Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Begins Reconnaissance of Matijevic Hill

Sols 3089 - 3118

Written by

A.J.S. Rayl

Contributing Editor, The Planetary Society

November 6, 2012

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

After spending much of October driving around and taking pictures on Matijevic Hill, Opportunity hunkered down for Halloween and spent the holiday quietly, staying out of mischief's way and the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission roved another month closer to its ninth anniversary of working on the surface of the Red Planet.

As November 2012 blows in, Opportunity is in the midst of a reconnaissance of the hill to determine where she will settle in during the next several months to conduct the intensive science. "We're doing the walk-around," said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University. "We're doing a loop around Matijevic Hill, just like anyone would on arriving at a new at any geologic site. The first thing you do is walk around, take your pictures, see what's there."

A rise on the rim of the crater that overlooks Endeavour's bowl, Matijevic Hill is named for Jake Matijevic, the systems engineer who was active in Spirit and Opportunity's development and who led the engineering team for MER for eight years before and after their landings. He'd moved onto to the Mars Science Laboratory mission and, although he always seemed to still know everything about the MERs, he was Curiosity's Chief Engineer of Engineering Operations when he passed away unexpectedly last August. [See MER Update for August 2012, Sols 3029 - 3058.]

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / UA / S. Atkinson

On the loop around Matijevic Hill

After completing a first study of Whitewater Lake in early October, Opportunity hit the road, driving up Matijevic Hill and onto a north-west-south-east loop to conduct a geologic survey of the rise along the inboard side of the Cape York segment of Endeavour's rim. Named for rover pioneer engineer Jake Matijevic, the hill appears to be harboring hydrated rocks and clay minerals, according to orbital data collected with the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM),visible-infrared spectrometer aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that is designed to search for mineralogic evidence of past and present water. For more of Atkinson's work, please see his Road to Endeavour blog.Squyres and the team wanted to honor Matijevic and they wanted it to be some place really special, some place commensurate with his contribution, although there really is no way to measure what Jake did for these rovers. Nevertheless, so many times on this mission the stars seem to align, and apparently they did again. Even as the news of Jake's passing was circulating, Opportunity had gone off its southward course and was heading west, roughly toward the base of that special place, lured by a wild-looking, finned outcrop the team nicknamed Kirkwood.

Following an up-close look at Kirkwood in September, the robot field geologist maneuvered its way up and behind the oucrop to a flatter, light-toned, slab of rock called Whitewater Lake, which is marked with splotches of a darker overcoat or rind. As October began, Opportunity was homing in on one of those splotches to get a closer look at that dark coating.

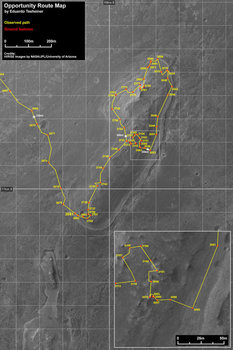

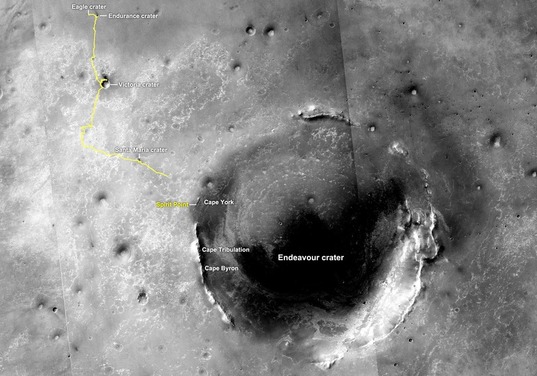

Opportunity route map

This route map shows Opportunity's travels up to its Sol 3114 (October 27, 2012), and the rover's approximate current location on Matijevic Hill, a rise on the inboard side of the Cape York segment of Endeavour Crater's western rim. This image was produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, who created it from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. As this map shows, Opportunity made some tracks around Matijevic Hill in October, the rover's Sols 3089 to 3118.NASA / JPL / UA / MSSS / E.Tesheiner

"When we got to Kirkwood and Whitewater Lake, we took our first taste of what seemed to be the two obvious main rock types that were present, to get a sense of what we're dealing with," said Squyres. "But rather than trying to tackle the nearest interesting looking problem in-depth, we wanted to get the big picture first," he explained. "It's just a sensible way of doing of geology. So we started at Whitewater Lake and we're going to finish at Whitewater Lake, and we will see what we see," he said.

By then though they knew the hill was about as special a place as Opportunity would ever visit and so in September it became Matijevic Hill.

Overlooking the 22-kilometer (14-mile) diameter Endeavour, it certainly offers a pretty cool view. More than that, the area is scientifically rich, one of the places on the big crater's rim where orbital instruments have detected the presence of clay minerals, a sign of the past presence of water and, notably, an environment more conducive to the formation of life than any previous past environment this rover has found.

After finishing it study of Whitewater Lake, Opportunity shifted into recon-mode, embarking on the Matijevic Hill Survey in mid-October. Taking a counterclockwise route from Whitewater Lake, the rover headed out on a north/west/south/east loop around the hill with plans to document its path and just about everything interesting in it and around it in pictures.

Little mounds dotting Matijevic Hill present a distinctive landscape and an ideal course for Opportunity. During the last couple of weeks, the rover has been driving short jaunts of 10 to 30 meters or so in its survey trek around the loop, hopping from mound to mound or outcrop. These geologic formations that now have names like Broken Arrow, Big Nickel, Coleman, Barnet, Fraser, Stobie, and Garson, are subbing as makeshift Martian rest stops.

The MER team, keeping to its tradition of initiating a new naming theme at every new rover site, decided to christen everything in the Matijevic Hill area for sites and formations in and around the Sudbury Basin. Located on the Canadian Shield in the city of Greater Sudbury Ontario, Canada, "The Valley," as locals call it, is one of the oldest impact craters on Earth. And, at 62 kilometers (39 miles) long and 30 kilometers (19 miles) wide, it is the second-largest known impact crater on Earth, after the 300-kilometer (190-mile) diameter Vredefort Crater in South Africa.

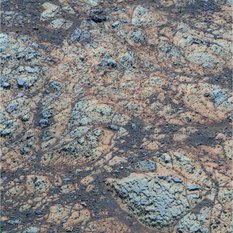

More newberries

Opportunity saw an untold number of the new kind of spherules or "newberries" again this month as she conducted her survey around Matijevic Hill. The rover took this image, produced here in false color by the Pancam team, as she was roving up the hill. Unlike the "blueberry" spherules the rover found previously in the mission, these "berries" are not made of hematite and are much more resistant than the "blueberries." The MER scientists are still analyzing the data and have yet to officially announce where they came from and how they think they formed.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

On Mars, Endeavour is only 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter, but it's the largest crater Opportunity will investigate, so istrange as some of the names may seem, the theme seems apropos enough, as naming themes go.

Once Opportunity began its survey of Matijevic Hill, it roved naturally into a routine. "It drives up to a spot and takes a full 360-degree panorama with the navigation camera, and then on the next plan [sol or day] it takes some panoramic camera (Pancam) images of the next spot before we drive on," explained Ed Guinness, MER scientist, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL), who's been taking Ray Arvidson's slots as science team ops lead this month, as Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, also of WUSTL, works with Curiosity. "We're pretty much in that pattern," Guinness said, estimating that the rover will travel a total of "about 300 to 400 meters" (0.81 to 0.24 mile) of distance around the whole loop.

"When we're done, we'll have this very extensive, very complete dataset of this whole area from which to pick out the high value targets to then examine in more detail later on," added John Callas, MER project manager, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where all the American Mars rovers have been created. "That's when we'll sit down with everything in front of us and figure out what we're going to do next," said Squyres.

The 10 short drives Opportunity pulled off in the latter half of October proved to be textbook. Beyond putting another 214.9 meters (702.72 feet) on her rocker bogie, they took the rover about halfway through the Matijevic Hill loop, reported Bill Nelson, of JPL, chief of the rover engineering team. "Despite her age, Opportunity is doing very, very well," he said.

The hope when Opportunity began the Matijevic Hill loop was that it would complete the survey in six weeks. Even after all these years, this rover still aims to please. "We have been driving at every chance and we're ahead of our schedule by a little bit right now," Callas informed. That means the rover should easily complete the loop before the end of November.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Corenll / ASU

Frood for thought

Opportunity took this picture of Frood, a small rock at the foot of an outcrop the team calls Garson, with her Pancam during the last week of October. It was processed here in false color by the Pancam team to emphasize differences in visual color. Since the rover began heading west on its north-west-south-east loop around Matijevic Hill, it seems to have crossed a boundary back into the geology of Shoemaker Ridge, where the first rocks the rover studied are located.Since the MER team has been fully incorporating orbital data from the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) into its planning, there's a lot less mystery involved in choosing the rover routes. "HiRISE imagery is an integral part of the planning now, both scientifically in terms of mapping out strategic plans for where we want to go, and tactically," Guinness said. "When we get the pictures from Opportunity's drive, we locate ourselves very precisely on the HiRISE imagery, and then, combining the rover and the HiRISE data, the rover planners pick out the path to the next destination."

Mystery still abounds however in the weird Martian formations and rocks that Opportunity has been seeing along the way, from the tiny but very different, tough little spherules or newberries reported in last month's MER Update to the mounds that decorate Matijevic Hill. Every target worth investigating here plays into some aspect of the timeline of events that occurred at Endeavour Crater, dating all the way back to the Noachian Era. All the MER scientists have to do is choose which pieces of evidence to study and then put the puzzles together. A simple goal difficultly reached.

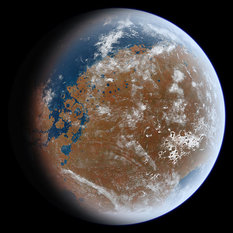

Noachian Mars?

This is an artist's impression of an early warm and wet Mars. Late Hesperian features (outflow channels) are shown, so this is not an exact impression of Noachian Mars, but the overall appearance of the planet from space may have been similar to the impression and to Earth. In particular, note the presence of a large ocean in the northern hemisphere (upper left) and a sea covering Hellas Planitia (lower right). The artist, Ittiz, created this image using knowledge of Martian geologic history and data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) an instrument on the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS). NASA officially ended the MGS mission in January 2007.Ittiz

Noachian Mars - which lasted from the planet's beginning, about 4.5 billion years ago, to about 3.5 billion years ago - was a different place than the Mars of today. Most planetary scientists generally believe it was warmer and wetter. Certainly, Mars' dried up river valleys and deltas, among other geologic features, suggest that. Proving it became NASA's overarching exploration objective on Mars. Follow the water became the mantra, and so finding evidence for past water was the primary science objective for the MERs.

When Opportunity roved across an ancient salty seabed before its primary, 90-day mission was over, back in 2004, it delivered that evidence. But now there's even better evidence in the form of clay minerals somewhere right around it, according to data collected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible-infrared spectrometer onboard MRO. A ground-truth finding of clay minerals - a class minerals known to geologists as phyllosilicates - would be a glorious scientific feather for the rover's mast.

At this point however, Opportunity is not stopping to smell the roses, not any of them. "The in-depth stuff is going to wait until after we've done this loop," Squyres said. "With Kirkwood and Whitewater Lake, we got a really quick first reconnaissance. We'll be done with the loop in probably another three weeks, and then we'll decide what to do next. It's still recon time right now."

Up on Mars, spring is transitioning to summer in the southern hemisphere of the planet where Opportunity is located and the weather has been good for motoring. The haze in the skies over Endeavour Crater fluctuated throughout October, a lot like smoggy summer days in Beijing, but the rover maintained the capacity to consistently produce more than half its full-power capability, and has had plenty enough power to do everything it's being asked to do.

"Opportunity is in great shape," said Squyres. "This loop is going really, really well. It's been a great success actually. We're seeing lots of stuff. We're getting all the data we came for and the team is working really well. Everything is just as smooth as it can be."

The veteran rover is still primarily driving backwards with its arm [instrument deployment device] partially unstowed, in the fishing position, "like a fishing pole with the end of the arm hanging straight down vertically," as Callas put it. The two broken mineral detecting instruments are still broken, "otherwise everything else is in really good shape," he said. "This is a rover with 35 kilometers on its odometry and the wheels have been well behaved. It's sounding a little boring, but all things really are working well," he confirmed.

For now, as Opportunity continues the Matijevic Hill Survey, the team members are more in a collection phase than an analytical phase. There was no new news on the spherules or newberries or anything else the rover has seen in October, and no scientific announcement is likely to come in the immediate future.

Opportunity is returning data daily and the MER team members, many of who are doing double-duty and working on Curiosity, have had their hands full and their minds occupied on whatever is happening in the immediate moment. Beyond that, deciphering and interpreting all the evidence coming down takes time and a good amount of thoughtful thinking and comparative analysis. "This requires a lot of patience," reminded Squyres. "Like I said before, we're going to be here, at Matijevic Hill, for months."

With Curiosity on the other side of the planet getting into all sorts of shiny and smelly things, patience is difficult for those who follow MER. Opportunity is carrying on roving to its 9th anniversary - a truly remarkable achievement in and of itself - with virtually no recognition.

Mars rover family portrait

This portrait shows the three generations of NASA's Mars rovers, all of which were designed, built, and managed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena / La Canada-Flintridge, California. the microwave oven-sized Sojourner from the 1997 Pathfinder mission appears in the lower left iforground. The Mars Exploration Rover model – Spirit and Opportunity – about the size of a golf cart is up and to the left moving counterclockwise. The Mars Science Laboratory / Curiosity, which just landed in Gale Crater last August, is hard to miss on the right. It's the largest and most heavily equipped model to date, and is about the size of a VW bug.NASA / JPL-Caltech

Those on the MER team, however, are keenly aware of the grander objective in Mars exploration and are secure in the mission's achievements and its place in history. "We're not alone in this," Callas said. "This is an adventure that's moving forward with more capability. Curiosity is the continuation of the uninterrupted surface exploration of Mars that began when Spirit touched down. We also know that Curiosity has a long way to go to catch up with Opportunity's record of achievements," he added. "It's not just the odometry and years, but the kinds of discoveries."

The end goal - to understand Mars - is the common denominator. It's what binds the rovers and the rover teams together. The reality is that what Spirit and Opportunity have discovered helps inform Curiosity, while the discoveries that Curiosity will make at Gale Crater, in turn, will perhaps add to the story Opportunity is writing at Meridiani Planum and maybe even the story Spirit uncovered at Gusev Crater. "It really is a win-win," said Callas. "And, we kind of like having company on the surface of Mars."

Behind the scenes, Opportunity - despite her jammed right front wheel actuator, her broken shoulder, broken heater and two broken instruments - is still every bit a shining robot star. "We do have a lot of MER veterans on Curiosity who like to come back do some shifts on MER, in part because of the familiarity and comfort level," said Callas. But likely a bigger part of it is the fun factor.

"Maybe you have this brand new Lexus with all the gadgetry and stuff in the driveway," Callas mused, beginning one of his analogies.

Ahh yes, but in the garage there's a classic '64 Mustang or '67 Camaro.

"There are times you want to take that classic out driving," Callas continued, "because it's just such a fun car."

An appropriate analogy for Opportunity, the "glamour girl," as Jake Matijevic defined the robot field geologist years ago . . . "a good girl" robot but one that nonetheless "likes to have fun." As for the team members, going to work everyday to drive or direct a rover on Mars is never not fun.

"But sometimes it's extra fun," Squyres noted. "And right now, it's extra fun."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

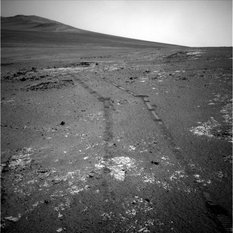

As September turned to October at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was conducting a science campaign at the base of Matijevic Hill, along the inboard edge of Cape York on the rim of Endeavour Crater. It had moved just a few meters above and behind the finned outcrop Kirkwood to take a look at Whitewater Lake, a large, light-toned block of exposed outcrop that had a darker coating or rind splotched on parts of it.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell Univ./Arizona State Univ.

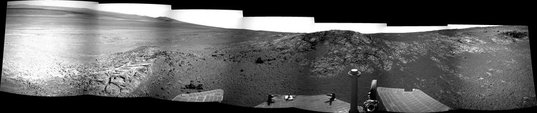

A view of Matijevic Hill 3D

On the horizon in the right half of this panoramic view is Matijevic Hill, named in commemoration of Jake Matijevic, (1947-2012), a JPL pioneer in creating robots to rove on Mars. The view appears in three dimensions when viewed through blue-red glasses (red lens on the left). Opportunity snapped the images that are combined into this view with the navigation camera on her Sol 3054 (Aug. 26, 2012), just a couple of weeks after she pulled up to the western rim area of Endeavour Crater. The left side of the panorama shows portions of the rim farther south.The rover had crossed into "the sweet spot," as Arvidson described it, where CRISM detected clay minerals in the form of smectite. And Pancam imagery that she had previously taken indicated there is likely mineral hydration in Whitewater Lake, so the rover spent the latter half of September checking it out up close, brushing off its surface accumulation of dust, and even drilling into it.

After grinding into Whitewater Lake, Opportunity repositioned herself to reach some of the dark coating and then took a full 13 filter Pancam image of it. "It was definitely different from Kirkwood and Azilda [the target spot on Kirkwood]," said Guinness. "Texturally, the rock was very fine-grained and the color was different. So we did IDD work there on a couple of spots."

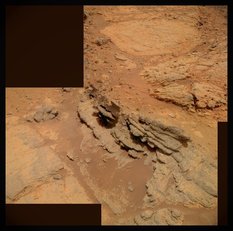

Kirkwood and Whitewater Lake

Opportunity took the images for this photograph as she began her investigation of Kirkwood and Whitewater Lake in September. In the middle of the picture, you can see part of the layered, sinuous-shaped Kirkwood outcrop. Just behind it, in the top part of the image is the lighter-toned, circular, "slabby" flatter rock called Whitewater Lake, which Ray Arvidson, the MER deputy principal investigator, believes may be a bearer of the clay minerals detected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Opportunity moved for perhaps the shortest distance it's ever moved on Sol 3092 (October 4, 2012), with less than 1 centimeter (less than a quarter of an inch) of total motion in order to position her arm on a dark-rind surface target, dubbed Chelmsford. Two sols later, 3094 (October 6, 2012), the robot field geologist brushed Chelmsford with the rock abrasion tool (RAT) for 15 minutes. "We then took the usual microscopic imager (MI) pictures and followed it with the APXS," said Guinness.

The dark covering did feature some chemical differences according to the data collected by the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS). "Compared to Kirkwood and Azilda, it had more calcium and manganese this was after brushing away the soil and dust cover," said Guinness. "It was also higher in sulfur and chlorine."

"We did get some interesting elemental chemistry on it, but it's not dramatically different from the underlying stuff," said Squyres, hedging on what it may mean. "It was fairly subtle. We're still doing the analyses on it, but we got our first taste and so we kind of know what we're dealing with there."

As for the hydrated minerals that Pancam saw lurking in Whitewater Lake?

"We have hits from the so-called hydration index that we see with Pancam that some of these outcrops might have some water in them," Squyres said. "We can investigate that further with the APXS looking for excess light elements, but we have a lot more work on that," he said.

As the second week of October took hold, Opportunity moved her arm slightly, to Chelmsford-2 and performed another RAT brush of the surface on Sol 3096 (October 8, 2012), then followed it with the usual MI mosaic and placement of the mineral-analyzing APXS. And with that, the Whitewater Lake investigation was done, at least for the time being, and Opportunity was ready to rove.

Brushing Chelmsford

Opportunity spent the first part of October checking out the dark rind or coating that covers parts of Whitewater Lake at the foot of Matijevic Hill. The rover used her rock abrasion tool (RAT) to brush two target locations that the team dubbed Chelmsford-1 and Chelmsford-2. Those two brushed targets are the two dark circles shown here in the center of this raw image, which the rover took with her panoramic camera (Pancam).NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

On Sol 3098 (October 10, 2012), the robot field geologist began the loop around Matijevic Hill to survey the area where the clay minerals seem to be hiding. "It's what you'd do if you were a geologist and were there," said Squyres. "You just helicoptered into a brand new site you'd never seen before and you've got some time to work things out, so the first thing to do is get your photos, then walk the outcrop and find out what's there, survey the whole thing generally so you can formulate an intelligent plan for how to investigate it in detail. Opportunity is doing just that, taking a counterclockwise loop around the hill that started at Whitewater Lake and is going to finish at Whitewater Lake."

Turns out a number of small mound features, as well as outcrops on Matijevic Hill are conveniently positioned to serve as rest stops for Opportunity as she journeys around the loop and one of them was her first destination. "After Whitewater, on Sol 3098 (October 10, 2012), the rover drove 17.93 meters (58.82 feet) to a mound that was later called Broken Hammer, and imaged it from three sides," said Nelson. Then the next sol, 3099 (October 11, 2012), the rover collected an atmospheric argon measurement with her APXS and took care of other routine business.

Opportunity closed out the second week of the month with a 20.44-meter (67.06-foot) drive on Sol 3101 (October 14, 2012) that put her at Big Nickel. There, the robot field geologist took pictures of boxwork and possible veins in light-toned bedrock below the mound.

From Big Nickel, the rover drove on, heading northwest. She put 13.02 meters (42.72 feet) on her rocker bogie on 3103 (October 16, 2012) before she stopped at Coleman. This mound appears to be exposed by a small crater downslope, and the MER scientists noted boxwork again.

Boxwork is a fairly uncommon type of mineral structure on Earth and one that is interesting to see on Mars. On Earth, boxwork is typically formed by erosion rather than accretion and is found in caves and erosive environments. It is usually composed of thin blades of the mineral calcite that project from cave walls or ceilings and intersect one another at various angles to form a box or honeycomb or pattern.

The names for these mounds and outcrops and slabs of rock in and around the Matijevic Hill site are taken from places in the Sudbury Basin in Ontario, Canada, as Arvidson mentioned in the previous MER Update, a basin formed as an impact from a bolide approximately 10-15 kilometers (6.2-9.3 miles) in diameter that occurred 1.85 billion years ago in the Paleoproterozoic era. With an impact as large as this estimate, debris probably scattered around the world, but much of it has since been eroded away, according to models. As recently as 2007 though, rock fragments representing a layer of iron-rich rock ejected by the Sudbury blazing meteorite event, were found at Gunflint Lake, Minnesota, nearly 500 miles from the impact site.

Scientists believe the present size of the Sudbury Basin is actually a smaller portion of a 250-kilometer (155.34-mile) round crater that the bolide originally created, and that subsequent geological processes deformed it and transformed it into the current smaller oval shape. On Mars, the MER scientists hope to learn more about Endeavour Crater and what has transformed it over the millennia.

On Sol 3104 (October 17, 2012), Opportunity drove another 19.13 meters (62.76 feet) to Barnet, where she took pictures, capturing another outcrop in the background nicknamed Fraser in the process. All told, the rover had driven some 70 meters (about 230 feet) in those first five drives away from Whitewater Lake.

"The drive from Big Nickel to Coleman to Barnet was all kind of northwest," Nelson pointed out. "Each drive was preceded by targeted imagery and followed by 360-degree navigation camera (Navcam) panoramas," added Callas.

During the third week of October, Opportunity zipped through two more jaunts on the loop around Matijevic Hill. On Sol 3105 (October 18, 2012), she headed west for 18.52 meters to face Stobie, with Totten in the background to the north. From there, the rover headed southwest for 15.01 meters to Garson [aka Station 5] on Sol 3107 (October 20, 2012). On the following sol, she tended to routine tasks.

"The mounds are pretty striking, but I don't know what to make of them," said Squyres. "They clearly seem to be made up of a more resistant material. From the one that I've seen, they look like they're fairly rich in the little spherules [newberries], which tend to be fairly resistant. More than that, I can't tell you. We're still working that out."

As part of a mission-long study, Opportunity took an atmospheric argon measurement with her APXS on Sol 3109 (October 22, 2012), and then took off again. She logged 35.47 meters (116.37 feet) on Sol 3110 (October 23, 2012), and stopped at Station 7, where she took a bunch of pictures of targets . . . Frood, a little rock at the foot of Garson . . . Podolsky, an area on other side of Garson . . . and Strathcona, a small mound not too far from Garson.

On 3112 (October 25, 2012), the robot field geologist took two Pancam mosaics of the area surrounding Station 8 from her position at Station 7, and then drove 29.96 meters (98.29 feet) to Station 8. There, the rover took pictures of some platey outcrop lying around in the general vicinity, two of which garnered the names MacLennan and McConnell.

Opportunity revved up again on Sol 3114 (October 27, 2012) and drove 9.00 meters from Station 8 to Station 6. "We had never been to Station 6 before," noted Nelson. She took the images for a mosaic of McCready, a cobbley-looking outcrop there, and McKim, a thinnish line of outcrop, notable for what appears to be a sizable fracture.

The MER science team members continued to see veins here and there in the images of bedrock the rover sent home this past month, all of which, ostensibly, are fractures that have been filled with minerals from flowing water. "There were some on Kirkwood and we took Pancam images of them, but we didn't really get a good look, because they were kind of small and difficult to get any real details on," Guinness noted. "Whitewater, being on the rim of a crater, was clearly fractured and minerals were deposited in these fractures. But we haven't found a fracture and vein filling large enough yet that we could put our instruments, but as we [tour] this hillside here, we're still on the lookout for that."

On Tuesday, the rover's Sol 3117, Opportunity drove for the last time in October, putting 33.02 meters (108.33 feet) more on her odometer, reported Nelson. She first angled uphill to the northwest "to get a few close-up images of outcrop," said Guinness, who was the Science Operations Working Group (SOWG) chair on Monday, October 29th, the day the plan was uplinked to the rover. Then, the robot field geologist headed south for about 15 meters, he said, continuing the loop around Matijevic Hill.

Endeavour Crater orbital view

This image of Endeavour Crater was taken by the Malin Sapce Science Systems' Context Camera, which is onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The yellow line on this map shows the route Opportunity took from Eagle Crater, where the robot field geologist landed in January 2004 (at the upper left end of the track) to a point about 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) away from the rim of Endeavour Crater. The rover arrived at the 22-kilometer (14-mile) diameter hole in the ground in August 2011, after a three-year journey from Victoria Crater. The rover entered by way of Spirit Point, an area named after her twin "sister," which stopped communicating in March 2010.NASA /JPL-Caltech / MSSS

As Opportunity stopped to chill and take more pictures on Halloween, Nelson calculated her mileage for October. She began the month at 1 a.m., local Mars time, on Sol 3089 with 35,047.47 meters (35.04 kilometers, 21.77 miles) on her odometer. At the end of the drive Tuesday, her odometer read: 35,261.66 meters (35.26 kilometers, 21.91 miles). "Delta is 214.19 meters," he reported. Or 702.72 feet.

All in all, "consistent" seems to be the descriptor word for Opportunity during the past four weeks. Throughout October, the rover was, as the Star Trek adage puts it, "steady as she goes," dutifully pressing onward drive after drive after drive. "Because of Mars time, we're restricted and can't drive every day." said Callas, "but the rover has been keeping a pace of driving at every chance it can."

The two rock faces of Matijevic Hill

These two pictures show the two different rock types Opportunity has been roving across during the rover's investigation of Matijevic Hill. The image above shows the dark, spheruled bedrock that the rover is seeing again near the top of Matijevic Hill. The image below the sort of circular Whitewater Lake, the flatter, light-toned rock type that the robot field geologist spent a couple of weeks checking out in late September, early November.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

The skies over Endeavour have been hazy, and the rover reported opacity or Tau as fluctuating from 0.604 to 0.722. While Opportunity's solar array dust factor bounced from around 0.657 at the top of the month to 0.619 near the end, the rover was easily producing enough power to keep levels between 531 watt-hours and 579 watt-hours, ample energy for this robot field geologist to carry out her assigned tasks.

Opportunity continues to rove mostly backwards, but she has been driving forward "if it makes sense," said Callas. "You may recall the right front steering actuator jammed years ago, so it's not as convenient to do tight turns in a particular direction with that steering actuator jam," he explained. "So sometimes we drive forward to minimize the amount of turning we have to do, and that minimizes the stress on the mobility system."

Remarkably, there has been no further issue with the "hot" right front wheel drawing more current than the other five wheels. "That right front wheel is well behaved," confirmed Callas. "Occasionally the energy draw is elevated compared to the other wheels, but we have not seen the huge excursions in wheel currents that worried us some years ago when we were mostly driving forward. Driving backwards seems to mitigate most of that."

As Opportunity has made her way west and now as she begins to head south on her loop around Matijevic Hill, she is roving back into familiar geology. "We started midway up the hill on Whitewater and drove north for 40 to 50 meters (131.23 to 164.04 feet) and were seeing fine-grained, light-toned outcrops [like Whitewater Lake] with possible veins embedded in the rocks," recounted Guinness. "Then we turned to the west and headed up Matijevic Hill and about halfway up we started seeing rocks that look familiar to those we saw when we first drove onto Cape York, like Chester Lake, the rock that had lots of embedded coarse-grained glass in it."

Opportunity is also seeing plenty of those mystery spherules or newberries - on which there was no new science news in October. There is, the scientists say, still much work to be done on that investigation. "It's not clear if the composition of Kirkwood is the same throughout and the spherules are the same composition as the matrix they are embedded in, or whether there's a compositional difference," noted Guinness.

"When we brushed it, we didn't see a difference," Guinness continued. "We need to find a similar outcrop where we could do a number of different spots and see as we move on different spots - assuming the proportion of spherules to matrix varies in those different spots - how the different elements change with that variation, and the abundance of the two components. That would help us figure out if the spherules and matrix are really the same composition or whether they are two different materials. That's work still to be done," he said.

Chester Lake

Chester Lake was the second rock on the rim of Endeavour crater that Opportunity moved in on for close inspection. The rock is about 3 feet (1 meter) across and lies on the inboard (southeastern) side of Cape York, which forms a portion of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. Rover team scientists chose it for inspection because it is in-place bedrock that appears to be representative of a region of outcrops on the inboard side of Cape York. It appears to be breccia, a type of rock composed of fragments of older rocks fused together.NASA / JPL / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

But there are hypotheses and notions of how the spherules got there. Arvidson, who's been studying Martian geology since Viking, is leaning toward the theory that contends they formed by an impact and are ejecta deposits. "One idea is that we have been traveling across an impactite and it represents the really hot ejecta that was dumped down sometime in the Noachian," he said. "These deposits may or may not have been caused by whatever created Endeavour," he said.

"You do see [such] spherules in volcanic eruptions, in rhyolites in particular, very explosive volcanic eruptions that make ash deposits," Arvidson pointed out. "And you can imagine a huge explosion associated with an impact and a lot of material, and basically melt and vapor that are being transported outward accumulates in these spherules and drops down."

Extrapolating along the impactite theory lines, how would the impact have created clay minerals?

"It would have been an impact into a crust that would have had water in it and that would have produced an enormous amount of heat and steam that could have instantly altered the some ejecta to clay," Arvidson suggested. "In addition, with those really hot conditions there would be extensive hot water moving through the system conditions may have been right for clay mineral formation."

But, Arvidson cautioned: "We really don't know. I'm purely speculating here. This is just my preferred hypothesis. There's not a team position yet," he underscored. "But the more I look at it," he added, "the more I think it's an impactite and ejecta deposit."

Smectite soil on Earth

Opportunity will soon be on the hunt for smectite on Matijevic Hill and the story behind how it formed. One theory is that it is the end result of an impact that produced an enormous amount of heat and steam, which then transformed some of the ejecta to clay. Time and more investigation will tell. Meanwhile, this is a close up image of the crinkly, cracked surface typical of a soil rich in smectite clay on Earth.University of Pittsburgh / Norris W. Jones

"You gotta be patient with us here," said Squyres. "The only time we've looked at these spherules carefully was at Kirkwood. Right now we're mapping. We're doing a survey of the outcrop to find out what's where and to enable us to formulate a plan. We're going to check out all this stuff in more detail but we want to do it in the most sensible way possible."

At this juncture, Opportunity has completed the northern part of the loop and is currently heading south to complete the other half, said Squyres. "We started at the 3 o'clock, if you will, then went to the 12 o'clock position, and now we're at the 9 o'clock position. We're about halfway around. Once we finish, then we will gather all the data together and see what we've got in front of us." He estimated that the rover has about three weeks to go on the survey.

The scientific challenge for the MER team is to sort out the different geology, terrains, and past environments at Endeavour Crater. "We continue to see the light-toned stuff that we think is represented by Whitewater Lake and we continue to see darker stuff that appears to be rich in these little spherules," said Squyres.

Opportunity's current location is pretty close to a place the rover was an Earth year ago as she was heading north of the western side, the other side of the rim at Cape York. "As we have worked our way west, it looks like we have crossed the boundary into more familiar Shoemaker Formation ejecta and we expect as we come back around that we're going to cross that boundary again and be back into this younger or older - I don't which it is - layered stuff, the Whitewater Lake stuff," said Squyres. "We will work it all out. Right now we're just making the basic map that we will use to formulate the plan to answer the questions you're asking."

When the MER team completes its work at Matijevic Hill, the mission's long-term goal remains the same - to head south to Cape Tribulation. "But we're going to be at Matijevic Hill for months," Squyres reiterated. "We are a long way from departing for Cape Tribulation."

In the meantime, Opportunity has her work cut out for her robot self and life will be anything but boring in coming sols. "I think things will become challenging once we're done with the loop, because then we'll have to formulate a plan," said Squyres. "And that's going to be fun."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / UA / S. Atkinson

An opportunistic view of Endeavour

This dreamy image, artistically processed by Stuart Atkinson of UnmannedSpaceFlight.com, offers Opportunity's view as the rover looked out of the bowl of Endeavour Crater. The robot field geologist captured the raw pictures that went into this image with her panoramic camera (Pancam). For more of Atkinson's work, visit his On the Road to Endeavour blog.Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth