Planetary Radio • Oct 27, 2021

Sally Ride: Revisiting our 2005 conversation

On This Episode

Sally Ride

First American Woman in Space

Rae Paoletta

Director of Content & Engagement for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Host Mat Kaplan has wanted to reshare his first conversation with the great Sally Ride for years. Sally talks about women in space, the loss of space shuttle Challenger, and her devotion to sharing the wonders of science with young girls through Sally Ride Science. Planetary Society editor Rae Paoletta takes us to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. Is it shrinking? We also celebrate the return of the space trivia contest.

Related Links

- A conversation with Sally Ride

- Sally Ride Science

- Research vessel Sally Ride

- The shape of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is changing. Here’s why.

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

Who was the first person to fly a second orbital mission in space?

This Week’s Prize:

Another safe and sane Planetary Society Kick Asteroid r-r-r-r-rubber asteroid.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, November 3 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Winner:

We’ll announce the two most recent contest winners in our Nov. 3, 2021 episode.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: My first conversation with the great Sally Ride, this week on planetary radio. Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of the Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. I'm back from vacation, but not in time to produce an entirely new episode of our show. Oh, we've got a new "What's Up" visit with Bruce Betts, and you're about to hear my colleague, Planetary Society editor, Rae Paoletta give us the latest on that Queen of Storms, Jupiter's Great Red Spot. Headlines from The Down Lake, our weekly newsletter, will also have to wait till next week, but it's always a good read at planetary.org/downlink.

Mat Kaplan: The main feature in this week's show is something I've wanted to share again for many years, Sally has always been very special to me and not just because she was the first American woman in space. It's much more who she was, and what she did with her life after her two missions on space shuttle Challenger, and that's most of what you'll hear her talk about right after we visit with Rae. Rae, welcome back to Planetary Radio. Are we losing the, well as someone in your article calls it, the GRS?

Rae Paoletta: Well, Mat, thanks, first of all, for having me back. Secondly, we're just not sure yet. I think we'll have to wait and see.

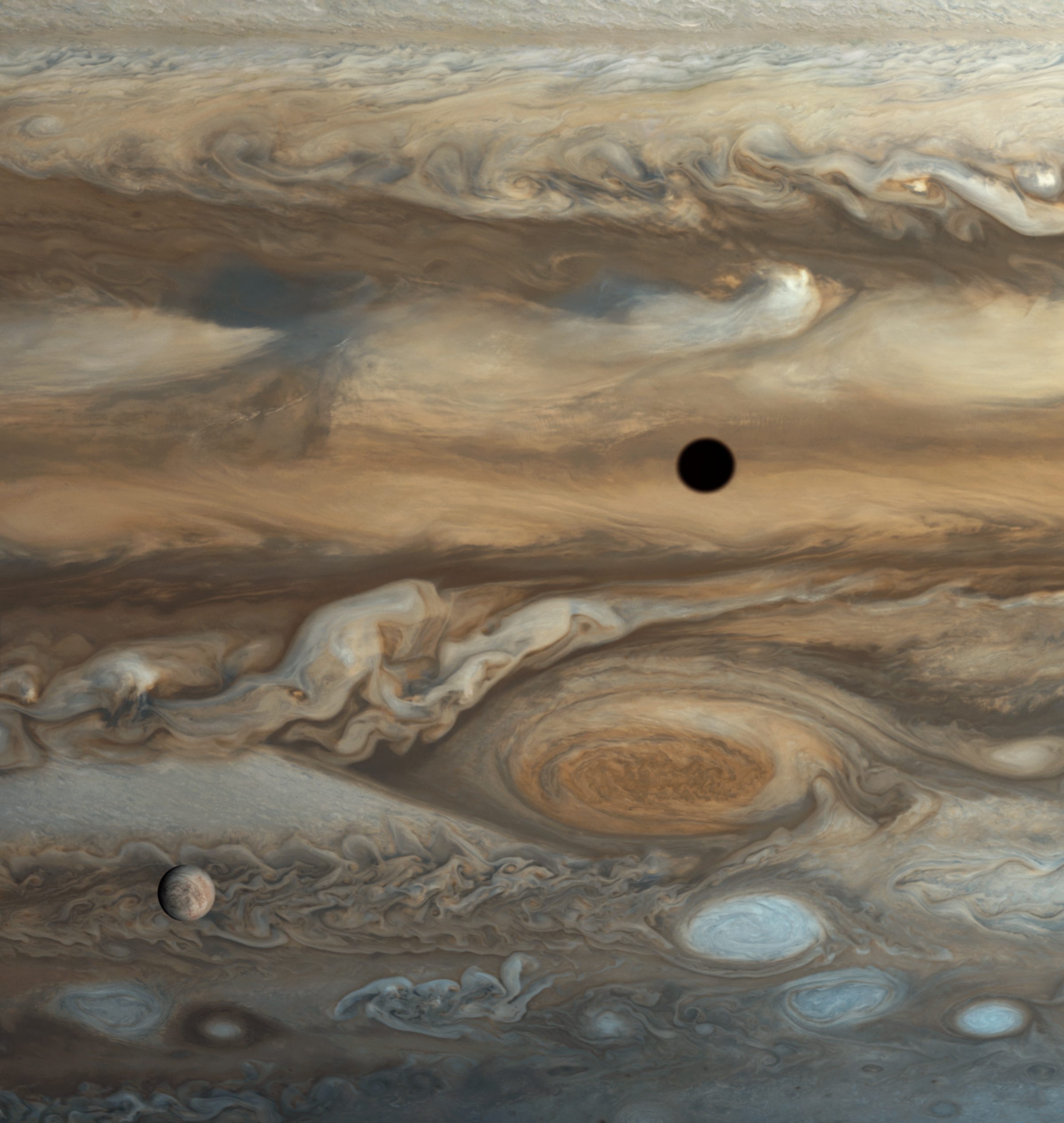

Mat Kaplan: That is so interesting. We have these close up looks, going back to Voyager and I should say, you have two of the most gorgeous images ever of the Great Red Spot in this piece, which is an October seven piece that you can find a planetary.org. It's titled "The Shape of Jupiter's Red Spot is changing, Here's Why", and it's by Rae of course. Have we seen it shrink in the time that we've been observing it?

Rae Paoletta: It's an interesting question with a sort of ambiguous answer, right? It does appear that perhaps the Great Red Spot, as we know it, is shrinking. At one time during the Voyager era, for example, it seems it was about three times the size of Earth, or could fit three earths inside of it. Now it's a little over one Earth. So yes, there does appear to be evidence that it's changing shape, shrinking perhaps, but the way in which it changes and whether or not that's linear and whether or not it's disintegrating is really the bigger question.

Mat Kaplan: Just one Earth. Why that's minuscule.

Rae Paoletta: A blip on the radar, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Oh man. Is it also possible that this is a cyclical thing?

Rae Paoletta: You know, what's interesting. There have appeared to be over the last however many years, some evidence of, of course, the spot changing in some regard, right? A few years ago in 2019, amateur astronomers found that the Great Red Spot was flaking. Pieces of it appeared to be breaking off the main body of the storm. And no one at the time really knew what it was while we don't think that's necessarily a 1:1 piece of evidence that says, "Hey, the spot is shrinking." There does seem to be evidence over long periods of time that perhaps it's changing shape and that not only is it maybe getting smaller in general, it's becoming less cigar like, and more circular.

Mat Kaplan: You mentioned in the piece that we've been observing the Great Red Spot for at least 150 years. Do we have any idea how old it actually is?

Rae Paoletta: That's another one of the mysterious questions that only the Spot really knows. It doesn't appear that we have a great decisive period of time where historians can look back and say, "you know what? This is when the Spot appeared," because there were some cases from, I believe it was the 17th century, where we have some writing from folks who think they saw a spot on Jupiter, but scientists now don't believe that that actually was the Great Red Spot. It is a subject of debate, but for now, just to be conservative, I like to say we've been tracking it for about 150 years and it's possible that the Spot of course existed before that.

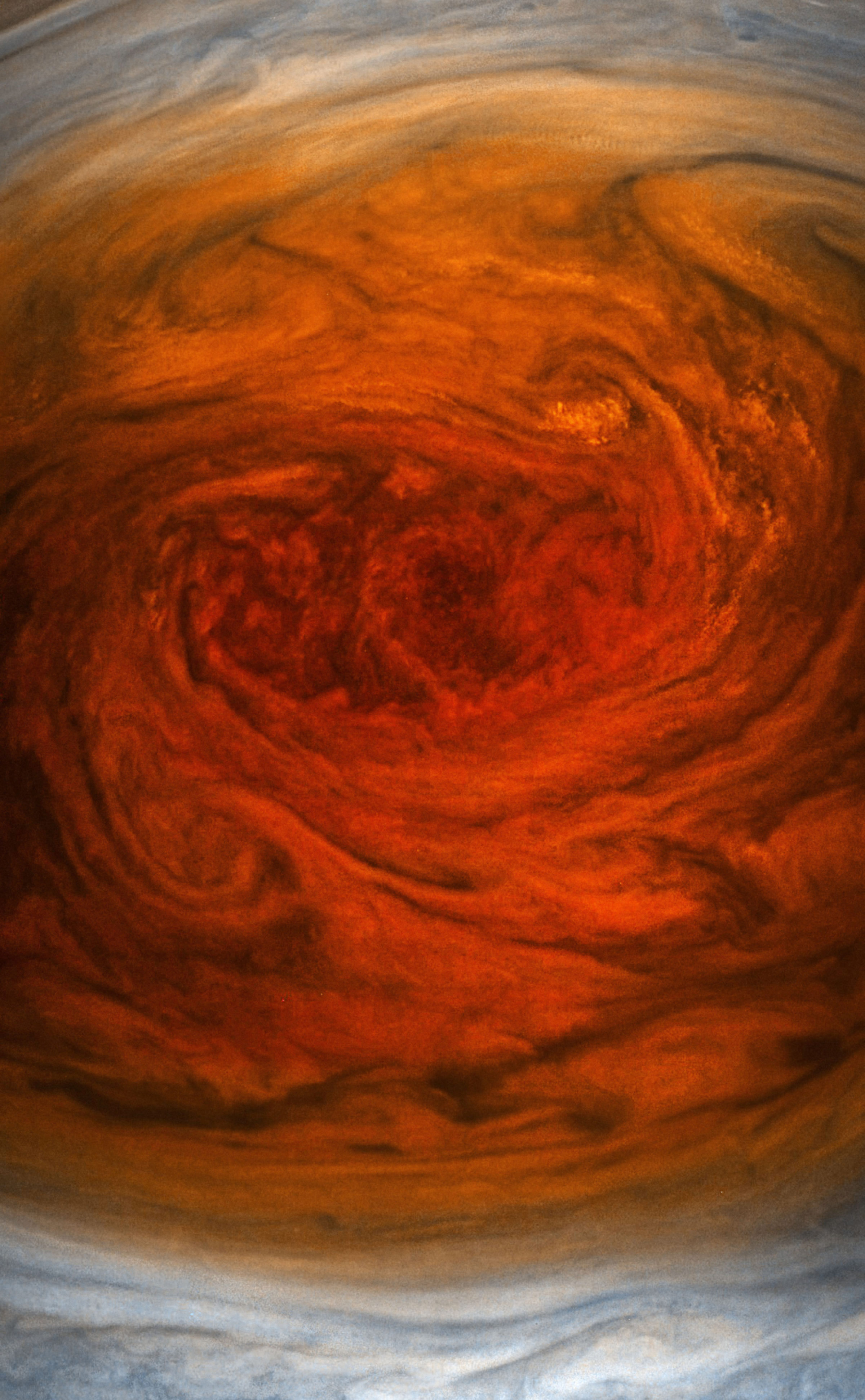

Mat Kaplan: Let's move on to that gorgeous red, not to say redhead, although I suppose it may only be, according to your article, if the color is on top, are we any closer to understanding what makes it so?

Rae Paoletta: Not quite Mat, I wish that we had some better answers for this because it does seem to be at the crux of the Great Red Spots, a great red conundrum, right? We've got this beautiful storm on this incredibly swirly and chaotic planet. And we have some ideas on why the Great Red Spot is red. But to be honest, we just don't know why. It seems that there are two schools of thought and there's a little bit of science drama here, which of course we all know and love. And it's see is that some scientists think the red color comes from maybe some sort of chemicals that come from somewhere beneath the storm's cloud tops. But then on the other hand, other researchers say that the rusty color may be coming from sun that's splitting up various chemicals in the storm's upper atmosphere. So relatively shallow area where we're seeing the "sunburn" at the top. It's a possibility that the rest of the storm is really not very red at all.

Mat Kaplan: I'm torn while I would, like you and so many scientists and others out there, would love to understand what's going on here. I'm also intrigued and charmed by the mystery of this storm that we have been watching, as you've said, for at least that 150 years. I didn't mention that the other one of the beautiful images, it really is amazing. And it's from Juno, not surprisingly, the spacecraft that is still orbiting Jupiter right now, or you want to describe it?

Rae Paoletta: Yeah, absolutely. This is one of the most incredible space fixtures I think I've ever seen in my life. It's basically an image that Juno captured during its seventh close fly by, which was on July 11th, 2017. And in this fly by Juno was really, really close up to the Great Red Spot. And I mean, you can tell. You can see these swirling bands of red and crimson detail that kind of floats into this orange color. I mean, it really looks like an impressionistic painting or something. It's just so hypnotizing, I would say mesmerizing perhaps words kind of fail to describe it.

Mat Kaplan: Indeed they do. And I hope it's with us for a long time to come. Rae, thank you so much for this great piece. And for joining us again.

Rae Paoletta: Always a pleasure, Mat, thank you.

Mat Kaplan: That's Rae Paoletta editor for the Planetary Society and the author of this October 7 piece about everybody's favorite storm in the solar system, the Great Red Spot.

Mat Kaplan: There's a ship that births in San Diego bay that I'm always happy to see. It's a big research vessel called the Sally Ride. It belongs to the US Navy, but it is operated by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scientists and students from throughout the United States sail the world aboard it in investigating climate change, new technologies, human health, and much more. It's a fitting tribute to Sally who spent nearly two decades as a professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego.

Mat Kaplan: What you're about to hear is exactly as it was broadcast on April 17th, 2005, long before Planetary Radio became a podcast. The only correction I need to make is the web address for Sally Ride Science. It is still going strong, but you'll now find it at sallyridesciencedotucsd.edu. I highly recommend checking it out, especially if you have curious kids around. I've also decided to leave in place the public service announcement that was originally part of that show. It features another space traveler you may have heard of, here, beginning with our old theme music, is Sally.

Mat Kaplan: First of all, Sally Ride, thanks very much for inviting us into your San Diego headquarters, which as busy as we can hear with the telephone ringing.

Sally Ride: Oh, it's my pleasure.

Mat Kaplan: Almost 22 years, since your first flight on Challenger, you attracted an enormous amount of attention. Now, when a space shuttle flies, eyebrows would only be raised if there weren't one or two or more women as part of the crew. In fact, in the return to flight scheduled for spatial discovery, when this is heard only maybe a month after this program is being heard by our audience, the commander is a woman. What kind of a change does that indicate? Is that a positive bit of evolution on our part?

Sally Ride: Oh, it's wonderful, isn't it? I think it's something that was a little while in coming in the astronaut core and the astronaut program. When I came into the astronaut core, there were six women brought in at the same time. Six of us came in together. I had the fortune of being the one that was chosen to fly first. All six of the women went on to fly in space and as future astronaut classes were brought in, more and more women were brought in. Until today, the astronaut core is between 20 and 25% female. And as you said, it is now very rare that the space shuttle goes up without at least one woman on board. And it's now common that there'll be two women, occasionally three women, on board a flight and with Eileen Collins now commanding her second space shuttle flight, with the upcoming return to flight. You know, it really just shows how important women have become within not just the astronaut core, but the space program in general.

Mat Kaplan: That's exactly where I wanted to go next because we've followed that a bit on this program in the aerospace industry, in NASA and that there has been progress. I mean, we can go to JPL now and have a great time talking to Linda Spilker, as we did two weeks ago, the deputy project scientist for Cassini, but I guess there's still some room. And that seems to be much of what your life is dedicated to.

Sally Ride: There's still a lot of room and I'll echo what you just said, all you need to do is walk into mission control at Johnson Space Center in Houston, during a simulation or during a shuttle flight. And it looks very, very different than it did back in the Apollo days. There was all male. Now there are many women who are involved in mission control, actively controlling the shuttle, but there's still a long ways to go. And the statistics are that only 11% of engineers in the country today are women. Only 20% of scientists in the country today are women. Now, those numbers are way up from the 1970s when, believe it or not, less than 1% of the engineers in this country were or female.

Mat Kaplan: As recently as that.

Sally Ride: As recently as that, so it's been an enormous change in just a few decades, but there's still a long ways to go. And what I'm seeing in my work now is that there are lots and lots and lots and lots of girls out there who are really interested in the space program. They're interested in science, they're interested in engineering, but they still don't have quite the encouragement and support that boys their age do.

Sally Ride: They don't have quite the programs available to them. And a funny thing happens to girls in particular, as they go into middle school, grades five through eight, suddenly, hormones start to kick in a little bit. It's important to be accepted. It's important to be liked. It's important to do what you think, your friends, maybe your teachers, your parents are expecting you to do. May not be cool to be the best one in the math class. The girl says she wants to be an aerospace engineer at age 11, she might get a slightly different reaction than a boy who says exactly the same thing. So the result is that we start to lose both boys and girls, but far more girls than boys from the technical field, starting at about middle school.

Mat Kaplan: The often quoted, almost cliche, but no less true is the comparison between girls' interest in science and math in the fourth grade compared to the eighth grade. Where fourth grade, it's what essentially equal to the boys.

Sally Ride: Exactly right. It is equal to the boys, in fourth grade 68% of boys will tell you they like science and 66% of girls will tell you they like science. It's the same. And then in eighth grade, what you find is eighth grade, early high school there are five times as many boys who are thinking about engineering as a major in college, than girls. So there's a huge change that happens over those middle school years. And what I'm trying to do with Sally Ride Science is support those girls, give them programs to participate in, offer role models and mentors who are female, put female faces on all these careers. Show them there are lots of other girls just like them who have these interests and try to publish materials that are gender neutral, that the girls will like, as well as the boys.

Mat Kaplan: I want to talk about all these different things that Sally Ride Science and Sally Ride are into, maybe after our break in a couple of minutes. But to talk a little bit more about the context for all this, the challenge bringing girls and young women into science and engineering may be even greater than it is for men. But we've talked on this show about the critical importance of the need for more scientists and engineers period in this country, if we're to proceed and retain the leadership. If indeed we still have it in so many areas.

Sally Ride: Oh, it's absolutely right. The science and technology are the engines that drive our economy. Our society depends on the intelligence, the creative minds, developing the technologies of the future. And what we're finding right now is that we've got a real shortage of American born scientists and engineers in this country. We've been importing scientists and engineers for quite some time now. We really need to do something at the early stages of the education process to not only make sure that kids have the background to go into science and engineering, but maybe more important, that they've got the interest and the energy and the enthusiasm for it because they're not choosing to go into science and engineering in the numbers that our society really needs and wants.

Mat Kaplan: Our guest is Sally Ride the first American woman in space on The Challenger space shuttle, two trips on Challenger. We'll come back to that, but we will also, after we take this quick break, talk more about what she is doing with Sally Ride Science and particularly directed toward American girls and young women. And we will do that right after this break.

Buzz Aldrin: This is Buzz Aldrin. When I walked on the moon, I knew it was just the beginning of humankind's great adventure in the solar system. That's why I'm a member of the Planetary Society. The world's largest space interest group. The Planetary Society is helping to explore Mars. We're tracking near Earth asteroids and comets. We sponsor the search for life on other worlds, and we're building the first ever solar sail. You can learn about these adventures and exciting new discoveries from space exploration in the Planetary Report.

Commercial Voiceover: The Planetary Report is the society's full color magazine. It's just one of many member benefits. You can learn more by calling 1-877-planets, that's toll free 1-877-7526387. And you can catch up on space exploration news and developments at our exciting and informative website, planetarysociety.org. The Planetary Society, exploring new worlds.

Mat Kaplan: Every once in a while, we're lucky enough to get somebody who, well the cliche is, needs no introduction. And we have one today. Sally Ride, first American woman in space, now on the faculty at UC San Diego. Near and dear to my own heart, because I have an older daughter there, going to be there for a little while longer. We are not too far from there, in San Diego at the headquarters of Sally Ride Science. Let's do what we said we would before the break and talk a little bit about what happens out of this suite of offices, because you have a lot of different facets to Sally Ride Science.

Sally Ride: We do. We put on events, we organize programs and we publish materials all aimed at encouraging girls, primarily in upper elementary school and middle school, in science and math and engineering.

Mat Kaplan: So just when they're beginning to feel the pressure.

Sally Ride: Exactly. We want to focus on that age group because we know in elementary school, they've got the enthusiasm. We don't need to convert any of these girls to science. We just need to capture that enthusiasm and give them support through the middle school years. As an example, we run one day science festivals for middle school girls at colleges around the country. We've done them at Stanford, at University of Michigan, at MIT, University of Central Florida, University of Missouri, Kansas City, Cal Tech. We're going to be doing our next one in Pittsburgh on May 7th at University of Pittsburgh. So anyone in the Pennsylvania area who'd like to come and see me and bring their daughters and have them ask questions is more than welcome.

Mat Kaplan: Listen up Allentown listeners.

Sally Ride: But our focus at these is to have a real entertaining day around science. So we have a street fair with booths and exhibits for the girls. They can make slime, they can drive robots, they can look through telescopes. I give a keynote talking about what it's like to be an astronaut and answer lots of questions from the girls. And then, probably most important, we have a whole series of workshops given by female faculty members or female scientists and engineers from the community who talk about what they do and why they enjoy it. And it really does put a female face on those careers for the girls.

Mat Kaplan: What about the camps that you've run on some of those same campuses? Although I know Berkeley also has been a location.

Sally Ride: Absolutely, the festivals we love they're great one day events, but they're only one day. We want to try to give the girls more support, so we've started summer science camps for girls, sleepover camps. We've had very good luck with the Stanford camps over the past two years since we started they've been sold out both summers. So this summer we're actually expanding to UC Berkeley and to University of San Diego, and we have started taking applications for the summer camp. So again, any girls in grades five through eight, who will be entering six through nine over the summer are welcome to attend.

Mat Kaplan: Mention the website now, and we'll do it again at the end of our conversation. And of course we'll post it on the Planetary Society website, planetary.org, right where this show can be heard. But what is that URL?

Sally Ride: The best website to find out about all of our programs is www.sallyridescience.com. And that can get you to information about out the festivals, to the camps, to our national toy design competition, toy challenge, and also give information about some of the books and career books that we publish for girls and other books that are related to space and to other areas of science.

Mat Kaplan: I was on the website, exploring all the stuff about the toy design competition.

Sally Ride: Great.

Mat Kaplan: Which is fascinating. So I'm glad you brought it up. Talk about that.

Sally Ride: That is for both boys and girls. And the idea here is that no matter what you're going to design, whether you're designing a rocket engine or a toy, you go through the same engineering design process. So this is an effort to get again, middle school kids, boys, and girls involved in engineering, without them really even knowing they're involved in it. We picked a design project, toy design, that we think will appeal to all kids. Hasbro is the founding sponsor, so how cool is that? And we've got Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society, is one of our other principal sponsors. We're holding this year's nationals in San Diego, on the west coast and in Raleigh, North Carolina on the east coast coming up towards the end of April and beginning of May. And we've had thousands of kids from all over the country form teams to design toys. They come up with their own creations and they're brilliant toys.

Mat Kaplan: And one of the categories, I think, was to design educational toys for younger children.

Sally Ride: Absolutely. We've got a whole series of, of toy categories, including one that is educational toys for your younger brother or sister.

Mat Kaplan: You have also authored and coauthored several books. I guess those are also available from Sally Ride Science. Although I saw some of them on Amazon at least.

Sally Ride: Yeah. Actually most are available on Amazon. We've just republished in second edition, two of the books that are only available through Sally Ride Science, but all are related to space. Third Planet: Exploring Earth From Space, a book on Voyager and its missions to the outer planets exploring our solar system. So my roots are in space. So that's what the books have been focused on.

Mat Kaplan: To space and Back 1986, was that the first book that you wrote?

Sally Ride: That was the first book that I wrote. It was while I was still in the astronaut core. I Actually wrote it while I was in training for my third flight, which never happened as a result of the Challenger accident.

Mat Kaplan: And you say actually in the introduction to the book that you were about to come out with a book. I guess you just finished writing, when the Challenger accident took place. You had been a crew member on Challenger twice. Did you feel some kinship to this other crew, this lost crew, which in fact, you ended up dedicating the book to.

Sally Ride: Oh absolutely. Of those seven crew members, four were actually from my astronaut class, the astronaut class of '78. So we all came in together, we trained together, we had dinner at each other's houses, we partied together on the weekend. So I knew them very, very well. And it was my spacecraft, it was the shuttle that I had been on. So I was very, very close to the crew, and to the accident

Mat Kaplan: Was Judy Resnik, one of those who you had been through astronaut class with?

Sally Ride: Yes. Judy was in my astronaut class and she and I were very good friends. We both spent a lot of time working on and developing the space shuttles' robot arm. So we spent a lot of time together just on that, knew her family, knew her very well.

Mat Kaplan: You get asked the same questions all the time. Of course, I've asked several I'm sure today that you've heard a few hundred times and one of them, that you've acknowledged is you get asked, isn't it dangerous? And if it's dangerous, why should we be going up there? That's a good way to turn things around before we say goodbye.

Sally Ride: It's probably right. You know, it is dangerous. It is risky. Astronauts understand those risks very well. Every astronaut has to internalize those risks for him or herself. But I think that the value of space exploration is that it really speaks to our inner soul. I mean, we are explorers. We're a species of explorers. It's what we do.

Mat Kaplan: It's what we do.

Sally Ride: And it's what we've done since people first stood on two legs and started walking around and space exploration is today's embodiment of that. And you can see it when you go talk to any group of kids, they're fascinated by space exploration. They're fascinated by astronauts. It's something they would love to do when they grow up it is absolutely worth the risk because it's a real important part of who we are.

Mat Kaplan: And of course, we ask those questions from a certain bias that might be expected from the Planetary Radio.

Sally Ride: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: Any message for that discovery crew, that's going to make the return to flight about a month after this is heard.

Sally Ride: Oh, well I wish them all the success in the world. I know that they're deep in training. They're ready to go and eager to strap in and start the countdown.

Mat Kaplan: Sally Ride Science, was it .com?

Sally Ride: Sallyridescience.com.

Mat Kaplan: And we will put that on the website as well. And by the way, while people are there, lots and lots of corporate support for what you're up to here, which I would hope they would think of as enlightened self-interest.

Sally Ride: Well, that's exactly right. We have a lot of corporate sponsors and the corporate sponsors that we have are sponsors because they know that it's important to reach kids in upper elementary and middle school. Because if you don't reach them, then you're not going to get them back.

Mat Kaplan: And they need them, they're going to need them in a few years as their employees.

Sally Ride: They need them and they need the girls, as well as the boys.

Mat Kaplan: And well educated voters as well, even if they don't end up in science.

Sally Ride: That's exactly right. I think that that's a point that I always try to make is that we're not necessarily trying to make all of these girls and boys scientists. It's so important to be scientifically literate these days, that just to be an informed citizen, they should have a good background knowledge and middle school, high schools when they get it.

Mat Kaplan: Sally Ride, thank you so much for taking a few minutes here at your headquarters for Sally Ride Science in the San Diego area. We wish you continued success.

Sally Ride: Thank you very much.

Mat Kaplan: And we will be right back with Bruce Betts and this week's "What's Up," including the space trivia contest. After this return visit from Emily.

Mat Kaplan: Sorry everyone, no Emily, but I hope you enjoyed my first conversation with Sally ride. It can still be heard in our April 17th, 2005 episode, that includes Emily. We've got the link on this week's page at planetary.org/radio. We lost Sally in 2012, but her legacy is very much alive in Sally Ride Science, which is celebrating its 20th year under Sally's longtime companion, co-founder, and executive director Tam O'Shaugnessy. And I just learned that Sally will be one of the women honored next year, when the United States mint puts her on a 25 cent coin, it is time for "What's Up" on Planetary Radio. I am back from vacation, barely, and here to welcome the chief scientist of the Planetary Society, that's Bruce Betts, who a little bit later, will be returning us to the space trivia contest as well. Welcome.

Bruce Betts: Hey, yay! More contest. But first, night sky. Look over to the east and you'll see super bright Jupiter with Saturn over hanging out near it to its right. And in the pre-dawn sky, you can still catch Mercury. If you have a view very low to the Eastern horizon and the pre-dawn, it will actually be hanging out next to the moon on the 3rd of November and, bonus, the bluish star, Spica. Let us move on to this in space history, shall we? 1991, which I think was 30 years ago, the first ever close asteroid fly by was Galileo flying by Gaspra, 30 years ago this week.

Mat Kaplan: I did not remember that. Thank you. Go ahead.

Bruce Betts: And in 1934, Carl Sagan, one of the founders of the Planetary Society was born.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, Happy Sagan day.

Bruce Betts: Alright. We move on to Space Fact!

Mat Kaplan: That's a blast from the past. I've heard that one before.

Bruce Betts: Oh, I'm sorry. The north star, you may have heard of it, Polaris. It's actually about two thirds of a degree away from the pole of rotation. So about one and a half times the moon diameter. So it actually revolves around the pole in a small circle about one in 1.3 degrees in diameter. And it'll be closest to the pole as the pole weaves and wanders in about the year 2100. So look for it there.

Mat Kaplan: That's good. I'm going to save my next big camping trip until then. So I can find my way.

Bruce Betts: Hopefully you're not taking another vacation until then.

Mat Kaplan: I probably won't, the way things go.

Bruce Betts: I mean, geez.

Mat Kaplan: We do not have answers for a trivia question, but we will have two trivia questions. Trivia contest to resolve next week. So stay tuned for that. But Bruce does have, I think, you have a brand new contest for us.

Bruce Betts: I do indeed. Here's your question? Who is the first person to fly a second orbital mission in space? Second orbital mission in space. The first person to do that, go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: So it has to be somebody who did two orbital missions, and did those before anybody else. Can't be a suborbital and an orbital?

Bruce Betts: Correct-o-mundo!

Mat Kaplan: There you have it. You have until the 3rd of November. Wow. The 3rd of November. That's a Wednesday at 8:00 AM. Pacific time to get us this answer. And one more time, we will have awaiting you a Planetary Society. Kick asteroid, rubber asteroid. I think we're done.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there, look up the night sky and think about weasels. Thank you. And good night.

Mat Kaplan: Weasels? We got any Frank Zappa fans out there? Weasels? Really? Yeah. Okay. Hey, I didn't know you were a Zappa fan. That's Bruce Betts. He's the chief scientist of the Planetary Society and he joins me every week here for "What's Up." Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by it's members who cherish the legacy of space exploration. Go to planetary.org/join to learn more. Mark Hilverda and Jason Davis are our associate producers. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth