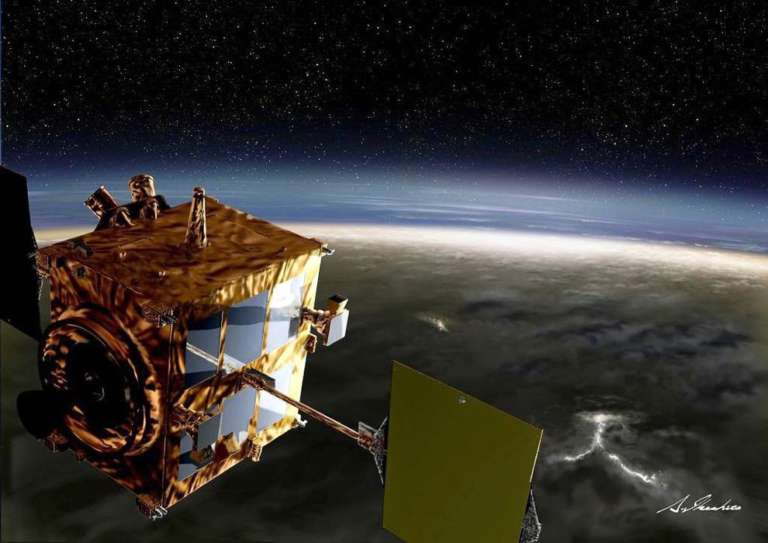

Akatsuki, the Venus Climate Orbiter

Highlights

- After an engine failure scuttled its first attempt to reach Venus in 2010, Japan's Akatsuki mission finally entered orbit around our neighboring world in 2015

- Its main goal is to figure out how the Venusian atmosphere works and why it rotates so quickly around the planet

- Akatsuki may have spotted the first hint of lightning there, which has been suggested by other missions but never actually seen before

What is Akatsuki?

Launched on May 20, 2010, Akatsuki — also called Planet-C or the Venus Climate Orbiter — is the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) first successful mission to another planet. It faced its first major hurdle just months after launch when the craft’s thrusters fired for less than three minutes instead of 12 due to an engine failure. It did not enter orbit around Venus in December 2010 as planned and instead remained in orbit around the sun in hibernation until 2015, when JAXA engineers were able to fire the thrusters up again and put the spacecraft in its intended orbit around Venus.

Since then, it’s been mostly smooth sailing for the orbiter, although some of its infrared cameras did shut down at the end of 2016. It is in an elliptical orbit that brings it just 400 kilometers (250 miles) from Venus’ surface at its closest, and takes about nine days to circle the planet.

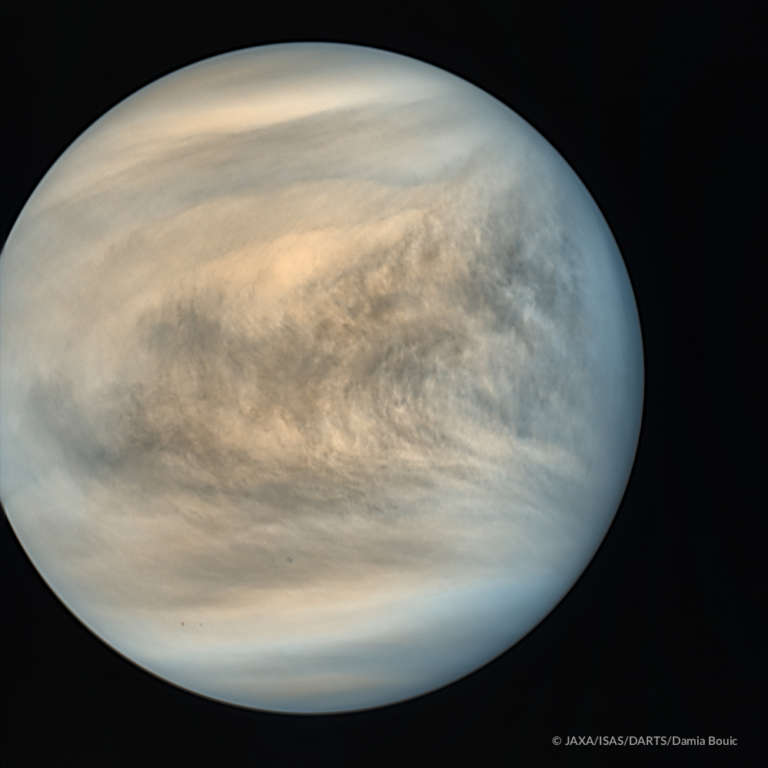

The mission’s main goal is to understand the dynamics of Venus’ atmosphere: it rotates faster than the planet’s surface — a phenomenon that has not been fully explained. The same is true of the planet’s thick clouds of sulfuric acid and the lightning that may flash within them. Akatsuki is also searching for Venus’ “unknown absorber”, a mysterious component of the atmosphere that is responsible for absorbing the majority of the solar energy the entire atmosphere takes in.

How Akatsuki works

The spacecraft itself is a box measuring 1.45 by 1.04 by 1.44 meters (4.8 by 3.4 by 4.7 feet), with solar arrays on arms protruding from two of its sides. The solar arrays power the scientific instruments, and the twelve thrusters that control the craft’s orbit and position are powered by liquid rocket fuel.

Akatsuki has six scientific instruments. The first, the ultra-stable oscillator, generates radio waves. When the spacecraft is behind Venus as viewed from Earth, these radio waves skim through the Venusian atmosphere before reaching Earth, changing their frequencies in a way that allows us to measure how the atmosphere changes at various altitudes.

All five of the other instruments are cameras, observing at wavelengths ranging from the ultraviolet, through the visible, and into the infrared. The camera that uses the farthest-infrared wavelengths uses them to measure the temperature at the top of Venus’ clouds, which can also help us understand how the upper cloud layer is moving and mixing. The two other infrared cameras failed in 2016, but before then they were used to peek deeper into the clouds and examine the heat radiating from the planet’s surface.

Finally, the images in visible light are used to look for lightning, which had not been definitively detected on Venus before. They also capture oxygen in the upper atmosphere, which glows and allows researchers to track the air’s movement during the Venusian night.

Major discoveries so far

Akatsuki made its first discovery just hours after it entered orbit around Venus in 2015, when it spotted a huge curved feature in the planet’s atmosphere. This enormous curve stretched nearly all the way between the north and south poles, and despite the strong and fast winds, it remained still above an area called Aphrodite Terra.

Later observations showed that such “sideways smiles”, as some described them, appeared regularly over several tall mountains on Venus, and stuck around for about a month once they popped up. Researchers concluded that they were caused by gravity waves, which are ripples in an atmosphere caused by air moving over rough topography — not to be confused with gravitational waves, which are ripples in spacetime. This would later prove to be just the first in a series of strange waves that Akatsuki saw rippling through the Venusian atmosphere, many of which uncovered more mysteries than they solved. For example, the gravity waves over mountains seemed only to appear at high altitudes, not closer to the ground.

Akatsuki also spotted a jet stream blowing at extreme speeds around Venus’ equator in the lower layers of clouds, which could explain some of the strange shapes and vortices that have been observed there — although jet stream itself has not yet been explained. The team has produced 3D maps of the atmosphere, though, including the temperature and pressure of the air and some of its constituent parts and how they change over time.

After years of hunting for lightning, the spacecraft finally found a signal in March 2020. This single flash of light on Venus’ dark side could have been either lightning or a meteorite burning up in the planet’s atmosphere, but if it is lightning it would be the first time we’ve actually seen it on Venus.

Support missions like Akatsuki

Whether it's advocating, teaching, inspiring, or learning, you can do something for space, right now. Let's get to work.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth