Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 18, 2011

Congratulations to the Dawn team on their orbit entry & pretty pictures!

There's a new orbital mission on the map! As of Friday, the relatively small mass of the asteroid Vesta (it only weighs in at a bit under 300,000,000,000,000,000,000 kilograms, or half a ten thousandth of Earth's mass) has finally taken hold of its new artificial satellite, Dawn. But that's a tenuous grip, so for the next three weeks Dawn will continue applying its ion engines to tighten the orbit, spiraling inward from its orbit capture altitude of 16,000 kilometers until it has reached an altitude of 2,700 kilometers. Only then will Dawn officially be in Survey Orbit.

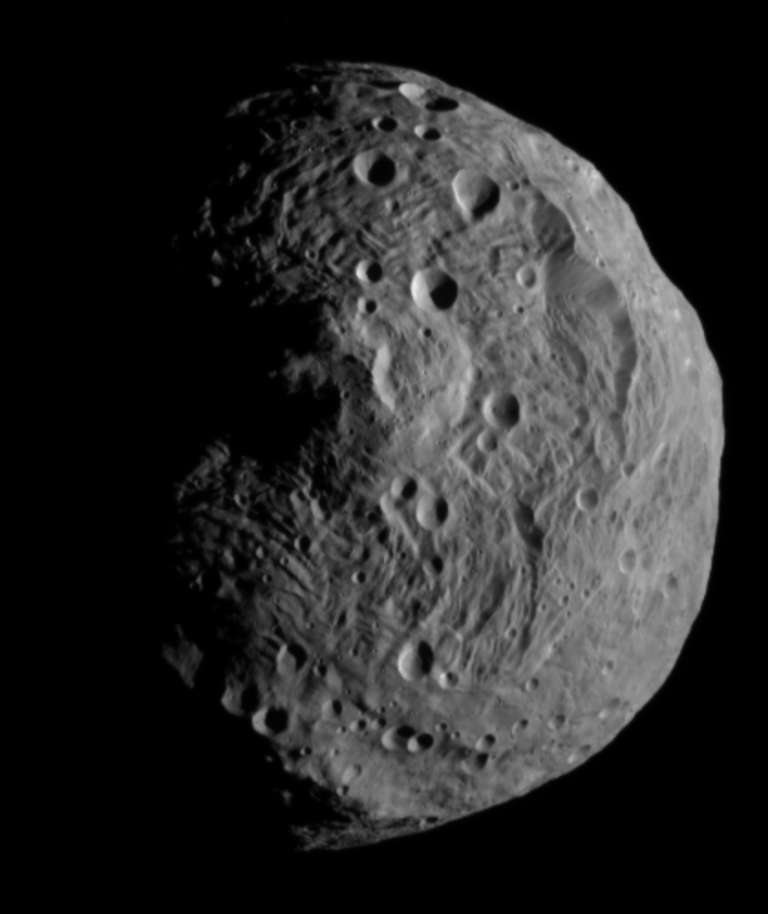

This announcement came on Friday but I was hoping they'd release a new image from the new altitude, and today they finally did. Here it is, and it's a very pretty one, though there are some peculiarities I'll mention below. With this latest image Vesta has become, to me, a place-- no longer an imagined object, but a real one.

We're looking straight at Vesta's "nose," what is assumed to be the central peak of a crater so large as to be basically the same diameter as Vesta itself. It's also an ancient crater, relative to the other surface features on Vesta; when this crash nearly destroyed Vesta, the crater itself would've erased any earlier geologic features that it sat on, and its ejecta would have rained down all over the rest of the mini-planet (including within the newly formed crater), pretty much resetting the geologic history of Vesta's surface. (For more on that event, read this blog entry from February, which has cool videos.)

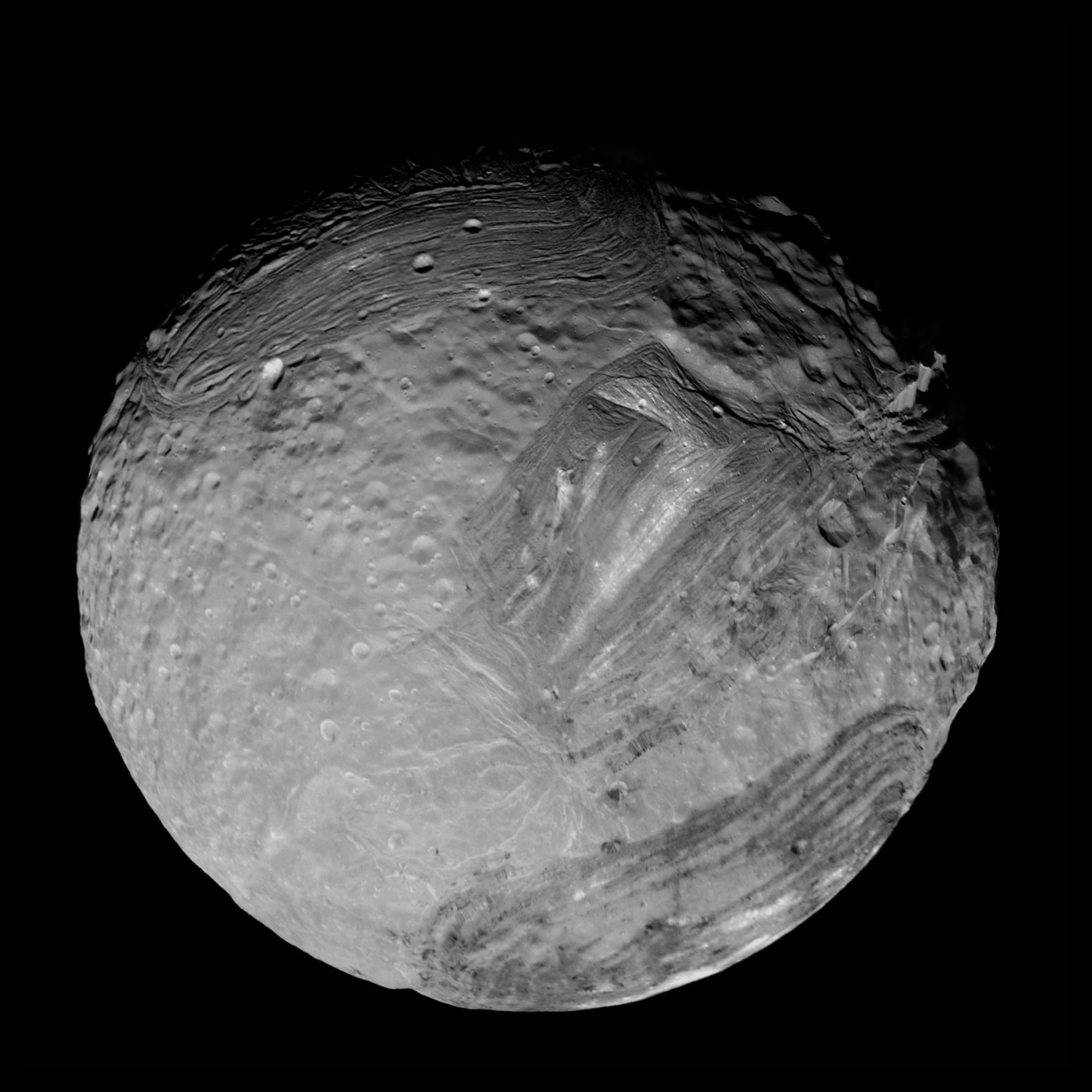

The interior of that south polar basin sure looks weird. All around the central peak are chevron-shaped ridgy features that bring to mind Miranda -- which, by the way, is very similar in size to Vesta. Such an unusual terrain, located preferentially within the interior of this gigantic crater, must have something to do with how the crater formed, at least that's the way I see it. I'm looking forward to seeing what this terrain looks like at higher resolution as Dawn spirals downward.

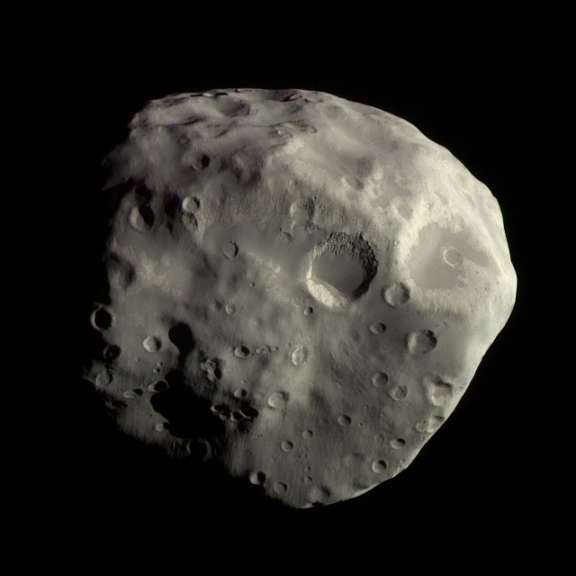

Whereas that "nose" reminds me of a much smaller, lumpier moon, Epimetheus:

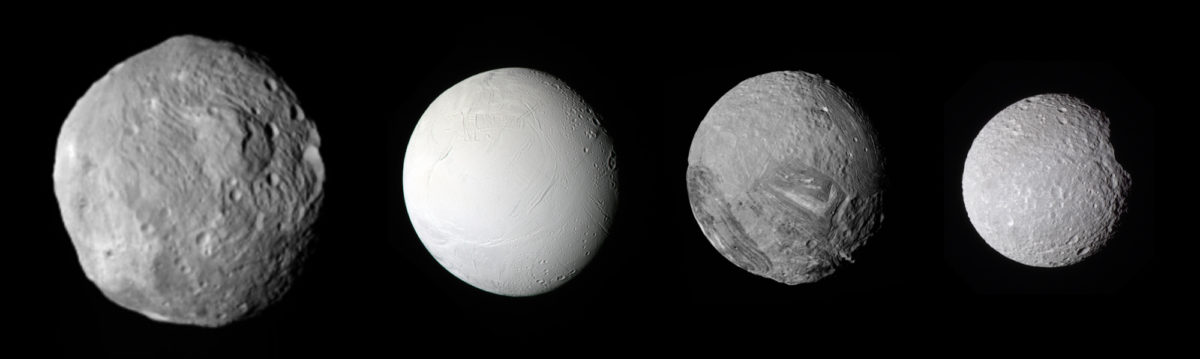

I find the smaller craters on Vesta to be strikingly bowl-shaped. Or maybe I find the bowl shapes of the craters so noticeable because there's so few of them. With relatively few craters, Vesta's surface is, as solar system surfaces go, young. Compare Vesta to another similarly sized body, Mimas, whose surface has many more craters, and you'll see what I mean.

Now that we're beginning to see Vesta's true character up close and personal, I'm itching to make these kinds of comparisons between our new views of Vesta and these other worlds we've already visited. But I've run into a snag: the image resolutions posted with the released images are wrong. Without knowing the correct pixel scales on the released images, it's tough for me to resize them for accurate comparisons to other objects.

Take this most recently-released image, for instance. The official caption states that "It was taken from a distance of about 9,500 miles (15,000 kilometers) away from the protoplanet Vesta. Each pixel in the image corresponds to roughly 0.88 miles (1.4 kilometers)." But that can't possibly be true: the released image shows Vesta 860 pixels across. Multiply that by 1.4 and you'd get a Vesta with a diameter of 1,200 kilometers -- way bigger than Ceres! What gives?

What happened is that they enlarged the images before they released them, but didn't correct their scale numbers accordingly. It's readily apparent that the images have been enlarged -- you can tell because they look blurry and there's a jagginess to the limb where their enlargement algorithm didn't do a very good job of smoothly interpolating the real shape.

The Dawn framing camera has an angular resolution of 94 microradians -- each square pixel projects to a 94-microradian square of sky -- so it makes sense that the image captured by the camera would initially have had a scale of 1.4 kilometers per pixel (15,000 times 0.000094). The original image would show Vesta, whose equatorial diameter is about 570 kilometers, at a bit over 400 pixels across. The image that they released has Vesta at 860 pixels across. So it's been enlarged by a non-integer factor, something a bit over 2. They should have divided the pixel scale by the same number, whatever it was; the released image shows Vesta at a scale of roughly 660 meters per pixel.

Sorry to belabor that point but it's been driving me kind of nuts, and although I've asked numerous people who have various official capacities on Dawn about the enlargement factors on the released images I haven't managed to get anybody to answer. But I'm tired of waiting, so I'm hereby posting an approximately scaled image of Vesta compared to some other interesting solar system bodies, assuming that the astronomer-derived equatorial diameter of 560 to 578 kilometers is correct. (The NASA websites keep referring to Vesta as being 530 kilometers across, but that's its average diameter; it's much fatter around the middle, 560 to 578, than it is pole-to-pole, 468. This wide range of possible diameters is why the true pixel scale of the images is so important -- there's a lot of room for error when I measure images and guess at what diameter Vesta should appear to be when seen from that orientation.) This picture is an update to this post from last year.

I will wait to get correct numbers for image scales from the Dawn mission before I post any update to my asteroid and comet montage.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth