Jason Callahan • Sep 08, 2014

Growth. Peak. Collapse. Planetary exploration from 1959 - 1989

In prior posts, I have discussed NASA’s place within the federal budget, and the space science budget within NASA. In this post, I want to look at the role of planetary science at NASA, and what we get for varying levels of investment.

I focus here on flight projects only because I want to explain the effects of the budget on flight rates and mission sizes. Research and analysis, mission extensions, and technology development are all equally compelling as topics when discussing the effects of funding but are outside the scope of this post. I hope to address them soon.

Planetary Funding: The Grand Perspective

As we can clearly see, NASA has prioritized planetary exploration differently over time. When looking at the above plot, the line naturally divides into decades, with peaks in three of them and a plateau between. There are not in fact distinct breaks in the story of planetary exploration aligned with the change in decades, but dividing the story into five chapters can help clarify a very complex story.

In the plots below, I have listed all the solar system exploration launches through NASA’s history by launch date, mapped over the corresponding budget levels. Some of the missions may not appear to be planetary science in nature, but this list includes all missions NASA placed within their various lunar and planetary exploration budgets throughout the years. I have also color-coded the missions according to their cost profile:

Green = Small mission class (equivalent to Discovery), < $450M including launch vehicle

Blue = Medium mission class (equivalent to New Frontiers), < $1B not including launch vehicle

Red = Flagship mission class, > $1B

Examples of these types of missions are:

Small missions => GRAIL, Dawn, Pathfinder

Medium missions => New Horizons, Juno

Flagship missions => Curiosity, Cassini

1959 - 1969: The Space Race Era

In the 1960s, just about everything in space exploration was new. It was the time of the first robotic flybys of the Moon and other planets, the first time orbiting other planets, and the first time seeing the grainy images that they returned. Development was fast and furious during this period where rockets and spacecraft were unreliable and the USSR was a major competitor.

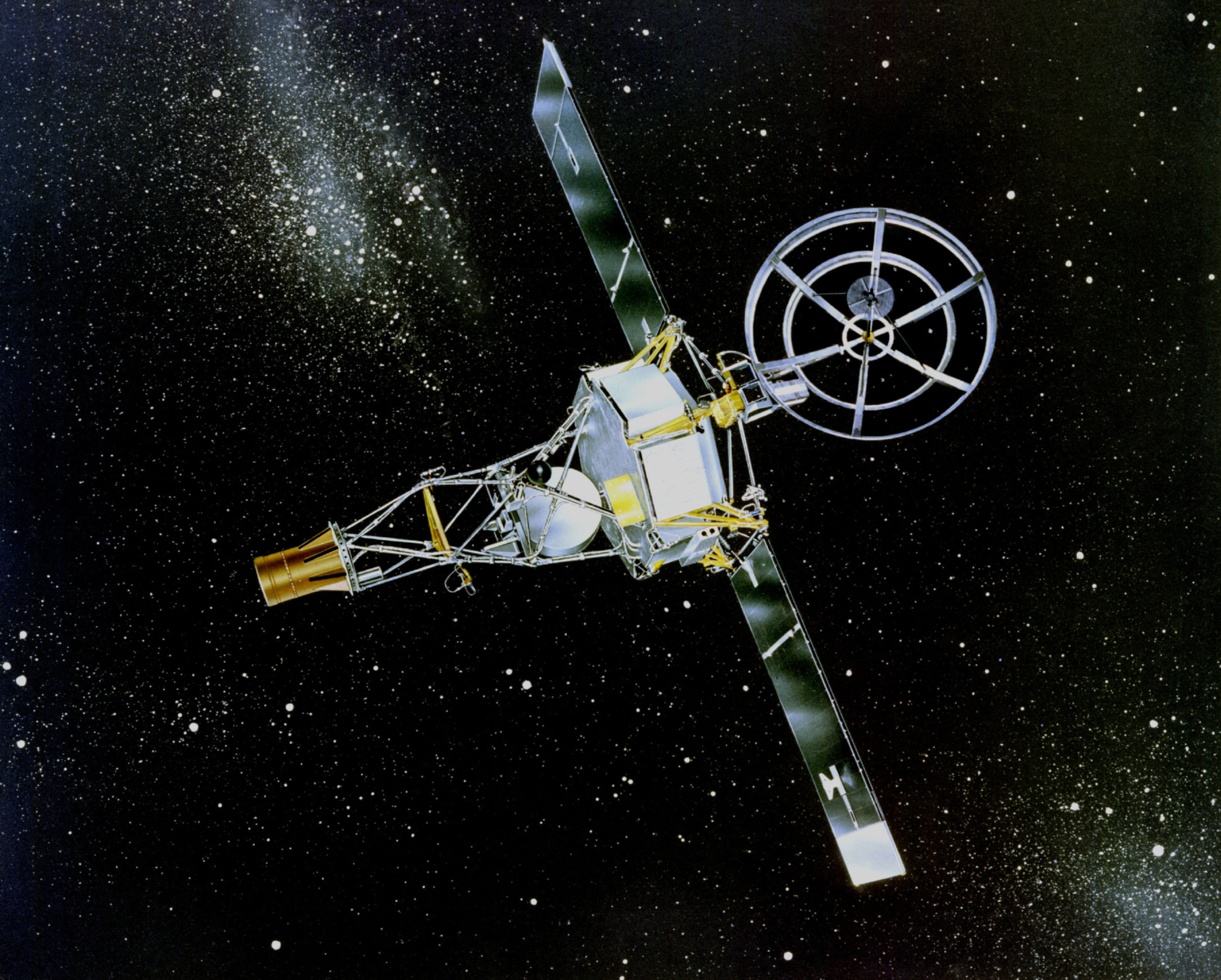

The U.S. Air Force and Army ran the early Pioneer program (including the Able launches shown in the above plot), while NASA launched them. Pioneer 6-9 were NASA missions orbiting the Sun and collecting space physics data, but NASA kept them within the lunar and planetary exploration budget line. NASA ran the Ranger program of lunar spacecraft, but the first successful mission in the program was Ranger 7. NASA’s first Mariner program, Mariner-Venus 1962 (Mariners 1 and 2), used spacecraft based on Ranger designs. In December of 1962 Mariner 2 successfully flew past Venus—NASA’s first robotic planetary exploration success. The second half of the decade brought a bevy of successful planetary flights, with varying levels of cost and complexity.

Looking at the plot above, you see that NASA’s planetary budget increased dramatically in the early 1960s and then decreased in the latter half of the decade. Also notice that the number of launches increased dramatically in mid- to late-1960s. The hump, or period of peak funding, was responsible for the increased number of launches towards the end of the decade, despite the fact that overall funding had fallen by that point.

The explanation for this phenomenon is critical in understanding NASA’s planetary program over time. The time it takes NASA and its partners to build a spacecraft varies greatly, but averages three to five years. NASA prioritizes projects in the process of being built – in development – over new project starts, so the effects of budget increases or reductions don’t affect launch rates for a few years. If the budget goes up, it will take a few years for new projects to be built before they launch. If the budget goes down, projects in development will continue but no new ones will start. The launch rate won’t decline for a few years.

As I mentioned in my last post, one of the dangers for the sustainability of NASA programs is the perception that, when the agency’s budget is reduced, things seem to still be going well for a few years, since projects in development continue. This means that we paid the development costs for the spacecraft being launched today in earlier years. Today’s budgets are paying for tomorrow’s missions.

The 1970s: The First Golden Age

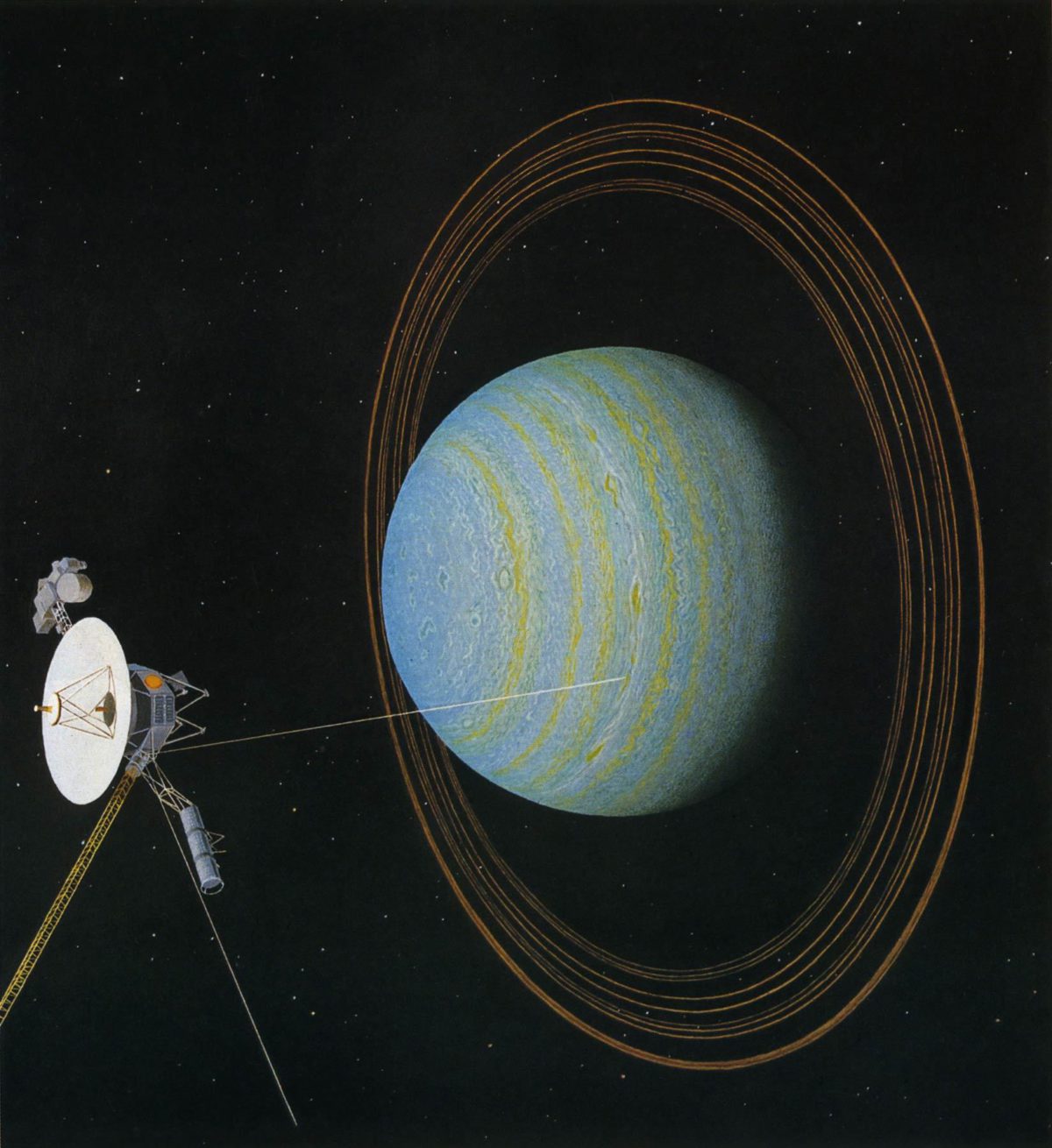

The 1970s represent a similar funding trend for planetary science as we saw in the 1960s, but with a new dynamic: an increase in the number of large missions and a decrease in the number of small- and medium-class missions. What is not reflected on the plot above is that, while the Mariner-Mars 1964, Viking, and Voyager missions were all flagship-class missions, Viking and Voyager cost two to three times what Mariner-Mars 1964 (Mariners 3 and 4) cost. The expense of the two flagship programs in the 1970s severely reduced the number of small and medium missions NASA could afford. We see this in the decreased number of missions listed in blue and green (Discovery- and New Frontiers-class, respectively).

The planetary science community came to recognize this trend as a serious problem. Large science missions are certainly able to return more (and more varied) data, since they carry more instruments and power, but the complexity almost invariably results in escalating costs and extended schedules. This in turn leads to fewer missions, meaning space scientists try to get their instruments aboard the large mission, for fear that it may be the last mission launched for years. This leads to greater complexity, and spiraling growth. A vicious cycle.

The long-term danger of this trend is that a program of more flagship-class missions—but fewer missions overall—takes a disproportionate toll on early career scientists, since they don’t have the credentials yet to compete with more established researchers. As we will see in the plot below, the flagship mission phenomena eventually led to waits of more than a decade between flight opportunities, which is more than a less-experienced researcher’s career can withstand. The planetary science community was sacrificing their next generation of scientists for a program of primarily flagship-class missions.

The 1980s: The Near-Death of Planetary Exploration

Within the planetary science community, the 1980s are often referred to as the “Lost Decade,” and the figure below shows us why. The budget cuts that began in the mid-1970s placed tremendous pressure on NASA’s planetary exploration ambitions, combined with NASA’s decision to launch all missions aboard the space shuttle and the shuttle program’s subsequent cost increases and schedule slips. For a period in the early 1980s, NASA seriously contemplated ending planetary exploration and divesting from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It was only through last-minute political machinations that the program survived, though at a greatly reduced capacity from the 1970s.

Just take a look at the moribund state of planetary science that decade:

When the space shuttle Challenger exploded on liftoff in 1986, one of the lesser—but not inconsequential—effects was a delay in NASA’s entire launch manifest for a period of years. NASA delayed the launch of Ulysses by four years, and Mars Observer by two years. Galileo, which began construction in 1977, was supposed to fly aboard a shuttle in 1984, and again in 1985, but the project schedule continued to slip. After Challenger, NASA delayed the Galileo launch to 1989. Between Pioneer Venus and Galileo, 11 years had passed without a new planetary exploration mission. The periodic planetary encounters of Voyagers 1 & 2 kept the field alive during this bleak period.

Growth. Peak. Collapse.

The first three decades of planetary exploration saw the evolution from a NASA that would miss the Moon to a NASA that could land on Mars on its first try. It also saw the near-death of this entire enterprise, where decades of hard-earned investments in technology and engineering skill were tossed away within larger political currents. If any of this sounds familiar, you will see a similar story over the next three decades, leading us into today. Stay tuned for that in my next post.

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth