Planetary Radio • Jan 07, 2022

Space Policy Edition: What We're Watching in 2022

On This Episode

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

New rockets, new legislation and a new direction for planetary exploration are just some of the major events happening in space in the coming year. D.C. operations chief Brendan Curry returns to the show to explore these and other issues that will shape the next decade of space exploration and occupy The Planetary Society's advocacy and policy team in 2022.

Related Reading and References

- The 2022 Day of Action

- Space SPACs look to rebound in 2022

- Biden Commits to ISS Through 2030 Amid U.S.-Russian Tensions

- The Search for Life as a Guidepost to Scientific Revolution (Planetary Society’s submission to the planetary science decadal survey committee)

- Increasing the Scope of Planetary Defense Activities: Programs, Strategies, and Relevance in a Post-COVID-19 World (PDF) (Planetary Society’s submission to the planetary science decadal survey committee)

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Welcome, everybody, and Happy New Year from the Space Policy Edition of Planetary Radio. We are very happy to have you back for yet another year of this monthly look at everything that is happening on the policy side of space exploration, policy and advocacy. We're going to start this year with a show that looks forward across what's coming across 2022, and I am delighted to be joined by my two wonderful colleagues who are most closely involved with this work on behalf of The Planetary Society. I'll mix it up a little bit and start this time with you, Brendan Curry, Chief of Washington Operations for The Planetary Society. Welcome back to SPE.

Brendan Curry: It's great to be with you guys.

Mat Kaplan: Of course, with me for every one of these shows and largely carrying the ball is the Chief Advocate and Senior Space Policy Advisor for the Society. Casey Dreier, Happy New Year to you as well.

Casey Dreier: Oh, thanks, Mat, and always a delight to start another year. I just want to say, putting this show together, doing a little work, there is so much happening in the next 12 months in space. It makes me sound like an old person, which I am rapidly becoming, but I start to think about, "Wow, when I started working in this business, everything was delayed and slow and nothing was happening, and now there's almost too much to keep track of." So it's truly exciting and a delight to talk about this. It was hard to select a subset of things to discuss what we're most looking forward to. So it's great and excited to be here and to share another year with you, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: I'm almost tempted to share the list that the two of you came up with because we're not going to get to everything on this list, but it's an impressive list. Of course, there are things that are happening even as we speak because, as we speak, the James Webb Space Telescope, the JWST, is performing beyond, I think, the belief of even the people who built it. It is absolutely thrilling to watch that mighty new telescope unfold in the sky. Casey, you were just telling me... I missed it because apparently it just happened in the last hour as we speak, but apparently the secondary mirror is now locked in place.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. They're, I think, 80% through the deployment sequence of everything must having to work through this process. I'll just say straight out, we're just going to accept that JWST is one of the most important things, and then we'll talk about everything else we're looking forward to in the future in the show. But, here, can you hear this? That's me-

Mat Kaplan: Wood?

Casey Dreier: ... knocking on the closest thing I can find to wood. It's truly amazing to see how smoothly this process has gone so far, the unfolding, the tensioning of the sun shield, the deployment of the mirror. Of course, the optics all have to work, but I keep thinking about how the process of this and why Webb was delayed, the cost versus the original projection, and you see in a sense the incentive structure paying off here, that NASA... It's easier for NASA to take a mild political hit of going back to Congress, hat in hand, and asking for more money and saying, "It's going to be delayed," in order to ensure that we get this deployment sequence working correctly.

Casey Dreier: Think of the political fallout if the sun shield hadn't deployed or someone forgot to remove the right firing pin or installed it backwards. There would be consequences for years and a black eye on NASA's reputation. You pay the money in advance, and then it more than pays off politically in the future, right? Nothing succeeds like success. The incentive is for NASA to do the work it takes, to do the engineering, to do the failure analysis in order to get these 0.9999 percentage confidence levels for these massive programs. It costs money to do that. But at the end of the day, no one is sitting here grousing about the extended cost of the Hubble Space Telescope. People are just enjoying the Hubble Space Telescope. It's going to be the same with JWST.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, I cannot help but think back to those days when it looked like there might not be a JWST because it was in such trouble and Congress was essentially prepared to cancel it out. I mean, it's so good to see this happening now. Of course, I don't want to count chickens because we're not there yet. We still have months of preparation of the telescope before it starts its work.

Casey Dreier: That's why I knocked on that wood.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. I got some here, too.

Brendan Curry: It's certainly been a saga, obviously, as Casey mentioned, from a technical standpoint, but it's also been a saga politically. To get congressional buy-in over many Congresses and have many administrations still want to be committed to such a grandiose mission still says a lot about the political appetite that both parties do have for space exploration in the advancement of science and American space leadership. So everyone's knocking on wood right now. When this thing got starts transmitting data and we find out things we didn't even think we were going to discover, this very well could be one of those missions where success has many fathers.

Casey Dreier: Brendan, I was going to ask, where were you in 2010 when they proposed to cancel the mission in the House appropriations bill?

Brendan Curry: I was at an organization called Space Foundation, and one of our corporate members was Northrop Grumman, so I worked with their DC team to help in my own small way. But in earlier iterations of the times this mission had a couple near death experiences, I was a staffer on the Hill, and we worked to keep it alive. It's been an interesting experience because I think a lot of folks on this... As we were gearing up for the launch on Christmas day, a lot of people still had PTSD from the deployment of Hubble and the problems that mission had almost from the get. Everyone is just ecstatic. As I mentioned to you gentlemen before we went live, I was on a group call with Michelle Thaller at Goddard. She was just giddy about how this deployment is going not only faster but smoother and better than anyone over at Goddard ever thought it would. So a lot of hurdles to still jump through, but so far so good.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. It's just wonderful. And, again, I keep thinking about the irony in the sense of all of us knocking on wood or crossing our fingers. Probably, someone out there is wearing a lucky rabbit's foot or something. We all know it's kind of insane to think that way, but, at the same time, it's something active we can do to express our hope and desire that something will work. It's been truly exciting to watch, and I've just been so happy to see the team succeed and all that hard work paying off so far. Also, I wanted to say a kudos to NASA and the team for being so open with the whole process. They're starting to do live broadcasts from the mission control center at STSI showing their various deployment aspects. This is the essence of... It's a public space program. They're being public about it. They're putting themselves out there. Failure is a possibility, and they're they're nailing it. So it's just very... Good on them.

Mat Kaplan: And they have been terrific with us, enabling us to talk to people behind the telescope. We're going to be using the telescope on Planetary Radio. Of course, there will be much more of that to come. Hey, Brendan, thank you for your service back then. You had a part in all this, apparently. I'll just leave it at that.

Brendan Curry: Very small.

Mat Kaplan: Every little bit counts, and every little member counts. They're all big members of The Planetary Society. How's that for a segue?

Casey Dreier: Great segue.

Mat Kaplan: You knew that the pitch was coming, right, planetary.org/join to become a part of this organization that employs these two guys, Casey and Brendan, keeps them busy in Washington, DC, and elsewhere, and making sure that projects like JWST are able to move forward and get that bicameral, bipartisan support from Congress and elsewhere. We hope that you will join us and make your influence known in Washington, DC. Casey, there's another way for people to make their influence known and felt in Washington, DC. Day of Action is coming again.

Casey Dreier: It is. March 8th, 2022, we're doing our second virtual Day of Action for obvious reasons, and you can register. If you want to level up your advocacy-ness, if you want to engage directly with your representatives and their staff in Congress, if you want to work with and meet fellow members of The Planetary Society who are as dedicated as you to enabling the future of space exploration, this is for you. The Day of Action is at planetary.org/dayofaction. Register online. We train you on a three-hour training session on Sunday prior. We set up meetings for you with your representatives and representatives in your state. We give you talking points, we get practice, we prepare you to be the best advocate you can be, and you are doing that direct advocacy to the people who make the decisions.

Casey Dreier: This isn't just me claiming this. It's not just Brendan claiming this. There are studies done of Congressional staff saying, "What is the most influential act you can take as a citizen to influence the decision process of your representatives," and it's this in-person direct advocacy. It really does make a difference. So if you are interested, and, again, if you've never done it before, it can be a little intimidating, we help you through that, and people who've done it almost universally are thrilled to have done it, feel great about doing it, feel empowered afterwards. It's really exciting to watch. So planetary.org/dayofaction. Check it out.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, you have sat on both sides of the table in those congressional offices. I guess you can also attest to the effectiveness of this kind of personal action.

Brendan Curry: Yeah, it really does make a difference. It's one thing if you're a congressional staffer and you routinely see professional lobbyists coming in advocating for their clients or the corporation they work for. But when you have constituents coming in who are taking the time to talk to you about something that means something important to them, there's a personal impact to it. There's almost an emotional resonance that you get from hearing from your constituents talking about something that they care about.

Mat Kaplan: Let's continue over the course of the rest of this Space Policy Edition. I know that each of you have selected a few of the topics from this long list that you created, and we're going to dig into these somewhat. There is, as I said, far more to talk about than we'll be able to cover. Casey, let's start with you.

Casey Dreier: All right. So I chose three topics that I'm going to be very interested in following next year that I think will have broad impact and consequences at the policy level and, of course, just general engagement with space in the industry. Brendan chose three, and we're going to share them one at a time, I'd say in no particular order because they're hard to prioritize because they can be all so different. So I'm just going to choose one at random, and I will start this discussion for 2022.

Casey Dreier: What I am most eager to see and I think potentially most impactful for the year and the years ahead is this new crop of launch vehicles that will be having their first launches, their demonstration launches in 2022. There's a bunch of them, and I think it's representative of this revolution that's happening or at least this evolution in launch vehicle capability that's going to open up access to the cosmos throughout the world in this next decade and the decade after. Obviously, there's Artemis 1, with the first launch of the SLS rocket. That's a huge one in terms of reputational ability for the SLS. This has to succeed. It's also the only way that NASA's planning to send humans to the moon for Artemis, so there's no backup to this.

Casey Dreier: We're also looking at Starship, this potentially revolutionary new super heavy lift, fully reusable mega rocket that is going to be not just land... It's not going to land. It's going to be caught by these so-called chopsticks in the launch tower in order to save that extra weight on landing capability but also, again, could theoretically lower the cost of mass to space by orders of magnitude. We're seeing Ariane 6, the European Space Agency's new version of Ariane. Ariane 5 launched the James Webb Space Telescope. That was one of the last or the very last launch of that rocket. The 6 is the new path for Europe. Then, of course, Blue Origin and Vulcan by the United Launch Alliance, its response to the Falcon 9.

Casey Dreier: So there's all these new launch vehicles coming online in the next year, supposedly, or the year after that, and I was trying to think about some metaphor that would help place this into why this is important from a policy perspective or even just a space perspective. You can tell me what you think about this metaphor. It's almost like the equivalent of Apple and Google and Samsung releasing new cell phones, right, that these are the hardware platforms upon which the access to space happens. They set the boundaries of what you can build and where you can go and how much resources you need to get there. So if you're seeing these continued revolution or evolution of these hardware platforms of launch vehicles, the types of spacecraft you can fit on them or the number of spacecraft you can do based on their price, it's highly deterministic, these enabling factors, for the future of space exploration.

Brendan Curry: And I would just add that the Chinese are planning to fly upgraded or new iterations of their Long March launch vehicle as well. So they're not sitting on their hands either.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, there's also Rocket Labs is pursuing... I mean, some won't happen this year. There's also Blue Origin's New Glenn, and if you look at where money is going in commercial space flight investment, the vast majority of investment is going into launch vehicle companies. So this is the big practical sector. Of course, you have these other relationships to mega constellation deployments, right, of low earth orbit satellites. Everything is about access to space. Again, we're seeing this vibrance and vitality in the sector. I don't know if... Have we ever seen this? Not since the '60s, but that's hard to compare because that was also closely tied into national security needs and development was not happening through these commercial companies. It's truly exciting.

Casey Dreier: Again, I think trying to frame this as a way of this is a deterministic output where the types of rockets you have set the capabilities and the number of missions you can do... We saw the launch of IXPE, this small x-ray astrophysics satellite last year, and it launched on a reusable Falcon 9 for $50 million. An equivalent launch on an Atlas 5 would be about $150 million, right? So you're talking about a savings on the order of half the cost of a new small astrophysics mission, Europa Clipper launching on a Falcon Heavy that will cost literally a fraction of the nominal cost of an SLS. So you're talking about the difference of one New Frontiers mission of cost because the Falcon Heavy was there as an alternative to the SLS. So this is not just the fact that you can have the hardware capability, but if you're driving down cost with this competition, you're saving NASA and other agencies hundreds of millions of dollars that then can actually be used for real missions. I think we're seeing the consequence of that will begin to continue to multiply as we go forward with this bevy of new vehicles out there.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, you noted that the Long March vehicles, including China's development of a super heavy of its own... That may still be a few years away. But I keep seeing these announcements of small, I'll put it in quotation marks, commercial companies in China developing small launchers, commercial launchers. That, of course, that proliferation happening in the United States and the UK, almost you name it. It seems to me that there's going to be some market pressure here, some good old supply and demand that is going to, one would hope, continue to force down the cost of getting stuff and hopefully also people up into space.

Brendan Curry: That's where the Wild Wild West is right now. A lot of these, at least on the Western side, they're looking... When they think about SpaceX, everyone's thinking about the Starship and the Falcon Heavy and things like that. But SpaceX didn't start out with those vehicles right out of the gate. They had a very small vehicle called the Falcon 1, and I think you have a lot of folks who are trying to maybe not copy but at least mimic or do some lessons learned from the early days of SpaceX and go along with that. On the US side, a lot of these smaller guys are looking to get contracts from the Pentagon. The Pentagon's trying to be a little bit more innovative and not always defer to what we call a Battlestar Galactica type satellite for use by the NRO and that the advances you've been seeing in the miniaturization of things that you can put on smaller satellites, they don't need bigger, ergo more expensive, launch vehicles, that they can execute a mission with a smaller payload on a smaller vehicle.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. I think of Virgin Orbit as a good example of this, which has been picking up some government or defense contracts. A pretty small rocket hung under the wing of that 747. Who knows which of these will actually be successful in the long run and deliver to their investors? But they're sure all in the game.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, and I think it's important to flip this around and not just say that we're looking toward the success of this, but, also, why this is important is the implications of failure are significant, and I'd say particularly for the SLS getting off the ground this year. Showing that that program, after however many tens of billions of dollars has been spent on it, is going to be capable of delivering on its promises is very big, and particularly for the SLS, which has a very slow build time. The consequences of failure will resonate if it fails for years in advance because it's going to take time to build the second one, to prep the second one. Everything would get pushed back.

Casey Dreier: For Starship, too. NASA, don't forget, is now a co-investor in Starship. We saw finally NASA has committed $3 billion to modifying Starship to land on the moon. They as a space agency, we as a nation in the United States, are now committed and invested in seeing Starship succeed because it's going to be key toward lunar landing plans now as well. Let's not forget, this is not a foregone conclusion that it will work. You had Elon Musk going on Twitter a month and a half ago, six weeks ago at this point, saying that there's some significant issues with the manufacturing process behind the Raptor engines and the very real consequence of potentially bankrupting SpaceX in 2022.

Mat Kaplan: Exactly what investors want to hear.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Well, not just investors. It's literally the case that Blue Origin was making to Congress of why you need a second human landing system selection. It feeds into all this uncertainty, and it reminds you that SpaceX is still bound by physics or bound by... It's a challenging problem. We're used to them succeeding. It doesn't mean they were always succeed. When you talk like that, I think it's important to remember that NASA needs to build in resiliency to its program when you're going through these kind of commercial contracting solutions where, in a sense, you're no longer...

Casey Dreier: We talked about how NASA paid for that extra 0.99999 percent assurance on James Webb at the beginning of the program. That's not what you do with commercial space flight. You get resiliency by having multiple providers. You're not committed to ensuring that one program will work. That's the risk that NASA takes. It's a programmatic risk while securing cost risk. It's just a reminder, and I think we should bear in mind the consequences of failure. I'm glad that SpaceX is swinging for the fences here, but, at the same time, it will have significant resonance through, again, the future, in a similar way that the SLS failure would have, if SpaceX is unable to deliver on its promises.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, let's go on to the first of those three topics that you've chosen that we hope to address today. Where do you want to start?

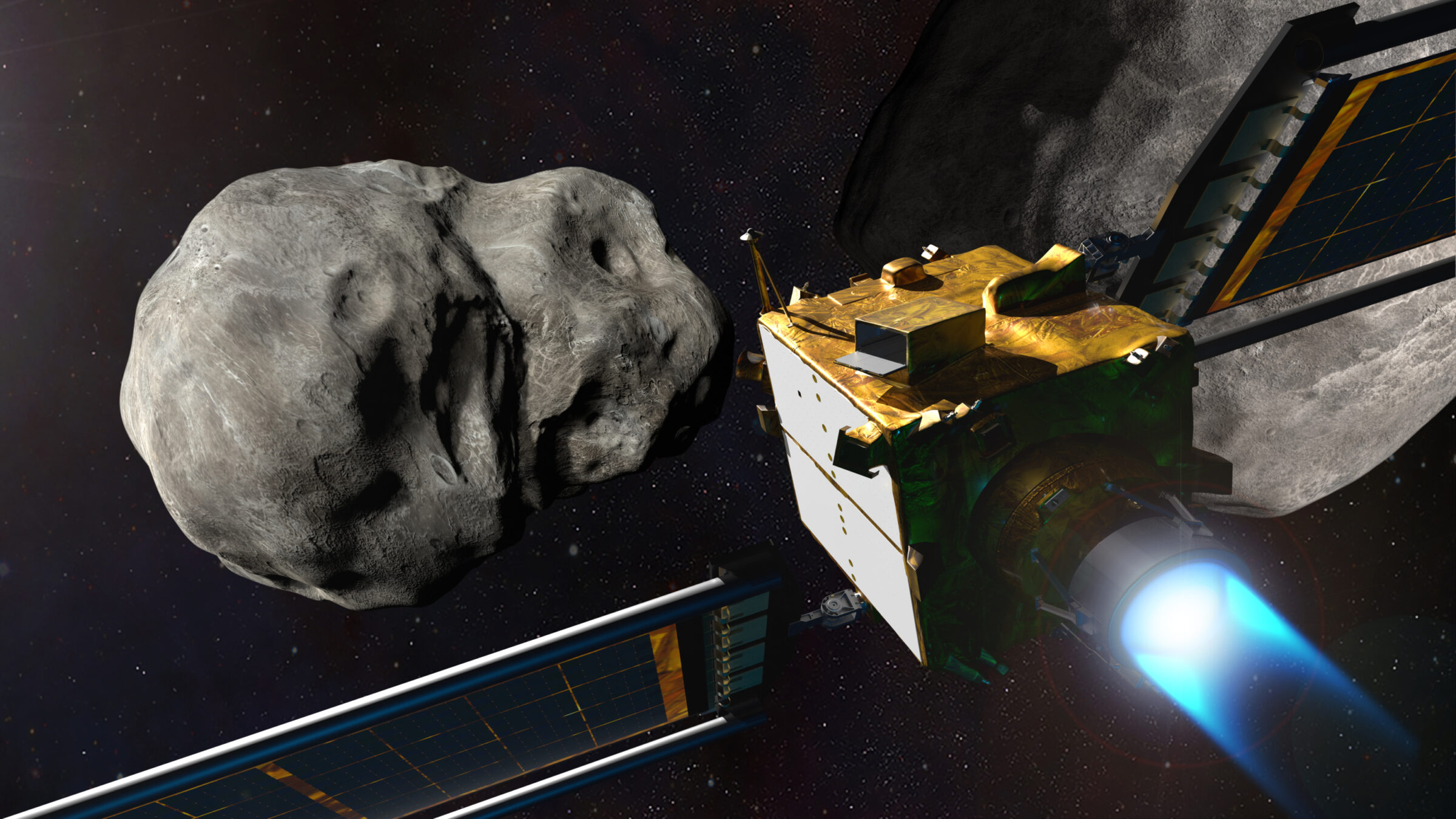

Brendan Curry: I want to start off with DART. Personally, I think it's a super cool mission, and it's a mission that's close to the heart of our organization. It's already on its way, and it's going to rendezvous or impact, however you want to call it, with its target asteroid around the September timeframe. It was one of those missions that didn't cost a ton of money. It was essentially on time, on schedule. It has an international component. There's going to be an imaging micro sat that it's going to deploy from it to image the impact that the main vehicle will have on the satellite. So I always like seeing where we can work with our international friends and allies on space. I think everyone involved with that can't help but think of the Bruce Willis mission, as bad as the science was on that movie, but it's just another example of our science and technology being employed to do cool things but also have a direct benefit that normal everyday people can understand.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you for the opportunity to drop in yet another plug for Don't Look Up, where the science is much, much better. DART, of course, the Double Asteroid Redirect Test. That little CubeSat, I think, is from the Italian Space Agency, and then there's the European Space Agency's follow up mission, Hera, which is... Do either of you remember how much longer after DART's impact it-

Casey Dreier: '26.

Mat Kaplan: '26. Okay. To take a look at the long-term effects of that effort,

Casey Dreier: The big picture here, right, we talked a little bit about with Lindley Johnson, the Planetary Defense Coordinator at NASA, is that DART represents... It's not just the mission. I think there's a symbolic value of DART. It's the first dedicated planetary defense mission that NASA has ever done. NASA is a mission-based agency, and I think there is a certain level of respect a program gets when you are launching missions versus not, just in terms of conceptually how it's seen within the agency, from congressional supporters. To see planetary defense move into this new era of being a mission-based program, not just running ground-based telescope observations or running little telescopes, it has a new cache to it, I think, that's really important symbolically and opens up this door for our future missions, like NEO Surveyor that is going to go out there and look for these dangerous asteroids.

Casey Dreier: Mat, I was actually kind of curious. As someone who's interviewed Amy Mainzer, of course, our friend who works on NEO Surveyor, the science advisor on Don't Look Up, but also the director of Don't Look Up, how do you think DART is going to be seen now that... Don't Look Up, I saw, was the most watched program on Netflix maybe or the most watched movie. It was very, very popular. Do you think people will see DART differently now with this movie out?

Mat Kaplan: I don't think there's any question about it, and I think that that airburst over Pittsburgh on New Year's Day probably didn't hurt either. We're going to keep getting these little reminders in the sky now and then of how important this priority is. So, yeah, there's no question. I'm sure DART is going to maybe have as big an audience as Don't Look Up has had when we have that coverage of the impact. Brendan, I know you want to jump in, but I'm also just wondering have you seen the attitude in Congress toward planetary defense evolve with some of these recent actions?

Brendan Curry: Yeah, I have because for a while it seemed kind of remote, esoteric. There was even somewhat of a giggle factor. The fact that this mission is now underway, and, again, cross our fingers that it does what it's supposed to do, like Casey said, success will breed future success. There'll be more interest in trying to do other test missions like this to ensure that we don't end up like the people in that movie.

Mat Kaplan: Don't give away the ending. There are people who still haven't seen it.

Brendan Curry: Yeah. The other thing that's interesting about DART is that a lot of the sensor discrimination technology to make sure it flies in on target has its technical origins in the Missile Defense Agency. So this is, again, another example of the shared workforce, shared industrial base between the civilian side of space and the national security side of space and how they can help each other out.

Casey Dreier: Something that's interesting. I was thinking about also the value of Don't Look Up. The movie can be seen and is meant to be seen as an allegory, right, for or climate change, pandemic, and a variety of our institutional rigidity failing or preventing rapid response to a big problem. But missions like DART show that it is possible institutionally to change and adapt. That's something we talked about when we had Lindley Johnson on, that it's taken a few decades, but we only have to remember the concept of the threat of asteroid collisions with Earth is a relatively new science, right? It's only in the last 50 or so years that we've really established this as possible. Of course, Gene Shoemaker of the Gene Shoemaker Grants helped establish that it was impacts that created the craters on the moon and the craters we see on Earth.

Casey Dreier: That was in our lifetimes of a lot of people. It's taken a while. NASA was never created as a planetary defense agency. It had to change, and Congress mandated it to change. It updated NASA's charge to incorporate that. So DART, again, symbolically is a demonstration of our legislative and political systems, our policy systems, adapting to new information and reacting to it in a positive way. So, in a sense, it's a bit of a counterpoint to the absurdist cynicism of the movie. But, also, I think, if nothing else, the movie can work on the level of increasing awareness for the surface level reading of it, which is comets and asteroids are a threat to Earth. I talked to someone literally last night who was just learning about the threat of asteroids by watching that movie and didn't realize that the Planetary Defense Coordination Office represented in that movie was actually a real thing at NASA. That was a really interesting conversation. If nothing else, even if people don't read the subtext of the movie, the text of the movie is useful and valid in terms of how we approach the threat of asteroid and planetary defense.

Mat Kaplan: I am dying to ask Lindley Johnson next time I talk to him about his reaction to the depiction of his office at NASA, the Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

Casey Dreier: His office came out pretty well, I'd say, compared to some.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, absolutely.

Casey Dreier: Oh, one more thing about DART I'm excited about, completely removed from planetary defense. Mat, you can correct me on this. Is this the first purposeful, how would you frame this, cosmic engineering process, we're modifying the orbits, or orbital engineering process, that we're purposely changing the orbit of a celestial body for a specific purpose by humanity?

Mat Kaplan: The keywords there being purposefully, for a specific purpose, because, of course, every time a rocket takes off from Earth, you modify Earth's orbit by some amount.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. That's true, or if you do a fly-by of Jupiter, right, you're grabbing a little bit of Jupiter's energy, but I-

Mat Kaplan: And I suppose Deep Impact also made some maybe more significant change when it struck all those years ago. But, yes, I'm sure that's the case, that this is humanity reaching out-

Casey Dreier: Smashing something.

Mat Kaplan: ... sort of shaking its fist-

Brendan Curry: Celestial re-engineering.

Mat Kaplan: ... at the universe. Yeah, celestial engineering. I like that.

Casey Dreier: Celestial engineering. Thank you. That's what I was-

Mat Kaplan: That'll be a whole new discipline, CE, celestial engineering. Casey, it's your turn. What's your next topic?

Casey Dreier: Okay. Next topic that I think is legitimately very important, particularly for Brendan and I's next decade here working at The Planetary Society, sorry, Brendan, you can never leave the Society-

Mat Kaplan: Neither of you can.

Casey Dreier: ... is the decadal survey for planetary science is planned to come out March of 2022. We talked very recently about the astrophysics decadal survey, which will set, really, the next two decades of space-based telescopes. The equivalent for planetary science, where we're going to launch in our solar system, what types of missions we invest in, where we go, and what types of questions we're going to try to answer, is going to come out in a few months, and that nominally impacts the next 10 years of planetary science in the United States and, really broadly, the world because the US does so many international collaboration. It really sets the tenor and focus for a global investigation into the solar system.

Casey Dreier: And, frankly, it will continue beyond the next 10 years, as these missions take a long time to build. They go on for years. It takes them years to get where they're going. So the report that comes out in March will be really defining our future in the solar system for probably the next 20, 25 years. Of course, we contributed our input to that process as the organization. Going to be fascinating to see what comes out of it. Really, we're going to see what is the top mission recommendations, these flagship missions that they're going to come out with, because, again, NASA tends to follow that recommendation, and we're seeing the fruits of that as we speak.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, you're nodding your head.

Brendan Curry: Congress takes the decadal almost like scripture. Not to get ecclesiastical, but they take that as the gold standard. I haven't seen it happen recently, but I've seen it happen before when people that saw that their pet project didn't make it into the decade, they'll go to Congress and complain and try to get their project still funded, but Congress always points to it and says, "Hey, it came out of this. It's a pretty apolitical product. We trust the people that populate the decision-making body there." It carries a ton of water, and NASA will... In some ways, I think, it gets NASA out of the problem of having to pick which child they like the best, and so NASA can just say, "Well, the National Academy said project A, B, and C or the top three priorities. Sorry, X, Y, Z, you didn't make it. So next time, try something else." It's almost like a political relief valve for those of us who work on the Hill, and I think it helps the agency as well politically.

Casey Dreier: Great example, Brendan, of the point that you're making is the difference between Europa Clipper and the Europa Lander project, where Europa Clipper was highly ranked, basically tied as the top recommendation in the last decadal survey and had a huge political backer in John Culberson in Texas. After he lost his reelection, the mission continued anyway at a very high funding level, and it's going to happen. It's going to be launched in a few years. He really also wanted the Europa Lander, which was not in the decadal survey. While he was in office, he was able to direct money to it, but as soon as he left office, that money went away.

Casey Dreier: They were not able to continue a broad coalition of support for the Europa Lander project, I think, because it lacked the endorsement of the decadal survey. So it became a small interest group people who wanted it to happen, but they couldn't leverage that consensus process to continue that effort beyond this. So, now, they have to wait for the next decadal survey, not to rubber stamp it, but to stamp its approval on it or not. So I think, again, you really saw the benefit of the decadal survey with Europa Clipper and why we don't have a Europa Lander project now.

Mat Kaplan: Jog my memory, guys, and maybe specifically you, Casey, because I know you were one of the authors of The Planetary Society's submissions to this process. We weren't so much saying we would like to see this mission as we were saying be bold?

Casey Dreier: There was a number of things. The decadal survey process for this time around also incorporates planetary defense as a consideration, and so we focused on planetary defense as not just relevant but saying we have this opportunity with Apophis, the near-Earth asteroid that's going to be doing a close approach to Earth in 2029. There's a real opportunity to do some exciting science, and it's almost like a dry run of how quickly can you make small missions to go and investigate a near-Earth object as it comes by Earth in a seven-year timeframe. We also really promoted the search for life as a theme to integrate in planetary science and to prioritize missions and to see it through that lens.

Casey Dreier: So we didn't necessarily say one mission over another. We were encouraging this kind of ambition to say, "Let's answer the biggest questions, how do we step forward to do that," and justifying it, in a sense, because the search for life is one of those unpredictable step functions of human knowledge, right, that we have these periods of time where we make incremental progress in our understanding of the cosmos, but finding life in our solar system, which is distinct from finding it through a telescopic observation of an exoplanet, right? You find it in the solar system, it is potentially possible to... You can interrogate it in situ, right, where you find it, with all the sorts of instruments we can create on spacecraft, or you could even eventually bring it back and study it on Earth. Huge levels of increases in terms of capability to understand what we find here in the solar system versus something very far away that we can never access directly, and because of that, because we've now extended biology beyond Earth and can study it directly, you have a potential for this unpredictable step function of human knowledge.

Casey Dreier: The consequences of that generally can be profoundly positive in ways that we can't even predict because having an alternative system to study life and biology could have revolutionized an understanding of medicine, of biological sciences, of evolution, all these things that we are unable to study with a data point of one that we have here on Earth. Pursuing this... And I think there's actually real potential synergy with what astrophysics decided to do, which was their top priority, let's remind everyone, was this life-hunting super Hubble Space Telescope that will be able to do a statistically valid survey of Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone and study their atmospheres for key signatures of life. Astronomy is going for the fences and saying, "Let's try to really find life in the next 25 to 30 years."

Casey Dreier: I think there's a great way that NASA's planetary program can do a similar investment in life, looking at some of the most habitable environments, Europa, Titan, Enceladus, in the next 20 years to really make an effort to find something big. So it was a synergistic opportunity to align NASA science with perhaps the biggest question that we have as sentient beings and being able to make serious advancements on that. So I think that's what we recommended. I think there's a lot of support in the community for that, and, obviously, that's going to be one of the big things I'll be looking for.

Mat Kaplan: Stay with us are more of our look ahead at 2022 on this month's Space Policy Edition.

Sarah: There's so much going on in the world of space science and exploration, and we are here to share it with you. Hi, I'm Sarah, Digital Community Manager for The Planetary Society. Are you looking for a place to get more space? Catch the latest space exploration news, pretty planetary pictures, and Planetary Society publications on our social media channels. You can find The Planetary Society on Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. Make sure you like and subscribe, so you never miss the next exciting update from the world of planetary science.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, we come back to you for your second of the topics that we're going to address during this Space Policy Edition.

Brendan Curry: Well, thank you. A little bit closer to home, the ISS. Over the holidays, it was announced by NASA that they will plan to extend that platform up until 2030. Our European and Japanese friends seem to be pretty happy with it, although the geopolitics with the Russians could complicate it or make things even more interesting. So that's going to be a hot topic in the coming year. Also, with respect to ISS, Boeing's going to once again attempt to launch its CST-100 Starliner. That's Boeing's offering to provide commercial crew access to the Space Station. Even late next month, we're going to see the first commercial mission to the Station, human commercial mission, by a company called Axiom. I think they're targeted for February 28th. They want to eventually tack on their own private module to the Station.

Brendan Curry: By extension, with respect to ISS, over the past several months, you're seeing real stirrings in different space companies teaming up and trying to work putting together commercial LEO platforms and habitats. Wonderful as ISS is, it can't remain in orbit forever, and so if these private companies can provide private human stations in orbit, it still gives us access to LEO. It helps NASA come up with a transition plan for the eventual retirement of ISS and enable NASA to divert resources to other things out beyond low Earth orbit. I think you're going to see a lot of activity with respect to that. So for Space Station, the ISS community, now they have some certainty, and they can start making intelligent decisions on how to take next steps. The fact that, 15 years ago, there were still questions about commercial launch and its value, I think that's now stare decisis, and you're going to see people being much more relaxed about the notion of commercial/private space stations and low Earth orbit.

Mat Kaplan: I have seen such exciting concepts from a number of companies for these potential stations, inflatables, others, but a lot of them look to the ISS as a base, as a starting point, right? I mean, isn't that a good part of why we've seen now the life of the ISS extended out to 2030, because it's going to play an important role in the achievement of these other stations?

Brendan Curry: I think there's going to be mountains of lessons learned from the development, launch, assembly, and continued operations of ISS that will retire a lot of the risk that these private platforms would provide. I think you'd probably have a lot of ISS veterans start to be hired by some of these new up-starts and provide their experience. There may have been some things that on hindsight we wish we hadn't have done with ISS the way we did it, but we didn't know much better anyways at the time. There could be some lessons learned.

Casey Dreier: The key thing to look forward to in the next year is, to me, how the Russians are going to react and engage because it's not just NASA's decision to extend the life of the ISS, right? The Russians have to... They're the biggest partner. A good chunk of the station is theirs. They have to be in to 2030. We obviously have seen a degradation in relationship between the US and Russia over the last 10 years, and the question will be does that finally start to stress the relationship of the ISS? I mean, again, the ISS, symbolically, this is why it's so important, I think, is it was meant to be this special place that no matter what happened between these two nations, ISS was a point of shared value, of shared goals, of shared communication.

Casey Dreier: I was just listening to a discussion with the NASA administrator, Charlie Bolden, during the Obama years, and he talked about how during Crimea... When Russia invaded Crimea, he said there was a bubble drawn around the ISS by both Putin and Obama, that it was isolated from, and even though there were sanctions made on Russia by the US, they always exempted the needs of the Space Station from that. I think that's, in a sense, the power of the ISS and the original dream, the whole post-Cold War dream. I really am going to be interested to see the Russian reaction. Are they going to be coming in in good faith to extend it? Are they going to play shy about it and talk about maybe not doing it? It is also their primary human space flight project, too. They don't have a lot of options. Seeing whether this relationship, if the ISS is still able to continue being this idealistic representation of shared goals and cooperation in space, is what I will be really focusing on in '22.

Mat Kaplan: Just a point of clarification. You said Russia, biggest partner in the Station. You meant biggest partner to the United States because the US is still... Isn't it by far the biggest investor?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, yeah, yeah. To the Station. Yep.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, I want to address also the fact that China plans to complete its space station. They're going to fly up to what's already there, a couple of more modules, and apparently they plan to make it its own international space station. They've had several other nations say that they are in and want a piece of this.

Brendan Curry: Yeah, that's definitely something to be considered. I mean, over the past at least two or three years, you see joint statements between the Russians and the Chinese talking about going to the moon together and things like that. The relationship between the Russians and the Chinese historically have not exactly been hunky-dory. It'll be interesting to see how that plays out. I think one of the things we've tried to do with our experience with the Russians is treat them as equal. Will the Chinese view them as a junior partner where they say, "Well, we built this station, if you guys want to come and hang out at our playground, we'll let you?"

Brendan Curry: They're right next to each other. They've got a lot more geopolitical tensions between them. You got India right there. There's a lot at play here. I mean, its space station is a very small part in terms of international engagement with a variety of countries. We tried to entice the British back in the '80s to join Space Station. Reagan went to Thatcher and made an entree to her, and we all know how close they were together. She still turned him down. So anything could happen.

Casey Dreier: Geopolitics. Wow.

Brendan Curry: Yep.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, let's go on to your third major topic.

Casey Dreier: My third is the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program at NASA, this grand experiment. Again, I don't think enough people have really internalized how big of an experiment this is. The implications are what I'm very interested in because if it is successful, basically, again, the commercialization of payload delivery, of scientific instruments to the surface of the moon, could have and resonate with the scientific community for decades going forward, and not just at the moon but at other planets. Likewise, a failure will really test the resolve of NASA and the public and its congressional oversight overseers as to whether to continue with commercial public/private partnerships for this type of difficult deep space access.

Casey Dreier: NASA's spending about $300 million per year on the CLPS program, and that includes giving these fixed price contracts to a handful of companies that are building these commercial landing platforms. It includes building scientific instruments for NASA scientists and US scientists to attach to these platforms, again, with the idea being that if you have a standardized platform for access to the surface, you can start launching lots of... You can just tack on instruments all the time. It'll lower the cost. Then other potentially private organizations or individuals or companies can also buy these landing services from these companies. The big flip here, and I think this is, again, the implications that have resonance beyond this year, is that this is a very different way of doing science than the modern US scientific community is used to. Basically, since the post-war period, science is done by... Again, we were just talking about the decadal survey process. You start with the questions, you work backward, and then you make these highly specialized one-off missions designed specifically to answer that question. That is how it's been done for 75 years now.

Casey Dreier: This process flips that. You have a fixed platform for lending instrumentation. It is a generalized platform. It is not made specifically for your instrument. You have to adapt and work with the commercial provider to get what data you can through their limitations, which are commercial and income-based and access-based. You're siphoning off science from a platform versus having a whole platform made just for you. To a degree, I would add the SIMPLEx missions to this, these small CubeSat missions that are going to be going around the lunar environment as well. It's a much more limited approach. It lowers the cost to some degree, and it has the potential to increase access. But, again, you're also taking on a lot of risk in terms of it's very hard to land on the moon. We saw that with Beresheet, right? Landing on the moon is no easy task, and we're asking, I think, three to four private companies who've never done this before to deliver tens of millions of dollars of scientific instrumentation starting this year.

Casey Dreier: We ran this experiment to some degree with Better, Faster, Cheaper in the late 1990s, and we saw that when we had the failure of two low cost Mars missions in 1999, it turns out that they weren't low cost enough to avoid the ire of the public and congressional oversight in terms of what they perceived as wasted money. So if we see failures with CLPS, will the program be able to continue? Will it still have this promise of being extended? We saw a recent report come out from the Keck Institute of Space Science that was promoting this idea of low cost access to the Martian surface, using CLPS as a model, using this public/private partnership as a model. So will that continue if we see failures, or will we be able to push through those and see success? There's real turning point for how space science is done based on whether we see CLPS succeed this year.

Brendan Curry: I think one of the themes you've been seeing with Casey's remarks today about these kind of inflection points with different systems, different acquisition modalities, my remarks about private space stations and commercial space stations, the Pentagon's gaining comfort level with trying new ways of doing acquisition for space, the anxiety level is much more reduced, in there seems to be a lot more acceptance of trying out new things. I think that's a good thing. I think you're seeing decision-makers in government wanting to show that they're willing to take a little bit of risk, especially to Casey's point, if it's not still something that would boggle the average taxpayer's mind. If these experiments do work out, not all of them will, you'll see the Europeans try to follow suit. You'll see the Japanese, the Indians. You'll see everyone else trying to catch up with us, including the Chinese, although their acquisition systems are a lot more opaque, so...

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, I know you want to jump in, but I got a question. Are any of these CLPS participants expecting to make their first attempt in 2022? I've seen some get pushed back.

Casey Dreier: I think at least two, I think three nominally, at this point, are trying to go this year. Yeah. They could continue to fall behind. They've already been pushed back. Just to Brendan's point, though, I think experimentation is all well and good until you fail, and I think in commercial space fight, we've seen a lot of success. SpaceX is almost this sui generis outlier of success that has set expectations extremely high. They've succeeded in basically everything they've promised to do, and so will that spread out to other companies that aren't SpaceX, and at what point does too much failure become unsustainable if we hit failure? So I think we're in this easy point now where everything's been in development and we're coasting off and, I think, the glow of past commercial success, particularly for cargo and crew, but we haven't hit the rough patch yet.

Casey Dreier: This is, again, why I'm going to be watching CLPS very closely this year, to see if they deliver, and eventually they have to deliver. I imagine when budgets start to shrink again, which they inevitably always... You go through these periods of growth and retraction. Will they persist, given that hard choices, if we have to make them in the future? Because, right now, again, NASA's entire lunar program within planetary science is about 450 million a year. It has grown substantially, and that's not all CLPS. 300 million of that is, but that's a big program. 300 million was roughly the cost of the entire DART mission that we talked about earlier, and they're spending that per year on CLPS. So there's a substantial investment being made into this effort.

Mat Kaplan: Exciting times. Brendan, let's turn to you for your third and final of these major topics.

Brendan Curry: Well, it's not as glorious and glamorous as everything else we've been talking about, but I feel duty-bound to give a crystal ball for Washington real quick. With respect to legislation, there's going to be some sort of attempt to get a NASA authorization bill. Just for our new listeners, there's authorization bills, which provide policy for different departments and agencies in the executive branch from the Congress, and then there are appropriations bills that provide the funding for those executive branch department agencies. The Senate was able to get one out last year.

Brendan Curry: It was attached to this... I think, towards the end, it was 700-something pages long, called the United States Innovation and Competitiveness Act. I think it got out late spring, early summer, was kicked over to the House, and they have not taken any action on it in the House yet, but they may make another run at that. With respect, we're now a few months into the fiscal year 2022. We're still waiting to see how that's going to go. Right now, presently, we're we're on what's called a continuing resolution, a CR, which is funding the entire federal government at the prior year's fiscal level. From what I'm hearing right now, there will be an earnest attempt to try to do a real fiscal year '22 bill, which would be good because that'll enable news starts for NASA and projects and programs that need to be increased a little bit. It enables that as well.

Brendan Curry: The other thing to look forward to in the next few months will be when the president sends his annual budget submission to Congress. It could come out sometime in February. I've heard it may be late in March. So stay tuned to that. There's other legislative considerations. There's going to be some talk about trying to resurrect the Build Back Better. There's going to be talk about some voting reform legislation, and a number of President Biden's nominations across the board still need to be considered by the Senate. So those other considerations that I just mentioned could crowd out things that we care about with respect to NASA.

Brendan Curry: Then, on the political front, we're now in a midterm election year. There's a number of things going on right now. The Republicans feel pretty good about taking back the Congress or, at very least, the House. We'll see how that plays out. As the year proceeds, I think there's going to be a flurry of congressional activity up until around Memorial Day. Things will start grinding down. Then by the 4th of July, things will really start slowing down. Don't expect any congressional activity after Labor Day because they're going to be off to the elections and campaigning.

Casey Dreier: Literally off to the races.

Brendan Curry: Literally off to the races, yeah. Then, last month, there was the first meeting of the Space Council, chaired by Vice President Harris. We in the DC space community were very happy to see that happen. In her remarks, she talked about the three areas of focus being STEM education, addressing climate change with utilization of space, assets and space technology, and establishing rules and norms. She, for example, highlighted the November Russian ASAT test. Then some of you may remember that in the previous administration's Space Council, there was something called a User Advisory Group, which was composed mainly of individuals from industry. The Space Council's looking about how they rejigger that, maybe even give it a different game, and so they have not announced who's going to populate that UAG or whatever they re-designate it as. So that's the quick and dirty from Washington.

Mat Kaplan: I'm curious about what The Planetary Society's priorities will be. I mean, I'm sure a lot of them will be continuing priorities. What are we going to be focusing on most in this election year?

Casey Dreier: There's a lot of good stuff, and the legislation that Brendan mentioned, they're very generally good, particularly for our priorities. We're in a very good spot in terms of particularly the finishing 2022 appropriations in order to get that new start for the new Surveyor space telescope, our asteroid-hunting telescope that we very much wanted to see. The big question is for the NASA authorization, is that mandates a second selection for the human landing system, something that Blue Origin has been pushing for very strongly. Will you see a commensurate increase in resources for that? That's probably the biggest legislative deal in that piece, right?

Casey Dreier: But everything else is actually pretty adherent or aligned, which is pretty amazing, really, when you think about it. There's broad buy-in to Artemis, broad buy-in to NASA science efforts. Really, the only tension point is the human landing system process, and that goes from whether you should have two commercial providers to a NASA-owned government system that you see somewhat represented in the House. So resolving that will probably be the big thing for the year. The Planetary Society is much more supportive of the commercial partnership process for the human landing system. We'll be talking about that. We'll be focusing on really continuing these investments in NASA science, continuing these experiments in commercial space flight to try these new things, to do science in new and creative ways, and to do human space flight in new and creative ways.

Casey Dreier: Fundamentally, seeing space flight as a core broad solution tool set for the domestic needs of the United States and for domestic needs of other nations, right? NASA is not a hungry baby bird in the nest asking for resources. NASA is a powerful set of opportunities to invest in to address needs of the nation and other nations in terms of workforce development, STEM inspiration, climate change, and overall engagement of the public for optimism, for a future that is bright and exciting and accessible if we choose to pursue it.

Mat Kaplan: Brendan, do you concur? Are these relatively good times for planetary science? And I'll add to that my favorite planet, good times for Earth science done from space.

Brendan Curry: Yeah. As I've said on this show before, I feel like a large part of my career was sweating bullets about a lot of these programs. It's, I don't want to say, too good to be true, but a lot of the things that we've been working on or I've been caring about are coming to fruition. A lot of the things like humans to Mars or planetary defense that used to get a giggle factor are now taken very seriously. We just got to keep on keeping on.

Mat Kaplan: Guys, I am so happy with this conversation that I think we should go into a few moments of bonus time. Are there any other topics from that long list that we've mentioned that you would want to at least mention or address very briefly?

Brendan Curry: On the human space flight side, there's still going to be some discussion about the fate of Gateway, the Psyche launch. Juno is going to be doing some extensive study of Europa. On the international side, expect some more Artemis partners to be signed on. ESA's Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer, JUICE, is going up. The Russians are going to try to send something to the Lunar South Pole. ISRO, the Indians, are going to start trying to do their first round of tests with their Gaganyaan program. They'll be crude, but they want to do a first crude mission in 2023.

Casey Dreier: The one thing that I'm thinking about in terms of what I'll be paying attention to more broadly, which goes a little bit beyond the society's primary areas of focus, is the overall market and favorability towards investments in commercial space flight companies. We've seen a very friendly market in terms that there's been low interest rates driving lots of cheap money or driving investments into potential high payoff situations, people who are making money from other investments dumping that into commercial space flight activities. How much of our current path of commercial space flight and how many of these companies rely on this current set of market conditions? If the market goes south, if interest rates go up, if investments start to dry up, are they resilient enough to endure a downturn?

Casey Dreier: You go back 150 years to when there was, quote-unquote, private space exploration in the guise of private investments of big telescopes, ground-based telescopes, in the late 19th century, early 20th century. That was also a period of high economic inequality, big concentration of wealth in individuals who are then able to use that wealth to, in a sense, launder their name through the process of science to establish these big, long-term investments in science, which ended up being great for science, right? It's great that we have the Keck space telescope and others. But it required that set of economic conditions that did not persist through the Great Depression.

Casey Dreier: Not saying that we'll have a Great Depression, but just, more broadly, I think there is a certain amount of market dependency on easy access to investments, lots of money sloshing around looking for exciting things to invest, that if that goes away, it may fundamentally change the ambitions or number of options that we have for commercial space because it's such a nascent market still. I'll be paying attention to that. I hope they continue to do great because I think it's really important stuff that's happening, but it's something that there may be a bit of an Achilles heel there.

Brendan Curry: A year ago, there was this financing mechanism that was really hot called SPACs.

Mat Kaplan: You took the word out of my mouth, SPAC, special purpose acquisition company.

Brendan Curry: Yeah, that everyone was jumping on trying to... It was easy money, wasn't getting a lot of scrutiny from the SEC. In the past year, there's been a lot of folks that are looking at that mechanism noticing that regulators are starting to pay attention, and there seems to be slowly a movement back towards doing traditional IPOs.

Casey Dreier: Well, and, remember, the reason people did SPACs was that they didn't have to disclose future revenue projections. There's all sorts of less disclosure that you needed to do compared to an IPO. That, I think, kind of maybe tells you something about the confidence that people are working with here or how much of a risk we're taking. We're seeing that start to shift already. I think we saw with Virgin Orbit recently that their SPAC was not quite as successful as they hoped for. They made half as much money as they anticipated.

Mat Kaplan: Okay. Just three more words, guys, that I don't expect you to respond to. Cryptocurrencies in space.

Casey Dreier: Sure. Why not?

Mat Kaplan: I think I'd go see that movie.

Casey Dreier: You got to line that Dogecoin on the moon, I think, and then we'll...

Mat Kaplan: Gentlemen, you have reminded me yet again of why I feel so fortunate to be, one, part of this organization that employs the two of you to do the work that you do and to be able to share these conversations with you, particularly here on the Space Policy Edition of Planetary Radio. Brendan Curry, Casey Dreier, thank you so much for contributing this deep look ahead at 2022. We'll have to get back together and see if it actually ends up with the priorities that you guys have identified. I will remind the rest of you that planetary.org/join is where you can back this great work that is underway by the Society, by Casey and Brendan. We hope that you will become a member like the rest of us.

Brendan Curry: It was great to be here, guys.

Casey Dreier: Oh, as always. And just, if nothing else, it's going to be an exciting year in space, and not always every year can you say that. So let's really savor all of this uncertainty and excitement and potential impossibility because there's so much happening that I'm so excited to see.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, just one more time, where can people learn more about Day of Action?

Casey Dreier: Planetary.org/dayofaction. Check it out. Also, if you can't commit to a full day of meeting your members of Congress, there are ways to register for free to just do supporting actions on that same day online to help your fellow members make the biggest impact they can.

Mat Kaplan: And that would go, I assume, also for the roughly a third or so of people listening to this show outside the US.

Casey Dreier: Yes. You can pledge to take action, and if you're a member outside the US, we will give you specific ways to help your fellow members here in the United States as well.

Mat Kaplan: That's Casey Dreier, Chief Advocate and Senior Space Policy Advisor to The Planetary Society. He has been joined once again by Brendan Curry, Chief of Washington Operations for the Society. I'm Mat Kaplan, the host of Planetary Radio. I hope you will join us again for the weekly show. We've got a great show. Looking forward to Artemis, the humans to the moon program. That's this week's program, our January 5th show. It's great fun. I hope you will join me every week there, and join us again on the first Friday in February for the next Space Policy Edition. Thanks very much.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth