Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 11, 2010

Rosetta's Lutetia pictures

I saw these pictures for the first time just 10 minutes before boarding my flight back home, and forced myself to download everything I could find as quickly as possible without pausing to actually look at them. (Well, except for the Saturn one, which I knew was coming. That one I had to post without even thinking about it.) Still, even in passing, I caught sight of lovely bowl-shaped craters and Phobos-esque grooves.

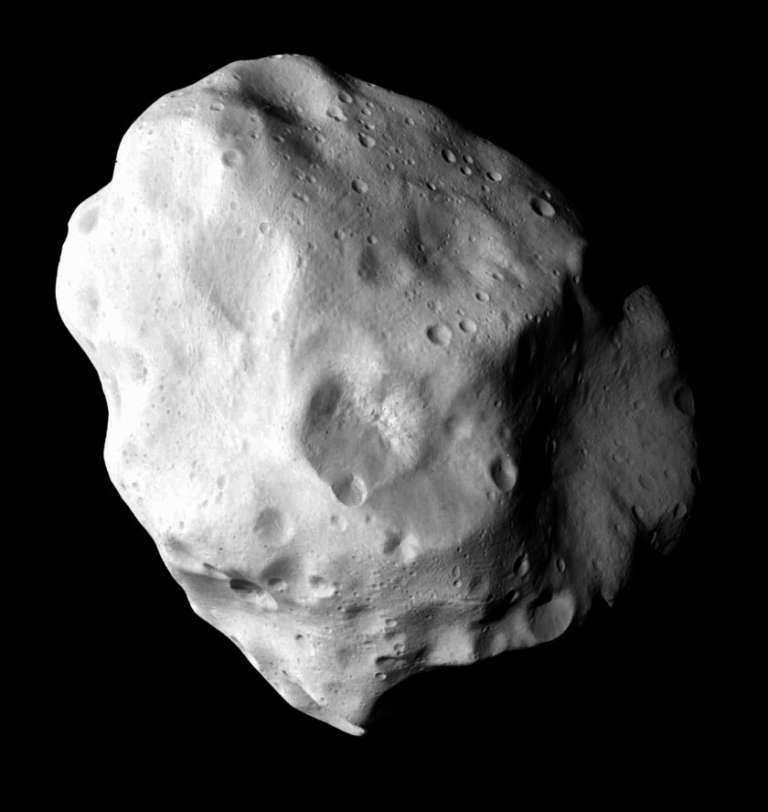

Now I have time to study them, and Lutetia is certainly a world different to other asteroids that have been visited before. Here is the last image (at least of the set released this evening by ESA) in which the entire body fit within the OSIRIS field of view; there are a couple more that are higher-resolution, but bits of the edge of the disk are clipped off. The version as released was a bit saturated in the most brightly sunlit areas, so I fiddled with the levels to bring out more detail there. That fiddling did make the dark parts of the disk a bit dim. It's hard to process a picture so that you can see detail everywhere.

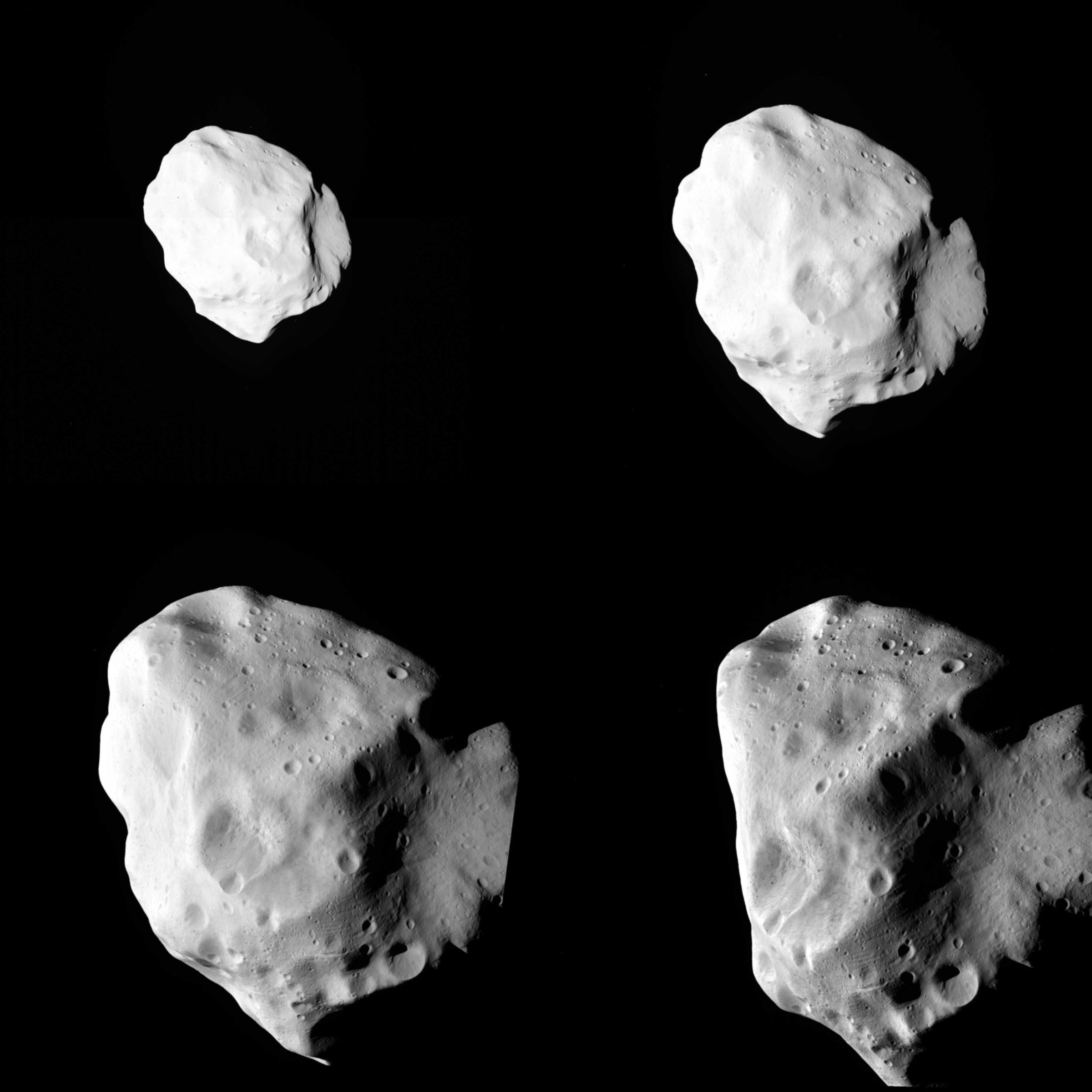

Definitely click to enlarge the photo. One thing that is wonderful about Rosetta is that unlike all the other framing cameras I know of that are flying in space right now, its CCD detector is capable of capturing photos two thousand pixels square. Other framing cameras, like those on Cassini, the rovers, MESSENGER, Galileo, and Voyager, have many fewer pixels, only a thousand or 800 pixels square. There is so much more detail in the Rosetta photos than I'm used to! Here's the montage I took it from.

Let's tour around some of that detail. The image to the left is five little postage stamp bits from the four high-res images they released, all at their full resolution, though the actual size of one pixel in meters on the ground at Lutetia differs from image to image because Rosetta's distance was changing from photo to photo.

The first photo shows a ton of nicely bowl-shaped craters, most with lovely raised rims, brought into stark relief by the oblique lighting near the terminator (day-night boundary). Is it my imagination, or do I see a sort of "bathtub ring" in the two largest craters, maybe even in the third largest crater, a line concentric to the craters' rims of slightly darker material?

The second photo is a bit just on the edge of the limb, a crater with an unusually dark patch of material around it. Is that fresh ejecta surrounding a relatively young crater? Or just a trick of lighting? Fresh ejecta is usually brighter than the surrounding terrain. Dark sprays of material, I associate with volcanoes -- on the Moon and Mercury anyway. I would have a tough time believing volcanism on a tiny old object like Lutetia so I'll look elsewhere for an explanation.

The third (middle) detail photo is the interior of a large crater. Black spots mark large (tens, hundreds of meters across) boulders. I don't think the boulders are inherently darker than the surrounding terrain: I think we are seeing their shadows, both their shadowed sides and the shadows they are casting on the ground. Smoother, boulder-free areas lack shadows, so appear brighter. Just below center is a patch that looks like a smudge in the image. That's no smudge; it's just an area of terrain that is smoother than everything around it, possibly because it is a relatively recent landslide. Note how this area is devoid of small craters; it must be a relatively youthful feature of Lutetia that hasn't yet been pockmarked by small impacts.

Compare that to detail #4, which is covered with small craters, and also linear grooves running left-right across the photo. Lots of small bodies, notably Phobos and Eros, display grooves like this. In fact, at first glance, you'd be forgiven for mistaking Lutetia for Phobos. The jury's still out on what exactly causes the grooves on these small worlds. I'm also interested in the elongate crater to the left of center. Did a little asteroid skip off the surface of Lutetia, bouncing away and leaving this elliptical skidmark instead of a round crater?

Finally, the bottom image: more grooves, but these appear strangely squiggly. I haven't the faintest idea what could cause that.

Fun! And we have yet to see color versions. Color images may possibly be available as early as Sunday (as I write this, I realize it is already Sunday in most of the world), but may not come out until Monday.

I can't complain about the image releases here though -- we got an awful lot of great photos, unprecedentedly quickly for ESA! They've got a small crew and they've done a great job. Many thanks to the ESA operations and OSIRIS teams for their quick work today, and congratulations to everyone involved in Rosetta for what was evidently a productive and successful flyby!

Goodnight, Lutetia. Farewell; I wonder when, if ever, you will be visited again by a spacecraft sent from Earth.

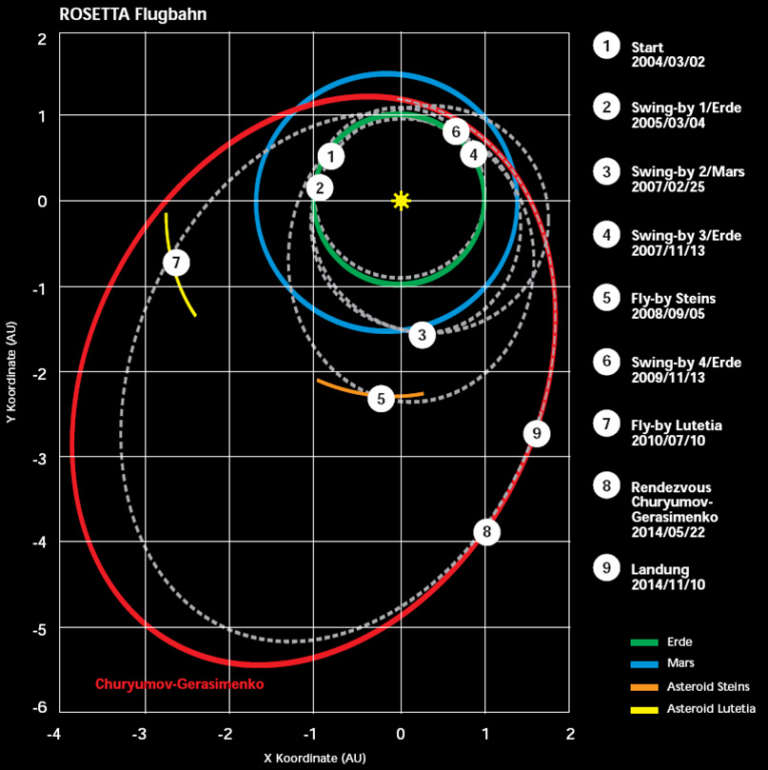

What's next for Rosetta? Believe it or not, there is not another thing in its path between now and its arrival, almost four years from now, at comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko, in May 2014. Beginning in July of next year, Rosetta will enter a very deep hibernation, sleeping away the subsequent two and a half years, before it finally wakes up to rendezvous with its first comet. In order to match paces with the comet, it must swing much farther from the Sun before approaching it again; that outbound swing will take it to such a great distance that even its enormous solar arrays will be insufficient to keep it ticking along -- thus the long sleep.

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth