Preparing America’s Spaceport for NASA’s New Rocket

Written by

Jason Davis

June 22, 2015

The first impression you get walking into NASA’s Vehicle Assembly Building is that this does not look like a place where rockets are assembled. It’s dark and dusty, and the smell of oil fills the cool, damp air. You hear loud machinery in the distance, accompanied by the beep-beep-beep of trucks in reverse. Construction workers dart in and out of the shadows. A hodgepodge of dusty space shuttle mission placards—including the final missions of Challenger and Columbia—serve as reminders that actions taken here can literally be a matter of life and death.

But there’s also a sense of purpose in the air. With the shuttle program now four years gone, the mourning period appears to be fading. Conversation coalesces around what comes next. By late 2018, this mecca of spaceflight must be ready to host NASA’s next rocket, the Space Launch System. There are deadlines to meet. The civil servants and contractors have determination in their eyes. And although NASA lists November 2018 as the first SLS launch date, Kennedy Space Center doesn’t appear to have received the memo—everyone here says September is the correct month.

To fly SLS, NASA needs an assembly building and a launch pad. That’s a bigger deal than it sounds; launch preparations can be logistical nightmares. The agency’s Ground Systems Development and Operations Program—GSDO, or simply ground systems—has its hands full. So much so that NASA’s Office of Inspector General released a report saying the program, which will receive $1.4 billion from 2014 through the first SLS launch in 2018, may not being ready in time. Ground systems are the dark horse of SLS delays.

The Vehicle Assembly Building is huge. It’s easy to spot from miles in any direction along Florida’s Atlantic coast. In case you aren’t already impressed by the time you arrive, NASA has signs and fact sheets to further astound you. Largest doors in the world! Almost 100,000 tons of steel! The biggest-ever American flag on the exterior, complete with six-foot stars! Inside the VAB, it’s a bit harder to gauge the scale of the building. Photos don’t do it justice, but neither do your eyes, really—the twisting towers of steel and concrete throw off your depth perception.

Near the entrance, I meet Darrell Foster, the chief of project management for GSDO. Foster and I spend a few minutes leveling our respective knowledge levels to the point where we can speak the same language. The best project managers do this well, since they’re constantly interfacing with both engineers and managers. Before long, we’re strolling through the VAB, chatting comfortably.

The OIG report supported a suspicion among some space policy experts that during the past few years, NASA spent too much cash on SLS and Orion—the spacecraft that will carry astronauts—while shortchanging ground systems. Foster doesn’t agree. "If you don't have a rocket, you don't have a need for ground systems," he says. "So they're constantly trying to balance between the flight vehicle and the ground systems."

By "they," he means NASA’s Exploration Systems Division at the agency’s Washington, D.C. headquarters. This was another OIG complaint: SLS, Orion and GSDO are managed separately, yet they have tight interdependencies. All three must work together for SLS to fly. This is a departure from the shuttle era, when Johnson Space Center, which manages the International Space Station, oversaw the entire program.

"Even with shuttle you had different projects," Foster says. "We didn't call them separate programs. There was a booster project, there was an external tank project, there was an orbiter project and there was a ground systems project, so to speak. In shuttle, the program was at JSC. The stuff at Kennedy was considered a level three, or a project. So there were still multiple interdependencies."

It gets the most complicated, Foster says, where there are actual physical connections between the three systems, such as the launch tower umbilicals that feed communications, fuel and gases to SLS and Orion up until the moment the vehicle lifts off from the pad. Umbilical work is one of the biggest hurdles remaining on the launch schedule, in both Foster and the OIG’s mind. "That is probably our critical path right now," he says, "because they're very complicated and there's lots of structural testing we have to do. Anytime you have a T-0 disconnect, it's very complicated from a load standpoint."

We stop at a yellow utility crane sitting on the VAB floor. The crane, which normally attaches to rails on the ceiling, was here when I visited last December for Orion’s first test flight aboard a different rocket system, United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV Heavy. The crane can lift 175 tons, but there are larger ones that can handle 250 and 325 tons. In order to rotate a rocket section from the horizontal to vertical position, you often need multiple cranes to hold things steady, lest a piece of the Space Launch System find itself swaying back and forth like a Florida palm tree.

The crane has been completely refurbished, Foster says. It has new gear boxes, lifting fixtures and control systems. Even the operator cab got an overhaul, which seems like a reasonable expenditure for the person entrusted with lifting multimillion dollar rocket parts.

"These guys that run these cranes know what they're doing. You can put an egg on that cone," Foster says, gesturing to an orange construction pylon, "And those guys will lower that hook down on top of the egg without cracking it." Later, I ask another NASA official if that was an exaggeration; a John Henry-esque tall tale stemming from the good ol' days. I was assured the egg challenge is still a thing, and in fact, NASA’s VAB literature mentions it.

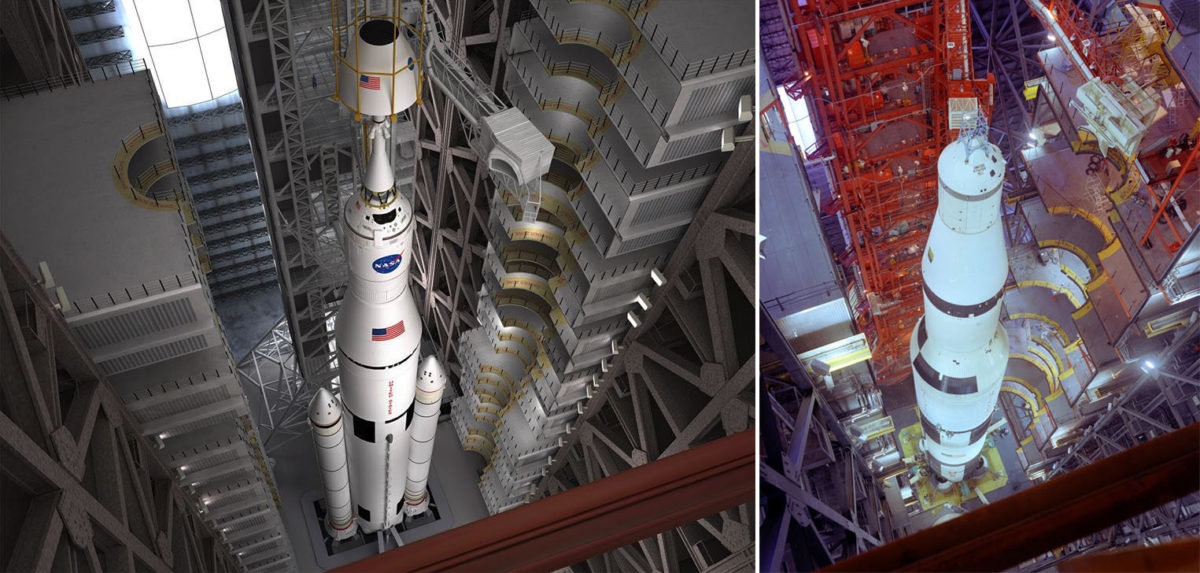

The Space Launch System will be stacked, rolled to the pad and launched the same way NASA processed its Saturn V rockets before sending them to the moon in the late sixties and early seventies. Edsel Sanchez, the Vehicle Assembly Building site project manager, walks me over to high bay three, where SLS will be assembled. The bay has been stripped bare from the foundation to the ceiling. It is cordoned off with a twisted, yellow-black rope. One of the VAB’s massive doors is cracked open, throwing a beam of sunlight onto a concrete floor littered with construction materials. Small utility trucks scurry around, and it’s noisy.

"Keep in mind this building was designed for Apollo," Sanchez says, as we survey the scene. "This is the third vehicle that we're going to process in this building, so we've had to modify a lot of our systems."

Each corner of the VAB’s main, rectangular structure contains a high bay and a vertical door; those doors open to the east and west. A transfer aisle runs north-south through the building’s center, and the space between each side’s two high bays contains support towers with rooms for everything from offices to testing equipment.

In theory, all four high bays can hold a fully stacked rocket. The building was designed with hurricane protection in mind; a Saturn V or shuttle could be wheeled back inside to weather out a storm while others were being processed. During the shuttle program, only the east-facing high bays—one and three—were used to stack vehicles. Bays two and four, on the west, were used for storage and other processing tasks, such as external tank preparation. NASA recently offered up bay two for rental by other private rocket companies.

SLS will roll into the VAB transfer aisle, piece by piece. Each component will be crane-lifted into high bay three for stacking. (The bays are partially enclosed by the building’s superstructure; thus, pieces must be lifted up and over giant, crisscrossing steel braces.) Inside the bay, rail-mounted platforms slide up to the vehicle to give technicians access. The platforms are shaped to fit the outer edges of the rocket, and are positioned at strategic heights that match critical systems.

"We had the existing platforms that we could modify from Apollo to accomodate shuttle," Sanchez says. "But we couldn't modify shuttle for SLS, so we said, ‘You know what, this is the time to start fresh, with a brand new design.’" All of the shuttle platforms in high bay three have been removed. To offset construction costs, says Foster, the contractor got to keep the steel for recycling.

The first set of new SLS access platforms has already arrived. They sit outside the VAB, awaiting installation. We go outside to have a look, but Foster and Sanchez lower my expectations ahead of time. From ground level, the platforms don’t look like anything more than piles of steel shimmering in the humid Florida heat.

Just north of the VAB is the Mobile Launcher, a repurposed space shuttle stacking and launch platform that now sports a tower akin to the one used for Saturn V rockets. It’s here that I meet Mike Canicatti, the Mobile Launcher contracting officers' representative. We squint and shield our eyes as Canicatti points out some ML particulars; the sun is already as high as the 108-meter tower. A persistent hissing comes from the platform’s raised deck; workers are sandblasting and painting, and using what’s essentially a giant shop-vac to clean up the mess.

To stack SLS, the entire Mobile Launcher will be picked up by Crawler-Transporter 2, one of the tank-like vehicles used for hauling rockets since the Apollo era. The crawler, which moves in both directions, will slowly carry the ML into high bay three. "That crawler doesn’t do a U-turn very easily," Canicatti says. It will plop the ML into position with its tower facing the VAB’s outer door. The crawler can then, as Foster puts it, "crawl out from underneath it, and go do other things." An image comes into my mind of the big machine lumbering toward the Atlantic with sunscreen, a beach towel and a fruity drink with a small umbrella.

Crawler-Transporter 2 has, like most of the other KSC infrastructure, been the target of a massive overhaul. It’s parked across the transfer aisle from the SLS high bay, and as we walk over to have a look, we pass colossal gearboxes lying on the floor.

"This thing just turned 50 a couple weeks ago," Foster says. "We had a birthday party for it and everything. This, to me, is the ultimate Tonka toy. It is the coolest thing that ever moved."

He rattles off a dizzying array of upgrades that have been performed. From steering arms to gear boxes, everything has been reinforced to handle SLS, which, in its initial form, will weigh 2,500 metric tons at liftoff—that’s up from the space shuttle’s 2,000 tons. The retrofit process seems complex, so I ask: Why not just start over? For that matter, why not just level the VAB entirely?

"It's like an old house," Foster says. "Sometimes it's easier to bulldoze and build new. We do that when there's a cost benefit. To rebuild this building is over a billion dollars. We've done the trades and there's a cost-benefit analysis. To rebuild one of these," he says, gesturing to the crawler, "I don't know what the price is on it, but it's way more than the money we've invested in it. I think it's something like $40 million in this. You can't buy one of these for $40 million, I can guarantee you that."

To get a look at a group that is, in fact, starting from scratch, I climb into a white government van with Kathleen Ellis, a longtime NASA public affairs official. The last time I saw Ellis, she was herding photographers around the roof of the VAB the morning of Orion’s inaugural test flight. Ellis and I are headed to pad 39B, where the crawler will bring the Mobile Launcher and SLS for liftoff in 2018. But we’ll also drive by pad 39A, a former shuttle pad that has now been leased to SpaceX. From here, the private company plans to launch Falcon Heavy, a triple-core version of their Falcon rocket capable of carrying 53 tons to low-Earth orbit. That’s almost double the capacity of any vehicle operating today, but shy of the 70 tons the first SLS version can do.

Unlike NASA, SpaceX will assemble their rockets horizontally. Their VAB equivalent is a large, storage shed-like building emblazoned with a SpaceX logo and American flag, sitting barely a stone’s throw from pad 39A. (NASA’s VAB, on the other hand, is almost seven kilometers away from pad 39B by crawler.) When a Falcon Heavy is ready for flight, SpaceX will roll it up the hill, raise it vertically, and launch it. The space shuttle’s old service structures still loom large over the pad, but they will go mostly unused, and demolishing them doesn’t make much financial sense, according to a SpaceX engineer I spoke with that works at the construction site.

SpaceX started work at pad 39A later than NASA started work on SLS, yet they plan to launch sooner; the first Falcon Heavy demo flight is scheduled for later this year. Around the Cape, SpaceX seems to be regarded with a mix of wariness and respect. The company represents a threat to business as usual, and in many ways, SLS is the epitome of old-guard rocketry. Yet NASA has SpaceX to thank for reliably shuffling cargo to the International Space Station, and it’s hard not to appreciate the youthful exuberance the company has injected into the Florida coast.

Ellis and I arrive at pad 39B, but we hit a minor roadblock in the office of the pad leader, who didn’t get the memo we were coming to visit. Ellis deftly clears up the miscommunication and gets us badged; if it says on her itinerary she’s taking a reporter up to the flame trench, then up to the flame trench she will go. As we drive up the pad ramp, I can’t help but feel a little giddy. This is the one of the only major KSC facilities I’ve never visited. It was ground zero for the shuttle launch that inspired me as a child, Discovery’s 1988 post-Challenger return-to-flight mission. From the raised pad deck, you can see for miles in all directions. To the east, the Atlantic; to the southwest, the Vehicle Assembly Building—smaller now, but still quite imposing. (In fact, officials say the "blast zone" for upgraded SLS variants may encompass the VAB and other nearby buildings, including the press site. This could create quite a logistical challenge for NASA when it comes to directing employees, the press and the public to safe spots for launch viewing.)

The pad’s cavernous flame trench runs north-south through the center of the deck. Due to the space shuttle’s one-of-a-kind design, the orbiter’s main engines were offset from the vehicle’s dual solid rocket boosters. A triangle-shaped flame deflector sat beneath the shuttle to funnel main engine exhaust out the south side, and booster exhaust toward the north. For SLS, the core stage engines and boosters are aligned; all exhaust will billow north toward the coastline.

With the shuttle’s old service structures long gone, the bulk of the pad infrastructure includes three lightning protection masts and large posts on which the Mobile Launcher rests after the crawler brings it to the pad. (The crawler then leaves to go do "other things" again.) Three massive water pipes plug into the ML, which feed the platform’s sound suppression system from a nearby water tower. One pipe floods the rocket’s 10 by 20-meter exhaust port; the other two connect to large sprinklers dubbed "rain birds" that douse the ML deck as SLS lifts off. All of that water dampens sound waves from the engines, keeping the noise from damaging the vehicle as it lumbers toward the sky.

On the pad’s west side, there’s an elevator bank and stairs used to reach the ML deck. Ellis and I walk past a single parking space with red stencil letters that read: "RESERVED AMBULANCE ASTRO VAN." For the past three decades, this was the spot where astronauts stepped out of their iconic silver van before boarding space shuttles. It seems likely the same spot will be used for SLS and Orion. As I look over at the nearby elevators, it occurs to me that a group of astronauts might stand here one day enjoying a last breath of fresh air before embarking on a multi-year mission to Mars. I try to imagine the Mobile Launcher and a towering SLS straddling the flame trench, creaking and groaning from the pressure of supercooled liquid hydrogen and oxygen fuel tanks.

That day may not come for 20 years. Standing there, the prospect seems far-fetched yet plausible, leaving me both awestruck and unsettled. We drive down the pad ramp and head back toward the VAB. The empty launch pad recedes in my side mirror.

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth