Planetary Radio • Jun 01, 2022

Planetary Radio Live in London: The Moons Symphony

On This Episode

Ashley Davies

Volcanologist and member of the Europa Clipper science team for Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Amanda Lee Falkenberg

Composer of The Moons Symphony

Mark Sephton

Imperial College London professor, planetary scientist, and Europa Clipper science team member

Linda Spilker

Voyager Mission Project Scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Additional guests include:

- Marin Alsop, conductor for the London Symphony Orchestra’s recording of The Moons Symphony

Host Mat Kaplan has returned from the UK and the recording of The Moons Symphony by the London Symphony Orchestra. You’ll hear excerpts from our Planetary Radio Live show celebrating this intersection of art and science with composer Amanda Lee Falkenberg and three distinguished planetary scientists. It was produced at Imperial College London before a live audience.

Additional Recordings

Complete May 23, 2022 Planetary Radio Live Show

Here's the complete recording of our show created at Imperial College London.

Conversation with Marin Alsop & Amanda Lee Falkenberg at the recording of The Moons Symphony

Our complete conversation with conductor Marin Alsop and Moons Symphony composer Amanda Lee Falkenberg.

Interview with David Alberman, second violin first chair and elected chairman of the London Symphony Orchestra, about The Moons Symphony

In this complete backstage recording of his interview, David tells us about the LSO and its recording of The Moons Symphony.

Nicole Stott addresses the London Symphony Orchestra

The Moons Symphony composer Amanda Lee Falkenberg was advised during the creation of the composition by artist and astronaut Nicole Stott, author of "Back to Earth." Here, Amanda asks Nicole to provide a few words of inspiration to members of the London Symphony Orchestra before it records the climactic seventh movement, inspired by Earth's own Moon.

Related Links

- Moons Symphony composer Amanda Lee Falkenberg’s previous Planetary Radio appearance with astronaut Nicole Stott and Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker

- The Moons Symphony

- The London Symphony Orchestra

- Conductor Marin Alsop

- Imperial College London

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

On the Apollo 11 goodwill messages disc, messages from the leaders of how many countries other than the USA are included?

This Week’s Prize:

That rarest of asteroids, a r-r-r-rubber asteroid.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, June 8 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

Name all the United States planetary spacecraft (those that went beyond Earth orbit) that launched in the 1980s.

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the May 11, 2022 space trivia contest:

Why is there a depiction of a snake on the Perseverance rover?

Answer:

The depiction of a snake as part of the Staff of Asclepius or Aesculapius on the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover honors the healthcare workers who have been on the front line in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Question from the May 18, 2022 space trivia contest:

What Messier catalog object could have been named after a Natalie Portman movie?

Answer:

The Messier catalog object that could have been (but wasn’t) named after a Natalie Portman movie is the Black Swan open cluster, M18.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio Live in London. This week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. I'm back from the United Kingdom, where, in addition to walking about 30 miles, I witnessed the recordings of The Moons Symphony, by world-renowned conductor, Marin Alsop, and the London Symphony Orchestra. You'll hear my conversation with Maestra Alsop and Moons Symphony composer, Amanda Lee Falkenberg. Amanda will then return for highlights of the show we did in front of an enthusiastic audience at Imperial College London. And you'll also hear excerpts from Amanda's magnificent composition. All that, and we'll still announce two winners of Bruce Betts' space trivia contest when we get to What's Up.

Mat Kaplan: The InSight Lander could sure use a housekeeping service, or a convenient pass by a dust devil. Take a look at the dust coating one of its solar panels in the May 27 edition of The Downlink, our free weekly newsletter. It's no wonder the probes days on Mars may be numbered. There's much more at planetary.org/downlink, including a story about NASA's funding for further development of a cool new solar sail design. My wife and I flew to London right after the Humans to Mars Summit in Washington, DC. By the way, I'll feature H2M in next week's show. We barely had time to check into our hotel before we rushed to St. Luke's, the old church that the London Symphony Orchestra has beautifully renovated as its home. The recording of The Moons Symphony was already underway. We and others sat high above the orchestra, afraid to move or make a sound, as the music unfolded beneath us. It was quite a process, with each movement progressing a few measures at a time. Under the watchful eye of composer Amanda Lee Falkenberg, conductor Marin Alsop led the ensemble through all seven movements.

Mat Kaplan: Symphonic portraits of Io, Titan, Enceladus, Miranda, Ganymede, and our own moon. Later, after the musicians had been released for the day, I sat down with Amanda and Marin. My goodness, this was thrilling. Thank you so much to both of you for allowing me to witness this.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Thank you so much for coming over here, Mat, especially with your busy week. It's been extraordinary, the day. And you're right, after living with an electronic score for five years, to have the life breathed into this music is speechless. It was interesting, I didn't know what my reaction was going to be. And little did I realize, I felt I had come home. Magic, absolute magic. And a miracle. I mean, there's just been so many miracles surrounding this project. And Marin, even been involved in this project is a miracle. And then to line up the diaries of LSO, the best orchestra on the planet, with the best conductor on the planet, need I say more. And she's just finessed her brilliance into this day, and it is going to be extraordinary, once we hear the choir laid down with these incredible takes today.

Mat Kaplan: Extraordinary is the word for it, watching this experience, watching you swing that baton and bring this together. Why did you choose to take this on you? You have your choice of orchestras and selections to record and perform?

Marin Alsop: Well, as you very well know, Amanda is an incredibly convincing human being, besides being extremely gifted and talented and a wonderful composer. And every obstacle that we came up against, the reason I was able to get involved really was because of COVID. I had no free time in my diary whatsoever. And then I read her email because I was killing time during COVID like everybody was. And I wrote back to her, and I said, "Oh, what is this project?" And that's how it got started. And then she came to Vienna, and we did a practice trial run with it, see how it went in Vienna, and became fast friends. And I have to say, she also has this great advantage to having a husband, who's also my assistant conductor, who's really helped me with the whole project as well. So it's really a dream project.

Mat Kaplan: I was also struck by exactly that, the collaborative nature of what we saw. I mean, when you record a contemporary piece like this, do you frequently have the composer there to refer to? And we also had that voice of God, happens to be Amanda's husband, who was also helping you to make sure this was exactly right.

Marin Alsop: Well, that's the great luxury, I think, and advantage of doing works by living composers. I mean, it's both the advantage and maybe sometimes the disadvantage, but they can be there and really be part of the process. But Paul's acting more as a producer, saying what we need downstairs, he's listening and using his excellent ears to help in that way. And Amanda's up in the studio with me so that she can help in that. So I really have the best of all possible worlds, so to speak.

Mat Kaplan: What an ensemble. I mean, I couldn't see everyone, but I counted six percussionists, two harps. This is just amazing. And I guess it's what this piece calls for, right Amanda?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Well, we're talking about space, and isn't space pretty epic? And so we need [inaudible 00:05:59].

Mat Kaplan: Space is big.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Space is big. So you can't go short-changing your ensemble, trying to produce an epic piece like this. You call on all forces to get the point across about these fascinating worlds and moons. And especially when you've got a moon like Io, which is the most volcanically active moon in the solar system, you got to pull in all forces you can, to get the message across.

Mat Kaplan: This is a representational piece. I mean, I think of other pieces like Claude Debussy's La Mer, The Sea, even Beethoven.

Marin Alsop: Pastoral.

Mat Kaplan: The Pastoral, absolutely, the 6th. And of course you can't avoid bringing up Gustav Holst, we're in his home nation, The Planets. But The Planets was more of a metaphysical thing, whereas this, if I'm right, Amanda, you were really attempting to capture the true nature of these moons.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: And I'm so much in a more advantageous situation than Holst was. He didn't have the technology a hundred years ago like I have access to, and all these deep space missions that they're achieving and succeeding in getting data back. I'm sure if he was alive right now, he'd probably be doing this sort of thing. So I wanted to capitalize on the advancement of where we are with technology. And like I said, it's a situation where I came across the science and I just couldn't ignore it. And hence why I've employed the choir to sing the science. So this is very much what we call programmatic music, which talks about scenes, and it's very unashamedly telling the story, as opposed to an abstract approach to composing, where you allow the audience to come up with their own story and dialogue. This is very much science driven, so it's like the script to tell the story, which is the science.

Mat Kaplan: I'd hope you can expand on that. I mean, where a piece like this fits into the vast classical repertoire.

Marin Alsop: Well, I think as you so astutely mentioned, that The Planets by Holst, it's probably one of the most popular classical pieces in the repertoire. And yet, it doesn't really represent the planets. It's more about the gods from whom the planets derived their names. And as you said, it's more of a metaphysical than a really science based piece. I think something like this, The Moons Symphony, has a very strong possibility to become part of the repertoire because it also reaches out across disciplines. And it's a piece that we could use in educating kids. We can go out to schools, we can speak to scientists, I mean, I had lunch with an astronaut today. I was pretty excited. And I imagine that the way Amanda could build it out as a complete project for orchestras, it could be very fulfilling and also really establish the piece.

Mat Kaplan: Do you approach a symphony like this as you would any symphony, or is there a different way to approach it because it represents things in the real world?

Marin Alsop: No, I think I approach it the same way. Every piece has a narrative, whether it's a literal narrative or an emotional narrative. And I have to find that narrative. This is easier in a way, because the narrative is clear. But the challenges with this are very different because we have to keep a certain tempo so that we can put the chorus in later. It's a huge orchestra in a big space, and so we have the issues of delay. So it has its own kind of challenges.

Mat Kaplan: Amazing watching this come together. I mean, the quote that I do not want to use, because this is not in sausage in any way, but you don't want to see the sausage being made. I wish everyone listening could have watched this process as it came together, piece by piece, measure by measure. But I'm wondering, how do you do that? When that major component of this Symphony, the choral sections, are not available to you? I mean, how do you prepare it with those in mind?

Marin Alsop: I think it's going to be phenomenal, and actually, it's going to work even better because we have the ability now to mix everything. When you have everyone in one room and you're recording, say, 300 people at once, you can't get separation, so you can't really control things in the mix, as they call it. So I think that this is going to be even more effective and more successful. And I should mention, I'm not sure Amanda knows this, but the boy soloist is the son of the principal bassoonist in the orchestra.

Mat Kaplan: And that's Leo, Amanda?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Of course I knew this because there's a beautiful story built into that bassoon solo because when I found out that Leo, our boy soloist for the 7th movement, his father is a principal bassoonist, I went, "You're kidding me," because in that 7th movement, the bassoon, there's a little bassoon solo that hands off to the boy solo. It's a father.

Marin Alsop: That is freaky. That is freaky.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: The project, this is [inaudible 00:11:12]. So it's like, "Here you go, son, I've set you up, and now the stage is yours."

Marin Alsop: But Dan, who's his dad, was telling me that this is very special also for Leo, because his voice is just about to change. So this is probably the last project he'll be able to sing as a boy soprano. So it's very emotional, yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Do you feel about this ensemble the way we heard Amanda describing it? Obviously it's world class.

Marin Alsop: I think it's a great orchestra, certainly. For me, it's a very personal experience because I first met them with my teacher Leonard Bernstein when he started the Pacific Music Festival in Sapporo, in Japan. And that was 1990, before anyone was born.

Mat Kaplan: I wish.

Marin Alsop: And since then, I've had a relationship with this orchestra and I stepped in the mid nineties. And from then on, I've been with the orchestra every year, every other year. So we have a longstanding history, which is very, very wonderful.

Mat Kaplan: I've only had one experience where I worked with an orchestra on a performance. I had the tremendous honor of narrating the Lincoln Portrait by Copland.

Marin Alsop: Oh, that's great.

Mat Kaplan: And it was the most terrifying thing I have ever done voluntarily in my life. What is the feeling as you go into this kind of a project? Is it the same every time? Is there some anxiousness or is it just the joy of being part of it? Marin, I'll start with you.

Marin Alsop: Well, I mean, I think for someone to be thrown into the deep end, just having to narrate suddenly, I think it could be quite terrifying. But for us, we do this as part of our daily lives, but that doesn't mean that there isn't some anxiety or excitement or nervousness, I think. I would call it more excitement, I don't feel particularly nervous.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: I think the thing that I really celebrate at this situation, with this situation, is that we've got the dream team, basically dictating going forwards, the tempos, the nuances, the characteristics, the sound, the quality, the excellence. And once we get this out there as a recording, it's going to be the benchmark of other orchestras, and to emulate the type of brilliance that is coming from these days recording, and with Marin weaving her magic into all of this, that is what is just worth really the perseverance and the pressure, and just nailing it all, because we know that this is going to be the classic standard moving forwards. And I think that's what's really exciting. And we'll catch our breath at the end of all this.

Marin Alsop: Yeah, we will. We will, for sure. But it's been a wonderful journey. And I think especially today at the recording sessions, to have all of you scientists and explorers with us, it was very moving, not just for me, I think for the musicians too.

Mat Kaplan: What we will talk about on Monday, with a live audience, is this intersection of art and science, that share much more than I think a lot of people realize. I mean, is that something you recognize as well?

Marin Alsop: Oh, absolutely. And I've been very involved with Brian Greene in New York and the World Science. It's just such an opportunity to really link our art forms. I mean, I really believe that science is an art form as well. And what we do is not only an art form, but also a science. So there are lots and lots of crossovers, and each compliments and amplifies the other.

Mat Kaplan: Well said. I cannot wait to hear the end product of this day, and I cannot wait to come back tomorrow and hear the remaining movements recorded in The Moons Symphony. Thank you, both Amanda and Marin.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Well, thank you so much for getting yourself all the way over from the US.

Marin Alsop: It's great.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: And thank you Marin for your absolute [inaudible 00:15:19].

Marin Alsop: My pleasure, you're super.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: To be continued, and yes, and thank you to the scientists as well, and the astronaut the holding the floor for us and just living and breathing and holding their breath, and being statues up there.

Marin Alsop: Yeah, they were great, they were great. Thanks.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Now, at 6:00 PM on Monday, May 23rd, I'm about to begin the first face-to-face Planetary Radio live event since the beginning of the pandemic. Imperial College London had graciously offered to host us. Here are highlights from that more than two-hour celebration of The Moons Symphony. Want to hear it all along with other bonus material? Visit this week's episode page at planetary.org/radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome to Planetary Radio Live in London.

Mat Kaplan: Oh my God, that was so good. We have a wonderful crowd in place in the Clore lecture theater at Imperial College London. I am Mat Kaplan, the host of Planetary Radio, I am thrilled to be here. In fact, I am thrilled to be anywhere in London, in this wonderful city of yours. And as you will hear, it has been especially thrilling to be here over the weekend that we have just completed, for reasons that will become obvious. It is the reason that all of us are here today, all of the people you will meet on our spectacular panel tonight, and hopefully, also responsible for you coming out, as well as we hear about a marvelous new composition, a symphony that you will all have available to you soon, now that it is in the process of being recorded. This is the first live, face-to-face show we have been able to do since the beginning of the nastiness that has been underway the last two and a half years.

Mat Kaplan: So thank you for turning out for that as well. It is such a pleasure to, once again, be in front of an audience. Some of you know the fellow who's coming up next, he is our CEO, and he has a special message for us, which hopefully you'll be able to hear.

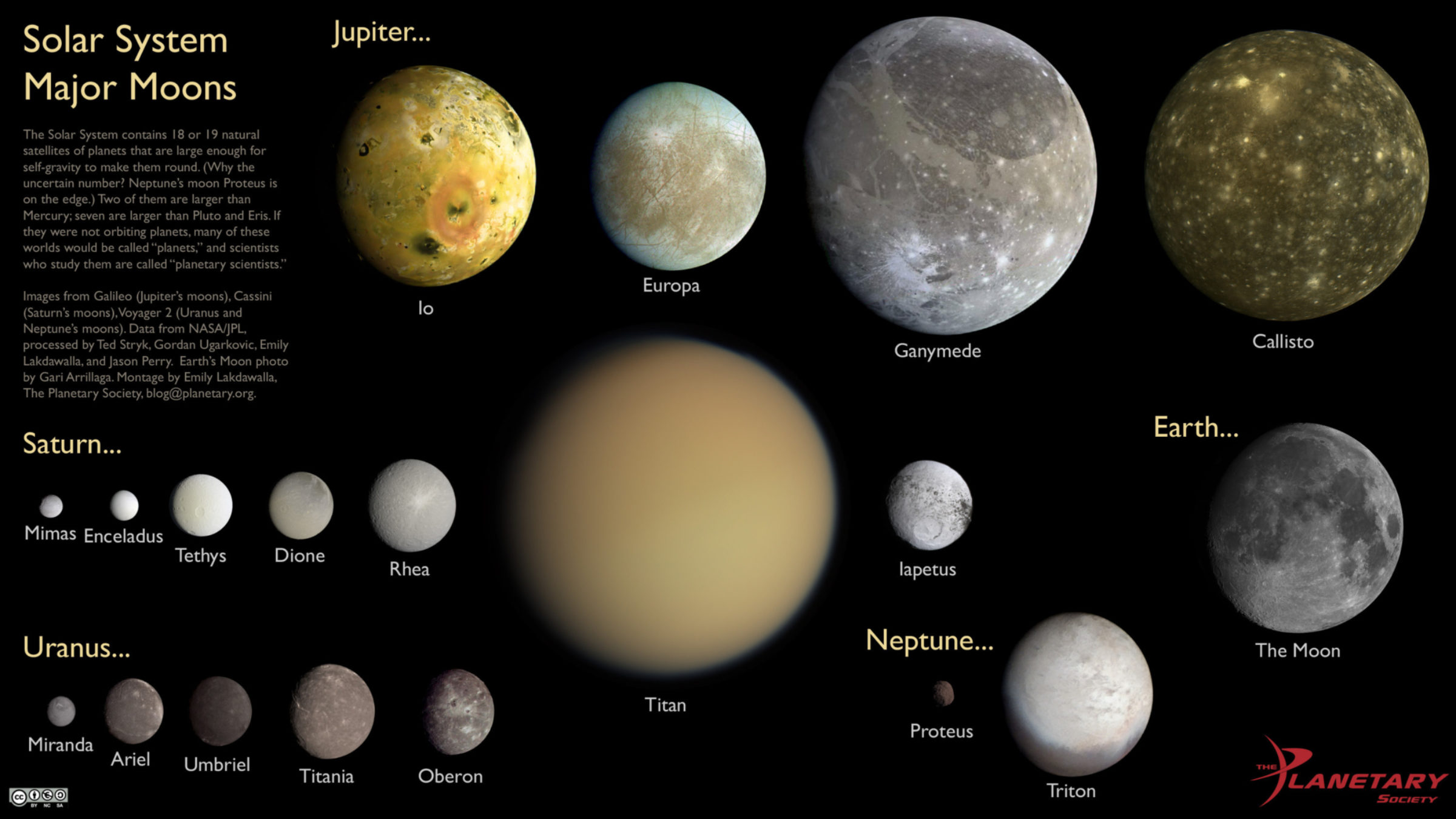

Bill Nye: Greetings Bill Nye here, CEO of The Planetary Society. Welcome. Tonight I join you in celebrating The Moons Symphony, which was composed by Amanda Lee Falkenberg when she was inspired by the science and beauty of the intriguing moons in our solar system. I look forward to hearing the recordings made over the last two days by the London Symphony Orchestra. Tonight, we're joined by members of the orchestra, Ms. Falkenberg herself, The Planetary Society's own, Mat Kaplan, several planetary scientists, and at least one astronaut artist. They will take you to the intersection of art and science in the cosmos. As a very smart man once said, "Scientists are always artists." And who are we to argue with Albert Einstein? Who, along with changing the course of history with these discoveries about the nature of the universe, was a remarkable violinist. Have a wonderful time tonight, check out all we have to offer at planetary.org. And so now take it away, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Bill.

Mat Kaplan: So one bit of unfortunate news, the only unfortunate news I hope I have for you this evening, Nicole Stott, who is in town, our astronaut artist, was around for the recording over the weekend, let us know about three hours ago that she tested positive. So she is not here to join us. She is devastated not to be able to join us tonight. We're going to try and present some of the material that she would've had for you. But to get us back on the happy side of the street, you've already heard her name, she is the reason why we are all here. Please welcome the composer of The Moons Symphony, Amanda Lee Falkenberg. Amanda, come up.

Mat Kaplan: You have treated us to a spectacular weekend. I should say that this started a little over a year ago, when I heard about this new symphony that had seven movements, each of them inspired by a moon in our solar system, from two people independently, Nicole Stott, the astronaut, and Linda Spilker, who we'll be meeting in a few minutes. And I thought, "If those two like it, I better check this out." So we did an online radio interview, I didn't meet Amanda in person until Saturday. It was delightful. And Amanda invited us to participate in upcoming events, including the recording session that just took place. So welcome. And thank you, for I only wish that we could have shared that experience at St. Luke's with everyone here and everyone listening. That was spectacular, wasn't it?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: It was absolutely powerful, magical, and words cannot describe that experience. And this is where I'd love someone like a Nicole Stott to be sitting here next to me, because she has been up in space, she's seen our Planet Earth, united and whole, and she always says to me, "When we come back as astronauts, there's just no word to describe that overwhelming feeling." Well, that is how I felt yesterday, hearing the genius of this orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, birth the music of the Symphony. And so I'm like, "Now, I kind of know how she feels a little bit, actually." So I'm still processing that, okay? So it's still processing, but it was incredible.

Mat Kaplan: And we should say, it's not done. I mean, the orchestra has done its part, but you're going to be where to complete this?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Yeah, we've just come from Abbey Road Studios, the legendary iconic, Abbey Road Studios. And that was my first ever introduction to that magical place. So yes, I have an update. We have had a very great day of progress. We've got through, we've birthed the first three moons, we've identified the most magnificent takes, and we are at [inaudible 00:21:40] right now, I was just telling Linda. And it is sounding phenomenal, absolutely phenomenal. And I know we have a couple members and I just want to say, thank you

Mat Kaplan: Bravo and brava, absolutely. Please, stand up. Stand up, take a bow. No?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Yes. Wow. I mean, we just have the dream team involved. Every aspect of this production, from scientists to musicians, to conductor, to communicators, all of that has just, it's just everything's just been miraculously manifested to bur- All right, okay. [inaudible 00:22:23] later. And it's just, serendipity has been always at the center, just this project's just taken on a life of its own and dictated events that I never foresaw at all, and I'm just going with the ride, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: She's doing much, much more than that. You mentioned the conductor. You could not have done any better, please.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Oh my goodness. Okay, so we literally have the most world famous female conductor walking this planet, and I've only ever identified this incredible woman, Marin Alsop. I don't know if many of you have ever seen her perform. And in fact, she just performed at Southbank Centre, the Shostakovich, to a standing ovation. It was an incredible, powerful performance she gave. And equally, she gave that performance, as you saw, and you witnessed, it's a big work. This is 47, 50 minutes of music. And it's not for the faint-hearted to get up there. I mean, it packs a punch. And we were talking about some of the most volcanically active moons of our solar system. You can't have placid music for that kind of stuff. So we put her through paces a bit and I'm sure she slept very well last night. But she was absolutely magic. And the feedback that I've got from musicians is just that, I mean, she's one with her musicians. I mean, if you're going to have equivalent to the Gene Kranz of Mission Control, that's our Marin Alsop.

Mat Kaplan: And she would've been with us tonight, but she jetted off to Vienna immediately after the recording session. If this evening has a theme other than the Symphony itself, it is this intersection of art and science, which you also heard Bill and I talk about. This is also where I would have been bringing out Nicole Stott, who is, as you've heard, not just in astronaut, who spent two long stays on the International Space Station, but an artist, a working professional artist, and someone who is deeply committed to the welfare of humankind, which certainly includes the arts. How did you connect with Nicole? How did she become part of this?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Oh gosh. I mean, she uses the word awesome a lot, I use the word serendipitous a lot. And we know that and we recognize that, but it truly was very serendipitous. I think just if I may back up, when I'd shortlisted my moons, it was only ever going to be six, you see? And when I was in the middle of writing moon Miranda, which was about the fourth moon I was composing, I remember just this uneasy feeling just creeping over me, and couldn't put my finger on it. And I remember saying to my husband, "I don't know, something doesn't feel right about the structure of this symphony." And one day I was literally in...

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: ... structure of the symphony. And one day I was literally in my studio and really almost finished writing the music, and then it was so intense what I was writing, and I all of a sudden just felt like, "I want to get out of here." And I just beamed myself back to earth, I'm like, "Whoa, it's safe here. That was a bit scary, hanging out there with Miranda." And then all of a sudden like, "Oh, my goodness, I know what was missing. Earth Moon, that's what is missing in this symphony." And I thought, "What if we put the Earth Moon in the symphony and have us standing on its surface, looking down onto this incredible planet that does contain life, it's teaming with possibilities, it's a gift to us all to even exist. We've been traveling to these moons, there's no second genesis if life, at the moment, they found. And it also-

Mat Kaplan: So far.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: ... Miranda shows the violent, harsh edges of the solar system. We've got the Goldilock zone here. And so I felt that was the answer and it just became crystal clear to me, and then Seven Moons was born and, of course, it's a very spiritual number, it's a special number and it just felt I found. So, Miranda was very special to me because it helped me recognize that that was the final story that needed to be told.

Mat Kaplan: So, we have four movements that we will be hearing excerpts from. The climactic one is the Seventh Movement, the one that is inspired by our own lovely moon, which if you dive into it a little bit you may learn that is very likely responsible for life on earth, so we can be very grateful when we look up. Like so many of the people who have looked down on our beautiful pale blue dot from above, not a dot to them but still a world without borders. They get to enjoy what is called the overview effect. I think I've come as close to experiencing it as anybody can here on earth, your music I think is going to help a lot more people get a sense of it.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Well, I think if we're going to use the word overview effect there's a name that we need to mention, of course, that's Frank White.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely, yes.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: And his incredible contribution to the psychological, the spiritual aspect of that life-changing experience, and that's as Nicole. They're so grateful for what he's doing here to help communicate their experience and try and formulate words or concepts so all f us can try and understand what these privileged space crew have experienced, and have more of a deeper profound appreciation for what they're trying to communicate. I love how Frank White said, "We can estimate how this earth rise image is having a powerful, is penetrating the arts and other mediums that we are yet to realize." Well, the Seventh Movement of this symphony is absolutely my personal way of expressing that earth rise. See that whole image I actually had in my studio 24\7 when I was composing every inch of that music, that was my way of being a Frank White, as a musician, to try and communicate that experience that astronauts have.

Mat Kaplan: All right, I want to bring up now somebody who has been part of the Voyager Mission, those emissaries to the stars, Voyager 1 and 2. Maybe not quite from the start of Voyager but was part of Voyager, left it to become the project scientist of the spectacular Cassini mission, which now has completed its mission of revelation of Saturn and is now back to being on the Voyager mission as well, the [inaudible 00:28:46] project scientist for Voyager. Please welcome, from the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, Linda Spilker. So, Linda, I got all that right, Voyager 2 still going strong. It's Voyager 1 maybe that's having a little difficulty right now?

Linda Spilker: Yeah, Mat, Voyager 2 is going strong, so is Voyager 1. We're still getting back good science and the pointing looks really good, but some of the engineering data for the attitude control system looks a little strange. So, we're trying to figure out what exactly is going on. Here's a space craft, a Para space craft that were designed to last four years, to fly by Jupiter and Saturn. And it's been almost 45 years, 10 times longer than their designed lifetime. Every yer we have four Watts less power, we use the decay of plutonium to generate heat, and that runs the space craft. And so every year we have to carefully agonize, "What do we turn off? What's left to turn off?"

Mat Kaplan: Tell me how the two of you connected over the moon symphony.

Linda Spilker: Well, Amanda, you want to start with Bob Pappalardo reaching out to you?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Yeah, so about three months into my research of Moon Europa I kept coming across a particular individual and I'm like, "This guy looks really interesting to me." And I researched him and I'm, "Ha, he's at NASA JPL." And I'm like, "Ha, I'm just going to email him about my project." And so I did, I just set a simple project about my vision about these moons and how would love a world premier in Royal Albert Hall, just down the road, because I wanted to speak with someone to help me anchor the science of these moons and accuracy.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: And so it turns out he was lead scientist for the Europa Clipper mission and he wrote back to me about seven days later, and agreed to Skype, and so we chatted about the characteristics of Moon Europa and the mission. And he was very interested in my project and he said, "I think the scientists would be interested in your symphony too, Amanda." I'm like, "Really?" He said, "Oh, yes." And he mentioned Linda Spilker, and that's who connected us to the project.

Linda Spilker: Hearing about the project I was very excited to take the moons and actually put them together with music in a way that the public could relate to. And so I invited Amanda to come to one of project science group meetings, and talk a little bit about her symphony and play some of the Music. And from then on we've been communicating and working on the science for this particular symphony.

Mat Kaplan: Thank goodness. Linda's accompanied by her husband, Tom Spilker, who is as experienced, stand up Tom, at JPL. Another very accomplished scientist and engineer, because now he's figuring out how to build us a space station worthy of what you saw in 2001. I don't know about you but I want a visit. Linda, address, just very quickly, how cameras not just have connected us to these missions y delivering these beautiful images but to the science as well.

Linda Spilker: Well, it's so incredible, these missions when we go out we were thinking, "Okay, the moons for these outer planets, they're going to look like our moon." That's what we have for a model, they're going to be old and heavily cratered, and so we go out with Voyager, we get to the Jupiter system. The first moon, Callisto, is cratered, and then as we go closer and closer our paradigm totally shifted. Look, no craters, this looks fractures. Europa, it looks like an ice ball, what happened? And then of course Io with volcanoes. And so the journey continued, each moon in the solar system has a unique personality, unique characteristics. You can look at a picture of a moon in the solar system and say, "I know which moon that is."

Mat Kaplan: And thank goodness, because otherwise the symphony would've had one movement. We're going to get into the symphony now by introducing you to four of the moons, and therefore four of the movements, and we'll mention the moons represented in the other movements in the symphony. But before we hear those excerpts we do want to hear about the first of the moons in the first movement, the moon Io, look at that horror of a moon. And to help us learn about it one of the world's foremost experts on that moon and on volcanology in general, he is yet another representative of the wonderful Jet Propulsion Lab, but I think you may recognize his accent as making him a local here, or somewhat of a local. Please welcome up, here he is, Europa Clipper Science Team member, also the author of that book you saw a few moments ago, Volcanism on Io, Please welcome Ashley Davies. So, Ashley, where does this little horror show of a moon rank in your list of favorite, your top 10?

Ashley Davies: Actually it's my first and second favorite moon. I got interested in volcanology right back in the days of Voyager when I was in high school when Voyager sent back the first images of these huge eruptions taking place on Io, I thought, "That's interesting, that's unexpected." I was kind of an astronomy geek, even back then. This was a revelation, it shook the world of planetary science, it shook the world of science. At the same time, give or take a few months, there was a big eruption in America at Mount St. Helens and I thought, "ooh, volcanoes. These sound interesting." I didn't have the patience to be a sedimentologist, so this is something a lot more immediate, a lot more interesting and-

Mat Kaplan: Certainly more dynamic.

Ashley Davies: Certainly, very dynamic indeed. There are 250, this is what we knew in 2015, erupting or recently erupting centers on Io. Io is the most volcanically active, one of the most dynamic bodies in the solar system, the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Since then, since 2015 we found about another 40 or 50 new sites of volcanic activity mostly from ground-based telescopes equipped with adaptive optics. And what we're looking at are the styles of volcanic activity, and using Io as a way of looking back into earth's past and into the past histories of the terrestrial planets, because the type of eruptions on Io, the styles of eruptions on Io once helped shape the terrestrial planets and the moon. This was in their distant pasts and we see the remnants of these eruptions, but ow we can go to Io and see these happening right now. At the same time we go to volcanoes on earth, we study how volcanic eruptions behave on earth and we apply that to understanding what's happening on Io.

Mat Kaplan: And this is one of the most important themes that we try to communicate to people at the planetary society. We study other worlds in part to learn about our own.

Ashley Davies: Right, the surface of the moon, the surface of Mars. Earth have these huge fields of lava, we didn't know a lot about how they were placed but we can see eruptions of similar styles taking place in Io now, so Io is a great template for looking back into the past, geological history of earth and other places. And one of the glories of this is that just before Voyager 1 reached Io, some scientists published a paper which said that, "We've looked at the dynamics of the Jovian System and we've looked at the fact that Io and Europa and Ganymede are locked into this orbital resonance; and we think that this could generate a lot of internal heating so, who knows, there might actually be some volcanoes there." It was the best timed paper in planetary science history, because just a few months later those volcanoes were found on Io. And this just changed our understanding of how the whole solar system works, it changed our paradigm for where life could exist. Not on Io but on some real estate quite close by to it. And it was just a game changer, and that's just one of the gloriest legacies of Voyager.

Mat Kaplan: And when you mention this resonance to the orchestra yesterday, what struck me is resonance, the music of the spheres, Amanda, music.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Absolutely, and I think I had the privilege of when I was invited to the Cassini scientist meeting, I had the opportunity to consult institute with Dr. Ashley Davies on the volcanic world of Io. And basically what he's just described is the paradigm shift and all these important things about orbital resonance, I'm like, "Right, this needs to go in the symphony." And I initially hadn't planned on putting Moon Io first but I've realized I double things around and I went, "Hang on, this is a really good opportunity to set the stage for the concepts that are going to be applied with the other moons, but to a lesser degree." So, I think, having Io positioned first really does get across the idea of this gravitational tug of war that is just the most extreme run away of title [inaudible 00:38:09] that doesn't exist on the other moons, but there's a similar exchange, and so I thought, "No, by the way, I think we just need to begin the symphony with a blast. So, why not we just choose Io to start this galactic whatever symphony tour."

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Yeah, so I felt like we need to put that first, and to really help get across this message it was a paradigm shift. All of a sudden the new Goldilock zone occurred away from the earth-centric planet earth, and I think these things are really important when we start traveling beyond the asteroid belt because this is why this moon symphony exist, because there are a fascinating world out there.

Mat Kaplan: Amanda, we are finally ready to hear the first of those excerpts. Io, the first movement, I'd only hear d this version of course until the weekend, and it sounded just fine. But then you hear it from a symphony orchestra, how was this created?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Fortunately technology In the music sector, this was using synthesized software to produce the sounds of a orchestra to emulate the ideas that I wanted to convey when the moment would arrive, when I'd have the real orchestra to play the music. And fortunately the technology is fantastic, I think it does a really good job of communicating your ideas. Choir, not so much, but fortunately that's going to be changing next weekend, but you're hearing what we call a synthesized, computer generated version of a symphony orchestra.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: (singing)

Mat Kaplan: So, wait until you hear it from the London Symphony Orchestra and from the choir that is in the process of being recorded at Abby Road, I cannot wait. We're going to go on to another moon, it's one that you've already heard mentioned, that's the Europe Clipper mission which is under construction now. I hear it's going very well at JPL, these things take time and sometimes a few extra dollars but this is the mission that will fly out to Europa and, hopefully, be able to find some stuff to fly through emanating from that world. One of the reasons we're so curious, of course, about Europa is this possibility that it could be a place to find life. Whether it will be life like us or something completely different, no one knows, we won't know until we go and sniff it out.

Mat Kaplan: To help us explore that, help us welcome Imperial College London's own Professor Mark Sephton. Mark, come on up. Mark, you are also on the Europa Clipper team, right?

Mark Sephton: I am, I sat next to Ashley and we're both sat together on the Europa Clipper mission.

Mat Kaplan: Did I get it right, Bob Pappalardo is not here for us to ask, are things coming along?

Mark Sephton: Yeah.

Ashley Davies: Absolutely.

Mark Sephton: Of course, yeah.

Ashley Davies: Yeah, the bits of [inaudible 00:44:21] at JPL being bolted onto the space craft, propulsion module was due to be delivered just last week, the space craft is coming together.

Mat Kaplan: Humans are not likely to go there any time soon, it's not a nice place to be a human, at least not on the surface. Mark, you're the astrobiologist among us.

Mark Sephton: I think that's right but the majority of our exploration of the solar system, from astrobiological point of view, is really looking for evidence of life in any form and life is most likely to be in microbial form. Microbes dominated the earth throughout history, we're just the last tick of the clock in the day of earth's history. So, microbial life is the most we could possibly hope for.

Mat Kaplan: Probably not on the surface because that is made a very nasty place by Jupiter, Linda?

Linda Spilker: Yes, the radiation coming from Jupiter is very intense. And so if you're on the surface of Europa it'd be very dangerous for you as a human, you wouldn't last very long even in a space suite. But there's this thick layer of ice that's basically covering over that ocean underneath, and that's where we might find life.

Mat Kaplan: What are we looking at n this incredibly complex surface?

Ashley Davies: Well, the same title forces that affect Io also affect Europa to a lesser extent. So, there's a lot of stresses that build up in this ice shell which cracks. What we see here is the result of intersecting stress, fractures and stress patterns shattering the surface, if you like, of Europa. We know that it's a young surface because there aren't that many impact craters, impact craters dominate the surfaces of most other bodies in the solar system. Io doesn't have any impact craters at all because there's so many volcanic [inaudible 00:46:15] taking place which erases them just as they're created.

Ashley Davies: On Europa there are few impact craters which point to a young surface, this is why it's so intriguing to go there and so interesting to go there. The possibility that there is plume activity on areas where there's been recently surfacing means that the radiation that's just been mentioned hasn't had a lot of time to degrade what's been brought to the surface. And so, one of the things that Europa Clipper will do, one of the things that the instrument that Mark is working on will do, will be to look for this new material, and that will show us what's actually making up the crust, and anything that might be coming through from the oceans. Looking for the chemical fingerprints of this material.

Mat Kaplan: So tough on the surface but, Mark, as we heard Linda say, we now know, there really isn't much question left, is there, that there is this warm, probably salty ocean that is protected by the ice, it's a radiation shield.

Mark Sephton: Yeah, the subset environment is where we're most likely to have habitable conditions.

Mat Kaplan: We are ready to hear the second excerpt now from the second movement, Amanda. What struck you, what inspired you to create this movement about this moon?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Well, it's interesting because Linda was talking about how they were discussion whether they should have a camera on board, the Voyager space crafts. Well, I think there's a compelling story about Dr. Margaret Kivelson and the magnetometer, and you almost cannot talk about Moon Europa without mentioning that magnificent instrument which detected the sub-surface salty ocean, which is critical for the idea of potential microbial life. This particular moon and at least the lyrics, there's a lot of question marks because there's a lot of questions that needs to be answered, and that's what this whole mission is devoted to, this flagship mission. Of course that inspired me, and the plume activity that's always been very compelling, it's Europa's sub-surface trying to communicate to the scientists being very, as I said before, as opposed to Enceladus which is gushing all this information, free samples for space crafts to fly though.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Europa's been a little bit cheeky and tantalizes the scientists a little bit more, so it's not as giving as beautiful Enceladus. And so I play into the drama of that, and also there's sort of a determinations element in the atmosphere in the music because NASA is so keen for these answers to be solved, and so I wanted to play into those themes.

Mat Kaplan: Without further a due, here is just a portion of the second movement of the moon symphony, Europa.

Mat Kaplan: (singing)

Speaker 1: I noticed my foot starts tapping again. My head is bobbing. You should have seen me over the weekend, with the rest of us, just so inspired.

Speaker 1: We will only have time for samples of four movements tonight. And if there's one I regret not bringing you, Titan, that big moon of Saturn which is somewhat less mysterious than it used to be, largely thanks to your mission, Linda, the entire Cassini team. Tell us a little bit about this moon.

Linda Spilker: Well, Cassini spent 13 years in orbit around Saturn. And this giant moon, Titan, it looks like a golden haze and shrouded world. We couldn't see through to the surface with Voyager. And so that motivated us to go back, carrying a Huygens probe, a probe provided by ESA, to parachute down to the surface of Titan with cameras and instruments to really reveal, for the first time, what did that surface look like?

Linda Spilker: Titan's about the size of the planet, Mercury. We used it as a tour engine, so we flew by over 125 times, very close to Titan. And what we found was a surprisingly Earth-like world. Here's a world where methane plays the role on Titan that liquid water plays here on the earth. Methane can form clouds. It rains methane on Titan. It can freeze. So it's just at that triple point, that right temperature, to be in all three states.

Linda Spilker: And so when you look at the surface, of course, it's sculpted by the methane rain. At the North Pole there are giant lakes and seas; not of water, but of liquid methane. Methane is the gas in your stove. And here it is, it's so cold, it's actually a liquid. And you can see the tributaries and the rivers, channels flowing into this lake. Can see also giant mountains, ice mountains. Ice is the rock of the outer solar system. And maybe we're getting, with the liquid water, organics coming out as well, that Titan is just full of organic material. Dunes at the equator. Particles form high up in the atmosphere as methane is broken apart. You pick off one of the hydrogen molecules and you can grow longer and longer chains of organics. And these can fall to the surface and form dunes.

Linda Spilker: We landed in what appears to be a dry riverbed. You can see rounded icy pebbles, that methane has flowed through this dry riverbed rounding those icy pebbles. So we landed softly on the surface. Huygens probe sent the data to Cassini. And all of these wonderful pictures came back. And in fact, when we reconstructed, on the surface we could actually see the shadow of the parachute from Huygens fall to the surface.

Linda Spilker: So an intriguing world, huge thick atmosphere; mostly nitrogen, but lots and lots of organics. So we wonder, could you have life, very different from Earth life, in that liquid methane on the surface of Titan?

Speaker 1: So Mark, I'm going to go to you in a moment to talk about that possibility, and would it be life as we do not know it. And by the way, Huygens, from the European Space Agency, a tremendous success by that agency that has had so many wonderful missions.

Speaker 1: Mark, life as we would not know it, right? There are people looking into this.

Mark Sephton: Yeah. One thing that's for certain, one of those raw material ingredients is certainly present: hydrocarbons. Ashley's a volcanologist, and I spent my career study in organic matter. I wonder if we both died and went to heaven, you'd wake up in Io and I'd wake up on Titan.

Ashley Davies: All right. Right. Yep.

Mark Sephton: But even at the most conservative thought about Titan, it represents a hydrocarbon-rich world, it can tell us something about the chemical steps towards life. So astrobiology is not just about detecting life, it's about understanding how life could originate, has progressed, and then sometimes gone the full distance and actually generated a living organism.

Mark Sephton: So, to use a London Underground analogy: if life starts at Baker Street and needs to go all the way to the end of the line, but gets off at St. Pancras, we want to know why. So Titan may be an environment in which we can look at the first chemical steps towards life, because we know the ingredients are present, and see how things have evolved.

Speaker 1: We could spend this entire evening talking just about this moon, or any of the others that are covered by the seven movements. But Linda, because your spacecraft revealed it, what are we looking at here?

Linda Spilker: This is the moon, Enceladus. Enceladus is tiny compared to the other moons we've talked about. It's about 1/10 the size of Titan, it's about 500 kilometers in diameter; could fit nicely across the UK. And it's a tiny world we expected to be completely frozen. And instead, Cassini found that those are the blueish features there, we nicknamed them tiger stripes. Out of those come hundreds of individual jets of material, forming a giant plume. There's a global ocean underneath the surface of Enceladus. What a surprise. A tiny moon should be frozen solid. And yet this tidal interaction, these resonances, also work at Enceladus.

Linda Spilker: So this is calling for a mission to go back. We have a 10 year plan for NASA called the decadal survey. And the second of these big missions is a mission to go back to Enceladus with something called an Orbilander. It would orbit Enceladus, make measurements, and then take the whole spacecraft down to the surface of Enceladus to make measurements, probably right there at the South Pole, close to one of these jets, and make measurements. In fact, you could imagine putting your hand out, putting out a sensor to collect those particles falling like snow, bringing it back in and then doing the analysis. And you aren't going at these high speeds, you've got these great, very sophisticated instruments. Who knows what we might find.

Speaker 1: Amanda, I think that your coining of the phrase free samples is going to be adopted by the entire scientific community now. This inspired the fourth movement in The Moons Symphony, a lot of what we've just been hearing about, right? This possibility, this tantalizing possibility that we may just find that we're not alone.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Yeah, exactly. And what I felt so much about this particular movement is the romance of these outer solar system domains. Not only partly because Enceladus happens to be part of a very beautiful planetary system called Saturn, of course, the beauty pageant of the outer solar system, the winner of that. But not only that, I mean, just how romantic, if we could transport ourselves to the surface of Enceladus and see ... geysers on earth can be breathtaking enough, but imagine standing on Enceladus with these geysers that are watery towers of fountains, emulating tens of thousands of kilometers into the night sky and actually formed the E ring of Saturn.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: And if that wasn't breathtaking enough, you have Saturn in the backdrop, accompanying this dreamy scene. I think this is to my point, this is not sci-fi, this is sci-fact. This is actual events happening in our outer solar system. So that's what I was really wanting to go after, the romance and the beauty of this experience. And that's what this movement explores.

Speaker 1: So let's hear just a portion of the fourth movement of The Moons Symphony.

Speaker 1: Breathtaking music. Breathtaking music for a breathtaking world. We go on now to two more moons, they represent the fifth and sixth movements in The Moons Symphony. This strange little rock is called Miranda, which I assume you chose not because its name is similar to yours?

Marin Alsop: No.

Speaker 1: But because it's ... well, gentlemen, it's kind of a weirdo, isn't it? Ashley? I mean, just geologically, this is a strange place.

Ashley Davies: Yeah. It's a moon of Uranus. This was observed by Voyager on a flyby, so we've already seen one half of it. It looks as if the moon is being smashed apart, and it just sort of smashed itself back together again. Some other internal process might have caused this, but there's really a lot about it we don't know. One of the mysteries of the outer solar system.

Ashley Davies: It's interesting that this ties now into this decadal survey which has just been released. The highest priority, from the science community, is to send a new mission back to the outer solar system. It's about time too, to go to Uranus, and explore Uranus, and explore the moons of Uranus. And include getting an image of the other side of this thing. We've only seen half of it, so it's really intriguing to know what the other half looks like.

Speaker 1: We should clarify, the decadal survey, made with these recommendations made that do guide a lot of planetary science in the years to come ... decadal, 10 years, ends up being even more than that ... the number one recommendation for a new mission is a Uranus orbiter. But the top recommendation is to get those samples back to Mars, which we've been working on for so many years. And that is quite a distraction from exploring many other parts of the solar system. So we're hoping that NASA will be able to accomplish all of these things.

Speaker 1: I've talk to so many scientists who have been saying, "Ice giants, we must visit the ice giants; Uranus and Neptune," because not only are they fascinating in themselves, but they represent many of the worlds that we are seeing circling other stars, right, exoplanets?

Linda Spilker: That's right.

Ashley Davies: Yeah. Yep. Absolutely. I'm hoping that we see planets in resonances. And some of them are probably volcanic. We've seen planets which might have magma oceans on the surface. We see planets in orbital resonances. And you cannot help but think, "I wonder if they have volcanoes there?"

Ashley Davies: And again, volcanism is a vital process in the evolution of planets. I think it's just a matter of time before we really start to nail down just how many of these worlds out there, these thousands of exoplanets that are being found, are indeed actually volcanically active.

Linda Spilker: And ice giants are interesting because so many of the exoplanets we've found fall in that size range, about the size of a Uranus or a Neptune. And so, by studying these worlds in our own solar system, we're getting clues about what these other exoplanets might be like as well.

Linda Spilker: And then the Uranus mission also is carrying a probe. And that probe is to go into the atmosphere of the planet itself, and that you'll start to make comparisons. The Galileo probe at Jupiter, now you'll have a Uranus probe as well.

Speaker 1: Something to look forward to. It's many years off, but thank goodness it's now maybe coming into the pipeline.

Speaker 1: We are going to give this next moon very short shrift, which we shouldn't because it's a big moon. Ganymede, that Amanda turned into the sixth movement of The Moons Symphony.

Ashley Davies: Well, Ganymede is the biggest moon in the solar system. It is caught in the same resonance that drives activity on Io, and likely within Europa. It almost certainly has an ocean underneath an icy crust. It has a magnetic field, which is very unusual for these moons. And that tells us something about the interior structure and the interior composition. It also has a surface which has been torn apart in places and reformed. It's got a very interesting geomorphology, or morphology. And there's a lot about it we don't know.

Ashley Davies: And the interesting thing, or the exciting thing, is that NASA is building Europa Clipper to go and study Europa. European Space Agency is building a mission, right as we speak, called the Jupiter System IC Satellite ... it's called JUICE.

Speaker 1: JUICE. Yes.

Ashley Davies: I can't remember. I admit it, I can't remember what the acronym stands for. It's called JUICE. And it's going to be basically-

Speaker 1: Jupiter Icy ... Oh God no, I [inaudible 01:07:33]-

Ashley Davies: There we go. Let's not go there. Yes, it's called JUICE. And it's going to study Ganymede and Callisto, the outermost of the four large Galilean satellites. There's going to be some overlap with Europa Clipper. Which is great, it's going to be a really exciting time to be in planetary science. I can't wait for all this to happen.

Speaker 1: What intrigued you, Amanda? Why? There are so many other moons to choose from too.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Well, okay, so it's the biggest moon in the solar system, that was a bit of a hands down. But the magnetic field really intrigued me because the science that it's offering to scientists, as a laboratory to learn more about other magnetic fields. Because it is embedded in Jupiter's own magnetosphere, and these conditions protect us from the solar winds.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: At the second half I wanted to just change the format for this last of the science moons, if you like, and pay tribute to our Galileo Galilei, the discoverer of all these Galilean moons back in 1610. So the second half is very celebratory, saluting him, the father of modern science, and his colossal discoveries back in 1610 with his handheld telescope. And wow, what if he lived in our times right now? So I wanted to give him justice and give him a voice in this moon.

Speaker 1: I should say, that if you go to The Moons Symphony website, you can hear all seven of these synthesized versions of the movements. But when that recording comes out, and, fingers crossed, when it appears across the street at the Royal Albert Hall, being performed by the LSO or some other equally wonderful ensemble, well, I hope I can be there.

Speaker 1: Let's go on to the last moon, the seventh movement in The Moons Symphony. Do you recognize it? Who knows? Yell it out. No scientists allowed. Yes, Bill.

Bill: The moon.

Speaker 1: That's our moon. That's right. This is the far side, not the dark side. Correct people if they say that. It's the far side of the moon, now being revealed to us, well, in part, by the Chinese, by Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, American orbiter, and many other spacecraft that are headed there, if they're not already there.

Speaker 1: Gosh, I think, Amanda, introduce us to this climactic seventh movement because we're ready to hear it.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Yeah. So where's Nicole right now, really?

Speaker 1: Oh, I know. Yeah.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: But it tells a very simple story. It starts with a boy's solo ... which I would like to expand on a little later ... which is the first time in the symphony that introduces the sound of a solo boy's voice. Which does two things, it represents the fragility of Earth and also the children of our future. But soon, the boy's solo is joined by a full choir to represent that the children of this earth are not alone in these planetary plights. And as a united species, we will solve the problems together.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: So this synopsis is what is really the basis of this seventh moon. And I do want to share something really beautiful that has happened, again, very serendipitously. The LSO's principal bassoonist happened to be the father of the young boy's solo, who is here tonight. And Leo Jemison will be our boy soloist for the seventh movement. His father has played ... now I can say it in past tense ... the bassoon part.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: And I think what just blew my mind, when I heard this ... I don't know if the excerpts going to do this tonight ... but just before the boy's solo begins there's this delicate little bassoon solo that segues into the solo for the boy's voice. And of course, it's his father playing that bassoon and he's about to sing the solo on stage. And you can imagine that, for a son that age and a father to be involved in a project like that, for me, I can imagine it's kind of rare. And yet, here it is, showing up in The Moons Symphony, of all the times that it was ever going to have a story, a backstory, well, this is The Moons Symphony.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: So he's here tonight, our Leo Jemison, and-

Speaker 1: Leo, please take a bow.

Speaker 1: Now, what we're about to hear, this is not Leo, right?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: No.

Speaker 1: But recording tomorrow?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: No. Well, next Saturday, the 4th of June. And Joshua Abrams was our original vocalist who sung three years ago. And I should also point out that the vocals that you are hearing, that was an experiment that happened through COVID. We wanted to replace the synthesized choral samples. So we hired 12 vocalists from the London Voices, in lockdown, to sing in their individual studios, and then send them to us in Dubai to mix down and present some type of COVID choir, I call it. So it's not mixed as an ensemble, because it was impossible during COVID, but at least we could understand the libretto that way.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: So the two soloists, Daniel Koek who will be singing at Abbey Rose Studios is the tenor soloist you'll hear, with [inaudible 01:12:45] here in London. So these two artists we recorded back in 2019. We will be having the full session with a 60 voice choir. I've been told today, actually, Ben Parry, who's our conductor, next weekend those 12 COVID choir candidates will actually be part of the 60 voice ensemble.

Speaker 1: Wonderful.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: So there's a beautiful backstory just there, and finally reunited and whole again. So that's pretty much the story of the seventh movement.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know about the rest of you who were there yesterday at St. Luke's. I was in tears and got goosebumps again today, and felt it's overpowering. Simply beautiful. I have to say it again, you must hear it as performed by the London Symphony Orchestra as soon as it becomes available. Were you as thrilled as the rest of us?

Speaker 2: Oh, look, it was the moment. Obviously I was quite critical with the score and following all the detail. But Marin Alsop gave us quite a longer take with this Moon. Obviously we're working in little sections. There's a lot of material to get through. And this Moon is a little bit easier musically to pull off. The story's a little more simple and it's much more lyrical. And there was a point where she just allowed the London Symphony Orchestra to play their hearts out. We had probably four minutes to the end where they just sawed on their instruments. I was told there was not a dry eye in the house, and I got quite emotional on stage with Nicole and yourself and Chris [Bake 01:17:21]. I wrote something on social media today and my comment was, they played as though they were on that surface of Earth Moon, beaming that experience through musical vibration from their glorious gifts as artists, back here on planet earth. I never thought I would have that analogy, but that's what they gifted us yesterday.

Speaker 2: I think that was just such a powerful moment in the whole experience of St. Luke's and this musical recording. So I was blown away.

Mat Kaplan: It was an absolutely stunning end to the sequence of movements.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: Right. And for me, Mat, almost I could picture the earth there. It's this small, complete planet, as Nicole would say. In the sense of longing to take care of this planet. Very powerful.

Mat Kaplan: Mark, you were there.

Mark Sephton: Yeah. Very impactful emotionally. I felt like I've been beaten up with an emotional baseball bat by the end of it. But goosebumps upon goosebumps, to see the orchestra, one big human machine producing something so coordinated and harmonious and wonderful, it's very, very emotional. It was overpowering for me. I found it quite dramatic.

Speaker 3: Which is a good term.

Mat Kaplan: Taking us back to the theme of the evening, which is this intersection of art and science ... which I hope you agree, we have beautifully illustrated this evening. The line I came up with was, here it is; that great science inspires great art. Great art can be the highest expression of scientific wonder. Am I off base, Amanda, or does that sound right to you?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: I think being a film composer and knowing the power of music to tell stories, the persuasive language of music to manipulate emotions, that is when I saw these Moons and I instantly thought, they need music. They need emotion. It's only when I started investigating them that I came across all this incredible science. That's when I thought, wow, there is an opportunity that cannot be missed here. And that's when I thought, what about if I employ the forces of a choir to sing the science? It's going to give it so much more outreach and meaning, and we'll be able to communicate more of its story. And that's when the project started to grow in size and scope. I just thought, wow, this is so intriguing to me. I'm a teacher at heart so I'm always wanting ... I'm very curious about life and learning. I just thought that here's an opportunity to team science up with stories, with space, but with the universal language of music, which communicates to all of us.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: And space is for all of us as well, and science should also be that, and funny enough, Marin Alsop's music should be for everyone. So it's just a really beautiful global collaborative spirit that just engages all these worlds that overlap. And to me, that is the essence of this experience. That's the main symphony.

Bruce Betts: I have mentioned this before, I am a big fan of Walt Whitman. I love Leaves of Grass. He wrote a poem in there called The Learn'd Astronomer. He was dead wrong. He basically is saying, oh, these astronomers, they're all about the numbers and analyzing and this. They don't feel the romance. And Walt goes out and he looks up at the moon and the sky and he feels it. Well, he was wrong, right, Linda?

Linda Spilker: Absolutely, definitely. The feeling coming through and [Saladis 01:20:45] of course is one of my favorite movements. But actually being able to feel like I was there, watching those rows and rows and rows of jets going off in Saladis and those plumes.

Ashley Davies: I appreciate the effort that Amanda took to get into the science of I-O, but regarding the intersection or the complementary of art and science. I looked into this and my wife helped me out with some background reading. I was drawn to a quote from the artist Francoise Gilot, who spent 10 years living with Pablo Picasso and then married Jonas Salk, who created the polio vaccine. She was asked, "What is it like? You two are completely different." What she said was, even though we are in different fields, we had the same intrinsic drive. The drive to get into an equation with the unknown, to pull something known out of something unknown. And that just struck a chord with me. Because I think of the scientist waiting to see that new image coming back from a spacecraft. Which, as Mark said and as Linda said, it changes the paradigm. It changes the book, because hypotheses are disproved and new hypotheses form. I think of the composer with her hands poised above a keyboard, waiting to strike that first chord. I think it's the same mindset. I think it's the same thing.

Mat Kaplan: Well done, Ashley. Mark Sephton.

Mark Sephton: I agree. That's it. I was lucky enough to see the orchestra yesterday. How the limits of what's possible musically was stretched, the attention to detail. It was like a research project. I think art is science and science is art. Anybody who's a scientific researcher like me, knows that you have to look at things with fresh eyes sometimes. You have to go and seek inspiration, come back and find new ways forward. That requires a creative mind. So I think we've got more in common than is different. I think if people could recognize the similar approaches that science and art require, they'd see, it's just one long continuum of activity.

Mat Kaplan: Linda?

Linda Spilker: Well, in fact, I was going to add that the Moon Symphony, the project itself is kind of like a space mission. You have to pay attention to that detail, and work so hard to finally have it come to fruition, hearing the orchestra play that music.

Mat Kaplan: I'm afraid we're going to have to stop at this point. I do want to give Amanda the last word. What's next? When are we going to be able to hear what was recorded yesterday and what is still being recorded at Abby Road?

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: So we have a trajectory which is a digital release in October this year. We've got a small timeframe to get all the elements and the record sorted, ready for that release. I think we're going to be able to do it. And once that is available for digital download, we are already knitting together a plan for a world premier. We're just trying to identify where on planet earth that's going to take place. I think part of the vision has always been the glorious Royal Albert Hall, partly because it looks like a moon. We don't know. We're just open and fluid and flexible about how that will manifest. But right now I think I'm just really enjoying this phase of it, which is the recording. Having the scientist with me is more than dreamy. And of course, The London Symphony Orchestra, the best orchestra on the planet. I suppose I'm concerned what a luxury it is just to have us together after everything that we've been through in the last two years.

Amanda Lee Falkenberg: I think more than ever, this symphony is basically the theme of planet earth the last two years, that we are together, united and whole. So thank you for that.

Mat Kaplan: What a wonderful place to end. Thank you, Amanda Lee Falkenberg. Thank you, Linda Spilker and Ashley Davies of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, not far from our headquarters at The Planetary Society in Pasadena. And Mark Sephton of Imperial College London, thank you to you as well for joining us. And to Tom Spilker, who jumped in there at the end. Thank you, Tom. Many thanks also to Imperial College London, which has made this possible, this gathering. And again, thank you to all of you who came out here on a rainy night in London. Ad astra, which means to the stars, and to the moons as well. Thank you everyone and good night. Planetary Radio live on the evening of Monday, May 23rd. Time for What's Up? on Planetary Radio. We are back with a brand new What's Up? Bruce is virtually sitting across from me here in this online session. It's good to see you again after a couple of weeks.

Bruce Betts: Good to see you. Welcome back from your trip of fun and work and goodness.

Mat Kaplan: Work and pleasure, and even the work was a pleasure. So it was quite a couple of weeks.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, you're a wild man. As I told you before we went on the air, just hearing about your trip makes me tired.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. I don't blame you. I'm still definitely jet-lagged. So wake me up. Tell me about that beautiful sky.

Bruce Betts: Pre-dawn is just going to be the focus. The planet party, it just continues. They're wild and crazy. Jupiter and Mars did their close-up thing. They are still close and they're moving apart. So check out the pre-dawn east, lowest down is super bright Venus. Well, you might pick up Mercury, even farther to the lower left of Venus, but it'll get higher. Just wait. So mostly start with Venus in the lower left. Then move up to the right and you'll see reddish Mars, and then very close to it bright Jupiter and farther up to the right is Saturn. They're all just going to spread out across the sky over the coming weeks and months. It's good stuff. We move on to this week in space history, 1965, first American space walk by Ed White. And 1968, three years later ... unrelated, except for heading into the moon, Surveyor 1, the first US lunar soft lander, landed.

Mat Kaplan: And what a triumph that was when Surveyor 1 made it. The very first attempt by a surveyor to make a soft landing up there. Especially after Ranger took ... oh, I don't know, several tries before they got it right.

Bruce Betts: But it made some nice small craters. Of course, Ranger was a high-speed impact design to do that anyway. It just was supposed to function before then. Eventually they got one working and the Surveyor program was very successful, as was the Lunar Orbiter. Random space fact, a random, random space fact. I'm just not done with that yet. So on Apollo 11, there was a small disc, kind of the size of a big coin, that Buzz Aldrin carried and was dropped onto the moon, that contained goodwill messages. Statements by presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, and messages of goodwill from leaders of a whole bunch of countries around the world. It also had leadership of Congress, NASA top management, all sorts of names that were shrunk down and put on there and still hanging out on the moon. Somehow I'd missed that until now. So there you go. We'll come back to that in a little bit.

Mat Kaplan: I didn't know that either. Yeah, glad we're coming back to it too.

Bruce Betts: We have a lot of trivia questions to get to.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. The first of these is your answer to the question that we asked way back on May 11. We had to do this I went out of town and last week was pre-taped, but we're ready now. What was that question?

Bruce Betts: I like this one. We asked you, why is there a depiction of a snake on the Perseverance Rover? How did we do, man?

Mat Kaplan: Big response to this one. I'll let the poet laureate of Planetary Radio, Dave Fairchild of Kansas, provide what he believes was the answer. Rod of Asclepius etched on aluminum, traveled to Mars as an honor to those putting their personal health on the line in the fight against COVID when it first arose. There on the lander, the rod and the snake are supporting the earth. It's a virtual sign, thanking the teams of our medical heroes who help us while putting themselves on the line. I had no idea. This was also adorned Perseverance.

Bruce Betts: I didn't realize it either and it's worthy of notes. Obviously those people deserve our thanks and gratitude, so it's kind of neat.

Mat Kaplan: Christopher Mills said, this was nice for me to learn about, since I'm a practicing ER doctor in Northern Virginia fighting the pandemic for two years now. Much appreciated, Perseverance. And then we also got a similar note from Kevin Nitka in New Jersey, also working in healthcare. Thank you to all of you out there who have been on the front lines in dealing with this terrible disease.

Bruce Betts: Yes, thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Devon O'Rourke in Colorado, sending a snake to Mars, very much against planetary protection protocols.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. I didn't look into how they resolved that, but it's a two-dimensional snake functionally so I think that may be the exception.

Mat Kaplan: Marcel-Jan Krijgsman in the Netherlands. He was actually kind of hoping it was the logo of the Python programming language, since it does run on ingenuity. But healthcare is good too, he says.

Bruce Betts: No comment.

Mat Kaplan: Christopher Lowe, a bonus meaning of the snake is so that the Martians don't actually step on the Rover. Apparently it sounds like a version of Don't Tread on Me. Gene Lewin in Washington sent a poem, but I'm also impressed by the image he sent. It was a bumper sticker that Perseverance does not have on board. It says, how's my driving? And then it provides a 202 area code number. I checked it. It happens to be one of NASA headquarters' main numbers.

Bruce Betts: And you saw that on the Rover? No.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, just only in Gene's imagination and in the image that he faked. Finally, we did get this little quick ditty from Gregory Vandersluis in Quebec, Canada. A pandemic may have slowed our pace but the perseverance of the human race, is forever festooned on a Rover in space.

Bruce Betts: Oh, another nice poem.

Mat Kaplan: After all that, I should probably tell everyone who won.

Bruce Betts: Why start now?