Heidi Hammel • Sep 04, 2012

Following up the dark spot on Uranus

It was a surprise and delight to have our Icarus paper highlighted in Emily Lakdawalla's blog. Thanks for highlighting Uranus, since it has gotten, ahem, a bum rap over the years. (You have no idea how hard we tried to come up with a paper title that did NOT say "dark spots on Uranus.") A couple of grace notes.

It was Larry Sromovsky's surprising discovery at the Gemini Observatory of the extraordinarily bright feature in October 2011, followed by valiant efforts of the world's top amateur astronomers to image that feature, that allowed me to trigger the Hubble observations.

Had the feature persisted in -- or increased beyond -- its October brightness level, there's a chance that more amateurs might have seen the feature. Unfortunately, it faded.

The Keck images on 10 November, while good, were not excellent due to a mis-aligned lenslet array in the adaptive optics system. In fact, we at first thought the two features were really just a horrible image of a single feature. The (still poor) images on 11 November continued to show two features, however, and it was clear they had moved relative to one another. The lenslet array was corrected and the images were exquisite but...on 12 November the feature was on the other side of the planet, and our time over. We pleaded with the next observer, Bill Merline, to please please get us a picture of Uranus on 13 November, which he graciously did, and that allowed us to definitively identify and track the features.

The team continues to hotly debate whether in fact there are two dark features that interacted. The data are right at the edge of having adequate signal to discern this, so we simply are not sure. We either need Uranus to increase the size or contrast of its features, or build bigger telescopes like a 30-meter, or we need a mission to the planet. I'm working on the latter two; the first is up to the planet.

The Voyager Great Dark Spot on Neptune does actually also look like a hole in a higher cloud deck. But the shapes of the Uranus dark features, and their contrast as a function of wavelength, seem to differ from those seen on Neptune. Again, however, we are stymied by the limitations of even the very best telescopes on Earth and in space, because these ice giants are so far away that their disks are extremely tiny. It is soooo frustrating!

When we first saw the Hubble images from 25 December 2011 and, like you, saw nothing particularly outstanding, there was a lot of email circulating about our Christmas "lump of coal." But then, when we looked more closely and found the dark feature, we celebrated that this black spot was a pretty nice piece of coal, indeed. One of the team members, Wes Lockwood at Lowell, subsequently sent me one of those little bags of "Santa's coal" black chewing gum, to "share with the team the next time we are all together." Maybe we will do this at the Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting in Reno.

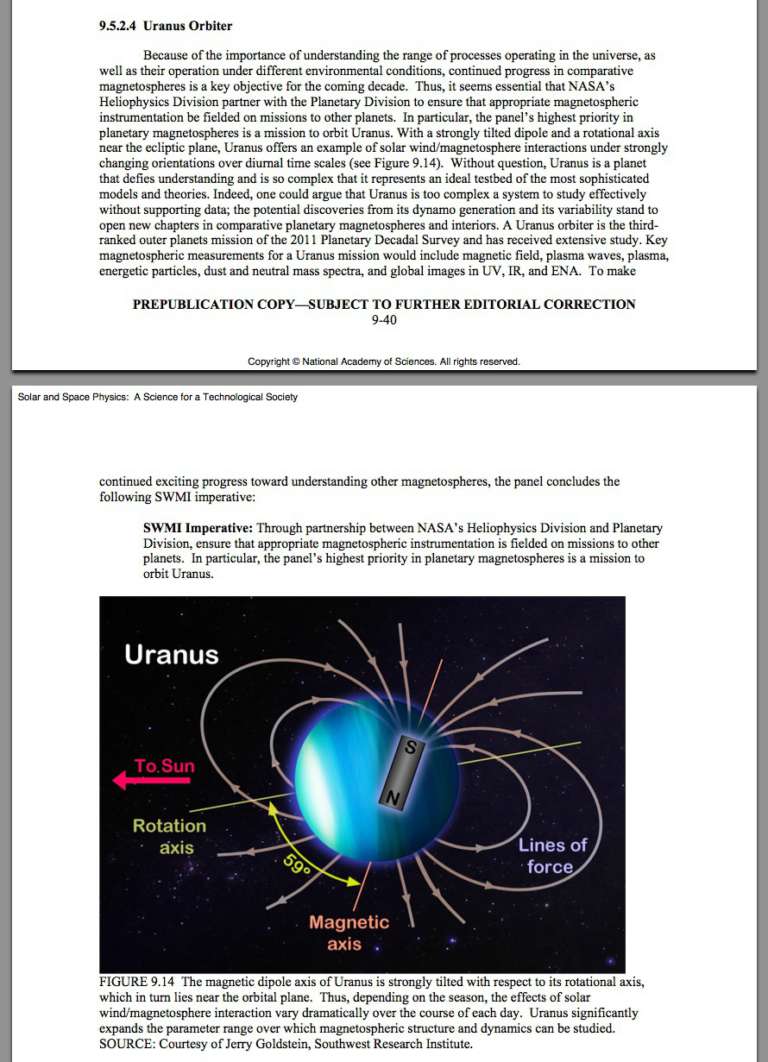

On a related subject, I just discovered that the very recently released Solar Physics Decadal Survey endorsed a Uranus mission (!), and most astonishing was that I had absolutely nothing to do with that endorsement. So gratifying that people besides me DO recognize the importance of ice giants...

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth