Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 02, 2014

Mattias Malmer's amazing 3D views of Churyumov-Gerasimenko

I'm thrilled to be able to share with you all a spectacular set of images of Rosetta's comet, produced from NavCam data by a master space image processing enthusiast. Mattias Malmer has been working with space image data for many years, producing iconic images -- his version of the Mariner 10 global view of Venus is my go-to image of that planet. He dropped out of the space image processing scene for a few years, but the amazing Rosetta NavCam views of Churyumov-Gerasimenko have drawn him back. Behold:

Churyumov-Gerasimenko: Into the Light This movie of comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko rotating was generated by draping the September 24, 2014 NavCam photo over a 3D model of the comet.Video: ESA / Rosetta / NavCam / Mattias Malmer

Here are two more videos, for which you'll need a pair of 3D glasses:

In fact, Mattias has processed 20 NavCam images of the comet into 3D views. I've embedded three of them below, but you can download the entire set here in a single Zip file (12.6 MB).

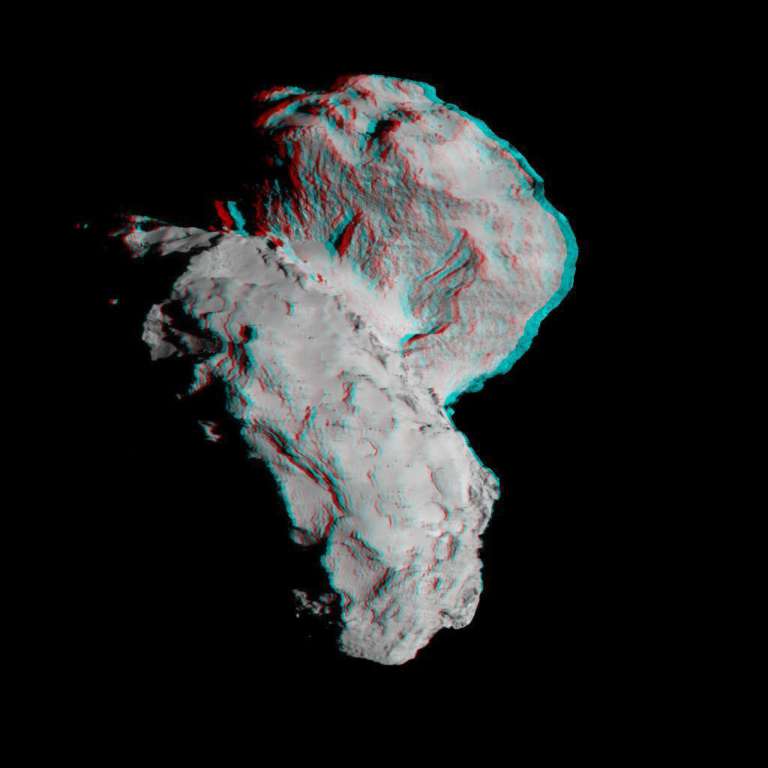

Here's the comet at its duckiest:

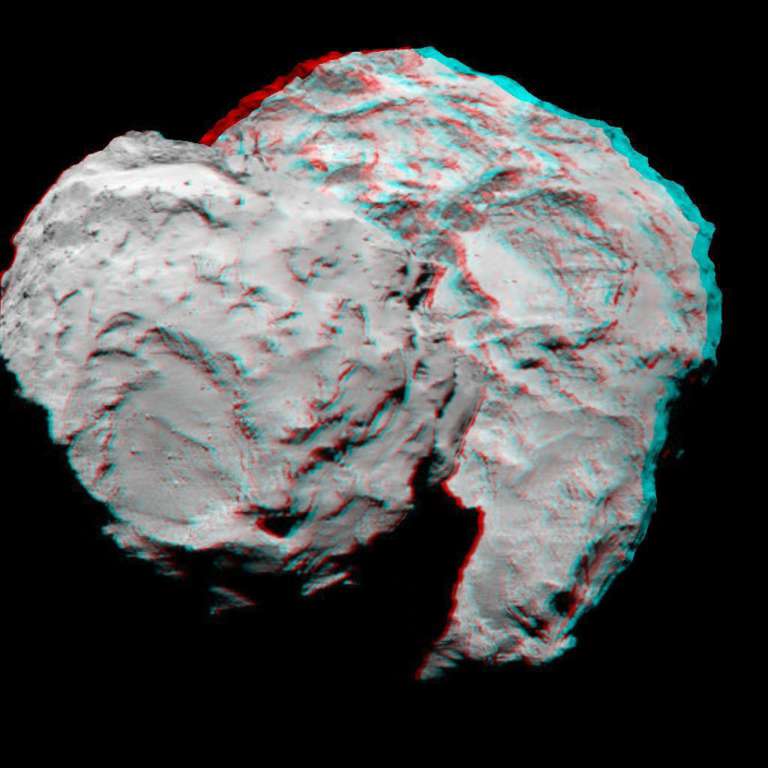

A view facing the Philae landing site:

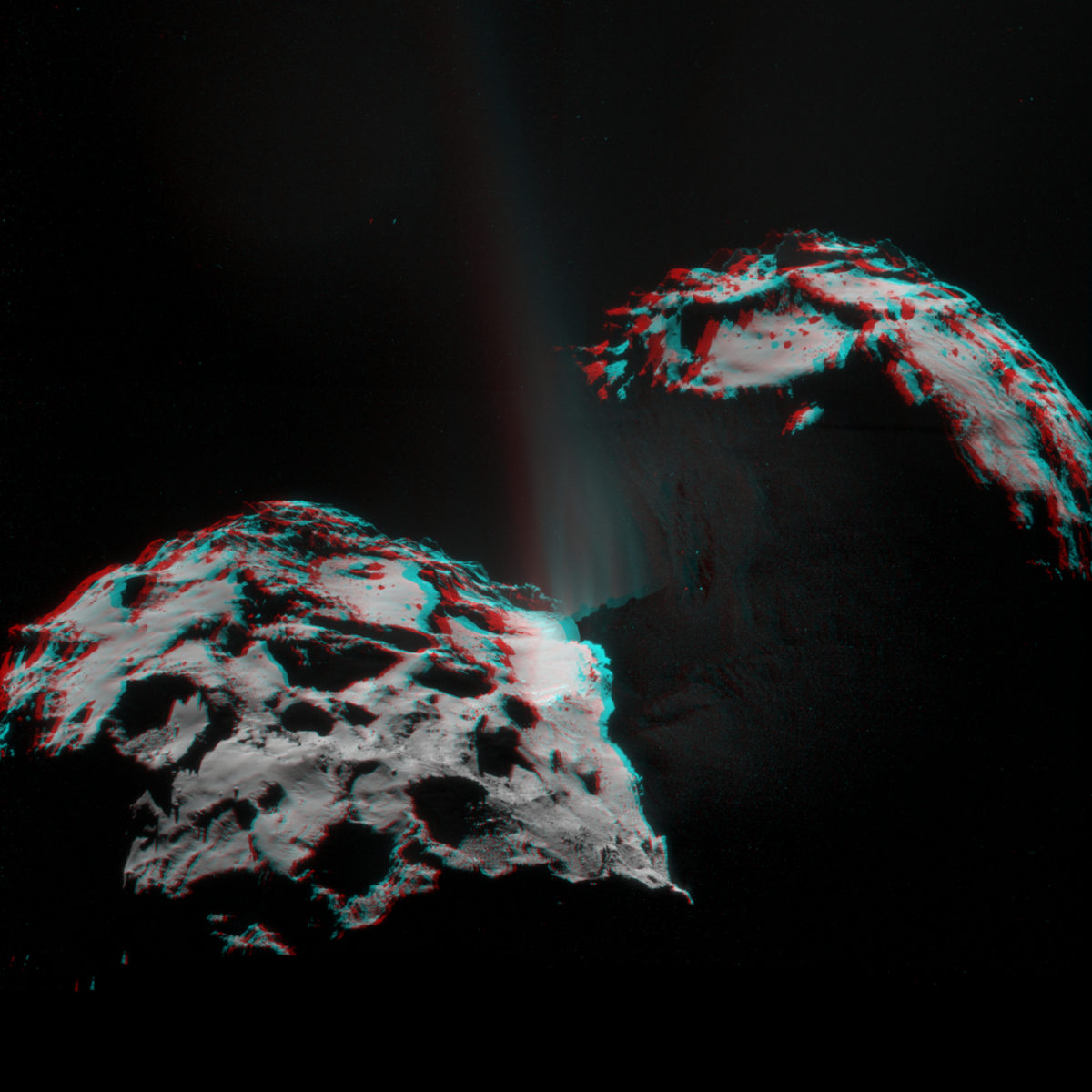

And a gorgeous view generated from the latest NavCam image, released today:

How did he create these amazingly dimensional views? Mattias is a 3D digital imaging professional, and he brought professional tools and techniques to this data set. He explained to me:

These stereo views were made by projecting the original images over a digital model of the comet. This model was then rendered from two slightly different viewpoints to create the different perspectives for each eye. These two views were then combined into anaglyphs.

The digital shape model itself was slightly more challenging to create. To build it I used several techniques. The two most important are "stereo correlation" and "space carving". Both of these techniques are based on analyzing features in the source images in relation to the same feature in other images. They both hinge on the fact that you know the exact position and orientation of the cameras that shot the images. This information is possible to reconstruct using photometry. There are a few software packages out there that can help in doing that. I used "image modeler".

With the camera positions and pointings in hand, I could can then go on to reconstructing the comet itself. First I roughed it out using space carving. Imagine having a block of clay in front of you. Then you use an overhead projector placed where one of the cameras was in relation to the comet. You shine an image of the comet's silhouette shape onto the clay. Then carve away all the clay not being lit by the sillhouette. This will leave you with a cylinder shaped object that only looks like our comet if seen exactly from the projector's view. So then we go on and move the projector to a new camera position, light it with the corresponding silhouette, and carve our clay. And we do this for as many viewpoints as possible. What's left is a chiseled but fairly accurate representation of our comet. In the computer i did this not by carving in clay but by writing code that did billions of tests to see if points in a 1000 by 1000 by 1000 grid were inside or outside the silhouettes.

I further refined this chiseled shape using dense stereo correlation. We are blessed with one really great pair of OSIRIS images that were shot a short time apart and therefore depict the comet from two slightly different viewpoints. By having the computer compare those images, you can calculate how much each feature in the image moved between the two frames. And knowing that, you can use trigonometry to calculate those features' position in space. With the quality of the OSIRIS images we get very good data. I used this high-quality stereo data to refine the crude space carving model in the areas with coverage.

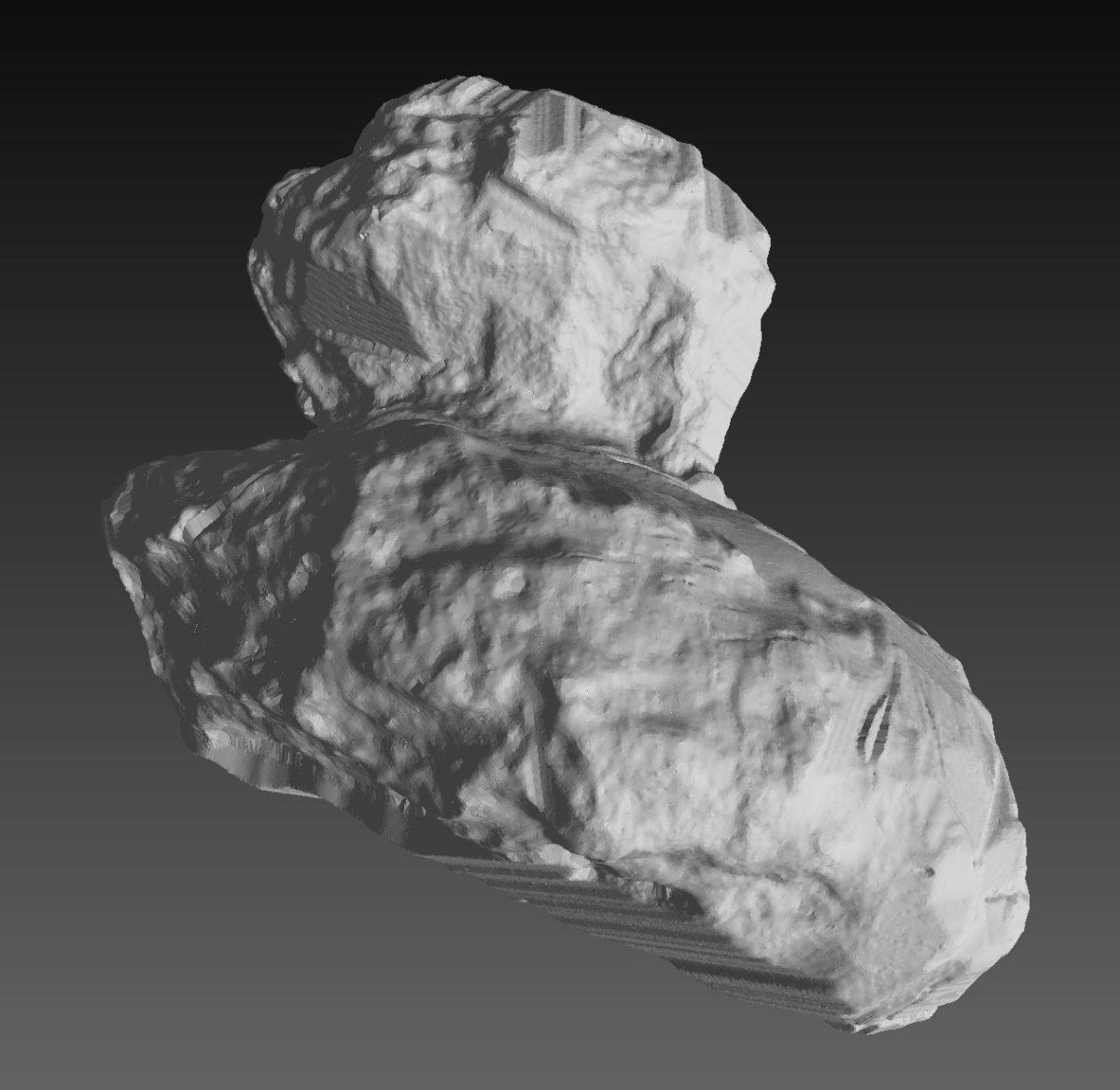

Here's a view of what the shape model looks like with no photograph draped over it. You can see the virtual chisel marks created by the process that Mattias describes above. In some places, the texture is finer. That's where he was able to refine the model with the single OSIRIS stereo pair.

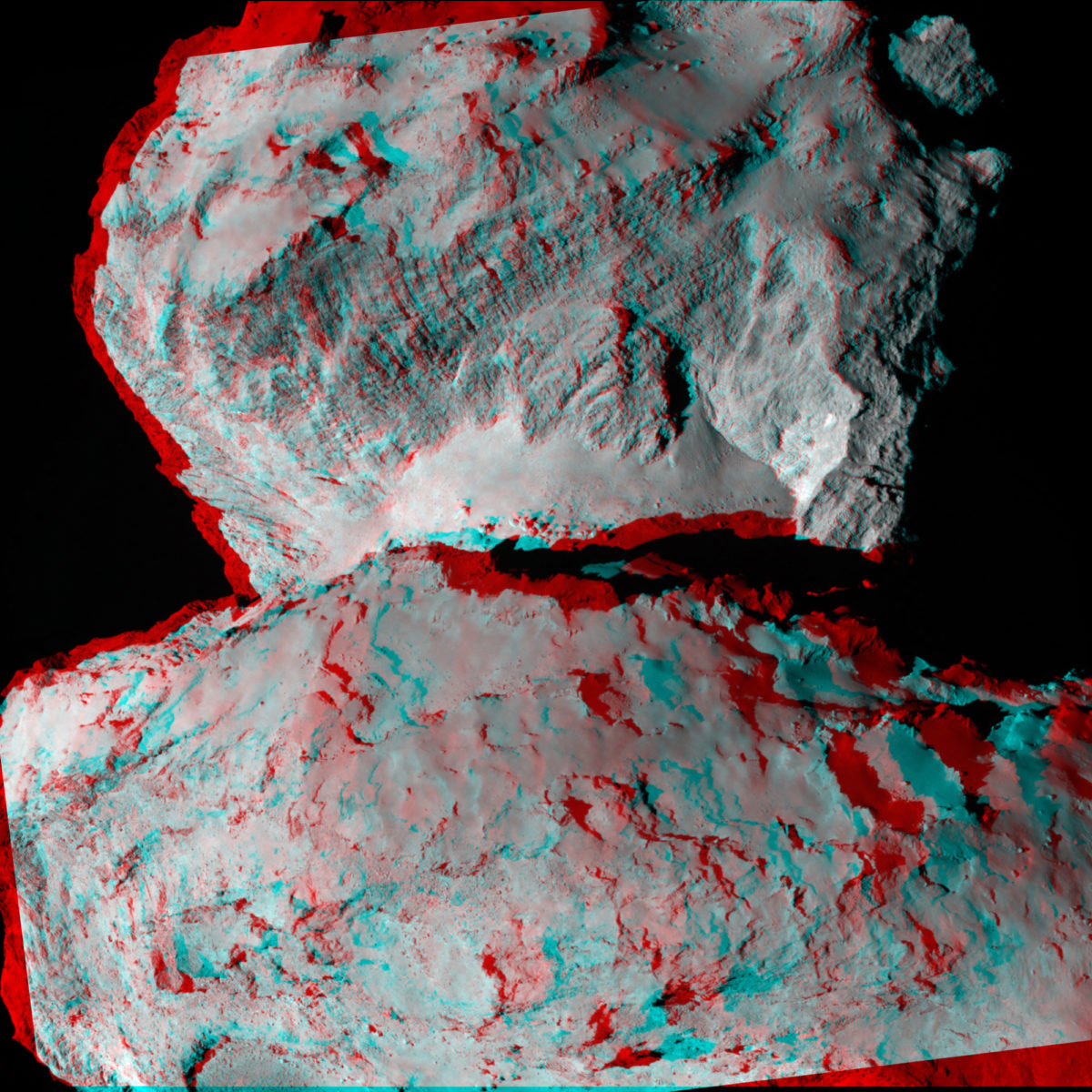

Below is the single 3D image that has been released by the OSIRIS camera team. This is the only 3D image in this entire post that's made from two actual photos taken from different perspectives. It's amazing how much Mattias has managed to accomplish with space carving of NavCam images and stereo correlation on this one OSIRIS stereo pair. Mattias is desperate for more 3D images that he can use to improve his shape model, especially in areas not visible in this OSIRIS image pair. In the grand scheme of things, we don't have long to wait; even if no more 3D OSIRIS images ever come out in press releases, the formal data release is scheduled for May 21, 2015 (or six months after the planned landing of Philae on November 21). Soon!

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth