Why is only half of Mars magnetized?

Written by

Emily Lakdawalla

October 24, 2008

I'm working my way through a horrendously high pile of magazines that I haven't had time to read, and came across an article in the September 26 issue of Science that is really cool: it neatly explains why only the southern half of Mars is strongly magnetized.

I'll need to begin with a little background. I've talked before about what's called the Martian crustal dichotomy. Stated simply, the dichotomy is: Mars' northern hemisphere is low (in elevation) and flat, while the southern hemisphere is high and rugged. That difference is easy to spot in the marvelous Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter map of Mars, one of the signal accomplishments of the Mars Global Surveyor mission:

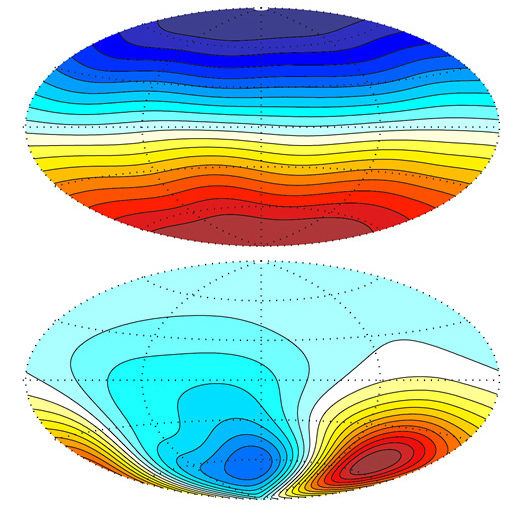

Elevation and ruggedness aren't the only things that are "dichotomous" across that sinuous north-south boundary. Geophysical evidence suggests that the elastic part of the crust is thinner in the north than it is in the south (much as Earth's oceanic crust is thinner than the continental crust). The north is covered with volcanic flows and sediments, while the south has been a place where more stuff has been exhumed than deposited. And Mars Global Surveyor produced a lesser known but still important global map, one of the strength of Mars' magnetic field, which shows that where Mars does have a magnetic field, it's mostly in the south, not the north. (Sadly, this map cuts the spherical Mars at 0 degrees rather than 180 degrees longitude, so you have to shift it by half the width of the map to match it to the MOLA map above. Use the Tharsis mountains and the Hellas basin to orient yourself.)

Mars' current magnetic field is very weak, with strengths of at most about 1500 nanotesla. Earth's, by comparison, varies up to around 65000 nanotesla, or more than 40 times stronger than Mars'. Earth's magnetic field is supported by an internal dynamo; Mars must once have had a dynamo, which would have magnetized its rocks, but then the dynamo shut down. So any rocks that formed on Mars before the dynamo shut down are magnetized; any rocks that formed after the dynamo shut down, or that were heated above their Curie point (the temperature at which their magnetic domains randomize, which differs from mineral to mineral, but which is in the ballpark of a few hundred degrees Celsius) after the dynamo shut down, are not magnetized.

It's never been easy to understand why Mars' northern hemisphere has very little in the way of a detectable magnetic field, because evidence suggests that the dichotomy is a truly ancient feature, that should have formed before the dynamo shut down. So people have had to come up with explanations for how it got demagnetized after the dichotomy formed, and the explanations have always been ad hoc. Maybe the north lost its magnetism due to alteration of its minerals in the presence of water, or maybe there were difficult-to-detect impact features after the dynamo shut down that wiped out the north's magnetism.

More recently, a suite of papers published in Nature gave credence to the idea that the crustal dichotomy formed as a result of a truly gigantic, oblique impact that blasted away a massive chunk of the crust of the northern hemisphere, and that this happened very early in Mars' history (I've written about this before). Furthermore, the papers showed that because the impact struck Mars a glancing blow, it would not have delivered enough heat to the planet to melt its whole crust. So the impact could reasonably leave Mars with a thin northern hemisphere crust and a thick southern hemisphere crust. But that still leaves geophysicists with the problem of explaining how the north didn't become magnetized, despite the fact that the dynamo was operating well after this putative giant impact.

Enter Sabine Stanley and her coauthors with their neat idea. In their Science paper, they show (using a numerical model, that is, a computer simulation) that it's possible to have a dynamo operating inside Mars that only produces a dynamo in a single hemisphere. The way they made this happen is by "impos[ing] a degree-1 variable heat flux pattern at the core-mantle boundary in a dynamo simulation." To translate: instead of assuming a spherically symmetrical Mars, they made the northern hemisphere core-mantle boundary hotter than the southern hemisphere core-mantle boundary, a reasonable initial condition to impose if you very suddenly remove a huge amount of crust atop that part of the planet with a giant impact.

Then they ran their simulation. And here's what they found. The top map shows a magnetic field simulated for a planet with no temperature difference at its core-mantle boundary; the bottom map shows their simulated Mars. Guess what? There's a strong magnetic field only in the southern hemisphere.

There's an old, old joke in physics circles about making the assumption of spherical symmetry. Here's one version:

A dairy farmer who, in a fit of desperation over the fact that his cows won't give enough milk, consults a theoretical physicist about the problem. The physicist listens to him, asks a few questions, and then says he'll take the assignment. A few weeks later, he calls up the farmer, and says "I've got the answer." They arrange for him to give a presentation of his solution to the milk shortage.

When the day for the presentation arrives, he begins his talk by saying, "First, we assume a spherical cow..."

This joke will only be funny to you if you've ever taken a physics class. But making apparently oversimplifying assumptions in mathematical models of physical phenomena usually works pretty well. The fourth coauthor on this paper, Marc Parmentier, is a theoretical geophysicist who was one of my thesis advisors at Brown. He was famous for such statements, while deriving or solving equations, as "well, pi squared is about ten, so we can cancel that..." or, even worse, "pi is about two..." -- generally, geophysicists make apparently ridiculous simplifications, because all they're really interested in is working things out in as much detail as is necessary to see whether their model produces a result that has the same sign as reality -- for instance, they'd like to see a mathematical model for Mars' crust make the north look low and the south look high, without much regard to how low or high. And if the model gives a result that's within the same order of magnitude as reality (that is, within a factor of 10), they're pretty happy with themselves. But, once in a while, someone comes along and shows that it's worth it to make your model just a little bit more complicated.

The assumption of a nonuniform temperature across the core-mantle boundary does some other neat things besides explaining why the south is magnetized but the north is not. Stanley and coauthors go on in their paper to show that since this magnetic field doesn't have the same shape as the magnetic field we're used to on Earth, studies that try to reconstruct where Mars' rotational axis may have been in the past are flawed.

An assumption made in the paleomagnetic studies is that the dynamo-generated magnetic field was axial-dipolar dominated. This assumption implies that the magnetic pole coincided with the rotation pole and is used extensively in Earth paleomagnetic studies. Our models would dictate that the Mars dynamo-generated field was not axial-dipolar dominated and hence that the magnetic poles would not coincide with the rotation poles, rendering paleopole interpretations useless.

And here's another neat trick of Stanley's model: if ancient Mars had a magnetic field only in the southern hemisphere, then there would be no protective field to prevent the solar wind from stripping away the atmosphere from the northern hemisphere. But the atmosphere flows where it will, regardless of magnetic field lines; so atmosphere would flow from south to north, and continually be lost from the north. So you could still have Mars losing its atmosphere early in its history, even while it had an active dynamo.

It's all theoretical and really a very simple model, but it explains so many mysteries about Mars, that it's a very attractive idea.

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth