Jason Davis • Aug 28, 2017

NASA considers kicking Mars sample return into high gear

NASA is considering a leaner, faster plan to retrieve samples from the surface of Mars.

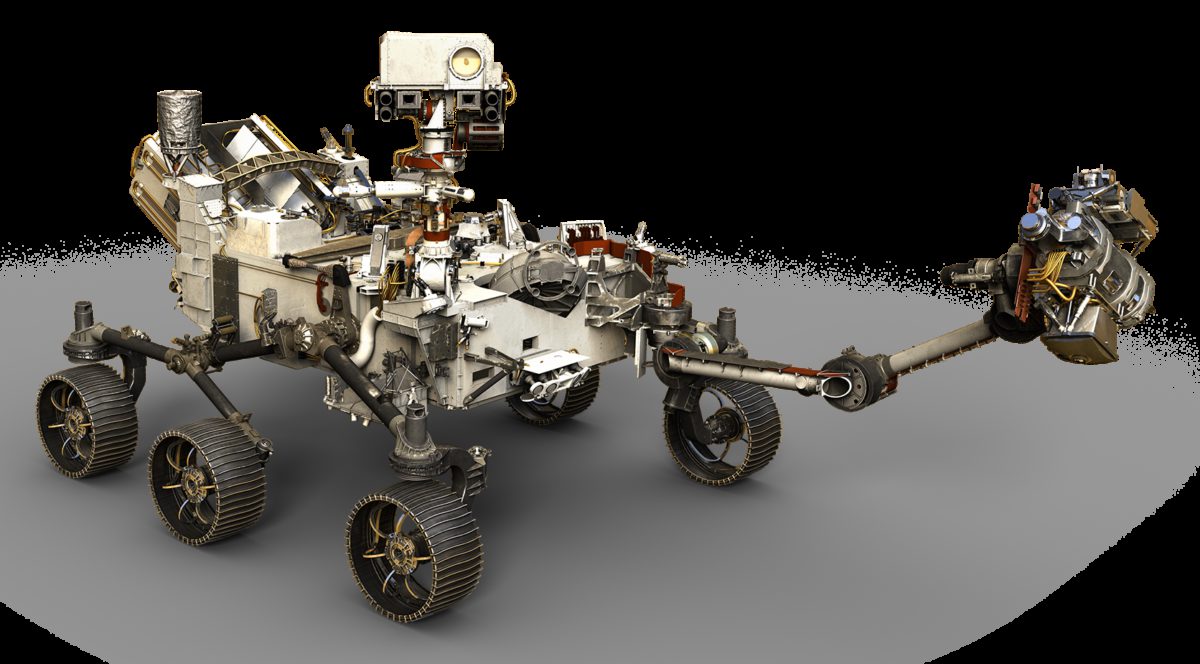

The agency's next-generation Mars 2020 rover, which arrives at Mars in 2021, will collect rock and soil samples and store them for future return to Earth. But thus far, no plan has solidified on how, or even if, those samples will be returned.

That is starting to change. At a National Academies space studies board meeting today, Thomas Zurbuchen, the head of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, outlined options for a future mission launching as soon as 2026 to retrieve the samples and blast them into Martian orbit. There, the samples would be transferred to another spacecraft and transported back to Earth, or possibly lunar space, where they could become part of NASA's human exploration plans.

Getting the samples back relatively quickly would represent a shift in focus for NASA's robotic Mars program. The all-in effort would likely backburner a new Mars telecommunications and reconnaissance satellite, owing to overall budget constraints.

"At the end, the question we're going to have to ask, is, 'How important is that sample return?'" Zurbuchen said. "Do we want to tunnel-vision focus on that piece, because of the fact that we think it's so critical?"

An exhaustive study of Martian samples on Earth would represent a huge leap forward in NASA's quest to learn whether life exists, or once existed, on Mars. Though modern rovers like Curiosity are miniature rolling laboratories, scientists say there is no substitute for in-depth, Earth-bound analysis.

How it would work

Mars 2020 is based on the Curiosity rover, and is equipped with upgraded versions of many of Curiosity's instruments. It launches in July or August 2020, and lands on Mars in February 2021. Three landing sites are currently being considered.

The rover's prime mission will last one Mars year—687 Earth days—though that is likely to be extended. During that time, Mars 2020 will use a drill to collect rock and regolith samples from various locations, focusing on rocks that formed in or were altered by water. Such rocks could contain signs of ancient organic life.

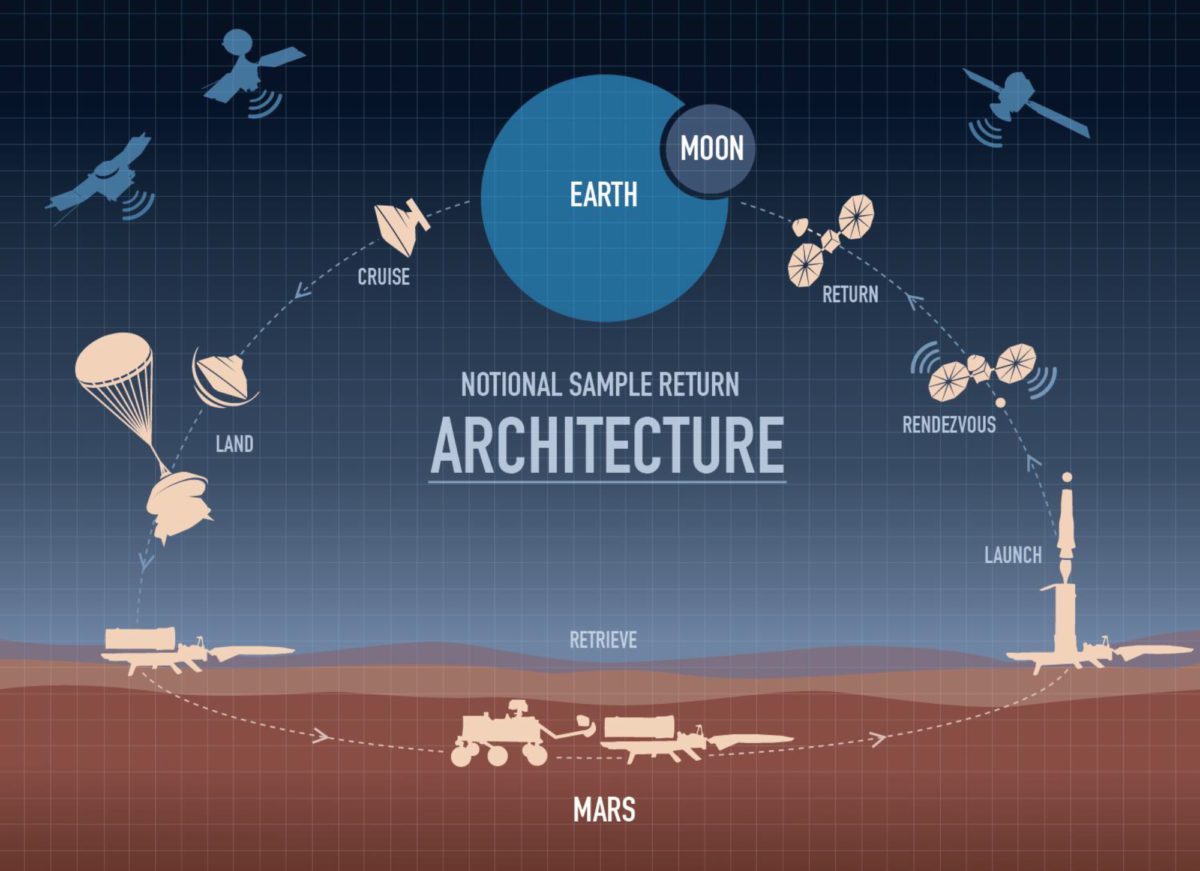

The samples will be deposited in easily accessible spots throughout Mars 2020's traverse path. No earlier than 2026, NASA would launch a retrieval mission to land in the same general area. The lander would either deploy a "fetch" rover, or rely on the Mars 2020 rover itself, to collect the samples and place them into a rocket on the lander's deck called the Mars Ascent Vehicle, or MAV. The sample-laden MAV would then blast off into Martian orbit.

High above Mars, the MAV-launched samples would rendezvous with another orbiter, which would pick up the samples for return to Earth.

Zurbuchen said NASA is considering international or even commercial partners to build the orbiter, providing necessary precautions are taken to prevent the cross-contamination of Earth and possible Mars microbes.

"The planetary protection piece is absolutely essential. Whoever the partner is, needs to share our values on this one—no compromise," he said.

The samples would either return directly to Earth or ease into the region around Earth's Moon known as cislunar space. NASA plans to start launching astronauts to cislunar space no later than 2023, using the Space Launch System and Orion crew capsule. The agency is also working on a small, Moon-orbiting space station known as the Deep Space Gateway.

That means the last leg of the sample return could involve astronauts.

"One of the tradable elements that will be really interesting to look at is that cislunar infrastructure, as that landing point or kind-of handover point for … these samples," Zurbuchen said.

Murky plans get clearer

The Mars 2020 rover was announced in December 2012. It was the top priority for the current decadal survey, which outlines planetary exploration priorities from 2013 through 2022. The report specifically said the rover should "collect, document, and package samples for future collection and return to Earth."

How to get those samples back to Earth, however, has remained murky. Since the rover's inception, NASA has hedged its bets when describing the return phase of the effort.

"It could potentially pave the way for future missions that could collect the samples and return them to Earth for intensive laboratory analysis," reads the official Mars 2020 website.

"It will also prepare a collection of samples for possible return to Earth by a future mission," said a February press release.

Complicating the situation further is that NASA's current Mars robotic program plan expired in 2016, a point highlighted by the Planetary Society in a recent report. That report urged NASA to craft a new strategy document, begin work on a new telecommunications and reconnaissance orbiter, and develop a way to get the Mars 2020 samples back to Earth.

In July, the House of Representatives' version of NASA's proposed 2018 budget included $62 million for a new telecom and reconnaissance orbiter to be launched in 2022. The Senate suggested an addition of $75 million to the robotic Mars program, but did not specify its use.

The final budget compromise could see the telecom orbiter de-prioritized, with the money being used for the sample return mission. One independent review of NASA's expected contribution estimated a cost of $4 billion for a lander, fetch rover and ascent vehicle. Subsequent studies came up with lower price tags, but there is no doubt the effort will be complex, requiring a significant amount of new technology development.

Without a next-generation telecom orbiter, NASA will need to look for other options to support its surface vehicles throughout the 2020s. The agency is considering moving the MAVEN spacecraft to a more favorable communications relay orbit. The European Space Agency will also contribute by way of their Trace Gas Orbiter spacecraft, TGO, currently at Mars, which carries a NASA-built communications package to provide fast relay capabilities.

Neither MAVEN nor TGO will provide optimal communications passes, but NASA may be betting the scientific community will work around those limitations in order to advance the community's top goal of a sample return.

Next steps

If NASA intends to launch the sample return mission in 2026, it needs to start to work on the project soon.

NASA's planetary science division is already developing two high-cost missions: the Mars 2020 rover and Europa Clipper. A third, a Europa lander mission, is in the early conceptual design stages, but the agency has yet to commit to the mission. Adding a flagship Mars sample return mission to the mix will be a budgetary challenge.

The payoff, however, could be huge. Signs of ancient life on Mars could be one of the biggest discoveries in human history. Today's announcement signals NASA and Zurbuchen are considering pulling out all the stops to deliver on the science community's highest priority.

"Depending on what's in these samples, we will think differently about nature and ourselves," said Zurbuchen. "Nature will always surprise us."

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth