Planetary Radio • May 07, 2021

Space Policy Edition: How Starship at the Moon Brings NASA Closer to Mars

On This Episode

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

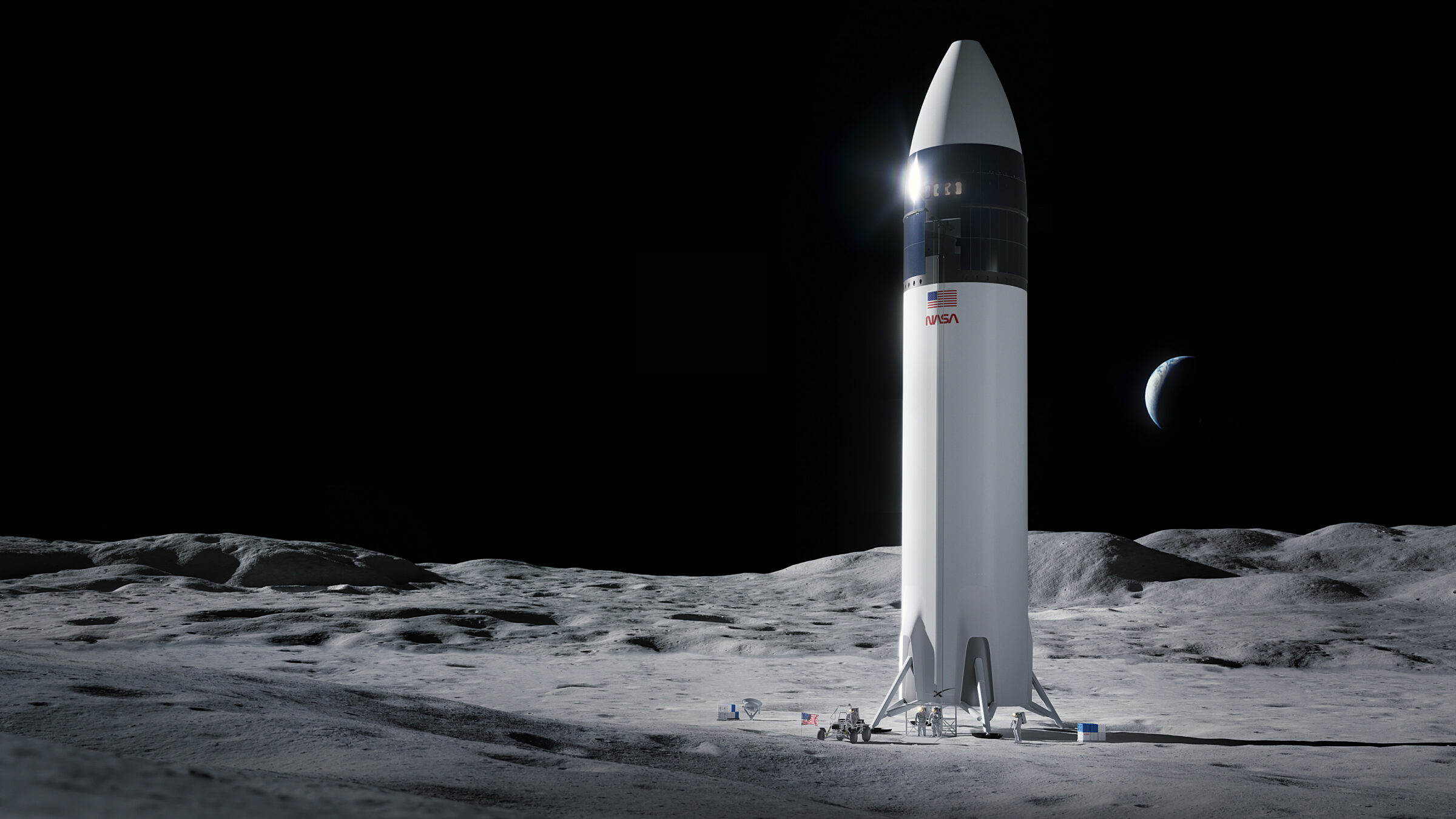

In a surprise move, NASA chose SpaceX's Starship as the sole winner of its 3 billion-dollar human lunar lander development contract. Within days, Blue Origin and Dynetics filed official protests, forcing NASA to delay the award. Casey and Mat discuss how this selection, if it stands, is a smart move for a space agency that is serious about a true "Moon-to-Mars" program. Should we stop thinking about SpaceX as a scrappy startup and instead treat it as the world's leading aerospace company?

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Welcome back everybody. This is the May, 2021 Space Policy Edition of Planetary Radio. It's great to have you all on board again. I'm Mat Kaplan, the host of Planetary Radio, weekly host that is and the cohost with Casey Dreier of this monthly installment, which is now how many years old, Casey?

Casey Dreier: Is it five?

Mat Kaplan: I think it's five. I think it's five years.

Casey Dreier: Oh wow.

Mat Kaplan: So congratulations, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Our little show is growing up.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, and I don't know if you heard, we just celebrated the 1000th episode of Planetary Radio a couple of days ago and that includes the 61 Space Policy Editions that I think we've done so far because there was an extra one in there someplace, a special one when I think there was a budget approval. So you're a part of it.

Casey Dreier: Well, man, I'm honored to help you get to 1,000. That's truly astonishing. Yeah, congratulations on making it that many. That's a... I mean, I know somewhat about how much work goes into every single episode that you do here. And that's a lot of hours you've put into those thousand shows. So congratulations.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. It's a lot of hours. No one is more surprised than me. But all you have to do is keep doing it. And eventually, the numbers tick over to 1,000. I neglected to say that for the few of you who don't realize it, Casey of course is the Senior Space Policy Advisor and Chief Advocate for The Planetary Society. You must be looking forward to being able to get out and about a little bit again. You had that great virtual day of action, but are you looking forward to getting back to DC in-person?

Casey Dreier: Oh yeah, of course. DC is always just a fun place to visit. And of course, good friends there and great to meet people and make sure that everyone I'm talking to on the computer is not just some advanced AI that is passing the Turing test and fooling me the entire time. So I have to prove that they exist in real life. But more importantly frankly, I just want to see a rocket launch. I missed the launch of Perseverance. I love politics. I love space politics, I love space policy. But man, it really helps to have that visceral reminder of watching a launch to say, this is what we're working toward.

Mat Kaplan: And how.

Casey Dreier: Is what's sitting at the top of that rocket and to feel that thing lift off. I'm eager to get out and do that again. So happily vaccinated. I've hit the two weeks. And Mat, I know you are as well.

Mat Kaplan: I am.

Casey Dreier: And I'm looking forward to the rest of the world opening up and dealing with that. I think the United States. And then of course, throughout the rest of the world as different countries are managing different variants and waves themselves. So hopefully we can get those out as fast as possible.

Mat Kaplan: Congratulations on full vaccination and the full two weeks following for full effectiveness. It's a good feeling, isn't it?

Casey Dreier: I went to a restaurant and I ordered something and it was given to me, served at the proper temperature with the proper texture and not in a box, paper box. It was a revelation. It was quite the experience.

Mat Kaplan: Well, we ate outside, but we did do it, the same thing. I had a nice outdoor table and it was just a lovely experience. Not quite up to watching a rocket launch, but not bad either.

Casey Dreier: It depends how good the food is.

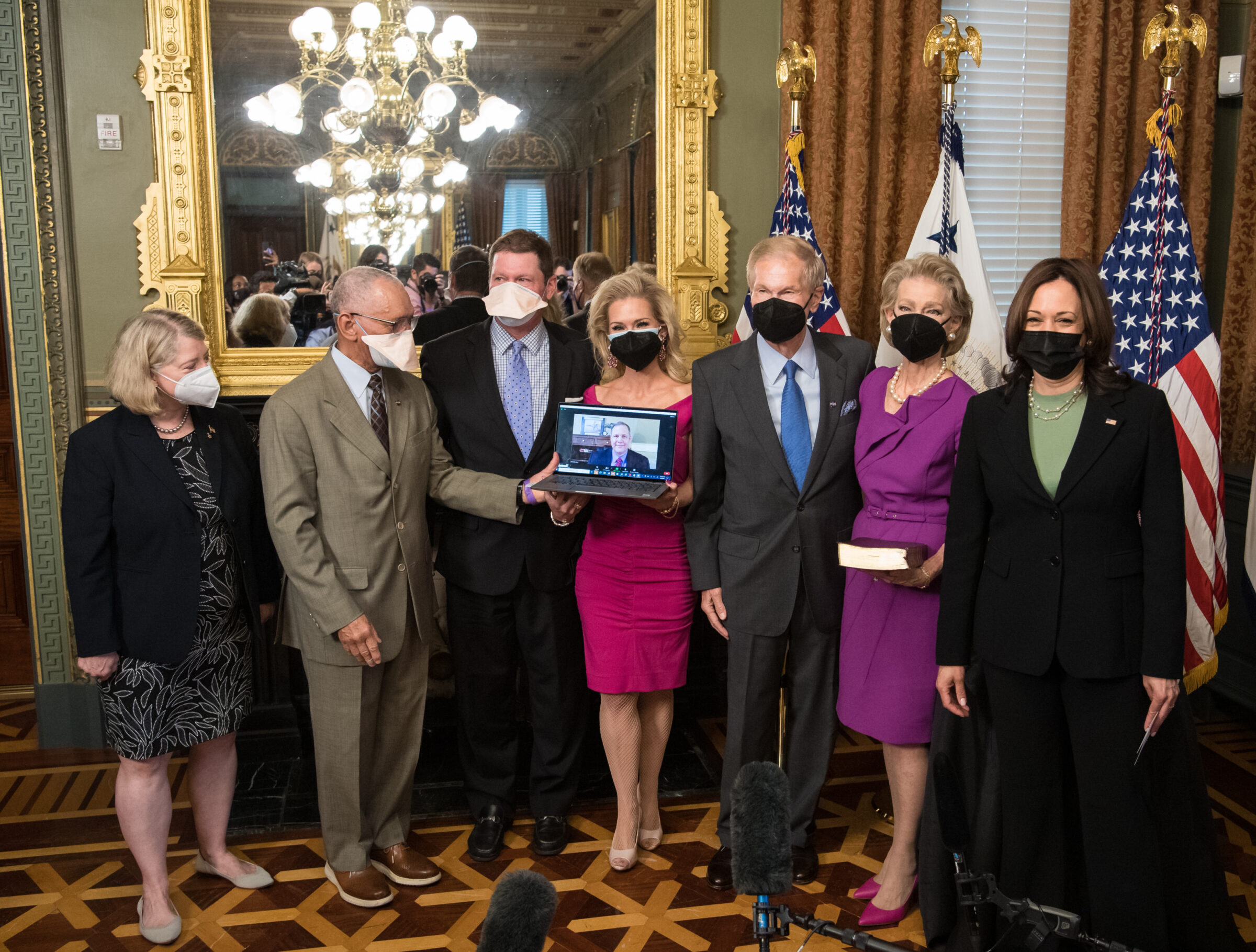

Mat Kaplan: I did note that while they all had mass on, the swearing in of the new NASA administrator happened in-person with family members with, well, at least one past NASA administrator there in-person and another being held by that NASA administrator on a small laptop. We're talking about Senator, now NASA Administrator, Bill Nelson.

Casey Dreier: That's right. It was like a Russian dolls nesting of NASA administrators-

Mat Kaplan: Yes.

Casey Dreier: ... in that scene. But yes, NASA has a new administrator, which is relatively fast within months of the new Biden administration coming in. Recall under the Trump administration that we didn't have a NASA administrator nominated I believe until the end of 2017. And it was 2018 before they came into office. And so that, and we also had really nice news that Kamala Harris will continue to, now the vice president will continue to chair the National Space Council, which was not a guaranteed thing and commitment to, again, continuing the National Space Council and seeing people staff up at the White House for more space policy hires way more space policy and space activities happening under this administration. Then their campaign would have suggested, which is a very pleasant surprise to see and very happy to see both of those things moving forward and congratulations to Administrator Nelson. And of course, The Planetary Society looks forward to working with every NASA administrator to make sure we prioritize space science and exploration.

Mat Kaplan: Equal time for Charlie Bolden, who was the former administrator holding that laptop with a beaming Jim Bridenstine on it. We actually have a little extra, but I think it's worth listening to just because of the nature of what they have to say, both Administrator Nelson and Vice President Kamala Harris. This is immediately after the actual swearing in. Let's play that clip now.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson: I want to say that it's a new day in space, but we wanted not only my family to be here, but representing the former administrator, Charlie Bolden, General Bolden, eight years under Obama, the former administrator, Jim Bridenstine, four years under Trump to show the continuity and the bipartisanship with which you run the Nation Space Program, particularly NASA. And then I want you all also to meet my deputy, yet to be confirmed, but surely to be confirmed, Pam Melroy, an astronaut commander, one of only two women, former test pilot for the Air Force, former DARPA. And this is going to be the team that will be leading NASA. So thank you, Madam Vice President.

Vice President Kamala Harris: Congratulations, Mr. Administrator and for all of the work you have done and all that you have dedicated to our country. This is going to be a good time for you to do all that you have done and bring that intelligence and that experience to this position. So thank you.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson: Thank you.

Vice President Kamala Harris: Thank you to the whole family.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson: Thank you, Ma'am.

Vice President Kamala Harris: And to the past administrators, thank you for your dedication in your work. Couldn't agree more that this has to be about our nation and what is best for our nation. I'm unencumbered bipartisan politics, but based on what we know is the right thing to do and the potential for all that we have. So thank you all.

Mat Kaplan: So there you have it. Senator, now NASA Administrator, Bill Nelson and the Vice President of United States, Kamala Harris on upbeat sound to that as well. And Casey, I bet you were, yeah, whether you were surprised, but I bet you were pleased to hear the vice president of talking about the bipartisan nature of space.

Casey Dreier: Always happy to hear NASA put in that context. And really I would say nonpartisan nature of it, of space exploration. I think NASA, again, as we pitched to the Biden administration, it can be used as a tool of engagement and relationship building to develop and pursue shared goals in areas of politics that are not so infused with partisanship. Just maybe, maybe that experience of working together can forge stronger relationships of trust between people of different parties who can then use that to continue to work for the nation altogether. But again, always really happy to hear it and that people understand that.

Casey Dreier: And also you think about again, this is not normal. You don't swear in the new transportation secretary and discuss that kind of transportation as something that brings everyone together, even though it kind of literally does. It's not really pitched that way. And so NASA, you can see again, how NASA occupies this really kind of unique place in the federal government, where it is one of those activities that because it's not necessary, the fact that we continually choose to pursue it says something about its inherent value.

Casey Dreier: Even if that value is hard to quantify, we can expand that out to not just cooperation between people of different parties, but of course co-operations between nations and space as this opportunity to bring people together on these grand projects of peaceful exploration. Always music to my ears. Happy to hear the vice president highlight that and really hoping to see that used and pursued as we go forward here in the next few months. Mat, I believe since we last spoke, there is so much space news that has happened seawise that we will see I think this really being put to the test and a lot of issues starting to go forward to really address.

Mat Kaplan: And we're going to talk about some of those developments. One in particular that you wrote about back on April 20th having to do with SpaceX and some of its competition. But let me sneak in, you didn't think we forgot, did you, a little promo here. All this hopeful stuff, all this optimism that flows out of space exploration, that's a large part of what we're all about at The Planetary Society. It's why we have Casey doing the work that he does, Brandon Curry there in Washington, DC representing us and promoting these very goals and initiatives.

Mat Kaplan: We hope that you will want to become part of it if you're not already. If you're already a member, well, thank you. Thank you very much because you make it all possible. And if you're not, take a look at planetary.org/join and please consider becoming part of this grand nonpartisan effort that Casey was just making reference to. Casey, I know you want to talk about it. You and our colleague, Editorial Director, Jason Davis did write about it on April 20th. The article was titled, why NASA picked SpaceX to land humans on the moon, subtitle, and how the decision will help humans land on Mars. It's a pretty big development and not one that has gone without controversy.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, I'd go as far say it could be the most consequential decision by NASA when it comes to returning to the moon. You've probably heard, if you're listening to this show, you've probably heard this news that SpaceX is... Starship was chosen as the lunar lander. That the other companies, Blue Origin and its national team and Dynetics have both filed official protests to the Government Accountability Office protesting the award by NASA to SpaceX. And you've probably heard that NASA has temporarily suspended activity on this project or at least the flow of money for this contract to SpaceX as a consequence of that.

Casey Dreier: So this is big news. It really, of course, I think made it into headlines and of course, the space community has been already talking about it. We'll talk about that, but I also really want to think about kind of the broader implications of the decision and also the kind of the policy and politics that follow from this decision as well. So this won't be so much a discussion of the technical merits or exactly how things work because obviously you're listening to the Space Policy Edition. We have to stay true to form here. I think the entire thing can also predicate this to, Matt where you know from reader or listener comments that people have critiqued us and me over time for not being a big enough SpaceX fan, for being too kind to our large government supplied contracts of the Space Launch System and Ryan.

Casey Dreier: And I stand by all that obviously. But I think I've been in an interesting position of being a very bullish supporter of this original decision to award this contract to SpaceX. And there's a fundamental reason why that I explain in this article with Jason. This isn't just about going back to the moon. Going to the moon is part of what NASA is claiming as a moon to Mars program. That Artemis is just a further step. It's so easy for that to be rhetoric. It's so easy for that to just be words on a page or a PowerPoint presentation that says, we're going to go to the moon and then Mars. Well, how do you do the Mars part? Well, we'll figure out after we get to the moon.

Casey Dreier: Obviously, we all know space is hard, but there is an institutional and I think behavioral tendency to optimize for the problems that are the most immediate and to solve your immediate needs at the expense of the future. And that was always my worry about a moon to Mars program, where you could find yourself if you optimize to solve for getting humans on the moon as fast as possible that you find yourself in a sense in a lunar cul-de-sac instead of on a road to Mars. And that you've created these wonderful pieces of hardware and operations and supply chains and systems that can get you to the moon, but then keep you at the moon. And it's hard to break out of those over time.

Casey Dreier: And we can look to any number of large, particularly human spaceflight programs like the Space Shuttle or the International Space Station. They have their role obviously in developing a long-term presence in space and pushing humans beyond low Earth orbit, but can also act as a yoke around the neck of the program with an ongoing cost operationally both in time and in money that prevent investments from being made into the future programs. And this is why I'm excited about the SpaceX selection and that what NASA chose of the three contenders between the Blue Origins national team and Dynetics was the most Mars forward general solution-

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: ... for returning to the moon.

Mat Kaplan: Certainly that's true. All you have to do is look at the corporate mission of SpaceX.

Casey Dreier: Right.

Mat Kaplan: It is focused on the Red Planet and Elon Musk of course has made no secret about that. That beautiful rendering of Starship sitting next to a city on Mars. It's not just hardware. We've got a company that really is focused on the Red Planet.

Casey Dreier: That's exactly right, man. And again, this is what is changing and has changed. And really what I think defines again, no one likes the term new space anymore or a lot of people never did. But in lieu of a better term for this, these new era of private space companies that have ambitions beyond that of serving government contract needs. Boeing will happily make a lunar lander or a large rocket for a mission to Venus, whatever you want it to do, Boeing will make it for you. Boeing is not going to be going beyond on its own... Boeing would not launch the SLS without NASA's contract. It's not some preexisting goal of that company to send people into space in this large heavy lift rocket.

Casey Dreier: This is the really interesting development I think. And this is what is profoundly changing the nature of space exploration in this century. This is what I think we're going to see as the demarcation of the 21st century style of spaceflight versus the 20th century style of spaceflight is that you have organizations with independent goals that exist outside of national space agencies. Whether or not those can happen, we're running that test. We don't know if SpaceX can do it, but we do know that one of the wealthiest people in the world is putting their entire, almost their entire resources and focus onto the goal of sending humans to Mars for long-term. We do know that the wealthiest person in the world wants to send humans into space for the long-term with Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: That these endeavors will happen whether or not NASA's domestic political boundaries allow it to support that. And so in this case, what's so interesting and this is what we wrote about where NASA's immediate political focus and the coalition it has built for itself politically to allow itself to return to the moon is an interesting mix of existing old school aerospace contracts, SLS and Orion, it's a mix of these new companies, not just SpaceX, but with the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, where you have Astrobotic and all these other Lunar Payload Delivery companies. And then-

Mat Kaplan: Also known as CLPS.

Casey Dreier: ... Yep, and then also of course, you have the supply services for the Gateway. You have international partners coming in at the Gateway project. So they've assembled this kind of motley mix of programs in a somewhat Frankenstein like political coalition building process, which I think will prove to be enduring if can get off the ground. This is how you build coalitions, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: In the process of doing that, they now have the ability to select partners who share those values, but also can carry them into this further step that they may not be allowed to focus on yet. So NASA does not have funding or political ability to invest directly in a human rated Mars landing system. It's just not something they're able to do. But what they can do is because they're returning to the moon, they can invest in a company that will get them to the moon, but it's also independently investing in that Martian landing capability, right?

Mat Kaplan: Mm-hmm (affirmative)

Casey Dreier: So because if you strategically choose your partners to meet your immediate need and set you up for your next step, that is a much smarter move than just finding a partner who will meet your immediate need and nothing else.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: So that's what excites me about this decision.

Mat Kaplan: We can hope that it will move forward in one forum or another because of course, as you pointed out right now, protests have been filed by both Blue Origin and Dynetics, which it should be pointed out have not built vehicles like this ever. In Blue Origins case, they've been around for 20 years now. They have one rocket, the New Shepard, which has been pretty successful. But their giant leap to a heavy lift vehicle, the New Glenn seems to have been somewhat stymied. And this is not really the direction that you were going in, but I'm just wondering there has been some coverage recently, including by your former guest on this show, Eric Berger at Ars Technica who has written about what's going on with Blue Origin. And are we now going to see Jeff Bezos maybe spending more time there to try and give them a little kick?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, I do think we're seeing that. I mean, he's no longer CEO of Amazon. If you look at their history, they have lost multiple competitions now for-

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: ... government contracts, which become this bread and butter of a private space company. Even with his wealth, you'd rather not spend your own money I'm sure like anybody. But it also becomes a statement of support and buy-in from a discerning customer, the US government. Everything I just said, it was kind of interesting. That SpaceX is going to be doing this one way or another. And Jeff Bezos has said, he's doing it one way or another. So why are they fighting this contract award. On the show notes, I'll provide a link too. You can read Blue Origin's full protests that they posted. It's redacted with some numbers, but you can read the argument that they make and you almost see it.

Casey Dreier: And I frankly don't want to spend too much time on a literary review of this because I'm not a contract lawyer. And it's hard to say exactly what it is, but you can almost read this contract. It's almost like their good name they felt was solely by this contract award. They make two big arguments. One is that NASA's evaluators on their technical side were just flat out wrong. And they were incorrectly dinged on a technical side for things that NASA messed up on. That's their job. So that they were technically great. That's probably, I would imagine that's par for the course and pretty much any-

Mat Kaplan: Sure.

Casey Dreier: ... protest like this. And the other is an interesting one saying that, their argument was that NASA always said that they intended to choose two providers. By not doing that and saying that money was a limit fundamentally changed the contours of the competition in an unfair way. And they were not allowed to come back and try to appeal to that cost or selection limit.

Mat Kaplan: And didn't Dynetics make the same argument that basically NASA changed the rules in the middle of the game?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, so I mean, and that's [inaudible 00:22:02]. So again, why did they do this? Well, I mean, we can step back. There's a very basic reason. And this is not uncommon for a large government procurement contract decision to be challenged by the people who lost it. This happens all the time.

Mat Kaplan: All the time, yeah.

Casey Dreier: Because if you look at it from the losers perspective, if there's a non-zero chance you can overturn the contract and get the money, well, you might as well. They don't get charged a fee. They don't get dinged on it for challenging it. There's no cost to them in a sense for challenging it, but there could be a reward in it. And so just balancing out the incentives, you challenge it. SpaceX has challenged a plenty of contracts itself in the past. I believe we talked about one a few years ago where the launch of the Lucy spacecraft was at risk because SpaceX challenged the contract award of that launch to the United Launch Alliance-

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: ... and nearly blew the launch window of Lucy.

Mat Kaplan: It strikes me. This is kind of the aerospace industry version of Pascal's wager. You can't really lose-

Casey Dreier: And guess what? Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: ... you might as well go for. But I did read that only about 15% of these protests are ever sustained.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, procurement officers and the whole process, it's a highly structured legal process on the government side, specifically on anticipation of potential contract challenges like this, award challenges. And this is why you never see NASA employees, particularly ones who are in charge like Kathy Lueders in charge of selecting these, responsible for selecting these awards. They can never talk about it while the award is in process. You'll always hear them say, well, there's an open competition or there's an open contract competition. I can't speak about this, blah, blah, blah. That's all to protect this process.

Casey Dreier: The GAO is not full of rocket engineers. They're going to review the contracting process, the actual formal process and made sure that it followed the rules. I would be surprised given, if you read through the award selection letter again, that will link to and why they chose SpaceX, the government, I don't think is under any obligation to choose multiple providers. The arguments about money are somewhat odd, let's say because they really did not get what they asked you. The Blue Origin contract says, oh, NASA, it's ridiculous. They should only go down to one contractor because NASA requested $15 billion over the next five years for the lunar human landing system.

Casey Dreier: But of course that was the Trump administration. And I think that the implication here, if you kind of are reading between the lines of the NASA selection and what NASA was talking about when they didn't get the money. This is not just Congress not giving them the money. This is the Biden administration saying that they do not anticipate asking for that much more money either over the next four years. If the Biden administration was going to come in and say, NASA only got 25% of what it asked for in 21 for human landing system, but we're going to ask for 3 billion again. You would've seen two awards. That would have been the baseline that would have worked from.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Yeah.

Casey Dreier: So I think what this implication is is that the Biden administration itself is not going to ask at a high level of funding. There are fine with having one provider. They don't want to pay for two. Their other priorities are going to take higher precedence. And then this is a consequence of administration change. This is not what the Trump administration would have done almost shortly. I will be surprised if it gets overturned, it could be. I would be surprised. But again, I'm not a contract lawyer. And I think what you're seeing here is, in a sense, a pushback against the idea that Blue Origin wasn't technically proficient. I think a lot of that contract protest is defending its good name in a sense of what it did and also saying that the money thing should have been adjudicated more fairly. SpaceX came in with the lowest proposal by a factor of two.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: And you can read in the letter from, again, what NASA released on the contract selection saying that there was so little money left over after choosing SpaceX that the government could not in good faith negotiate with anybody for a second award because they would be saying, "Here's $15 million. Can you match it with 6 billion of your own money or something like that?" It's frustrating. And the fact that they have to suspend, again, that standard, they usually will suspend an award while it's being contested. The powerful thing and this is what I was talking about about this fundamental change that's happening around us, where NASA is aligning itself with, this is the true public private partnership, they're aligning themselves with ambitious partners. And as we're speaking, SpaceX is attempting another launch of the Starship, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: So work on the Starship will not pause while this is being adjudicated. That is kind of one of, again, the powerful things about this. And there's another point that we need to remember about this that I think a lot of people and I put myself in this to some extent and the media too and in the space community still act like SpaceX is some startup scrappy organization, but they're launching people into space. Two countries and SpaceX launch people into space now. Russia, China and SpaceX on behalf of United States.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: They're the... I'd say arguably the world's most capable aerospace company that have earned their way into a... They're proposing a wildly audacious technically challenging solution for landing humans on the moon with Starship that involves a lot of cryogenic fuel transfer, lots of launches in low Earth orbit, but they have delivered. This is not coming. We have to take in this data that has happened over the last 10 years of delivering on commercial cargo, delivering on Commercial Crew, delivering on promises of reusability. It is truly impressive what they have demonstrated their ability to do. And if we don't take that new data into consideration and revise our, in a sense, assumptions as a consequence of that, then we're not looking at the full picture. And so if you just step back and say, of the three companies, and you were kind of pointing this out earlier, man, of the three companies that pitched lunar landers to NASA, NASA chose the only one with demonstrated capability, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Yeah.

Casey Dreier: And is actually flying and actually working on the actual system already. So the one with demonstrate capability and the lowest price. So yeah, of course they would choose that one. It makes total sense. How do you protest that?

Mat Kaplan: Stay with us. Casey and I will be right back with more of this month's Space Policy Edition. Where did we come from? Are we alone in the cosmos? These are the questions that the core of our existence and the secrets of the universe are out there waiting to be discovered. But to find them, we have to go into space. We have to explore. This endeavor unites us. Space exploration truly brings out the best in us. Encouraging people from all walks of life to work together to achieve a common goal, to know the cosmos and our place within. This is why The Planetary Society exists. Our mission is to give you the power to advance space science and exploration. With your support, we sponsor innovative space technologies, inspire curious minds and advocate for our future in space. We are The Planetary Society. Join us.

Mat Kaplan: You haven't mentioned Congress, which made it pretty clear, even though they were pretty kind to NASA at least so far. The Congress clearly does not want to throw a lot more, many more billion dollars at development of a human lunar lander. So I would guess that's a factor in addition to the administration change. The second point, we're not talking about ULA here or Boeing. I would imagine that Blue Origin and Dynetics. While I'm sure they are well-represented in Washington, they don't have the kind of clout that some other competitors of SpaceX might've had dropping hints after filing a protest like this.

Casey Dreier: Two good points there to think about. So let's take the first one. Congress, you're right. Congress, there was presented with a request for $3.3 billion to fund lunar landing. They gave it 850 million. And this isn't just because of partisanship because there was a divided Congress at the time of the Trump administration. We can look at the time Republican run Senate's proposal to fund NASA in 21, responding to a request from the Republican president. They provided I think 1 billion out of the 3.3.

Casey Dreier: So they weren't falling over themselves to fund that program either. Congress has not shown much interest in funding it at a high level. Let's not completely dismiss 850 million. That's a nice chunk of change. But that's science mission level funding. I mean, that's a year peak of James Webb Space Telescope kind of funding. Not your usual amount of funding as other people pointed out. The annual cost of the space launch system and ground systems are about 3 billion a year. The other issue is more, I think interesting.

Casey Dreier: And this is to me, the more uncertain path forward is what Congress does because let's not forget this is not just Blue Origin that put this together, this is the National Team. This is Blue Origin and Lockheed Martin and Draper and Northrop Grumman. I believe Blue Origin's strategy was the political strategy where they said, we're going to assemble large enough team. So no one can say we don't have the skills because there's enough pre-existing aerospace with them. But you can not say, no one can say no because we're going to be spreading so many different jobs around because-

Mat Kaplan: Yes.

Casey Dreier: ... Northrop Grumman, Lockheed and Draper and Blue Origin, those are all four corners of the country are pretty much represented there and everywhere in between. That's a smart political coalition building move. This is why they have to be more expensive. How can you not be more expensive when you have four large companies pitching something compared to one? And Dynetics is kind of an outlier because they usually do defense department procurement, but I believe they're well-represented. They're based in Alabama. So there's a political value there as well. So I think SpaceX actually has the weakest political hand.

Mat Kaplan: Interesting.

Casey Dreier: Almost as a function, your incentives are reversed in government compared to... If you're saving money, if you are efficient and lean, you have fewer people and fewer places around the country and your political coalition is commensurately weaker. And this is why we have things like the Space Launch System being so enduring. That will continue to go because it's not efficient. That is the political price of that program. You're already seeing this pushback. You saw Eddie Bernice Johnson, the Chair of the House Science Committee, Democrat from Texas criticizing this award. And you've seen dismay from the Washington state, Senator Maria Cantwell, where Blue Origin is based.

Casey Dreier: And you're going to see I think a push from Congress to potentially mandate two providers for human landing system. And that can easily pass without any commensurate increase in funding. That happens all the time. And so the danger here I think is that SpaceX does not have a strong political hand because it's not even securing the support of other Texas members of Congress, which Eddie Bernice Johnson is. It's because they're based in a couple places, they do not have that same kind of cloud. They can sell things for a lower price. Everyone says they want something for a lower price in government, who works in government. Unless that's not being built in your district at which point, who cares?

Casey Dreier: That to me is the big risk. This is why, again, NASA took a real risk with this in a number of different ways. So the technical risks of the ambitious program and invested in and there's the political risk about essentially choosing the least spread out, embedded, classic aerospace contractor. It's going to be in a sense of almost... It could be turned into a public relations issue where they can't, I mean, they can't cancel it. Congress is not going to go and cancel this contract assuming it's held up. But again, they could mandate a second provider and that could either handicap what NASA can do or they'd better come through with money at which point you started saying, how are they going to follow that up?

Mat Kaplan: Fascinating, I had the politics backwards. This will unfold, I assume, fairly quickly. Do we have any idea what the timeline is for considering protests like this?

Casey Dreier: I'd say in general, this can last a number of months. I would imagine we'll know by the end of the year for sure. But again, we might start to see a political response forming sooner in the next few months as we see Congress begin to move forward on the budget process for fiscal year 2022 and the NASA, potential NASA authorization bill, which is not a funding bill, that's NASA policy picking up where it left off from last year's failed attempt to pass one of those. Again, it will be very interesting to see how that plays out. And I wouldn't be surprised if you see a spike in SpaceX's lobbying expenditures this year because they're going to have quite a bit of work to do to defend, in a sense, their foothold into this single contract award.

Mat Kaplan: I guess, the only group that you can count on coming out ahead in a situation like this are all those people on, what is it? K Street in Washington are sure to come out winners.

Casey Dreier: They win. Yeah, everyone wins when there's a big dispute like this. And this is what's interesting to me that it's real money. It's $3 billion. It's not nothing. But it's interesting that in the contract award we saw, SpaceX is planning to put at least that much in on its own to do this. Jeff Bezos of course could find $3 billion in his wallet accidentally or in between the couch sheets if he has to.

Mat Kaplan: Has to work if you can get it, yeah.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, it's... And this is where I think they're looking for the imprimatur of NASA on it. It's NASA buying into you gives you this credibility, it gives you a certain level of funding stability and it allows a certain amount of buy-in from a highly respected institution. And there's something else we should mention here. This whole discussion, this whole debate is about two flights. This is what this contract is buying. Let's not forget this. It's buying one uncrewed test flight to land and one, two person test flight. Just like the commercial resupply services or the Commercial Crew Program that we saw, where they had an uncrewed flight to the station, followed by a two person crew with Bob and Doug launching last year.

Casey Dreier: The actual contract will be a separate contract for Lunar Transportation Services. That's a separate contract. They emphasize this multiple times. And I think this is getting a little bit lost in the noise here where anyone can compete for that actual services contract. So if Jeff Bezos wants to continue working on his lunar lander, he can continue to do that and then compete for a lunar landing contract anyway and NASA can choose maybe than one lunar lander in that services contract. So this story, even if it gets upheld and SpaceX is the only one, the actual process of sending astronauts to the surface is still an open debate. So obviously SpaceX would be expected to win that unless they perform horribly with the development contract. But there's no reason why NASA can select more than one for the surfaces contract.

Mat Kaplan: I remember NASA officials making this exact point that it's-

Casey Dreier: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: ... that they are not freezing out Blue Origin and Dynetics from future opportunities putting people on the moon.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, we'll look at in commercial cargo, we're seeing the Dream Chaser being added to the fleet of uncrewed vehicles, servicing cargo to the space station long after the first development, COTS program ended. That is again, what is really exciting to me about this larger thing is that when we talk about the sustainability, we're talking about ongoing services, this is an ongoing open services contract for sending humans to the surface of the moon, which I need to sometimes step back and just remind myself the implications of that phrase. That is really amazing and... We're getting to a very serious point in this program where things are actually starting to happen. And this is what I've said before and I will happily say this again, that this decade is going to be the most exciting decade in space since the Apollo era.

Mat Kaplan: You want to pinch yourself?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, it's a great decade to be in. And because we're talking seriously about who's going to win a Lunar Transportation Services contract to send astronauts to the moon and back over and over and over again. Imagine that when we'll be landing on the moon, it'll be like launches to the space station where it might get a mention on the news. It will be, but unlike Apollo, that'll be kind of the point. The point will be that it's supposed to be routine and that we'll have an ongoing presence there, an open-ended presence there. One of the things that were highlighted about the advantages of getting something as ambitious as Starship is that it's so damn big that it can carry all sorts of stuff to the surface with you, bulky and weird shaped things. And you can... It's almost a lunar lander base in and of itself absolutely.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: Right.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: But when you land.

Mat Kaplan: Well, we've talked about our did, more internal volume, then the little station that will be orbiting above it.

Casey Dreier: Right. Right, but again, and people... So and people will say, so why do we need all these other things? And let's not get ahead of ourselves. They each serve a different purpose. The Gateway serves as a opportunity for international participation, which adds stability, which adds consistency and adds that broad-based global investment into this program as well. And you don't just want it all hanging on one thing. There's an interesting consequence too of this program. So one of the big critiques from the Blue Origin protest was that NASA is taking undue risk by selecting a single provider in SpaceX for the human landing system because it's a single point of failure.

Casey Dreier: And normally that's very salient problem. Or you don't want your so-called critical path to depend on one contractor because then that one contractor, if they go out of business or something happens or they could jack up the prices or whatever that a lot rides on that one contractor performing. But it's not quite the same as Commercial Crew where contractors are providing a very important enabling service. To get to the space station, to have people on the space station is what Commercial Crew provided. But because we have the space launch system, because we're building the Gateway, sending people around the moon to the moon, but not landing on it is a completely independent set of programs and hardware that do not depend on the presence or existence of Starship performing.

Casey Dreier: So you can still have people going to the moon and orbiting it with Gateway for the first time in 50 years since Apollo 17, even in the context of where Starship isn't performing. So the consequences of the single point of failure is not great, but it's not mission ending. It doesn't prevent humans from leaving low Earth orbit and going near the moon. So I think that's a subtle, but important point by selecting a single provider. It's not like the entire program hinges on Starship delivering. The landing does, which I think is pretty important part, but it's not the only way to get astronauts out into space. And so that gives NASA, I think, some breathing room and allows them to, I think, accept a higher risk posture of that single provider, which by the way, many people in Congress and observers around have always been asking for NASA to take more and more risks. And now they do and of course easier said than done.

Mat Kaplan: You made me think a moment or two ago about a quote from our friend, mentor, John Loxton, member of The Planetary Society board. He was quoted in fact just today as we speak by Jeff Foust in his first newsletter saying that all this stuff about commercial space and you're talking about regular trips, taking all kinds of cargo and humans to the moon and back, it just kind of causes for John., Space to lose some of the romance. And he said, "That's progress I suppose." Yeah, John, I'm afraid it is. But I'm with you to a degree.

Casey Dreier: Right, no one knows the names of the people who last flew across the Atlantic 1,600 times this morning, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Yeah

Casey Dreier: The way that we know Lindbergh's name-

Mat Kaplan: Exactly right. Fascinating facets to this that I had not thought about. Are there other issues going on that we should talk about? I'm thinking in particular of some of the initiatives that the Biden administration is working to put through Congress, including that big infrastructure bill. And I have heard NASA mentioned in connection with this mentioning that NASA has something like $3 billion in deferred maintenance. Is this going to be, if it passes, is this going to be a net positive or a net not positive for NASA and Space?

Casey Dreier: I mean, I think it'd be a helpful outcome. NASA has a lot more than 3 billion in deferred maintenance. I think it's in the hundreds of billions if you do the numbers and-

Mat Kaplan: Wow.

Casey Dreier: ... it was an initiative pushed by Bridenstine a few years ago actually is to try to up the maintenance accounts for NASA's facilities management. They have something like, I forget, 150 years of deferred maintenance projects that they cannot get through at the current rate. And NASA is one of the largest owners of physical property in terms of government agencies, even though it's a relatively modest sized government agency. NASA is kind of burdened by huge amounts of physical space and buildings that it kind of doesn't necessarily need, but can't close down again, because of the congressional interest in politics that prevent them from doing so.

Casey Dreier: And so trying to find ways to streamline and improve that, not to mention modernize them, make them more energy efficient and useful for the current focus of NASA rather than building Apollo spacecraft back in the 1960s is a good idea. I don't know how much of these large bills address that backlog, but any kind of bonus to NASA is ultimately going to be good for the agency because it'll allow them to modernize, not just in terms of really basic things about again, energy use and employee happiness, but also to rethink about how it's using facilities and how it can address the needs of this space agency in the 21st century. There's bigger arguments you could make that I think were kind of missed in this bill as an opportunity about NASA itself providing infrastructure as being part of infrastructure and building out space infrastructure.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: The bill does take a very expansive view of what infrastructure means. And I think NASA and Space could have easily been included in that. And I was somewhat disappointed to see that it wasn't.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, I guess, we will mostly leave it there. I will note that as we speak, there are pools forming around the world betting on where that Chinese booster is going to come down to earth, the one that put the first segment of China's space station into orbit. Are you buying a hard hat?

Casey Dreier: I think. Technically, I have a non-zero chance of being in that debris area like most people in the world I think. Yeah, I found that somewhat disappointing that they didn't have a better disposal process for that large upper stage rocket. Most countries do and have signed treaties and other agreements saying that they shall. I'll focus more on the fact that I'm excited to see their space station come together. This is a big deal for them. And I was glad to see the first step being successful. Again, low Earth orbit again, one of those areas, it's going to be getting very busy up there-

Mat Kaplan: Very clouded.

Casey Dreier: ... over the next few years. Yeah, and we're going to have two space stations. It's a more modest space station than the International Space Station. But still, it's not an easy thing to do. And it is an ambitious construction process that they have over the next few years. And I'm excited to see what that brings to the table and what types of partnerships they can bring to advanced science, in low Earth orbit and in microgravity. So and let's hope that they work on their disposal process for future launches to make sure that they happen safely and in a controlled way.

Mat Kaplan: Hopefully the bad PR from this experience will give them a little more incentive. So yeah, two space stations and thousands upon thousands of Starlink satellites up there as well in low Earth orbit to say nothing of the other constellations.

Casey Dreier: Everyone wants to make a constellation.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, it looks like... Yeah, there are people who think that space might just be a good investment nowadays. I guess, that's progress as well John Logsdon.

Casey Dreier: If we're good in bed. We're going to see, when you talk about increasing access to space, that means all sorts of people and actors can participate in, even if it changes your personal understanding of what space is. And it's one of those things that may be kind of be careful what you wish for perspective for some people.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely, we're going to keep wishing though, that's Casey and me. Casey Dreier, who is the Senior Space Policy Advisor and Chief Advocate for The Planetary Society. And I'm Mat Kaplan, the host of Planetary Radio. We're going to, and this Space Policy Edition, but we will be back in June, probably on the first Friday in the month of June, 2021. We hope that you will join us then. And of course, I hope that you will join us for the weekly Planetary Radio installments.

Mat Kaplan: The current one right now, a really fun conversation with Andy Weir, who... By the way, Casey, I talked to him at the end about how he feels about what he sees and he expressed some optimism about the fact that he sees the bipartisan or as you said, nonpartisan nature of this and the flow from one administration to another and Space coming out ahead. I think The Planetary Society can take a little bit of credit for promoting that high ideal. If you agree, you might want to visit planetary.org/join and stand behind this effort that is carried so ably primarily by, well, it's by a lot of us, but primarily by Casey Dreier and Brendan Curry in Washington, DC.

Casey Dreier: Thanks, Mat. That's a great message. And I just want to say, I'm eager to start June, our sixth year of doing the show with you still together. Honestly cannot believe it's been five years doing the show. And thank you to everyone who has been listening and making it a successful show and letting us talk about space policy in depth. I actually think ironically, our very first episode was about how I didn't care, whether it was going to the moon or Mars for humans, just choose one and go. And how much has changed in five years. I'm all talking about going to the moon.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, it's-

Casey Dreier: It's the only thing. I think, well, the very first episode, if you'll allow me just a minute to reflect on this-

Mat Kaplan: Sure.

Casey Dreier: ... was about how there was a certain kind of stagnation in the discussions of human spaceflight. I believe that we've seen this again, this transformation happening in this last few years, last 10 years, but particularly last five years where we have broken through at a certain level that the debates that we're having in policy now are all new. A lot of them are so new. Things like mega constellations being one of them where I have very mixed feelings about them. But it's certainly not a discussion that was occupying a huge part of the space community when we started the show. We're seeing a lot of things start to happen in a way that were not possible.

Casey Dreier: Partly as a consequence of years of budget cuts, partly as a consequence of new actors coming into the space arena and really starting to see the outcomes of investments being made from previous years. So it's really... We've gone I think from a period of kind of endlessly looping stagnation and particularly in human spaceflight to really, again, starting to see exciting new developments with all sorts of new interesting problems, particularly policy problems that we're going to have to grapple with. And that's, in a sense, a wonderful problem to have to move out of bed.

Mat Kaplan: Exciting times. And we're still just getting started. Thanks again, Casey. I'll see you in a month and probably, we'll be talking before we get together again for the next Space Policy Edition.

Casey Dreier: Looking forward to it, man.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth