Emily Lakdawalla • May 23, 2007

Windows Onto the Abyss: Cave Skylights on Mars

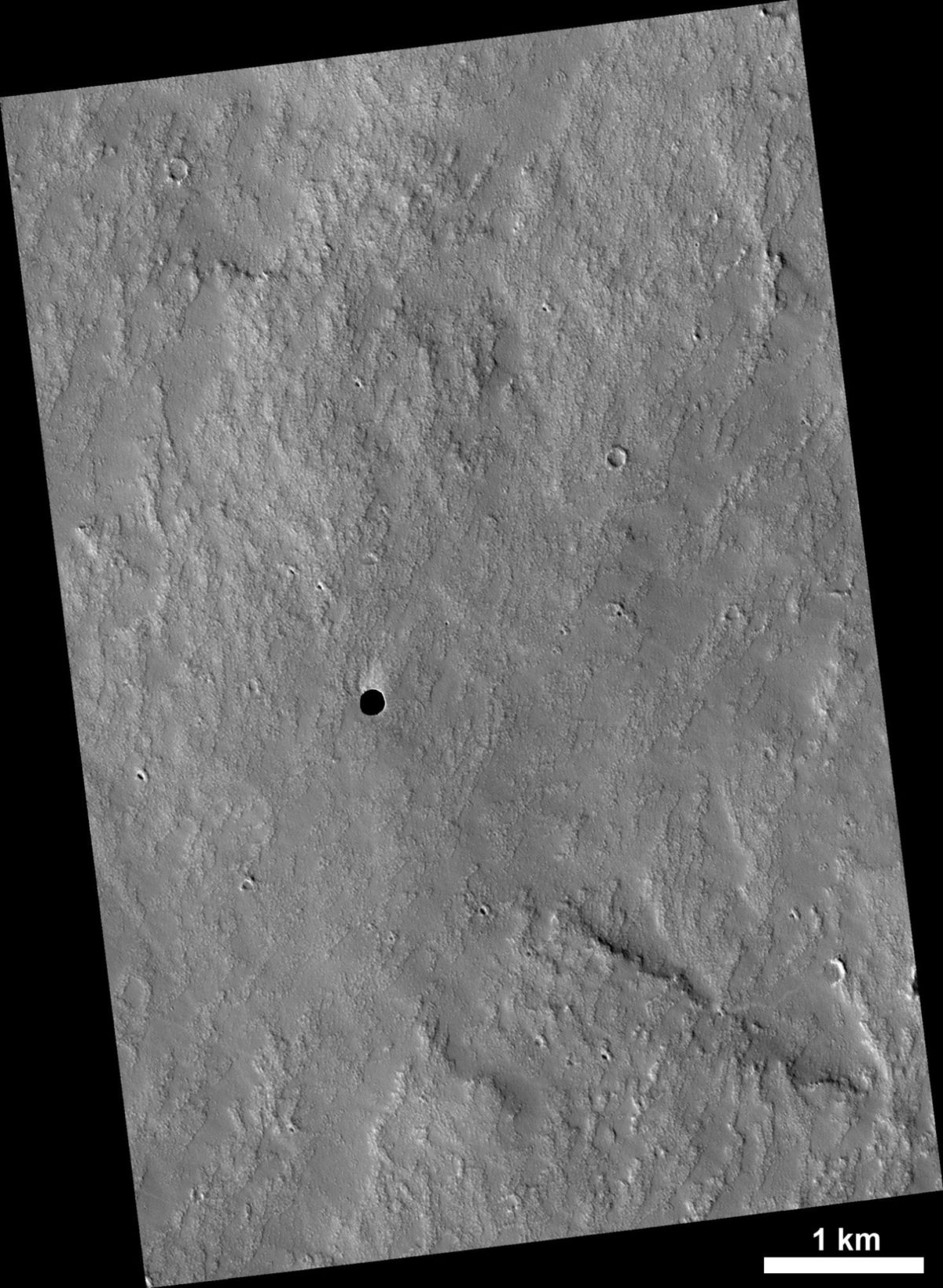

Today's set of image releases from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter HiRISE team included this one, of a fairly bland-looking lava plain to the northeast of Arsia Mons. Bland, that is, except for a black spot in the center. What's that black spot? It's a window onto an underground world.

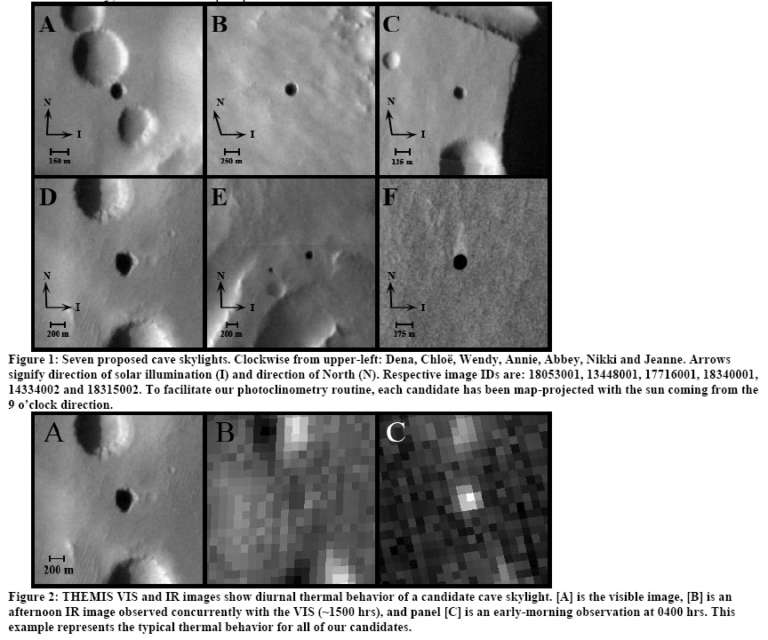

This black spot is one of seven possible entrances to subterranean caves identified on Mars by Glen Cushing, Tim Titus, J. Judson Wynne and Phil Christensen in a paper they presented at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in March (PDF format, 322k). Here's the figure from their paper that shows the seven caves, which they refer to by the names Dena, Chloe, Wendy, Annie, Abbey, Nikki, and Jeanne:

Dena (-6.084 N, 239.061 E)

Chloe (-4.926 N, 239.193 E)

Wendy (-8.099 N, 240.242 E)

Annie (-6.267 N, 240.005 E)

Abbey & Nikki (-8.498 N, 240.349 E)

Jeanne (-5.636 N, 241.259 E)Image: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / Cushing et al. (2007)

Their identifications were based upon Mars Odyssey THEMIS images, which achieve resolutions of a little better than 20 meters per pixel; having spotted the caves, they requested that the sharper-eyed HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter target the spots for more detailed imaging. The image above is the first one of these, and it shows the cave entrance called Jeanne. So what more can we learn from the HiRISE image? Let's check it out at full resolution (you'll have to click to enlarge for the full glory of 25 centimeters per pixel, a number I still goggle at every time I think about it).

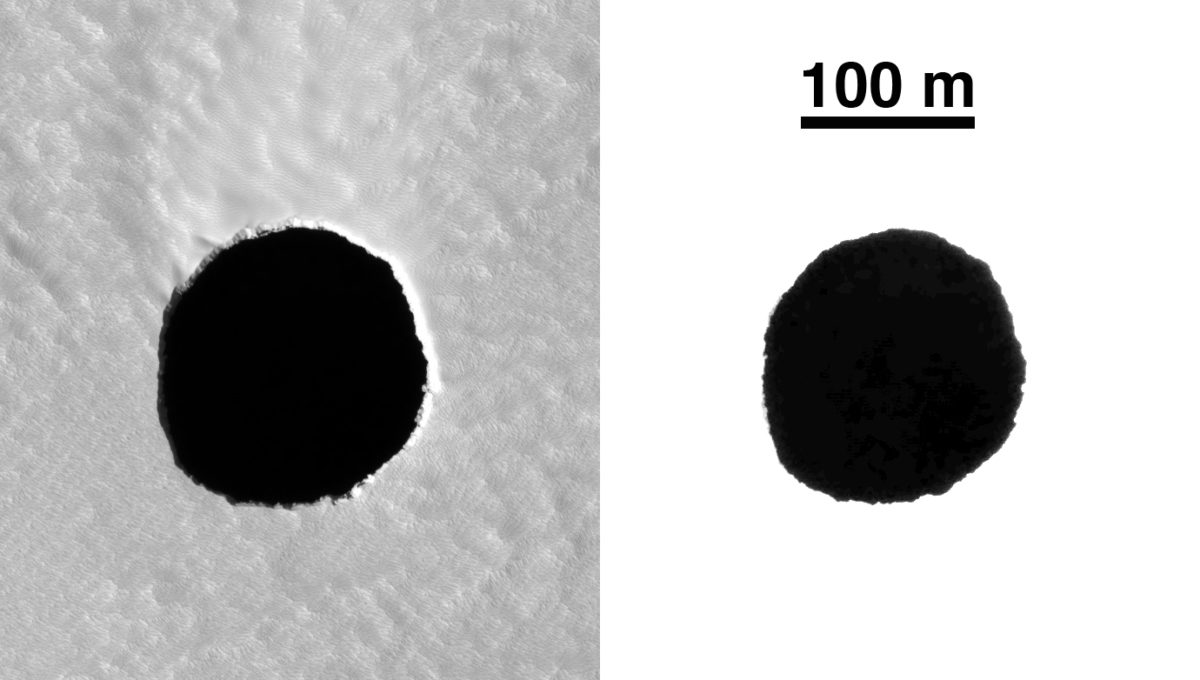

The hope for the HiRISE images was that we could see some details from inside the hole. But as you can see by the highly stretched version at right, there is absolutely nothing visible inside that hole. It's black black black black black. HiRISE is a very sensitive instrument, and Mars' dusty atmosphere scatters quite a bit of light around, so there is certainly light entering that cave hole and bouncing around the interior. But it seems that the cave is so big and so deep that almost none of the light that enters the cave comes out. It's deep, and it's big; the hole that we see really is just a skylight on a big subterranean room. How big? We'll never know for sure without visiting it, but I expect that Cushing and his coauthors and the HiRISE team will be crunching the numbers on the illumination conditions and the sensitivity of the camera to put a lower limit on how deep that cave must be for HiRISE to be able to see nothing at allinside it.

Think about that. All these orbiters at Mars, and most of them are just seeing the surface and atmosphere. To be sure, there are two instruments up there -- MARSIS on Mars Express and SHARAD on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter -- that are probing the shape of the subsurface with ground-penetrating radar. But neither of those instruments have the resolution necessary to tell us what the inside of this cave looks like. It might as well be in the greatest depths of space. Here there be dragons. What's down there? Are there stalactites and stalagmites and crystals, or is it just a vast open room or tunnel?

Maybe these spots will be explored by Martian speleologists someday. But that day is a distant one, I'm sure. Earth speleologists are only now exploring some of the biggest holes in our world.

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth