A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 31, 2017

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Beats Winter, Wraps 2017, and Heads for 14th Anniversary

Sols 4926–4955

With the Martian winter on the run at Endeavour Crater, the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission cruised closer to its 14th anniversary of exploring the Red Planet in December as Opportunity deliberated a distinctive “fork in the road” deep in Perseverance Valley and wrapped another record year.

Every year Opportunity has been exploring Mars has been one of challenges and rewards and 2017 was no exception, except perhaps it was more intense than most. The veteran robot field geologist was scaling the steep, sometimes slippery-with-gravel slopes of Cape Tribulation on her way to the valley when the year began. Now, as 2017 comes to an end, the robot field geologist is deep inside Perseverance and deep into the mission’s research, the centerpiece of the team’s tenth extended mission, looking to go farther back in Martian geologic time and uncover buried scientific treasure.

It hasn’t exactly been a walk in the park. “From Spirit Mound and up to the rim and then back down Perseverance Valley, the topographic profile from 2017 is on a par with what we did with Spirit when we climbed Husband Hill back in 2005,” MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, reflected as December came to an end. “We did the most challenging, difficult driving over some of the most rugged terrain we’ve ever done with this vehicle all these years in.”

Years indeed. On January 24th, 2018, the MER team and Opportunity will complete their 14th Earth year of surface operations on the Red Planet, and then begin the 15th year of this adventure, NASA’s first overland expedition across Mars. “And the rover is still going strong and still doing great science,” said Squyres.

In fact, Opportunity is going where no robot on Mars has gone before. “Perseverance Valley is a truly enigmatic feature that is unlike anything we’ve ever seen on Mars or been able to drive to and across,” said Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. “The work we do here will be the first ground-based exploration of a preserved valley system on Mars. It’s like another new mission.”

Cutting west to east and forming a broad notch in the remnants of the crater’s western rim at Cape Byron, Perseverance stretches downhill for the length of about two American football fields (about 220 meters or around 720 feet), at a slope of about 15 to 17 degrees, all the way to the floor of the crater.

Positioned on a north-facing slope in the valley’s south wall where she could angle herself toward the Sun and soak up the winter Sun, Opportunity spent the month of December imaging at a couple of different sites about halfway down the length of the valley. Her sights and her camera lenses were primarily focused just downhill where a large trough or channel splits into two paths and creates a ‘fork in the road.’

“This is a braided channel and it divides and it comes back together,” said Squyres. “We stopped at one of the divides here for the Christmas holidays and to take a break for a while.”

The first time the MER scientists saw the orbital images of Perseverance they generally thought it had been carved by water, flowing water or melting ice or maybe a muddy debris flow. Other theories suggest the Martian winds or perhaps a dry debris flow might have chiseled the valley, and still others suggest some combination of these forces. But the water theories keep rising to the surface. The veteran Mars explorer and the MER team are here to figure it out.

Endeavour Crater dates to the Noachian Period, some 3 to 4 billion years ago when scientists believe Mars was warmer and wetter and more like Earth and Opportunity is the only rover, MER the only mission on the Red Planet, to have ever traveled this far back in geological time. Uncovering evidence of past water, of course, is exactly what NASA created and dispatched Opportunity and her twin, Spirit, to do, in the space agency’s ‘Follow the Water’ Mars exploration campaign.

Opportunity found the mission’s first ‘hard’ evidence of Noachian Mars at Cape York on Matijevic Hill in 2012–13. Discoveries there included the oldest strata found to date, the Martian ground when the impact that created Endeavour hit the surface (Matijevic Formation); remnants of ancient clay minerals, an indisputable sign that water was once here; and another never-before-uncovered ancient rock layer (Grasberg), which the MER scientists think formed after the impact.

The MER scientists are optimistic that Opportunity will journey again to that time during the Noachian Period and find the evidence needed to describe the environment here all those years ago – and how exactly the unique geological feature forever now known as Perseverance formed.

For as much progress as Opportunity made in 2017, the year was not without some significant challenges. Opportunity’s left front wheel, for one, was pulled out of steering commission in June and the rover has since steered with her rear wheels and turned like a tank. But with the ‘curses’ of exploration, there were ‘blessings.’

As steep as the slopes are, the ground beneath the rover’s wheels has been decent. “I was expecting a tougher terrain to traverse,” said Rover Planner Paolo Bellutta, the rover robotics expert who oversees the charting of Opportunity’s routes from his post at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where all of NASA’s Mars rovers were ‘born.’ “The loss of front steering capability does not help, but it is not a limitation that I feel is hindering the mission,” he said. “So far, most of our troubles are the consequence of driving on steep slopes.”

Steep slopes and rover aches and pains considered – along with the fact that this is Mars – the MER mission team and Opportunity will be entering their 168th month and 15th Earth year of roving Mars in pretty fine form. “This rover is a real trooper,” summed up Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson, of JPL. “Opportunity continues to do everything we ask and perform as we expect, and continues to amaze us with its longevity.”

When you consider that back in the beginning the team members thought they might have a year, one year outside to explore Mars with the MERs, Opportunity’s longevity is beyond astounding. The legendary success of this mission didn’t just happen though, like some kind of happy accident.

Rather, it is a kind of perfect storm of excellence, and testimony to the engineers who built Spirit and Opportunity, to every person who worked for every company that manufactured an instrument or a piece or part, to the Entry, Descent and Landing team that got them safely to the surface, to each of the scientists who lead and conduct the investigations, to the engineers who tend to the rover and craft workaround ‘miracles’ to get her where the scientists want her to go, and to the ops team at large, the dedicated people who countless times have given up weekends or holidays to care for this robot. That, all of that, is what has driven this mission to become a legend in its own time and kept Opportunity roving day in and day out.

“And it’s also an indicator of how interesting a place Mars really is,” reflected Squyres. “It’s a combination of all those. We wouldn’t keep making new discoveries if Mars didn’t keep throwing new things at us. But Mars does.”

As 2018 dawns on Earth and on Mars, optimism and gratitude continue to power the human core of the MER mission and the team’s mantra remains the same: every day on Mars is a gift.

2017 in Review

When January 2017 rang in at Endeavour Crater it was summer and Opportunity was hunkered down on a slope inside the rim at Cape Tribulation just to the north of Beacon Rock, waiting patiently for the holiday celebrations on Earth to end. The rover in November 2016 2016 had departed Spirit Mound, the first planned science stop on the MER’s tenth extended mission located deep in the rim near the crater floor, and spent the winter holidays taking a break from hiking up the steep slopes toward the rim crest.

Although the rover was designed to navigate 15-degree slopes, Opportunity was regularly hiking slopes that average around 20-degrees and more. The going was tough. The steep slopes, ragged terrain, a blinding summer Sun, and the rim wall to the west that blocked her communications conspired to slow her pace. "We're trying to get to our egress point so we can get onto the flatter terrain of the Meridiani Plains that surround the rim and make some good progress down to Cape Byron and the valley," explained then-MER Lead Flight Director and Rover Planner Mike Seibert, of JPL.

The robot field geologist had been struggling to get around a large landmark boulder the team named Beacon Rock. The initial plan had been to go around it to the east and through Willamette Valley, and then up to the crest of the rim. But the gravelly slopes and loose terrain were foreboding, so as 2017 got underway the team redirected the rover. The march uphill continued with a revised route, taking the robot to the north and west of the giant rock.

On Sol 4623 (January 24, 2017) Opportunity celebrated her 13th birthday climbing west/southwest up another slope to finally put Beacon Rock in the rear-view mirror. From there, the rover continued to push upslope, heading south and west through Cape Tribulation toward the rim.

Opportunity finally reached the crest in February. There, the robot field geologist looked around with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) ‘eyes’ and took in the views. “This is it for Cape Tribulation and so we stopped short of going over the crest to acquire a good, parting shot.” Arvidson.

From here, the rover would take an “express route” to Cape Byron and Perseverance, about a half-mile away. Driving caddy corner down the outboard side of the crater rim to the southern part of Cape Tribulation, the rover would then scoot onto the flatter Meridiani Plains terrain that lays in between the capes to fast-track her trek. Once Opportunity arrived at Cape Byron, she would climb back up, over, and into the west rim to enter Perseverance Valley.

Opportunity was about to hit the road when the scientists saw something in the rover’s images that was too intriguing to pass up. “We were about to exit the ‘door,’ but suddenly we discovered this ‘door’ is pretty exciting,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of JPL.

So, while completing the Rocheport Panorama, named for the town along the Missouri River that Lewis and Clark and crew passed through in 1804, the robot geologist conducted one last scientific campaign at the rim crest. It was on an outcrop of finely striated bedrock that looks to have been etched or carved by something. “We decided to take some detailed Pancam imaging of the area and are still debating whether the geomorphic expressions, the striations were formed by wind or ice or something else that occurred during the impact,” said MER Deputy Project Scientist Abby Fraeman, who first worked on the mission in 2004 while still a high school student and one of The Planetary Society’s Red Rover Student Astronauts.

It turned out to be more of the same breccia bedrock that Opportunity has been roving on and around since pulling up to the crater’s western rim in August 2011: rocks and outcrops formed during the impact that created the 22-kilometer (about 13.7-mile) diameter Endeavour, now known as Shoemaker Formation. The team has yet to come to a consensus on what caused the etchings.

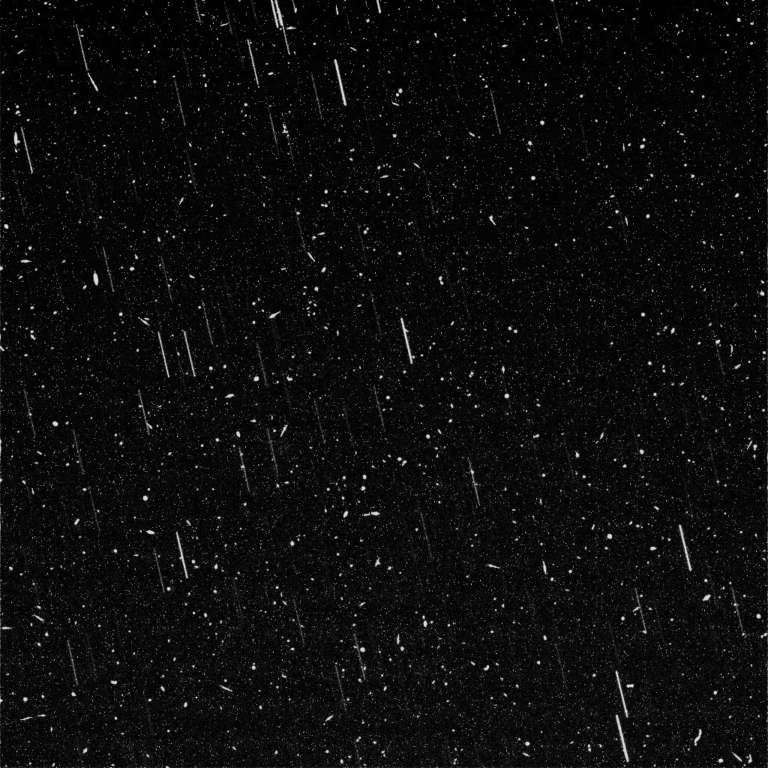

Martian summers routinely generate rover-threatening dust storms, but Opportunity was lucky enough to work under “storm free skies” throughout the month of February despite a large regional storm about 500 kilometers away. “We can actually see [the storm] in the distance in one of the Navcam panoramas,” said Callas. “This is the first time we've actually seen one of these dust storms from the ground. By month’s end, the threat has passed, but the dust that was falling out was hazing the skies over Endeavour and dampening the rover’s power. “We're keeping our eyes on it.”

As luck would have it, the storm’s winds, along with the dust, sent some gentle gusts blowing eastward to Endeavour, which conveniently cleared off some of the accumulated dust from Opportunity’s solar arrays, translating to a boost in the rover’s power. Just as the February storm began to dissipate however, another regional storm followed in its dusty wake during the first sols of March, causing concern and ensuring that dust would continue to command the skies for weeks to come.

Undaunted, Opportunity finished the final science investigations on the slopes of Cape Tribulation, then climbed up and over the crest of Endeavour to the other side of the rim, to embark on the journey south toward the valley. “Right now we are in the business of making wheel tracks and that's what we're going to be doing until we get to Perseverance Valley,” said Squyres.

The MER mission’s lucky star kept shining on Opportunity throughout the summer of 2017. Despite a prediction from NASA-JPL that 2017 may bring a planet-circling storm that would put the Red Planet in the black, the rover successfully dodged two, potentially deadly dust bullets.

Opportunity didn’t completely escape the storm’s wrath. Dust from those regional storms continued to rain steadily on Opportunity throughout March. “The dust cleaning events didn't stick,” reported MER Power Team Lead Jennifer Herman, of JPL. “We're dirtier now than we were before the storms.”

At the same time, the rolling, distance-blocking topography challenged the veteran rover, “limiting drives to around 15 to 30 meters,” said Bellutta. That’s roughly between just 50 and 100 feet. “But we are making good progress,” he said.

Indeed. Perseverance was absolutely, positively, and magnificently within reach and no one was betting against this rover.

Opportunity was scheduled to spend her first sol in April taking images of a light-toned mesa in the distance that the team christened Winnemucca. Past that, the plan for April was “Drive, drive, drive.” as Arvidson put it.

While the robot cruised outside the western rim along the flatter, plains terrain, fall was blowing in and the thick, dusty haze in the skies from the regional storms of February and March was slowly thinning. The Tau hung around 0.981. And although the rover’s dust factor had decreased to 0.597 as fallout from the storms rained down, Opportunity was producing a respectable amount of power, upwards of 400 watt-hours.

The veteran rover worked hard to pick up the pace, logging 10 drives and covering about a quarter of a mile in April, closing in on Perseverance Valley. On one drive, Opportunity sprinted for more than 130 meters (about 430 feet) in a dash the likes of which she hadn’t done probably since leaving Cape York about four years ago. It made drivers on Curiosity duty a little, well, envious.

“We’ve been making astonishing progress,” said MER Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe, of JPL. “It’s been much easier to drive on the smoother terrain.” Opportunity was now within striking distance.

Along the way, the robot managed to work in a few science investigations. One outcrop puzzled the science team. It was bedrock with a somewhat familiar composition, but one that did not neatly match any strata the mission has found so far. “Mars still surprises us,” said Arvidson. The robot found no signs of the ancient Matijevic Formation outcrops.

On May 4, 2017, the rover’s 4,720th day on Mars, Opportunity, at long last, drove into the entryway or the top of Perseverance Valley. “We’ve proved through lots of perseverance that we could make it and we have arrived,” announced Squyres. “It’s so new and so different. And it’s really, really cool.”

It was an unparalleled achievement. Imaging the views all around with her Pancam and Navcam, the rover took it in, and then set out on a walkabout. As for the view: “It’s nice and flat,” said Callas. “And all of the sudden, it just disappears over the edge.”

The fall equinox fell on the day after Opportunity pulled atop Perseverance, May 5th, the same sol that marked the start of the MER mission’s eighth Mars year, and the same sol that the mission team hit the pause button so the rover could shoot the Moon. Looking skyward with her Pancam at specifically chosen times, the robot aimed to freeze frame the fast-moving Martian moon Phobos as it transited the Sun.

“You’ve got to be taking pictures in the right place at exactly the right time,” said Mark Lemmon, an associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Texas A&M University, MER science team member, and “the brains behind the effort,” as Planetary Society President Jim Bell, the science lead on the rovers’ Pancams, defined him.

With extreme precision in the planning, Opportunity got the Moonshot. Then, the ‘bot promptly got back to checking out targets atop the valley, looking for any kind of evidence that may indicate how this distinctive valley formed as she shot images of all she could over the crest and into the valley. The images were scientific data, but they also would serve as navigation data for the rover planners to determine with certainty that the rover will be able negotiate the downward hike into Perseverance.

During the walkabout, the scientists looked through their rover’s “eyes” for telltale signs of water or wind or ice or any weird Martian thing. “In contrast to many walkabouts we have done in the past, this walkabout is all about geomorphology, the landforms,” said Squyres. That meant Opportunity would shoot “lots and lots and lots of high-resolution stereo Pancam imaging.”

Opportunity may have been dustier than last winter but true to her MER mettle, but the rover accommodated all commands and kept on truckin’ on her walkabout atop Perseverance in June. Among other geological things, Opportunity imaged a large, shallow channel or trough with “a pattern of striations running east-west outside” the crest of the rim. It might have been a drainage channel or spillway billions of years ago—or not. “We want to determine whether these are rocks that have been transported here or are in-place rocks," Arvidson said.

The scientists debated the possibility that this site was the end of a catchment, where a lake was perched against the outside of the crater rim. Could “a flood could have brought in the rocks, breached the rim, and overflowed into the crater, carving the valley down the inner side of the rim?” asked Arvidson.

If that were the real scenario, the notch in the crater rim crest leading into the valley would have been a water spillway. Weighing against that hypothesis however were the rover’s images that show the ground west of the crest slopes away, not toward the crater. The team would later determine there was most likely no lake here.

The autumn skies over Endeavour Crater remained hazy as dust from the summer storms continued to rain down, but Opportunity remained productive during her walkabout atop Perseverance, capturing image after image with her cameras visually documenting the area. Then June brought a ‘gloom’ that cast a pall on the mission team. While Opportunity making a basic arc back maneuver to turn, the steering actuator for her left front wheel stalled and she stopped, with that wheel stuck, toed-out 33 degrees.

More than 12-and-a-half years before, in April 2005, the steering actuator for Opportunity’s right front wheel jammed and stuck in a toed-in position of about 8 degrees and she has driven with it like that ever since. But 33 degrees toed out?

During the ensuing sols, Opportunity followed commands to see if the wheels had caught on anything. The rover’s images of the scene however ruled out terrain or small rocks as the cause. In the mix of all this movement though the robot scuffed up a small patch of crumbly white soils. Laramie, as the team named it, hints of past water. But there was no time to check it out up close.

The Earth-Mars solar conjunction was coming up in July and the mission’s eighth Martian winter would set in soon after. With the stuck left front wheel, there was an increased desire to get into Perseverance Valley as soon as possible and the team’s attentions turned to roving on.

Even so, Opportunity had returned some familiar Pancam spectra, and Bill Farrand, Senior Research Scientist at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado and a member of the MER science team, considered it “plausible” that the stuff could be “some kind of hydrated sulfate mineral.” The data was similar to the spectra from the “jelly donut” rock Pinnacle Island and Stuart Island that the rover found back in January 2014, farther north on the rim, just in time for her 10th anniversary.

After a series of tests and unsuccessful straightening attempts, ops engineers decided to try one more thing. Voila! On June 17th, the rover straightened her left front wheel. “It was miraculous,” said Squyres.

When the telemetry that confirmed the rover’s wheels were all straight arrived on Earth, it was a Father’s Day gift like no other for the thousands of “fathers” who helped put Opportunity and Spirit on the Red Planet and got them roving along on NASA’s first overland expedition of Mars. “The MER team experienced an exciting two weeks, but it ended with relief and joy,” said Fraeman. “Once again, the rover amazed us.”

Everyone, especially the rover handlers knew this incident could be an omen. They decided from this point onward, the veteran rover would drive in a cautionary mode. "For at least the immediate future, we don't plan to use either front wheel for steering," announced Callas. “We’ll steer with our rear wheels,” said Nelson. “And turn like a tank.”

Opportunity and the rover planners adapted quickly and the mission was soon back to work, looking for clues and finishing her imaging assignments of the rock piles along the edges of the trough or channel, as well as various rock groupings.

Bellutta, meanwhile, had worked with the drivers and the scientists to chart the first of three planned drives back toward the rim crest and into Perseverance Valley. “We’re aiming for a nice cozy spot with about 10 degrees northerly tilt,” he said.

On July 6, 2017, Opportunity’s Sol 4781, the rover drove 13.4 meters (43.96 feet) and over the rim’s edge, venturing confidently yet cautiously into Perseverance and made it look easy. After so many years, so many miles, so much effort, the mission scored a major hit. It was a stellar achievement in the annals of planetary exploration.

“Perseverance has been calling us for years,” said Squyres. “Exploring the valley is the next big science phase of the mission. This is just tremendously exciting.”

The following day, July 7th – the 14th anniversary of Opportunity’s launch from Cape Canaveral – the rover drove again, cruising right up onto the gentle north-facing knoll or slope where she could soak up the Sun while waiting out solar conjunction. Between adjusting to new driving techniques and the team’s urgent desire to get the rover parked before conjunction, the mission’s grand entrance into Perseverance turned out to be a quiet event, greeted with as many sighs of relief as cheers. But it opened the doorway to the historic science campaign inside Perseverance Valley that was about to begin.

After settling in, Opportunity took images of the valley walls, the continuations of the troughs or channels and rocks and outcrop with interesting features and the site’s morphology for as far as she could see with her cameras, peering as far down into the valley as she could. With Mars soon to move behind the Sun, the team had to prepare for the two-week communications blackout during the celestial event. “It’s kind of like we’ve just walked into Town Square on Main Street USA at Disneyland and haven’t yet gotten to Space Mountain or Tomorrow Land,” said Callas.

The Earth-Mars solar conjunction occurs every 26 months or so when the orbits of Earth and Mars place them on opposite sides of the Sun, making communications between the two planets so risky that NASA instructs all Mars missions to institute a two-to-three-week communications blackout period. “Out of caution, we don’t send any commands to the rover during this period,” said Chad Edwards, the Manager of the Mars Relay Network Office at JPL. “We don't want to take a chance that one of our spacecraft would act on a corrupted command.” So aside from brisk communication check-ins, Opportunity would be incommunicado for the latter half of July, but working on assignments the team sent up in previous weeks.

As the blackout began, the veteran explorer got to work on autopilot, as programmed. But then, the unexpected happened.

On July 23rd, JPL engineers received data that Opportunity had suddenly rebooted and as a result put herself into safe mode. “We believe the re-set of the rover's computer happened on Friday, July 21st during the morning X-band communication session, and that stopped the stored master sequence of commands,” said Nelson.

Opportunity is designed to autonomously protect herself when things go awry by switching into safe mode, a kind of auto mode that puts the rover in a safe and stable state. Opportunity was power positive, thermally stable, and would continue to honor the scheduled X-band and UHF relay communication passes through the remainder of solar conjunction. “We like to say safe mode is safe,” said Edwards. “Right now, that is the safest state the rover can be in.” Still, this was not in the plan.

The communication blackout ended August 1st. The MER ops team promptly recovered Opportunity and got her back online. The rover soon roved onward, vicariously taking the MER team, along with a global contingent of mission observers all around Earth, downhill into Perseverance and into a brand new journey on this legendary expedition of the Red Planet.

As usual during Martian winters, Opportunity maintained energy and maximized power production on her jaunts downhill by using the “lily pad” method, which enables the solar-powered rover to soak up as much of the winter sunshine as possible for power production. The team first used this strategy, during Spirit’s winter climb up Husband Hill in 2005. Essentially, the robot drives from one north-facing slope to another where she can position herself and her solar deck to the north where the Sun rises and falls in the sky during the Martian winters.

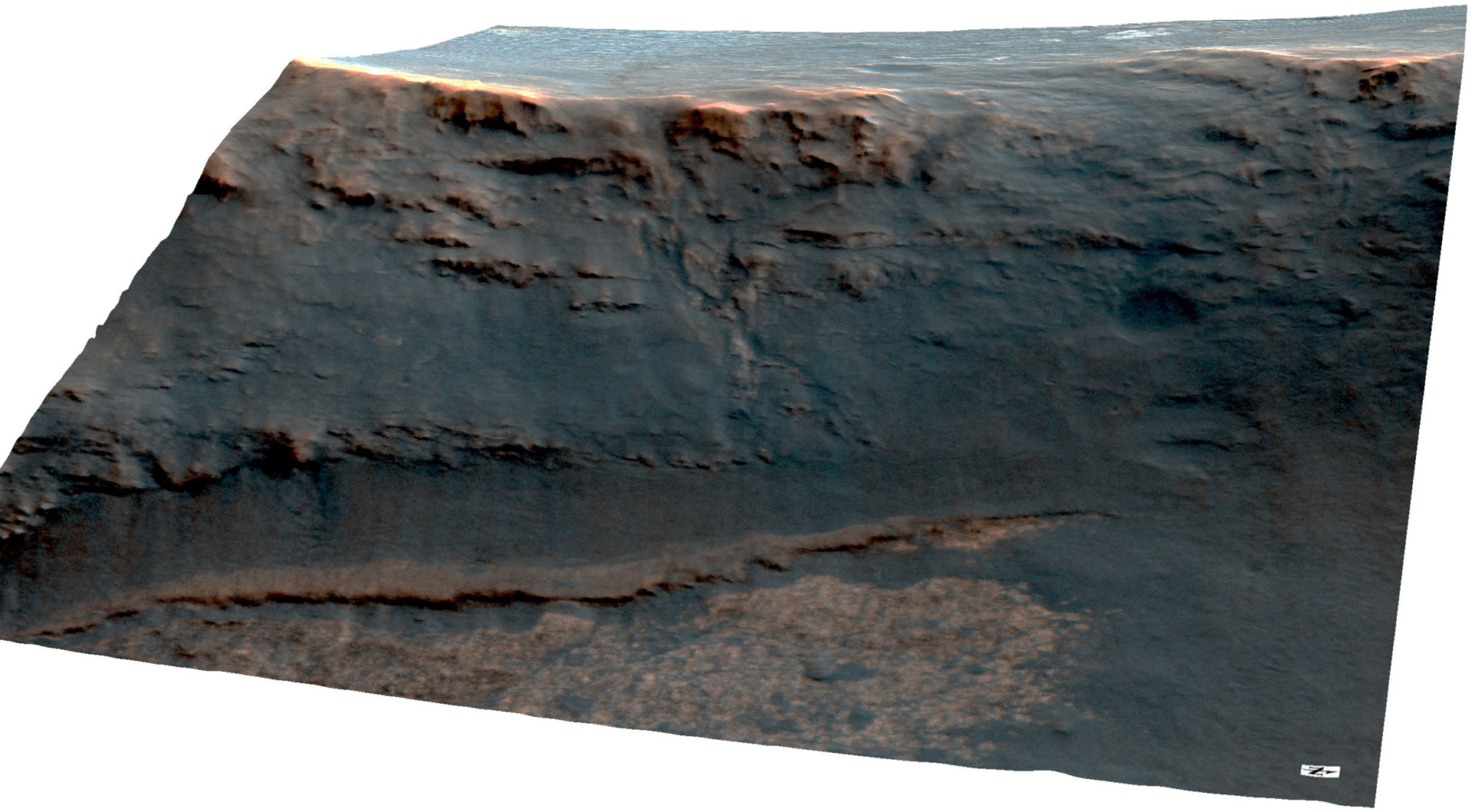

The rover’s prime directive in Perseverance is to take extensive imagery of the valley interior as she roves through it. These hundreds of images will be used to create a digital elevation model (DEM) that will reveal Perseverance in all its Martian glory in a simulated 3D view. “We’ll drive downhill at about 20 meters a clip and then spend time at each of those places doing 360-imaging with Navcam and targeted Pancam imaging, and when targets present themselves do some close-up work,” said Arvidson.

During the third week of August, Opportunity drove downhill or east to the second science stop, a small rise along the southern ‘wall’ or side of the valley, located about a third of the way down the valley. The second of seven tentatively planned science stops on a route that extends from the valley top to the bottom and the floor of Endeavour, this site is known simply as station 2

The work was easy enough for this ’bot and Opportunity was willing. But the deep freeze of the Martian winter was real and the robot had to use more and more energy just to stay warm. To meet operational demands, the rover began devoting two or more sols per week just to recharge her batteries.

Compounding the power situation is the fact that Opportunity lost use of her Flash or long-term memory a couple years ago. Since then, the robot has had to store her day’s work in RAM and offload it that same sol to Mars Odyssey, her mainstay communication orbiter, or the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), before she shuts down for the night, because RAM is volatile memory that doesn’t save data.

Nevertheless, with the support of her human colleagues on Earth, Opportunity was getting the job done. “The rover is doing fine, the team is doing a great job, and we’re just going to keep at it,” said Squyres then.

As the calendar turned to September, Opportunity was producing enough energy to survive and to work but the amount of energy she needed just to keep warm continued to increase as old man winter dipped the rover’s external temperatures to -90 degrees Celsius [-130 Fahrenheit], slowing the rover’s pace. “Winter is setting in and we’re getting cold,” said Nelson.

The ops engineers even considered turning on a back-up, never-before-used battery heater to help out their robot colleague in the Martian field. In the meantime, the robot braved the brutal temps and succeeded in completing her assignments at station 2. “We are imaging and we have even looked at a couple of targets, pebbles within reach,” said Project Scientist Matt Golombek, of JPL. “But things are slow going, because we’re approaching the dead of winter.”

The day of the least amount of sunshine, what planetary scientists call minimum insolation, would hit on Halloween. Then the winter solstice (in the southern hemisphere of Mars where Endeavour and Opportunity are located) would follow on November 20th, still a ways off.

So ‘slow’ was better than ‘no,’ and the scientists liked what they saw in the images trickling in from Opportunity. “The morphology of the valley is quite interesting,” Golombek said. “There’s a little more diversity of rocks here than what I think we expected.”

During the final sols of September, Opportunity worked on completing her imaging and APXS assignments on the station 2 target named Bernalillo, while the MER ops team members discussed sending the rover back uphill to an area near the first way station. The scientists had spotted some interesting bedrock the rover had driven through in her exit images. It looks to be a contact – “two different colored, bedrock units in direct proximity,” said Golombek – where, perhaps, two epochs of Mars collide. And one of the bedrock units has some particularly puzzling features.

With winter nipping at her wheels, a very dusty Opportunity roved into October and finished up the requested work at station 2, and then began the journey back uphill, to the contrasting outcrops. The MER team members named the site La Bajada, following the naming theme of stops along the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the old, 2,560-kilometer (about 1,591-mile) trade route between Mexico City and San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico. “There is something different between the bright, flattish rocks on the northern side and the lumpy, darker rocks on the southern side, so it is probably a geologic contact,” said Arvidson. “But we went back uphill because the northern or light-toned outcrop has some features that look like they were etched.”

The etching or scouring appeared to be small erosional tails, geological signs of an erosive force but they seemed to be pointing up hill. Since the favored theory is that Perseverance as a whole was carved by water in some form, and since water doesn’t flow up hill, at least not a hill as steep as the grade of this valley, the scientists wanted to check out these little tails even though they were but centimeters in scale. The objective was to get the rover in a secure and safe position over one of these etched rocks and check it out with her Microscopic Imager (MI) and her chemical sniffing Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS).

Backing upslope in Perseverance would be easier said than done. Admittedly, Opportunity is getting on in years and has a few driving limitations, but nothing that would stop her from this assignment. “The biggest trouble,” said Stroupe, “is this terrain is very steep.”

While pumpkins were populating planet Earth, the rover struggled dutifully to reach the chosen etched rock. She even popped two wheelies during her roboculean efforts. “The key point right now,” said Squyres, “is Opportunity is performing beautifully as we ask it to do some very complicated things.”

Once all six wheels were firmly back on Martian ground, the robot field geologist got to studying Mesilla, a target spot on a northern, light-toned outcrop rock with ‘tails’ to tell. As the robot worked, Mars delivered its October surprise.

Just as MER Power Team Lead Jennifer Herman, of JPL, had cautiously suggested might happen in the weeks earlier, the planet produced a gust or two or three of gentle winds that lifted up from the floor of the crater and cleared some of the accumulated dust from the rover’s solar arrays. “We've had a little dust cleaning,” Herman confirmed. “And we are hoping for more.”

The winter cold continued to slow ‘life’ on Mars, but Opportunity pressed on. She spent November sleuthing the scenes with her cameras for any visual clues or evidence that could reveal what carved this unique valley feature billions of years ago, what formed its braided grooves or channels, and what scoured its outcrops. The rover used her robotic arm or Instrument Deployment Device (IDD) to focus up close on Mesilla with her MI and then APXS.

From flowing water to a muddy debris flow, to ice and ice melting into water, or water coming out of fractures, wind, or a combination of these forces, the MER scientists were still considering multiple hypotheses to explain how the valley and its distinctive features were formed. Perched over Mesilla, the rover scored a small, partial win for wind.

“It was the Battle of La Bajada,” Squyres said. “In the end, the team absolutely nailed it. We have a mosaic that very clearly shows multiple erosional tails pointing up hill … one of the most difficult and beautiful microscopic image mosaics in the history of this project. And we made a fundamental finding, one that was enabled by some very, very tough driving.”

Significant as this finding was, it revealed nothing about how the valley itself was created. There was a lot more work to do. From La Bajada, Opportunity headed back down the valley and onto another north-facing slope or lily pad.

During the ensuing two weeks, the solar powered robot soaked up as much winter sunlight as possible, and with a little more help from the Martian winds, Opportunity made it through winter solstice without incident, despite outside temperatures that dropped to -96.12 (-141.01 Fahrenheit). “We passed the winter solstice on November 20th and power levels have been improving,” Callas confirmed. “We’ve had some dust-cleaning events, which is helping increase power.”

Opportunity worked through the Thanksgiving holiday, mostly on taking images of everything around, while her human colleagues took a break. Then, the robot trundled farther into the valley to another north-facing slope, stopping about 15 meters away from where a large trough splits, the bifurcation zone, as the geologists define it.

From her vantage point, the robot snapped away, visually documenting the fork in the road just downhill. “Opportunity is in good health and everybody on the team seems to be as well,” said Squyres. We’ve got a lot to be thankful for this year.”

Opportunity spent the first week and a half of December conducting an extensive Pancam color stereo imaging campaign, taking large panoramas almost every sol. The skies overhead were lightly hazy, Tau registering 0.417, typical for winter. With a solar array dust factor of 0.624, the rover’s power production was on the increase and the robot was boasting energy levels hovering around 400 watt-hours of energy.

Winter however is not over. Opportunity did have to devote her Sol 4933 (December 9, 2017) to recharging. Then, the following sol, the rover took off, driving 8.4 meters (27.55 feet), approximately east, down the valley to a modest energy lily pad just uphill from the fork in the road.

Beyond this point, the trough or channel splits into a left and right or north and south fork, leaving a hummock or mesa or island in between. From this stop, the rover and her team can see right into both forks. “We wanted to image this hummock or mesa, because there are hypotheses that it might be a gravel bar from an ancient river or something else and we wanted to create a mosaic that covers the north fork and the south fork,” said Arvidson.

There’s no shortage of weird geological Martian things to check out here. The trough where the rover sat for most of December is distinctive in its own right, marked with “a crazy pattern in the regolith,” as Arvidson described it. “It looks like ripples with tops that are a concentration of the little rock pebbles, kind of shaped in what I call stone stripes that are lined uphill and downhill. We’re not quite sure what’s done this, so it’s really interesting,” he said.

Being there and given the holidays were rushing in, when Opportunity wasn’t shooting the scene around her, she investigated a target spot on one of the ripples topped with little rocks, which the team named Carrizal. On Sol 4941 (December 17, 2017), the robot geologist took the pictures needed for a MI mosaic, and then placed her APXS on that target.

Opportunity also continued imaging the hummock and the fork scene through the Christmas break from her vista point just ‘upstream’ of the ‘fork,’ and worked in some other assignments too, including a color twilight panorama with her Pancam on Sol 4942 (December 18, 2017). “Once we’re done with the holidays, we’ll move on down the valley,” said Squyres.

But down – where? The team has been scrutinizing the rover’s images to decide which fork to take. Although team members have been quoting Yogi Berra’s advice: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it,” decision time is near. “Everybody’s keen on going to the north where it looks like there is more variety, which is going to tell you more about process,” Arvidson said. The team is scheduled to decide in the New Year.

Most of the MER scientists are still confident that Perseverance was forged and shaped by water. The question that remains is: can they find the evidence to prove that? “There is a lot of room there is a lot of leeway as to what the water to rock ratio was,” Squyres said. “Was it a muddy debris flow? Was it a clear flowing stream? There is a lot of uncertainty there. That’s what we’re working on.”

The answers or at least some of them are here somewhere. “It could be in the shape of the hummock or island and what’s been happening to the rocks there,” ventured Arvidson. For Squyres, what’s interesting is “the stuff on either side of it,” as he put it. “Because what’s on either side is the valley. If the valley weren’t there, it would be all hummock or mesa,” he said.

All in all, 2017 was another very good year for Opportunity and the MER team. “Mars is never dull,” said Bellutta. “It keeps you on your toes all the time. The year went by quickly and I am glad that we are on the other side of Winter 8.”

Come January 24, 2018 Opportunity and the team will check off their 14th Earth year of surface ops, and then keep on roving into Year 15. “Mechanically, things have been holding together really well lately,” said Squyres. “Knock on wood but we’ve been doing pretty well. We’re past the solstice and the power is starting to come back up. The skies have been pretty clear and the solar array is fairly clean. We’re ready.”

Spirit Remains Silent at Troy

Stuck in the sandy edge of a shallow hidden crater along one side of Home Plate, Spirit phoned home on Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010) just before she went into a planned hibernation.

The robot that came to known as the-little-rover-that-could had worked for more than six Earth years and drove 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles) in some of the harshest Martian terrain the mission will ever encounter. She was the first rover to climb a mountain, the first robot to take pictures of dust devils on the surface of Mars, and the first to find evidence for near-neutral water on Mars. In those 6+ years, Spirit literally defined MER mettle.

For the next year, NASA-JPL radiated more than 1,300 commands to Spirit as part of the recovery effort to elicit a response, any response. Hearing nothing in all that time, NASA officially concluded recovery efforts on May 25, 2011. The remaining, pre-sequenced ultra-high frequency (UHF) relay passes scheduled with the Odyssey orbiter completed June 8, 2011. No one has heard from Spirit since.

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth