Jason Davis • Apr 26, 2017

The first Space Launch System flight will probably be delayed

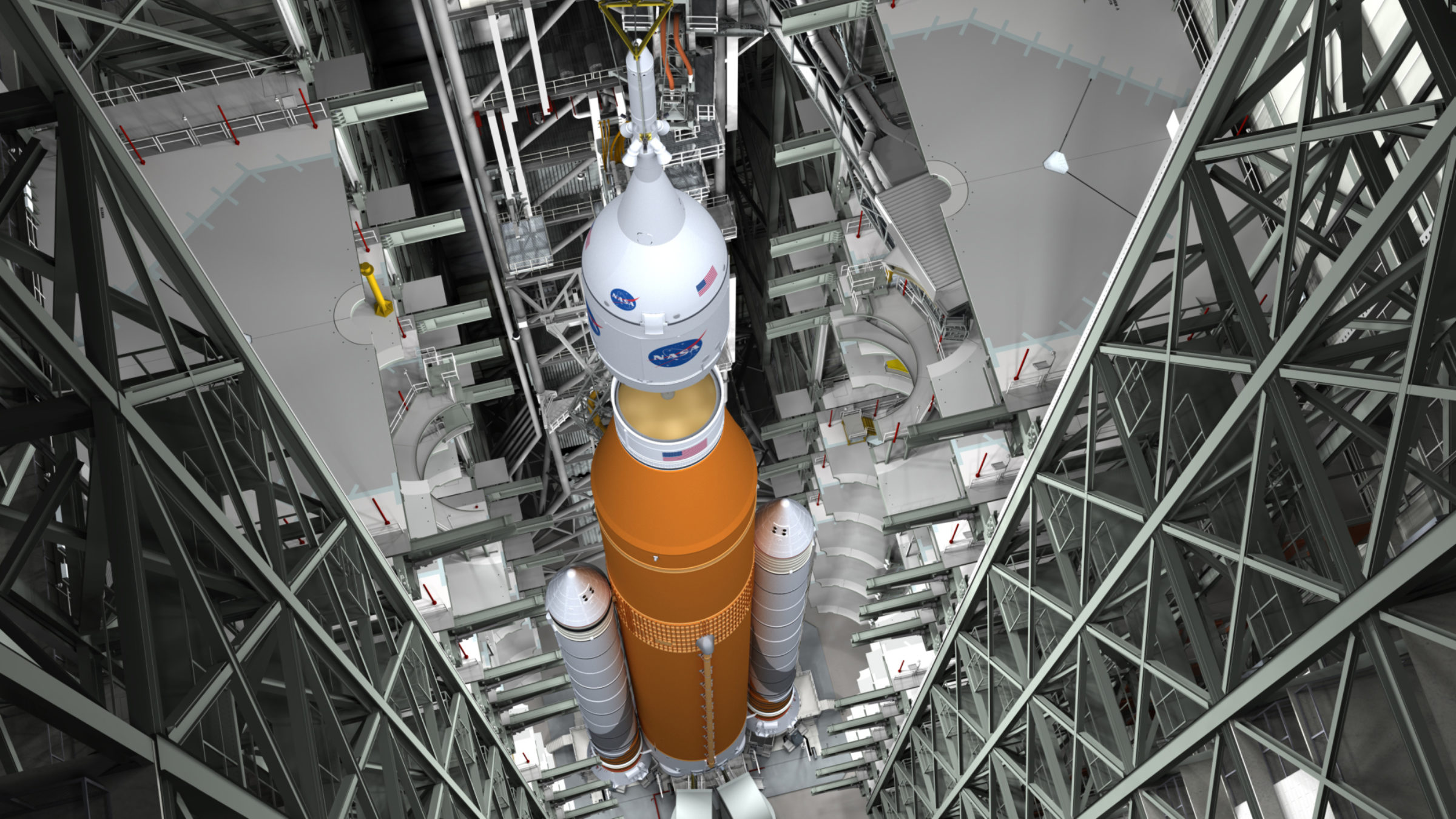

It's looking likely that the first flight of NASA's new heavy lift rocket, the Space Launch System, will slip beyond its November 2018 launch date.

The space agency has yet to announce any official schedule changes. But a recent report by NASA's Office of Inspector General, along with dates provided by internal sources, an agency-wide schedule review currently in progress, and welding challenges involving the core stage liquid oxygen tank, all point to a probable delay.

Last year, after our Rocket Road Trip to NASA's southern spaceflight centers, we noted that despite an impressive amount of progress on infrastructure upgrades, the big rocket's launch schedule was razor-thin. Now, following a February tornado that disrupted operations at the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, all signs are starting to lean towards a slip.

The situation

On April 13, NASA's Office of Inspector General, or OIG, issued a report on the agency's efforts to send humans beyond low-Earth orbit. According to that report, SLS, Orion and their associated ground systems should be carrying cost margins of 10 to 30 percent, and schedule margins of 30 to 60 days per year.

But in terms of cost margins, SLS and Orion are down to 1 percent, and ground systems are at 3 percent. For schedule, SLS and ground systems have just 30 days of wiggle room, and Orion has already incurred a five-to-ten-month delivery delay on its European-built service module.

NASA previously planned to have the first completed SLS core stage shipped from Michoud to Stennis Space Center in time for an all-up test firing this December. Following the test, the stage would be shipped to Kennedy Space Center by the end of February 2018.

But the OIG says that shipment has been delayed to March or April. When I asked Marshall Space Flight Center officials if the test firing was still on track to happen this year, they said NASA was currently "reviewing the production schedules across the enterprise," and a date for the test-firing would be set thereafter.

Software development is also behind schedule, according to the OIG. Ground systems software won't be ready until May 2018, while SLS and Orion software readiness isn't predicted until June—all roughly about a year's delay from previous estimates.

The SLS mobile launch tower isn't currently scheduled to roll into the Vehicle Assembly Building until July. That will leave about four months for NASA to assemble SLS, complete integrated testing and roll the rocket out to the pad in time for a November 2018 launch.

At the same time, NASA is studying whether or not crew could be added to the first flight, which would push the launch date beyond 2018. But even if the first mission remains uncrewed, at least one schedule provided by internal sources already shows a projected launch date of 2019.

What happened?

The programs' cost and schedule margins seem to have evaporated for the same reasons other major new launch vehicle programs are often delayed: Unexpected issues of varying severity crop up, and over time, these cascade into a full-blown schedule slip.

In Orion's case, it's the European-built service module, which is based on the Automated Transfer Vehicles that carry cargo to the International Space Station. In 2015, engineers and astronauts at NASA's Johnson Space Center noted concern over the design of the ATV's propellant system, which has no failsafe redundancy in the event of a catastrophic leak. (One flight director called the situation "totally unacceptable" for ensuring crew safety.) The module's design was changed, but this led to a five-to-ten-month delivery delay.

At Michoud, Boeing engineers first had to fix a misaligned tower at the Vertical Assembly Center, which created minor delays. Now, a welding anomaly discovered on a core stage liquid oxygen tank test article threatens to delay things further.

"The (SLS) team studied the first weld confidence article and panels, and after testing, some of the welds did not meet NASA’s rigid quality and safety criteria," ageny officials said in a statement.

"Manufacturing of the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen tank is pushing the state of the art for self-reacting friction stir welding of thicker materials," the statement said. "These tanks must have thicker walls—greater than half an inch thick, than the other parts of the core stage, and NASA has not previously welded tanks at this thickness with self-reacting friction stir welding."

The core stage liquid oxygen tank has thicker welds than the hydrogen tank, which has already been completed. After discovering problems with the oxygen tank confidence welds, Boeing and NASA refined their technical parameters and processes, and welded together a new oxygen tank barrel and dome section for testing.

The results looked good, so engineers built a new liquid oxygen qualification tank. That tank shows no sign of leaks, and is now being shipped to Marshall Space Flight Center for structural testing. If the tests go well, construction of the final flight article can begin.

But none of this bodes well for the already tight schedule the program is facing.

Stack, test and launch

Assuming everything goes perfectly from here on out, and NASA is actually ready to start core stage stacking in July 2018, is four months enough time to get ready for launch?

Historical precedents show that's unlikely.

The last new rocket to come online at Kennedy Space Center (not counting the Ares I-X test flight in 2009) was the space shuttle, in 1981.

In 1979, the test orbiter Enterprise was mated to a fuel tank and solid rocket boosters in the Vehicle Assembly Building, and rolled to the pad for three months of integration testing. At that point, the maiden flight of space shuttle Columbia was still scheduled for November 1979.

But Columbia didn't even make it inside the VAB until November 1980, owing to tile woes, engine testing problems, and an array of last-minute integration issues.

The shuttle finally traveled to the launch pad in December, completed an engine test-firing in February 1981, and flew in April—marking at least a 17-month delay during the run-up to launch.

Fortunately for NASA, SLS uses flight-proven shuttle engines, there won't be an on-pad test-firing, and Orion shouldn't have any tile problems. Nevertheless, there are bound to be last minute testing and integration snags to get the most powerful rocket since the Saturn V ready to fly.

Black eye?

If the launch slips, how big of a black eye will this be for the program?

It could depend on the duration. If the delay is more than six months—meaning, May 2019—NASA is required by law to inform Congress, which could lead to public hearings and other unwanted publicity.

But thus far, neither Congress nor the White House has signaled any desire to make large-scale changes to NASA's deep space exploration plans. This position was bolstered further Monday during President Trump's call to the International Space Station, in which he showed enthusiasm for NASA's current Mars-oriented plans.

Trump's full fiscal year 2018 budget is expected to be released less than a month from now. If NASA's portion reflects the so-called "skinny" version released in March, which endorsed a status quo approach to the agency's human spaceflight program, even a full-year delay might not have much impact.

In fact, budgets are often a time when federal agencies release updated timelines and lay out new program details.

Will we see a new SLS launch date soon?

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth