15th Year in Silence, Team Begins 'Hail Mary' Efforts

Sols 5311–5341

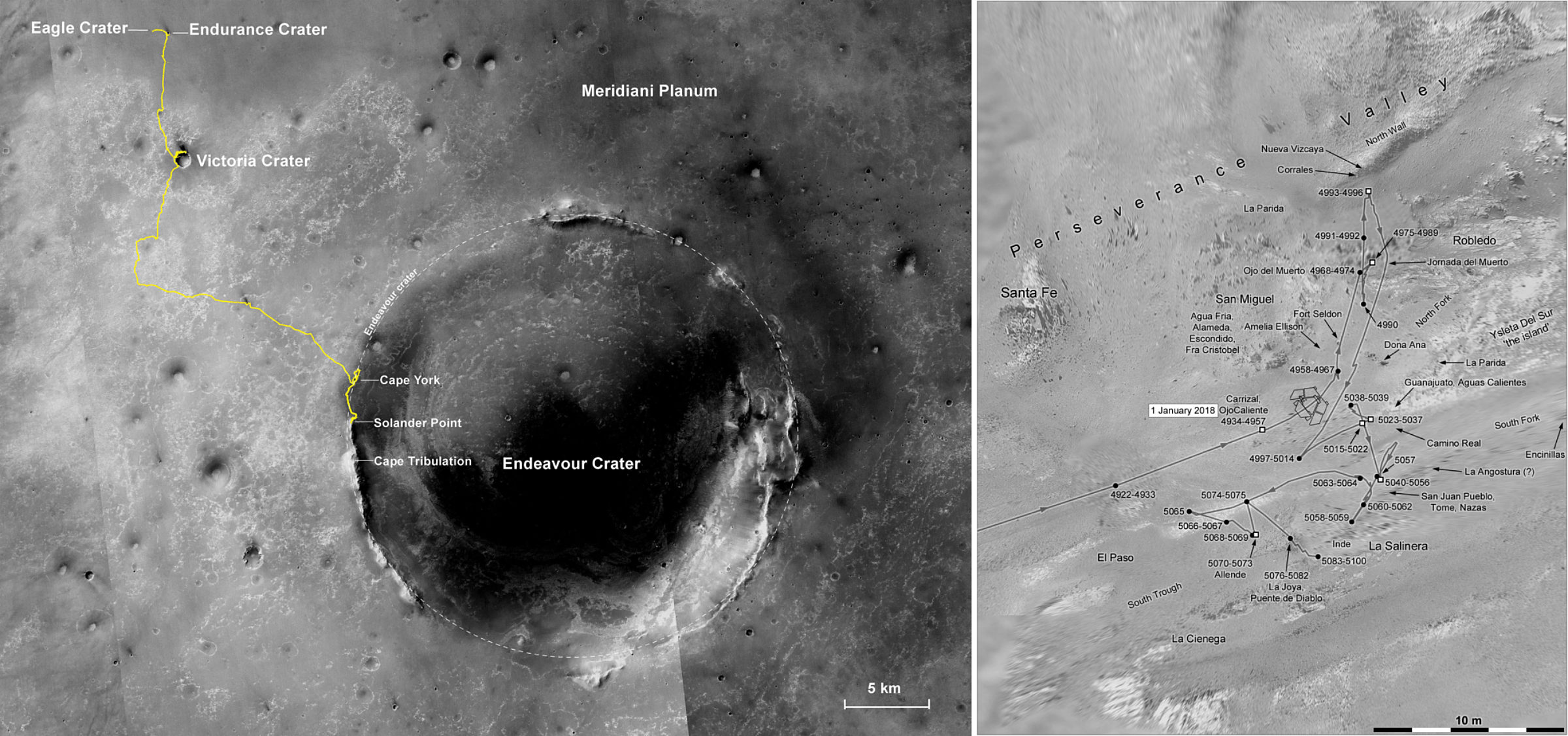

As a string of dust storms moved through Meridiani Planum and over Endeavour Crater in January, Opportunity silently wrapped her fifteenth year on the surface of Mars. While the storms raised enough dust to turn the skies noticeably hazy all around the planet, they also raised hope that Mars might gift the veteran robot field geologist with gusts that would finally clear the ‘bot’s solar arrays and enable her to recharge, wake-up, and phone home.

But at month’s end, the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) team and colleagues at the Deep Space Network (DSN) neither saw nor heard any sign of the legendary robot. At the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where all of NASA’s Red Planet explorers have been born, Opportunity’s 15th anniversary came and went quietly in the halls of MER.

After spending seven and a half months reaching out to and listening for the longest-lived robot on Mars and transmitting more than 600 recovery commands, the silence is deafening for the team. Still, no one is giving up, not yet.

“We’re still trying,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “We’re still in the window when we’ve seen cleaning events in the past and we are continuing to attempt to communicate with the rover in every way we can.”

With NASA’s support, the MER team is committed to doing everything possible to make contact with the record-setting, crater-hopping, marathon-roving veteran explorer loved around the world. To that end, within hours of the Opportunity’s 15th anniversary, the operations engineers began launching a series of last-ditch efforts.

The team last heard from Opportunity on June 10, 2018, the rover’s 5111th Martian day (or "sol") on the surface of Mars. It was a sparse communiqué, but it revealed a monster storm – which would soon become a planet-encircling dust event (PEDE) –– had turned day into night at Endeavour Crater. Not long after the team received that downlink, the solar-powered rover presumably shut down and went to sleep in an attempt to survive what would turn out to be the worst global dust event that NASA has ever recorded.

Since then, the MER ops team has been trying to re-establish contact with Oppy, as she is affectionately known, through the DSN antennas. They have been conducting "sweep-and-beeps" to try and find and lock onto Opportunity’s signal and electronically nudge her to respond, and have also been reviewing all the signals emanating from the Red Planet, which are recorded by DSN’s highly sensitive Radio Science Receivers, as covered in previous MER Updates.

During the last couple of months, the ops team has expanded the breadth of the "sweep-and-beeps" during the mission’s daily pass or timeslot on the DSN to include more times of the day on Mars and has been using both wave configurations of the rover’s frequency, known as right-hand circular polarization (RCP) and left-hand circular polarization (LCP).

A leading hypothesis has been that the global storm deposited so much dust on Opportunity’s solar arrays that she hasn’t been able to effectively power up and phone home. Thus, the windy period that began in mid-November 2018 and will close out the Martian summer has been cause for optimism.

Historically, the rover has always been “cleaned” to some degree by these seasonal Martian winds. Still, the team hasn’t heard so much as a ‘beep’ from Opportunity and the summer winds usually begin to die down at the end of January.

“We always said that we would try multiple techniques,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of JPL. “Our hope was that in this dust-cleaning period from November through January we might get a cleaning event that could enable the rover to power up, if in fact the rover is just silent because there was too much dust on the arrays. But we still haven’t heard anything.”

The MER team though has long subscribed to the Yogi Berra philosophy that “it ain’t over ‘til it’s over.” So, not long after Opportunity’s 15th, the MER ops team began transmitting the first in a series of “Hail Mary” commands, “low likelihood things that would address potential recoverable multi-fault situations on the rover,” as Callas described them.

While the MER battery experts at JPL, Marshall Smart and Kumar Bugga are confident Opportunity’s batteries pulled through the global storm, and power and thermal models indicate that the rover should have made it through the storm and these last seven months with relative ease, many of the MER class rovers’ parts and systems are “single-string.” That means there is no redundancy and if something along those single strings breaks, it’s mission over.

Through the last decade and half, Opportunity has proven every rove of the way to be “Little Miss Perfect,” as former Chief of MER Engineering Jake Matijevic, one of the original MER creators, nicknamed her way back in the beginning. So perfect that it’s hard for many followers and even team members to believe the end may be near.

Of course, as magnificent a marvel as Opportunity is, it’s certainly well within the realm of reason that something somewhere unknown has happened – a component failed, a solder joint broke, a cable tore, or any number of other things – that may have already silenced the rover forever. With no data from the surface, there is just no way of knowing what’s happened.

“Opportunity hasn’t talked to us and that’s what could tell us what’s going on,” said Callas. “We have to accept the fact that this is now a 15-year-old rover. Something else [beyond dust on the solar arrays] could have gone wrong.”

In those single-string scenarios, there is clearly nothing the team could do from a commanding standpoint to recover Opportunity. However, it is also possible that there has been a failure within the rover’s telecommunication system that has prevented her from transmitting even a ‘beep.’ If that is the case, it is conceivable that this team – which gained renown for its workarounds – could fix the problem because with two X-band solid state power amplifiers (SSPAs) or radios and a UHF transmitter, there is built-in redundancy in this system.

This new series of “Hail Mary” commands are “strategies to try and force Opportunity to talk to us,” said MER Spacecraft Systems Engineer and Flight Director Michael Staab, who was tasked last September with overseeing the development of these efforts.

During the next several weeks, the MER ops engineers will be addressing three scenarios that could have occurred and which could be fixed with commands from Earth. Perhaps the rover's primary SSPA that Opportunity has used to communicate with Earth since landing has failed. Or maybe both the rover’s primary and secondary (or back-up) X-band SSPAs have failed. Or it could be that the rover's onboard clock is “off-set.”

On January 25th, the MER ops team began transmitting the first of these “Hail Mary” efforts, commanding the rover to switch to her backup SSPA or radio. “We're reviewing all the downlink data and so far, nothing,” said JPL’s Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson at month’s end.

“The last year has been a really tough one for Opportunity environmentally,” said MER Power team lead Jennifer Herman.

Even the global storm that stopped Opportunity in her tracks last June was a little worse than it was originally estimated to be. In recalibrating the data from that storm, Athena Science Team member Mark Lemmon, aka “the Tau guy,” of the Space Science Institute, estimated the atmospheric opacity, described simply by the team as the Tau, to be 11.1. That is the highest estimated Tau on Mars since NASA has been sending spacecraft there, and higher than his original estimate of 10.8.

“After that historic dust storm, there must have been an incredible amount of dust deposited on the solar arrays,” Herman said. “My hope was that Opportunity would experience a more typical late summer, with Taus around 1.0 and gentle winds constantly cleaning the solar arrays.”

That didn’t happen. Instead, Mars sent several regional and local dust storms Opportunity’s way. “Hopefully, some of these storms cleaned off the dust on the solar arrays instead of dumping more dust on them, but we just don't know,” said Herman. “Either way, the atmospheric dust these storms raised reduces the amount of sunlight reaching the rover."

Despite the ‘dusty writing on the wall’ and even though many of the MER team members have already moved to other missions, hope among many of the passionate, committed, devoted MER team members still floats, at least a little.

“We’ve tried everything except these last few ‘Hail Mary’s’,” Squyres said. “But we’re giving them a shot. It doesn’t cost that much and we want to try everything we can. We’re doing our due diligence.”

Protected by airbags, Opportunity bounced onto the surface of Mars January 24th Pacific Standard Time (PST) right on target with a landing system conceived by Rob Manning, now JPL’s Chief Engineer, and then scored Earth’s first interplanetary 300-million-mile hole-in-one as she rolled into Eagle Crater. It was an incredible, awesome landing and the whole world was watching and applauding.

Along with her twin, Spirit, Opportunity was “warrantied” for just 90 days. In fact, few outside the team had any faith that both rovers would land and complete their primary missions. But the intrepid rovers and their equally intrepid team on Earth had other plans.

“Maybe we have made it look easy for fourteen-and-a-half years,” said Callas. “But Mars is reminding us, this is not easy.”

As 2019 rang in on Mars, a dust storm that crossed into southern hemisphere along the Acidalia storm-track turned regional about 1100 kilometers (683.50 miles) west of Opportunity and hung out in that general area churning the rusty red powdery stuff of Mars into the atmosphere from New Year’s Eve through January 6, 2019. It would be the first in a string of storms that blew through Meridiani Planum in January.

Since this is the time of the Martian summer when the winds are especially active and can turn into powerful gales that grow into regional storms and even planet-encircling dust events (PEDEs), this was expected, even anticipated, said Mars weatherman Bruce Cantor, of Malin Space Science Systems, who produces weekly Mars Weather Reports from data taken by the company’s Mars Color Imager (MARCI) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

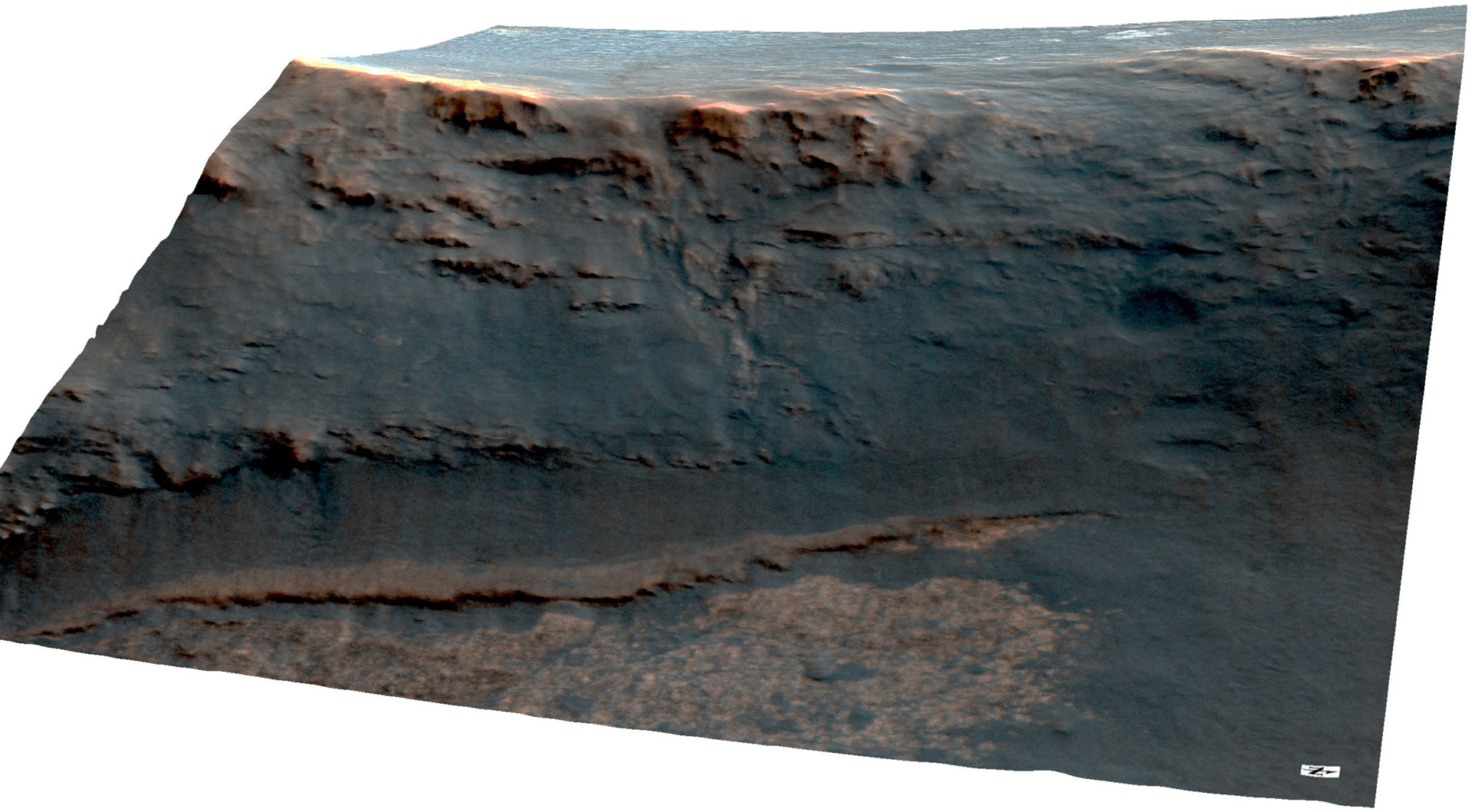

As it turned out, Opportunity would experience the effects of “three cross-equatorial regional storms” from her post about halfway down Perseverance Valley, where she has been hunkered down since June 2018. “This is the exact time during Mars years when we see these types of storms,” Cantor said. “And it’s these regional storms that elevate the background opacity globally during the late southern summer/northern winter seasons. In fact, we knew and forecasted that one of these storms would be a massive dust-raising event. This also wasn’t a surprise, because there is a lot of dust available for lifting following the fallout phase of a PEDE, especially the historic, planetary-scale one that caused the rover to shut down last year.”

A “much larger storm,” which Cantor documented on January 5th about 200 kilometers (124.27 miles) west of Endeavour evolved and merged with the dust cloud of the first storm on January 7th, causing the skies to become noticeably hazier in orbital imagery. That Martian merger moved over Opportunity from January 9th through the 12th, hitting the ‘bot with “a glancing blow” and the atmospheric opacity or Tau at Endeavour rose to above 1.5 within that period, he said.

By the time Opportunity’s anniversary came around, this second regional storm was abating, though it continued lifting dust through the rover’s special day on January 24th. Miraculously, all things considered, Oppy dodged those dusty bullets, but she was still not out of danger.

Overlapping with the second storm, a third storm grew into a regional guster and lofted a substantial amount of dust throughout the third week of the month, from January 15th through the 22nd, and there was some concern it could evolve into another planet-encircler. “Our MARCI observations were too close to the limb to model or even guesstimate a Tau measurement,” said Cantor. But they could observe that a diffuse cloud that it created extended over Opportunity’s site on January 19th and 20th.

Suffice to say, the storms of January darkened Opportunity’s doorstep. But by month’s end, the third in the string of storms was fading and the atmospheric opacity was returning to a seasonal “normal.” The only good news is that Cantor’s Tau estimate at month’s end, based on his visual inspection of orbital imagery, was “less than 1.5,” he said.

As the MER team learned long ago, as the Martians winds give, they also consistently take. “But whether those storms added to, or subtracted from the dust on Opportunity’s solar panels we do not know,” said Rich Zurek, Chief Scientist at JPL’s Mars Program Office, and Chief Scientist of the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

Meanwhile on Earth, Americans woke up to a government still in a shutdown that began on December 22, 2018. Since Caltech manages JPL, the engineers and scientists there are not civil servants like many of the employees in other NASA centers, which are managed by the space agency. That enables them to stay fully engaged, despite the fact that communications between NASA and JPL were effectively non-existent as a result of what would become the longest U.S. government ‘shut show’ on record.

The MER ops team pressed on throughout the month. By the end of the day on January 24th, the engineers had sent a grand total of “605 sweep-and-beep commands, 424 on RCP and 181 on LCP,” said Nelson. Still, they heard nothing from Opportunity.

In the meantime, Nelson, Staab, and most of the MER engineering team met with the MER Dust Storm Review Board, which is made up of subsystems experts in Telecom (Jim Taylor and Ryan Mukai), Thermal, Avionics (Glenn Reeves), Fault Protection (Tracy Neilson), and Systems (Beth Dewell and Rob Manning), along with a representative from the Mission Assurance Office.

During that meeting, Staab presented the ops engineers latest plans for the “Hail Mary” strategies, tweaked and updated over the past several weeks as a result of testing them out in the rover test bed at The Lab. The recommendations that Staab’s team briefed to the review board were summarized and delivered to Callas, who then reported them to Fuk Li, JPL’s Director for the Mars Exploration Directorate.

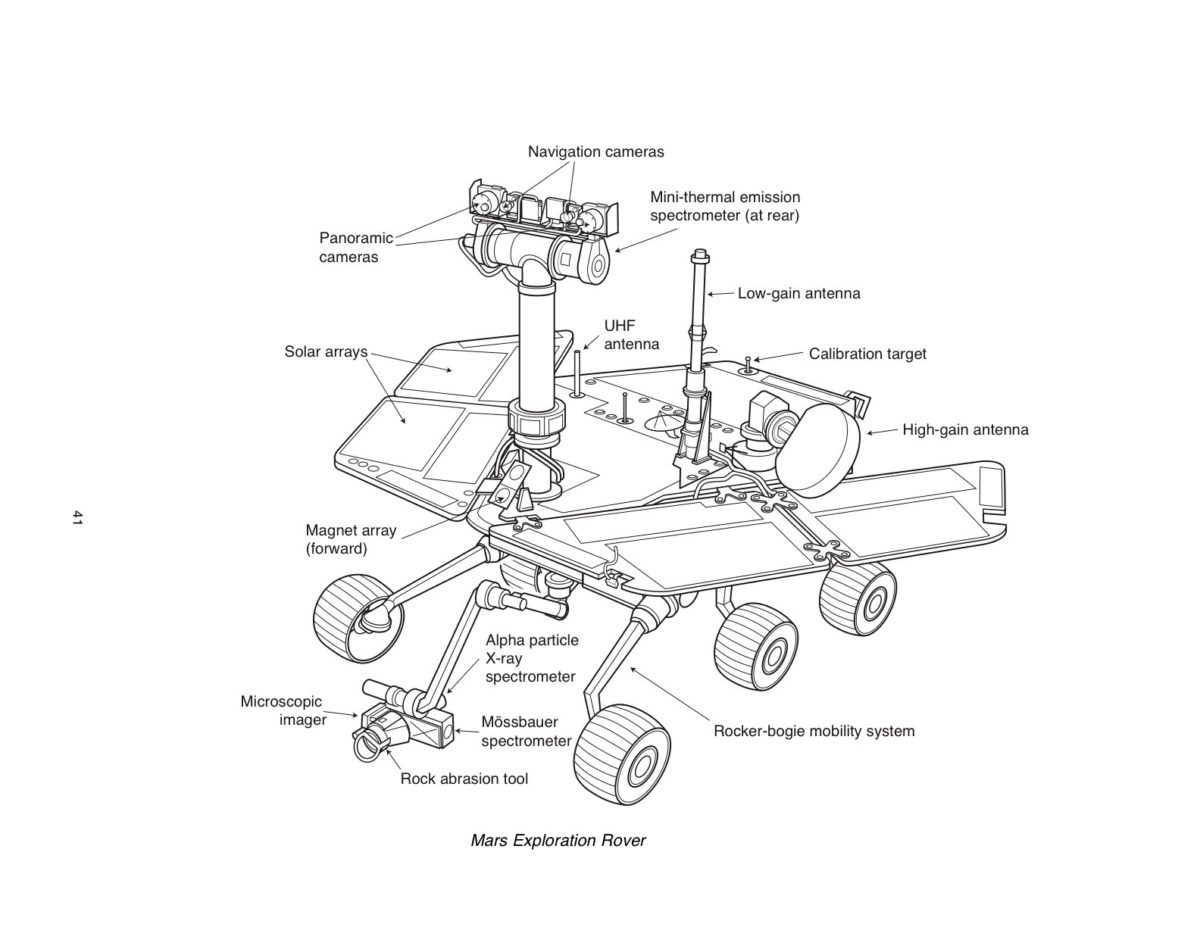

“We looked at alternative possibilities,” said Callas. “If it’s not just dust on Opportunity’s solar arrays that is preventing the rover from talking to us, if there’s something else wrong with the vehicle, what could be wrong that is correctable? One of the few areas where we have redundancy is in the telecom system. We have two solid-state power amplifiers (SSPAs) or X-band radio transmitters, and we have a UHF system.”

If something had gone awry within this redundant system, the engineers could do something about it by sending commands to Opportunity. So, since last September, that’s where Staab and his team focused much of their attention in determining the what-ifs and what the “Hail Mary” efforts would be.

“The rover ‘beeps’ and performs direct-to-Earth (DTE) communications through the primary X-band solid state power amplifier (SSPA) or radio when we have normal X-band passes. And this primary X-band SSPA is how we expect the rover would send its beep or autonomous fault windows back to Earth,” said Staab.

But what if the primary SSPA that the rover has used since landing on the surface failed for some reason? “That could be a reason for why we haven’t heard from the rover,” Staab said. “In that scenario, when the rover would try to talk to us, we wouldn’t hear it, because the transmitter is gone.”

The objective then for this “Hail Mary” is to have the rover switch to the back-up X-band SSPA – which, Callas pointed out, has never before been used in flight – to see if they could force a response from the rover using that transmitter.

“Opportunity, however, should have exercised that as part of a fault recovery if it had been actively waking up and not talking to the Earth,” noted Callas. “But there are some scenarios where the rover doesn’t completely wake up or doesn’t get a chance to fully exercise the fault protection to realize that it has a broken SSPA because it browns out too quickly and goes back to sleep. It’s possible that the rover wakes up briefly, but before it can exercise the fault protection that would initiate the switch to the alternate X-band SSPA, it goes back to sleep, and then it browns out again on the next wake-up too,” he explained.

Just hours after Opportunity logged her 15th year on the surface of Mars, on Sol 5334 (January 25, 2019) – the same day the longest U.S. government shut down on record finally came to an end – the ops engineers, who had been given the green light to initiate the “Hail Mary’s,” began sending commands to the rover to make the switch to her back-up X-band SSPA. “Since then, all commanding has requested the backup SSPA with a total of 21 LCP commands and 13 RCP commands sent between Sol 5334 and 5338 (January 25 and January 29, 2019),” said Nelson.

“These first ‘Hail Mary's’ simply ask Opportunity to talk to us using her backup X-band SSPA rather than using her primary SSPA,” Nelson continued. “We do our ‘asking’ using either RCP or LCP, since if the fault protection is running it will attempt to alternate the rover receiver between RCP and LCP. Commanding on the backup X-band SSPA covers the case of not hearing because the prime X-band SSPA is bad.”

Everyone agrees that the possibility both SSPAs are gone is probably not probable, because it would have taken a series of “unlikely” events for either of those transmitters to fail. “The only way one of those SSPAs could have broken is if it just randomly failed for some reason and there’s no reason for us to think that it would just randomly fail in the middle of a dust storm,” said Staab.

“While we have no reason to believe that temperatures could have caused a failure, we do have to consider age,” noted Kevin Reich, one MER’s Tactical Downlink Leads and System Engineers, who has been working with Staab on the “Hail Mary’s” since September. “The primary SSPA has been operating for more than a decade longer than it was intended to operate, beyond surviving unpowered for more than seven months on the trip to Mars. And, another thing we have to consider is that we don’t actually know if the backup SSPA survived launch, cruise, EDL, and 15 years on the surface unpowered.”

Time will tell, or not.

Another outside prospect is that Opportunity’s clock is off-set. How would that happen?

Once the rover’s batteries drop below 16 volts, the mission clock – which is the only clock on the vehicle – powers off. “If the vehicle then establishes sufficient charge to power the clock back on, the clock would be seeded with a value stored in non-volatile memory, what we call the recovery time,” said Staab. “And because the recovery time likely does not match the ‘true’ time, the clock is said to be ‘offset’ from reality.”

“The clock should be the first thing to come back online and start ticking as the batteries charge back up, added Reich. “When the fault response runs, the clock will be re-initialized to that known value stored in its non-volatile memory, but the clock could be reseeded at any time on the sol it wakes up. This would almost certainly cause Oppy to think it’s a different solar time than it actually is and that will affect when she wakes up and whether or not she can talk to Earth.”

The extent of this offset can be on the order of months. “But the real danger is in the difference between what the rover believes is true solar time vs. actual time; for example, is it 09:00 local solar time (LST) or 13:00 LST when it’s actually 10:00 LST?” said Staab.

In any case, an off-set clock would leave Opportunity “so confused” about the time that she never gets a chance to talk to the Earth; consequently, the engineers have never been able to catch the rover with a ‘beep’ command, said Callas. “Or it could be that the rover never had enough power to do a ‘beep’ command because it browns out immediately because it’s not sleeping at the right time.”

If the rover is not DeepSleeping at the right time – that is, nighttime – that could be preventing the rover’s ability to charge up its batteries. It’s “essential” for the rover to be DeepSleeping at night, Callas noted. “We have this stuck-on heater that we’ve had since Sol 1, so if the rover doesn’t DeepSleep at night, then whatever power it charges up during the day is going to get lost to the heater, because that thing is likely going to consume the power we’ve tried to collect, and therefore is undermining the rover’s ability to charge,” he said.

“The clock off-set, coupled with a high Tau/low dust factor, could create this scenario where the rover may only be waking up for a few minutes every sol and just doesn’t have sufficient charge to talk to Earth via the X-band transmitters,” added Staab.

So, in coming sols,the engineers will also try tore-set the clock in the blind, with no data on the ground to tell us what’s happening. The team knows the clock has to have faulted at some point during the last seven and half months.“Maybe that command will get in and the rover will go: ‘Oh gee, I’ve been sleeping at the wrong time,’ and then start to normally sleep, which would allow the batteries to charge,” said Callas.

“In this scenario, we re-set the rover’s mission clock in the blind and immediately shut the vehicle down for DeepSleep, allowing it to charge through the day until a potential X-band response would be possible,” said Staab. “As long as we have the power to support that window, we would see it in our recordings from the DSN’s Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) science receivers, the VSRs in the signal processing center. However, if the transmitters are indeed bad, we wouldn’t see anything in the VSRs,” he said.

Even if both X-band SSPAs are gone however, Opportunity could still communicate through her UHF system, which is completely separate from the X-band transmitters. That’s the redundancy in the rover’s telecom system.

In that scenario, the team would send commands that essentially “force Opportunity to stay awake until one of the orbiters comes over,” said Staab. “If those commands got in, theoretically the rover would hail the orbiter and send the data up to the orbiter using its UHF transmitter,” he said.

The engineers will also uplink some UHF communication windows, because Opportunity’s last communication windows expired months ago, and the rover would need those to successfully communicate using the UHF transmitter. If there are no UHF comm windows, then the rover wouldn’t even try to phone home through the UHF system.

Once the UHF comm windows are uplinked, the MER team will be listening for Opportunity with the orbiters, most likely MRO, because that spacecraft orbits over Endeavour during in the most favorable time of the Martian day at Endeavour. “If this ‘Hail Mary’ strategy works, then the rover would send her transmission via the UHF up to the orbiter and the orbiter would relay the data to Earth,” said Staab.

If the MER team does receive orbiter data, then they would know Opportunity is alive, so to speak, which would confirm “something is suspect with the X-band radio transmitters,” said Staab. “This approach allows us to clear the mission clock fault response and get Opportunity charging its batteries; test for failed X-band transmitters; and have a secondary path for receiving a response. We can take care of three ‘Hail Mary’ scenarios simultaneously, which is advantageous given the limited amount of time we have left to command a vehicle response,” he explained.

Sending a command in the blind to re-set the clock is, said Squyres, “a somewhat crazy thing” to do. Some people in the space community might argue each of these commands are somewhat crazy. But in theory each of these strategies could work – if, that is, these scenarios are real and not hypothetical.

“Given that we haven’t heard from Oppy yet, everything along the X-band transmit path is suspect, from the software behavior out through the antennas,” Reich offered. “There are innumerable fault scenarios that the rover could be facing right now. These final strategies are designed to address as many of the scenarios that we have identified as recoverable.”

“There’s a reason they’re called Hail Mary’s. They are last ditch,” said Staab. But these are the scenarios where we really think we could get the rover out of whatever situation it’s in right now.”

Anything is possible, as the age-old adage goes, and if any of these Hail Mary’s work, then engineers could attempt to recover Opportunity. That would take some time because they would first have to command the robot out of a low-power fault, an up-loss timer fault, and the mission clock fault if the clock re-set didn’t work. “The most important thing we can do for Opportunity is resync the clock and transition the rover out of the mission clock fault state,” said Reich. “If we can’t do this, she won’t survive the coming winter.”

With summer on the run, Opportunity and the team are running out of time. Although during one Martian year the winds blew well into March and successfully cleared some of the accumulated dust from the rover’s arrays, the dust storm season and the windy season within the summer season, for all intents and purposes, will be over soon.

The fall equinox occurs March 23, 2019. “That’s when the dust cleaning season, arguably, ends,” said Herman. “The start of fall is when I usually make tilt recommendations to the team, based on dust trends and energy requirements. It's important for us to drive the rover to a good northward tilt to generate enough energy to survive the winter. But if we haven’t heard from Opportunity by then, we won’t be able to do that.”

Winter follows fall on Mars, just like on Earth, and when the winter solstice in the southern hemisphere arrives October 8th, the temperatures will drop to rover-threatening lows ofaround -70 degrees Celsius (-94 degrees Fahrenheit). These extreme temperatures are likely to cause irreparable harm to an unpowered rover's internal wiring computer systems and/or its batteries.

“We’re looking for a miracle now,” said Lemmon.

If Opportunity does – or does not – respond to any of these efforts, the MER ops team will once again consult with their MER Dust Storm Review Board,and Fuk Li at the Mars Program Office at JPL, and then the mission and Mars officials at JPL will meet with those in charge at NASA Headquarters in Washington D.C. It’s ultimately up to NASA of course, and Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA, Thomas Zurbuchen, will make the decision.

“Once we’ve done these Hail Marys though, we will have run out of things to do,” said Squyres. “By the time we get past the middle of February, the rover’s power prospects on Mars will be down and the dust factor is going up. Looking at past Mars years, it’s just going to get worse for more than a year.”

Many of the MER ops teams and Athena Science Team members have already joined or will soon be assigned to other missions. A core group, however, will stay on MER, probably through July, to wrap things up and write up the final mission report as is standard protocol when planetary missions end.

Fifteen years is a long, long lifetime for a robot on Mars, long enough to be the all-time record. Yet, the rover that loves to rove roved for so long and covered so much Martian ground, broke so many records, established so many new ones, uncovered so many scientific discoveries, and sent Mars home in stunning, breathtaking images that somehow look hauntingly familiar, and set the bar so very high for all future Mars robots that it is almost difficult to process that Opportunity may never rove again.

MER team members are, however, confronting reality. “I have ambivalent feelings,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. “It’s been fun. We’ve learned a lot and there’s a lot more to learn if we had an extended mission. On the other hand, life goes on. Right?”

But, it ain’t over ‘til it’s over.

‘We’re going to lose Opportunity some day,” Squyres said, stating the obvious that so many people for so long never really contemplated as obvious. “No matter what happens in the coming weeks, we will be able to say we did everything we could have done. For now we’re going to keep trying until it doesn’t makes sense to do so anymore.”

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth