A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 02, 2016

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Departs Spirit Mound, Embarks on Toughest Exit Ever

Sols 4541 - 4569

While Opportunity worked along Endeavour Crater's western rim through November, taking pictures, hiking slopes, and finishing work in the depths of Cape Tribulation, the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission scientists plotted a push to the gully, a trek that will challenge the robot field geologist as never before.

“Until we get to the top of the gully, it's all about getting to the gully,” MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, said as December peeked over the horizon. “The gully is the next big science priority on our list.”

It is also the centerpiece of the MER’s tenth mission extension science campaign. The gully is an ancient feature, believed to have formed some four billion years ago, around the time many planetary scientists believe Mars was more like Earth, with water in lakes, rivers, and even an ocean. The leading working hypotheses are that is was carved by water or a debris flow.

Whatever the rover and the scientists find, it will make history and inform textbooks on Mars. Research at this site will mark the first time any surface mission has studied a gully this old up close.

Although the traditional Thanksgiving break celebrated in the U.S. tempered work in November, Opportunity still managed to put in a productive month. The rover left Spirit Mound and then visited two more similar mounds, the first named Pompys Tower. After documenting Pompys Tower in pictures and skirting a potentially dangerous boulder field, the rover drove on to Elk Point, the third in the trio of mounds in the area and was finishing imaging there when the Sun set on the month.

“It's all been about traveling and wrapping up things in the lower section of Cape Tribulation,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL). “Now we’re getting back on the road again and anxious to get to the gully.”

It won't be easy. Although the feature is just 1 kilometer (0.621 miles) away by the planned route the rover will take, the driving in the Martian days or sols ahead will be arduous. Getting to the gully could take as long as six months.

The plan, according to Squyres, is for Opportunity to drive diagonally south/southwest, up the slopes of the rim and onto the flatter, plains terrain that surrounds Endeavour Crater. Then, the rover will head south toward the top of the gully. The going is already tough, and it will get tougher.

Getting back up the rim is going to take a lot of work. Actually, that might be an understatement. Opportunity will be doing more hiking than driving. In order to get back on the flatter plains where she can make the kind of progress she's used to, the robot first must climb up several hundred meters to the top of the rim. That will require carefully navigating her way on steep slopes, driving on angles that are at the recommended limits for a MER rover.

This first leg of the rover’s exit from the lower section of Cape Tribulation is going to be "pretty gnarly," said Squyres. "In terms of an extended stretch of challenging mobility," Squyres said, "this drive is the hardest thing Opportunity has ever attempted.”

The pot of science gold at the gully however makes this effort, the latest in Opportunity’s long line of incredible efforts, so worth it. From the sounds of the "push," it would almost take a Martian dinosaur bone, metaphorically speaking, to stop this self-imposed charge of the gully brigade.

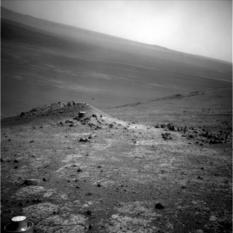

From Pompys Tower

Opportunity took this image with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) on Nov. 22, 2016 from a perch on the rocky slopes of Pompys Tower. Named for Pompeys Pillar in Montana, a site Lewis and Clark visited, the team chose the original Clark spelling, said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres. This view shows the rippled floor of Endeavour Crater and Spirit Mound in the distance. This image was processed by the Pancam team in false color, a technique that enables the scientists to better discern the different geology in the rusty redness of Mars.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

It is important to remember though that MER began as, and continues to be a discovery driven mission. "If we find something great along the way, we'll slam on the brakes and stop,” assured Squyres. "But it's time now to move on."

The MER team’s extended mission proposal focused on three primary science objectives: finding more Matijevic Formation, the most ancient Martian strata the mission discovered on Cape York at Matjevic Hill in 2012–2013; studying the gully top to bottom; and analyzing the bedrock inside Endeavour Crater to see how it differs from the same kind of bedrock found on the plains.

Opportunity drove into the extended mission in September when she departed Marathon Valley and headed for Spirit Mound to search for the ancient Matijevic Formation bedrock that has been elusive for the last four years. “This mound, we thought, was our best pre-gully chance to find more Matjevic Formation,” said Squyres. “That's why we went all the way down there. Having answered the question – it turns out it's not there – then the thing to do is boogie as fast as we can to the top of the gully."

As the rover begins the long and winding exit across slopes forming this section of Endeavour's western rim, the rover began deviating from the original extended mission route. "We will be deviating from it more," said Squyres.

In detailing the map that accompanied their extended mission proposal, the MER officials last year "drew some dots" on a traverse "as reference points to describe the landmarks that exist along the way," Squyres explained. "But do not make the mistake of thinking that we intend to stop and do science at each science waypoint. In fact, some of the waypoints don't have any particular significance and we're not going to visit at all," he added. "The only science waypoints that really matter are 1, Spirit Mound, and 13, the top of the gully.

Nearly 13 years into a mission that was originally slated for 90-days, Opportunity continues to amaze. Aside from a stuck "on" heater that forces her to shut down every night, a broken shoulder joint, a "frozen" actuator in her right front steering wheel, and the loss of her long-term or Flash memory, the rover has been performing "much the same as when we took her out of the box," said Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all of NASA's Mars rovers.

Fortunately, the Martian spring has not darkened Endeavour with a dust storm, not yet anyway. Even so, Opportunity is again being called upon to demonstrate her MER mettle in ways and over a span of time that would present a challenge to any Mars rover. In coming months, the robot will have to confirm her ability to climb and rove nearly sideways sol after sol on steep slopes like she did in Endurance and later, after a planet encircling dust storm, Victoria Crater. Perhaps too, she will rely on her robot DNA that somehow enabled her twin, Spirit, to scale record-setting heights on Husband Hill.

"The MER rovers are pretty good mountain goats when it comes down to it,” said Lead Flight Director Mike Seibert, also a rover planner (RP) at JPL. "We've pushed the rover pretty hard in the past few weeks. And we're going to keep pushing pretty hard as we continue to climb up the rim.”

The real challenge for this rover apparently lies with the terrain. "The high tilts and finding a pathway that is within the capability of the rover is somewhat of a worry," said Nelson. "But Opportunity has done pretty much everything we've asked. As long as we don't ask more than what she's capable of, we believe the rover will continue performing admirably."

Like always, Opportunity is doing the work, making the effort sol after sol after sol, chugging along in a very unforgiving environment. The science ahead, it seems, is screaming, and the parallels to old world scenarios playing out on Earth are uncanny.

The MER mission's research at the ancient gully will not only be the first study of such a Martian geological feature so rich with history, but Opportunity is the only rover or land-based 'bot that has access to the remnants of Mars' Noachian Period, the time when water was likely flowing in various ways and in numerous places on the Red Planet. If the rover and the scientists do find evidence that the gully was carved by water it would certainly bolster that long-held theory.

"If we show that this gully was carved by water, then that will tell us something about water on Mars a long time ago," said Squyres. "But we're not going to debate what formed this thing, we're just going to go and find out.”

The road ahead will be brutal. “It's rocky. It's steep. It's challenging. And we have a hugely important science objective out in front of us," Squyres summed up. "We're playing for pretty high stakes right now.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

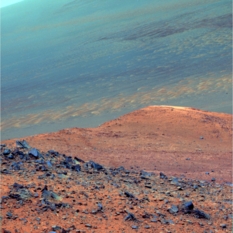

Top of the Tower

Opportunity took this image of the top of Pompys Tower with her Pancam, after she drove to the feature’s southwestern side on Nov. 17, 2016. The Pancam team processed it into the false color version shown above. “It’s another mound with a lot of rocks on it,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson. [See below for true Martian color version.]When November dawned at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was finishing up her work at Spirit Mound, the first major attraction and science waystation on MER's tenth mission extension.

The sky overhead was hazy, typical for a Martian spring, with the atmospheric opacity or Tau gauged to be 0.954, on the rover's Sol 4541 (November 1, 2016). With a still respectable solar array dust factor of 0.711, Opportunity was able to produce 390 watt-hours of solar power. Not great, but not awful. Her total odometry was 43.45 kilometers (26.998 miles).

The robot field geologist devoted the first five sols of the month taking Navigation Camera (Navcam) and Panoramic Camera (Pancam) images of the scene as far as she could see around Spirit Mound. As intriguing as some of the images are, they endorsed the scientists' earlier conclusion: the rover was not going to find any Matijevic Formation bedrock at this site.

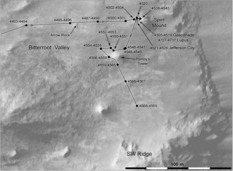

From Marathon Valley to the Gully

This map show the segment of Endeavour Crater's western rim that includes the Marathon Valley area that Opportunity investigated in 2015-16, and a fluid-carved gully that is the MER mission’s next major attraction destination to the south. North is up. The width of the area covered in the map is about 800 meters or about a half-mile. The rover entered Marathon Valley in July 2015. Tim Parker, of JPL, mapped the rover's traverse with a gold line onto an image from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Zoom in to view route.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

On Sol 4546 (November 6, 2016), Opportunity left Spirit Mound for good, driving about 34 meters (111.55 feet) to the south-southeast, heading for the second of three mounds on the itinerary, named Pompys Tower.

The team is continuing to name major targets and sites after places that Lewis and Clark visited during the Corps of Discovery Expedition in 1804-'06. So the second mound came to be Pompys Tower, named after Pompeys Pillar National Monument, a rock formation located in south central Montana where Clark inscribed his name in July 1806. At 51 acres (21 hectares) in size, it is one of the smallest National Monuments in the U.S.

With regard to the spelling herein of Pompys Tower, the name has appeared in several versions over the years, with and without an ‘e’ and with and without an apostrophe. The MER team doesn’t take target naming lightly, not often anyway. “It’s Pompys Tower,” Squyres wrote, confirming the spelling.

While the feature Lewis and Clark visited is called Pompeys Pillar today, Squyres pointed out that “in Clark's original journal recording the discovery, he wrote it Pompy rather than Pompey” … and “called it a Tower rather than a Pillar.” As for the spelling, ‘Pompy’ versus ‘Pompey,’ Squyres noted that Clark's spelling “tended toward the idiosyncratic.” In the same journal entry, Clark described the tower as “200 feet high and 400 paces in secumpherance.” As a result, “many people assume that the feature's name was misspelled, and that what Clark had in mind was Pompey's Pillar, a Roman column in Alexandria, Egypt,” Squyres explained. “Evidence suggests, though, that in fact it was more likely named after Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, Sacagawea's son, who Clark had nicknamed ‘Pomp.’”

Regarding the apostrophe, since it was originally written in Clark's journal and on the expedition map as ‘Pompys Tower,’ that is what the MER team chose to use, the original. “There's the added benefit that apostrophes are among the special characters that some of our software has trouble with,” said Squyres.”

So, following the drive to Pompys Tower on Mars, Opportunity collected the routine Navcam and Pancam panoramas so the rover planners could see the road ahead and the scientists could hunt for any new Martian oddities or treasures. And then, the rover concluded the first week of the month, on Sol 4547 (November 7, 2016), taking the frames needed for a full 360-degree Navcam panorama.

Opportunity was supposed to drive into the second week of the month and put, hopefully, at least another 12 meters (39.37 feet) behind her on Sol 4548 (November 8, 2016). Revved up, the rover began the grueling hike. Suddenly, after just 85 centimeters (33 inches) of progress, she stopped. The drive was terminated.

Ever since this freewheeling robot got stuck in Purgatory Dune back in April 2005 her flight software sports a special algorithm that automatically stops a drive any time three or more wheel motors are drawing higher than expected currents during a drive. While Opportunity eventually did unsnare herself, the algorithm was created as a specific safety-check and subsequently added to an upgraded version of the rover’s flight software, to prevent the potential for future embedding events. [Note: Geologically speaking, the "dune" into which the rover drove is technically a ripple, but the memo on the name change to Purgatory Ripple has not yet been released. "If you get stuck," noted Seibert, "it doesn't matter what you call it."]

This time however, Opportunity was driving up hill and not even near sandy soils. Terrain on Mars of course matters as much as anything to a rover. To the mission's good fortune, the Martian ground or terrain that the rover has been climbing and driving across on these rim slopes is about as good as the RPs could hope for.

"I consider it something equivalent to driving on the spray-on color coat that goes on a stucco wall," said Seibert. "It's got a lot of texture, and a lot of grip. We're not digging in at all and we're barely seeing wheel tracks most of the time."

That would indicate that three wheel motors were drawing higher than desired current, because of the steep terrain. The default 'stop' was, in effect, a false positive, but one without negative consequences.

"All six wheels were nicely on terrain,” confirmed Seibert. “Whenever we're trying to drive up hill, the right front wheel likes to draw more current. It’s been doing that since Victoria Crater and before, since the steering actuator stopped working. And when we're driving straight uphill, the back two wheels take most of the load, and so their current levels, as a result, are higher," he explained. As a result, the safety-check tripped and the rover stopped in her tracks.

Before Opportunity drove again, the engineers addressed the issue. “This safety-check is by default turned on, but we can send a very specific command to disable it,” said Seibert. “Disabling safety checks is not something we take lightly, but we became more cognizant since we started driving upslope that this safety-check might trip more frequently. And we began then, as necessary, disabling it, so we don't have it continuing to trip while the rover is climbing. If the terrain looks similar to what we've just driven over and we don't see any signs of wheel sinkage, we will disable that one safety-check and push upslope," he said. "But all other safety checks remain 'on.'"

Opportunity successfully completed the 4548 drive on Sol 4550 (November 10, 2016). Heading west or up slope, she drove about 12 meters (39.37 feet) around to face the northeastern side of Pompys Tower.

Pompeys Pillar, Earth

Located along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail in south central Montana near the Yellowstone River, Pompeys Pillar was proclaimed a national monument in January 2001. Prior to that, it was a national historic landmark, designated in 1965. Lewis and Clark first stopped there and camped in 1806. “Evidence suggests, though, that in fact it was more likely named after Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, Sacagawea's son, who Clark had nicknamed ‘Pomp,’” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres.Bob Wick, BLM

The rover was scheduled to drive again on Sol 4552 (November 12, 2016), after a turn in place from her position on the steep slope. As Opportunity began the sweep into the turn in place, once again she abruptly stopped. This time, it turned out that another safety-check in her protective software that stopped the drive because of elevated wheel currents in the problematic right front wheel, something familiar to the RPs.

“This event was very similar to what we saw over in Marathon Valley right after leaving the North Wall, over by where we were investigating those grooves that are carved down through the valley,” said Seibert. “We tried to do a big right turn and when we sweep the right front wheel downhill, since the steering actuator doesn't work anymore, occasionally the edge of the wheel catches the surface in a little crack or if it's just really textured surface, it can catch."

The stress and pressure to the outside of the wheel applied by the turn is increased as the wheel tries to maintain a constant speed during the turn. “So now it's got this friction force and it's kind of acting like a clutch, and also deflecting that front strut a little bit puts extra pressure on it, further exacerbating the problem," Seibert explained.

Two events in a row. Two different safety-checks. Annoying. But the MER team found no reason to panic. They'd seen it all before.

"Our limits are set really low, just to be really safe, and the safety-check tripped," said Seibert. "I would rather have the drive stop than keep going and potentially damage the motor. We were able to move on quickly from that.”

Opportunity recovered the drive on Sol 4554 (November 14, 2016), putting another 11.8 meters (38.71 feet) in the rear-view mirror. This time, the robot made a softer, gentler turn babying the right front wheel. "We headed due west and continued uphill to take more images, and that drive worked really well,” Seibert said.

Not surprisingly, Pompys Tower turned out to be much like Spirit Mound. "It was another mound with rocks on it," Arvidson described. "So we took images."

In some of those images and in the HiRISE overhead images the team was working with to guide Opportunity, the team caught glimpses of bumps in the Martian road ahead, a lot of bumps, as in a boulder field covering the steep slope and the rover's path onward.

History or graffiti?

Or both? During his return trip to St. Louis, William Clark of the Lewis & Clark Expedition climbed the Pillar and carved his signature and the date into the sandstone. In his journal, he wrote, that atop the sandstone feature he “had a most extensive view in every direction on the Northerly Side of the river.” He also noted: “I marked my name and the day of the month and year." Archeological evidence suggests that the big rock has been witness to 11,000 years of humanity passing through. In addition to Native American pictographs and the signature of Clark, hundreds of other people, including early pioneers, carved their initials into the rock. Clark’s inscription is the only remaining physical evidence visible on the Corp of Discovery’s trail.Bob Wick, BLM

"The HiRISE imaging looked like there was some pretty good-sized rocks and that it might not be passable,” said Seibert. “We were stuck with the choice of trying to go through a rock field upslope of the mound, or go through some very high tilts immediately down slope and skirt around to the east. We decided to scope out to the west to see if there was a path through the rock field.”

Meanwhile, the weather was getting slightly better. By mid-month, November 15, 2016, the sky overhead and the rover's power production had improved. Opportunity was producing 468 watt-hours with a slightly worse solar array dust factor of 0.697. The haze in the sky overhead dissipated a bit, with Tau down to 0.862. The rover's total odometry was 27.04 miles (43.51 kilometers).

On Sol 4556 (November 16, 2016), Opportunity drove slightly downhill, along the far eastern extent of the rock field at Pompys Tower, about 12.6 meters (about 41.34 feet), so the ops team members could see the extent of the rock field. "We wanted to see if there was terrain past it," said Seibert. “Lo and behold, there was a very nice, small channel between some of the larger rocks, a channel that runs, through the boulder field, along the north side of Pompys Tower, which is kind of rolling terrain,” he said.

The MER team discussed it. They could send Opportunity on this path straight through the boulder field, "but it would have been unpleasant and slow,” said Squyres. Ultimately, team members decided “the smart thing” was to skirt the rock field or more or less drive around it.

Opportunity set out again on Sol 4559 (November 19, 2016) and put another 10.68 meters in her rear-view mirror. “Instead of a straight line through the rock field, we drove across slope,” said Squyres. “We could pretty much pass mostly to the east of the rock field.”

“We went southeast on Sol 4556 and then continued southeast through the lower reaches of the boulder field on 4559," Seibert elaborated. “The rock field is not as dense after the 4559 drive and it looks like there is sparser rock coverage going towards the next mound, Elk Point.”

Following the usual post-drive images, Opportunity recharged. Then on Sol 4560 (November 20, 2016), she aimed her APXS to the sky and took an argon measurement for the mission long study on Mars' atmosphere.

As Americans turned their focus to turkey or tofurkie dinners, and fall fell over the northern hemisphere of North America, Opportunity worked up to and through the Thanksgiving holiday. For the most part, the robot conducted a science light campaign from Sols 4561 to 4565 (November 21-25, 2016) taking care of the usual rover engineering business and taking a lot of pictures, remote sensing as the scientists and engineers call it.

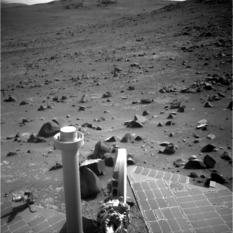

Pondering passage

Opportunity snapped this image, one is a series that the crew commanded her to take in order for them to see the extent of the boulder field, mostly to the right in this image. From all of the images the rover sent home, the team decided Opportunity could either take a tricky route through it or drive further east, skirt it, and then get back on the road west. The team chose to skirt it, making a fairly smooth pass more or less around the field to the left in this image.NASA / JPL-Caltech

On Sol 4566 (November 26, 2016), the rover took off, driving southeast for 17.33 meters. After a sol of more remote sensing or picture taking, Opportunity began another two-sol plan, “driving southerly,” as Arvidson put it, for 24.6 meters (about 80.71 feet) on Sol 4568 (November 28, 2016). The rover scooted through the lower reaches of the boulder field that the rover found above Pompys Tower.

“The rock covering is sparse enough here that it is not requiring complex routes through the field,” said Seibert. “We can drive over most of the rocks without issue, though we may slide slightly downslope.” At the end of the drive, Opportunity’s odometer read: 43,577.48 meters (44.577 kilometers, 27.077 miles).

Summer Solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars came and went that sol of 4568 or November 28th. On the next day, while the MER ops team planned the rover’s next drive, Opportunity rested and took images of her surroundings, focusing on the last in the trio of mounds, Elk Point. “We don't expect to see any actual elk, but that's what it's named,” said Squyres, deadpan. This site on Mars is named for the Lewis and Clark site, Elk Point, South Dakota, As history tells it, the Lewis & Clark Expedition made camp in or near Elk Point on August 22, 1804.

In reviewing the most recent images Opportunity had just sent home, it was easy to forget how exactly the rover captured these frames. "It was funny, we were planning the drive with the Navcams and looking at the drive path thinking: 'Gee, that looks really, really easy, what's the big deal here?'" mused Squyres.

"Then you remind yourself: 'Wait a minute, the rover was sitting on a 22-degree slope when it took this image,'" he continued. "The whole terrain you see is actually tilted to the left 22 degrees, because the rover was tilted by the same amount. It all looks flat if you don't project the images properly. But if you project them properly, you realize we're on a really steep slope. We’re almost 13 years in, and we're on this slope climbing," he marveled.

Martian bumps in the road

This image shows a sampling of the rocks and boulders that carpeted a field southeast of Pompys Tower. Opportunity used her Pancam to snap this picture on Nov. 19, 2016, the weekend before the rover’s crew took a Thanksgiving holiday break.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

As the robot documented the scene around Elk Point in pictures, the scientists were getting increasingly anxious to launch the gully brigade. “We are basically done with the lower part of Cape Tribulation," Arvidson said. "We went down to Spirit Mound and Pompys Tower to see if there is Matijevic Formation exposed, which there isn't. Now we want to get up-section. Now it's about getting up and out and looking at targets of opportunity as we go along.”

Those targets could be anything that catches the eyes of the scientists and truly piques their interests. 'Truly' being the operative word. “Just don't think we intend to do a traverse that goes from waypoint to waypoint to waypoint to waypoint," Squyres underscored. "We do not. We intend to do a traverse from Waypoint 1, Spirit Mound, to Waypoint 13, the top of the gully. Once we get back out onto the plains, it's should be faster, smooth sailing.”

Opportunity was slated to drive out of November and into December on Sol 4570. Despite the focus clearly being on the rover roving, the robot field geologist and her ground crew will certainly be on the lookout for more Matjevic bedrock and anything else that might be a total surprise and not anticipated. “You always want to do that," as Squyres put it. "But we're not going to follow the path that we put in the extended mission proposal. Right now, the marching orders we've taken on for ourselves is pretty simple: Get to the gully.”

Speed is the new mantra. Speed is of the essence. And as December fades in, Opportunity's story is all about mobility. "As a rover driver, I'm perfectly happy with that," said Seibert. "We like driving.”

So does Opportunity. The MER ‘bot long ago came to be known as the rover that loves to rove. But this departure is something different, even for this veteran. "Opportunity is doing remarkably well in navigating these high tilts," said Nelson. "Remember, we explored Marathon Valley, which slopes down into the crater, and then took a side exit into Bitterroot Valley and it too slopes down into the crater. The slopes get steeper as you move toward the crater, which is where we are now."

Oppy’s recent roves

This graphic charts Opportunity's recent rovings from Sol 4493 (Sep. 13, 2016), about nine sols or Martian days after the rover departed Marathon Valley en route to Spirit Mound to the most recent drive on Sol 4569 (Nov. 29-30, 2016), which took the rover to the northeast side of Pompys Tower. The annotated map is courtesy Phil Stooke, associate professor, University of Western Ontario, Canada, author of The International Atlas of Mars Exploration Vol. 2, Spirit to Curiosity: 2004 to 2014(Cambridge University Press, 2016). The base image was taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / P. Stooke

Opportunity is about as close to the interior of Endeavour Crater as she can safely be at this location, and still be able to get out. "We are now routinely running at tilts of 20 degrees," said Nelson. "And 20 degrees is getting close to the operating limits of rover. We try not to go beyond 25 degrees. If we lose traction, much like your car going up a really steep hill, our wheels will spin but it won't move the rover forward."

Although the terrain seems to be "fairly well compacted," said Nelson, "we have seen some reasonable slips in here. No high slips, but that will remain a potential issue and one we protect against. Right now, we're driving across slopes. That's helps."

Since the rover's wheels allow for a fair amount of slip, navigation can be a bit of an issue. The MER engineers and rover planners usually handle it with Visual Odometry, the process of determining the position and orientation of a robot by analyzing the associated camera images it takes and downlinks to its handlers. "It allows us to see where we are versus where we expect to be," said Nelson. From those images and analysis on the ground, the team then makes adjustments to the rover's position accordingly.

So far, Opportunity seems to be handling the intense driving in fine form. Other than her well-worn injuries and losses, all systems and instruments on the rover are "looking healthy and behaving as has been normal for the past 1000 or so sols,” Seibert reported. “We're not seeing any degradation in any system, so we're just going to continue to hike up the rim. It's kind of like the Cog Railway on Pike's Peak almost, the way the rover's cleats will dig into the terrain to get us up. This rover just keeps chugging along.”

Still, the next several hundreds of meters of driving will challenge Opportunity in new ways. "This rover has done little stretches of difficult driving in the past, coming out of Victoria Crater, for one,” said Squyres. “But this will be the longest, extended stretch of difficult driving that Opportunity has ever done."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Pompys Tower in Martian color

This is the near true Martian color version of the image of the top of Pompys Tower. It is dramatically different from the false color version. And it is Mars. It isn’t called the Red Planet for nothing. Everything on Mars, almost, is this color of rusty red.The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth