A.J.S. Rayl • Aug 08, 2014

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Sets Historic Distance Record and Roves On

Sols 3710-3739

It's official: Opportunity has traveled farther and lived longer than any other vehicle on another planet, driving the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission to a place in history with an out-of-this-world distinction no one even imagined when the robot field geologist left Earth 11 years ago. As the MER team paused to celebrate the historic milestone at the end of July, the veteran rover was already roving on, making marathon tracks toward her next destination and kicking the bar higher for those rovers that have and will follow her to Mars' surface.

It happened quietly, over a period of sols or Martian days in July, and behind the scenes on Earth had involved previous months of calculations, recalculations, and verifications. But 10 years and six months after bouncing to a landing inside Eagle Crater, as Opportunity drove through ancient terrain along the western rim of Endeavour Crater heading for a new clayground to the south, the robot field geologist logged its 40th kilometer, and then its 25th mile to surpass the 39-kilometer (24.23-mile) record set by the Soviet Union's Lunokhod 2 rover on the Earth's Moon in 1973.

"There have been a lot of milestones during the course of this mission, but this to me feels like one of the more significant ones," reflected Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University. "The Soviet accomplishment with Lunokhod 2 on the Moon was obviously different in some pretty fundamental ways from what we've done with Opportunity, but what gives it significance for me is the history," he told the MER Update. "Lunokhod 2 was just an incredible technical achievement for its day. When you consider what they were able to do with 1973 technology, it was a truly magnificent accomplishment and they set a record that stood for a very, very long time. To be able to achieve something that's in that class feels pretty good. It has been an honor to follow in their historical wheel tracks."

On July 28th, NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the space agency center that is home to all the American Mars rovers, issued the press release announcing Opportunity's milestones and noting a joint effort between American and Russian teams with regard to the new distance record.

Opportunity sets record

Opportunity roved into a new place in history in July 2014, becoming the longest-lived most-traveled vehicle on another planet. This chart provides a comparison of the distances driven by various wheeled vehicles on the surface of Mars and Earth's Moon. Of the vehicles shown, Opportunity and Curiosity are still active and the totals listed are distances driven as of July 28, 2014.NASA / JPL-Caltech

It is, of course, kind of like comparing apples and oranges: Lunokhod 2, a successor to the first Lunokhod [which means Moon Walker], was delivered to the Moon on January 15, 1973 by the Luna 21 spacecraft, and then was driven remotely by a five-man team on Earth who basically joysticked the rover in real time for a period of less than five months. Opportunity has been roving for 10.5 years on Mars autonomously and by electronic command delayed by transmission time. But if one views the achievements from an evolutionary perspective, as Squyres does, it's easy to see that Lunokhod 2 and Opportunity are rovers of their times, each becoming a landmark mission in the history of planetary exploration that inspire the future.

"The Lunokhod missions still stand as two signature accomplishments of what I think of as the first golden age of planetary exploration, the 1960s and '70s," said Squyres. "We're in a second golden age now, and what we've tried to do on Mars with Spirit and Opportunity has been very much inspired by the accomplishments of the Lunokhod team on the Moon so many years ago."

The MER objective has always been about science, to explore Mars, so driving far enough to break the Lunokhod record was never a goal. At the same time, the way Opportunity has explored Mars and gone crater hopping all around Meridiani Planum—the way the engineers have delivered the scientists to the sites they want to see – is by driving far and wide. Out of the gate, Opportunity demonstrated that it really loved to rove, and year after year it has driven ever onward to defy all the odds.

So on May 15, 2013, when Opportunity roved past the NASA record of 35.74 kilometers (22.210 statute miles) driven by the Apollo 17 astronauts in their lunar rover, and moved into "second place," so to speak, the possibility of overtaking Lunokhod 2 was clearly in view. Silently, not surprisingly, it was on the rover bucket lists of just about everyone on the MER team. How could it not be?

To put it in perspective, back in the beginning, very few people outside the team dared to believe Spirit and Opportunity could land and complete their 90-day primary mission. Given that 2 in 3 missions to Mars failed, the odds were stacked against them. And despite the rovers' early successes, even MER engineers and scientists seriously wondered if Opportunity could actually make it to Victoria Crater. And Endeavour Crater – where the rover is currently uncovering some of the best science ever returned from the surface of Mars – well, it seemed like a distant pipe dream. The MERs were hardly designed to rove a marathon after all.

Opportunity, we know now, had her own plans – and those plans continue to astonish even her creators.

"It's a bit surreal to have been there at the very beginning, in 2000, when Mark Adler came into my office with his idea to shoehorn Steve Squyres' Athena Rover into our Mars Pathfinder lander design and submit a proposal for the 2003 launch window – and to now see Opportunity drive past 25-miles," said Rob Manning, the Mars Engineering Manager at JPL, who oversaw the rover’s system engineers and led the entry, descent, and landing (EDL) of Spirit and Opportunity.

"In our business, you have to think rather negatively in order for things to work at all," Manning explained. "Everything that could go wrong is factored into the design. We life-tested our wheels' motors for about three times the mission driving distance of 600 meters or about one mile. We then took the motors apart to see how much wear was on them (especially the notorious "brushes"). We found that some were worn and others were still pristine. We could not explain why. I would never have bet that Opportunity would see 25 miles under its treads," he said.

Although they designed the MERs without a built-in "ticking time bomb" that would kill the rover after so many sols – like, for example, Pathfinder's battery, which only allowed about 40 charge-discharge cycles – the chances either of the twins would survive a single winter on Mars was "unthinkable" then, said Manning. Plus, with the data they had from Pathfinder and Sojourner's solar panels, they estimated the longest they could hope to keep a rover running would be about 90 Sols or about three months. That was then.

Since then, Manning has bet friends at JPL that Opportunity would make it to another year. "But making it to and now past 25 miles – I am utterly amazed," he said.

Beyond besting the Lunokhod 2 record, the rover's new record, of course, is really testament to those who dreamed, designed, and built the rovers and to those who have kept the intrepid veteran operating day in and sol out for more than a decade. It is also testament to the MER team's "real time" example of what can be done when people work together as a team for a common goal. As much as anything, that's why this rover is still roving and why this record is such a crowning achievement.

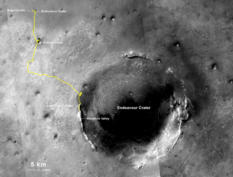

Opportunity's journey so far

Opportunity took our solar system's distance record for off-Earth driving in July, surpassing the Soviet Union's Lunokhod 2 rover that traveled 39 km (24.2 mi) in less than five months on Earth's Moon in 1973. Opportunity checked off her 40th km on July 20th, and then her 25th mile on the July 27, 2014, during a drive of 48 meters (157 feet) that brought total odometry to 25.01 miles (40.25 kilometers). The gold line on this image shows Opportunity's route from her landing site inside Eagle Crater, upper left, to the rover's location on the western rim of Endeavour Crater. The base image for the map is a mosaic of images taken by the Context Camera, onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

And, it's why within the extended MER team, the new record is an achievement that is deeply felt and humbly acknowledged. As John Callas, MER project manager of JPL, summed it up: "This is so remarkable considering Opportunity was intended to drive about one kilometer and was never designed for distance."

It was a long time coming.

Until last year, Lunokhod 2's record distance had been documented as 37 kilometers (about 23 miles). But in 2010 the Soviet Moon rover was located in images taken by the narrow angle cameras onboard LRO that had been imaging the Moon since 2009. As the images began to circulate the planetary science community, Irina Karachevtseva and her colleagues at the Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography (MIIGAiK), decided to take another look and re-calculate Lunokhod 2's total distance driven mileage using the LROC images.

Then a little more than one year ago, as Opportunity was closing in on its 37th kilometer, Squyres, who’d always wondered about the actual distance driven by Lunokhod 2 because 37 kilometers "seemed too round of a number," began a quiet investigation. "Before we made any claim about having exceeded the Lunokhod 2 record, we had to find out exactly what they really did," he said then. "I wanted to make absolutely certain that we really knew what the true Lunokhod accomplishment was."

Squyres reached out to the Russians through Phil Stooke, associate professor at University of Western Ontario, and author of The International Atlas of Lunar Exploration and The International Atlas of Mars Exploration. He then turned to MER science team member Brad Jolliff, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL), who is also a member of the LROC team and asked if he would measure the Lunokhod 2 traverse distance too.

Through Stooke and searches on the Internet, Squyres, Jolliff, and the MER team learned that Karachevtseva had determined the Soviet rover had driven 42.1 kilometers and presented this revised estimate at a scientific meeting.

Jolliff meanwhile was working with two graduate students, Ryan Clegg and Michael Zanetti, using different software and approaches. Initially, those tallies came out to around 39 and 40 kilometers respectively, as previously reported in the MER Update. But there was still work to be done and inconsistencies to sort out.

Although the Lunokhod tracks are remarkably well preserved on the Moon, "it's not easy to see everywhere it went," said Jolliff. "Even with the best LROC images where you can see the tracks really well, you still have to deal with the fact that you're projecting them onto a sphere and using mapping software. It was not an easy thing to do."

Jolliff and his grad students worked for several weeks, going back and forth between the two methods, working out internal inconsistencies until they were convinced the answer was "somewhere between 39 and 40 kilometers," said Jolliff. It was then he reached out to Karachevtseva, who agreed to work together and to compare estimates. "We then began what turned out to be about an eight-month project," said Jolliff.

By the end of January 2014, they had exchanged documentation, images, and written back and forth as to how each was measuring the tracks, defining the software and their differences, and comparing sets of LROC images. During that process, Jolliff realized the Russian team was using some of the first images from LROC. He gave her the image numbers his team was using to trace Lunokhod 2's tracks, images that "had the most favorable lighting geometry and best resolution, about ½ meter per pixel," as Jolliff described them. Karachevtseva's team then went to the public PDS site, got the images, and began the process of re-measuring Lunokhod 2's tracks.

Jolliff meanwhile wanted to double-check his team's estimate and turned to Mark Robinson, LROC principal investigator, and his team at Arizona State University (ASU). "Colleagues at ASU verified that we were projecting the data correctly, using the right geodesic parameters for mapping Lunokhod 2's path," he said.

At the same time, Jolliff wondered: "We're measuring the traverse distance of Lunokhod 2 by looking at orbital images and making measurements with those images map projected onto the planet. Has anybody done that for Opportunity?"

In fact, no one to that point had. For one good reason – the winds of Mars, which have already erased many of Opportunity's tracks. So, measuring Opportunity's traverse path on Mars with the imagery of the HiRISE camera (onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) alone – which wasn't even taking images until a year and a half or so after the Mars rover began her journey – simply couldn't be done the exact same way the scientists were measuring Lunokhod 2's tracks with LROC imagery of the Moon.

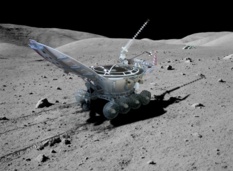

Lunokhod 2 on the Moon

This simulated image shows Lunokhod 2 as it might have roved on the Moon. The second of two unmanned Soviet rovers sent to the Moon in 1973, Lunokhod 2 held the international record for distance traveled on another planetary body until July 2014 when Opportunity claimed the title. For decades, it was stated that this "Moon Walker" traveled 37 km (23 mi) on the surface of Earth's Moon. But a revised estimate using images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) in 2014 bumped the Soviet's rover's total to 39 km (24.3 mi).Russian Academy of Sciences

Opportunity's distance has generally been tallied since she landed by totaling the meters the rover drivers record on the wheels at the end of each drive or, simply put, by wheel odometry. The Lunokhod teams did measure wheel odometry on their Moon rovers with the use of a cleverly designed 9th wheel, but the wheels weren't terribly accurate so Karachevtseva and her team had to rely to some extent on the historical record, especially in cases where Lunokhod 2 backtracked. Hence, a distance dilemma.

Still, the MER team wanted to verify that the map-based methods for computing distances are comparable for Lunokhod-2 and Opportunity, "to make sure it would be a fair comparison between the two measurements," said Callas, that it was "as close to an apples-to-apples comparison as possible."

For Opportunity's traverses, what they could do is look at each of the drive segments, because they knew point-to-point where Opportunity went in great detail. "We had a previous estimate done by MER science team member Ron Li and his group at Ohio State University that was actually a little less than what the rover planners (RPs) had from rover odometry, so we wanted to make darn sure," said Jolliff.

Li, however, recently went on to other things, so in January of this year, as Karachevtseva’s team and Jolliff’s team were nearing agreement, Jolliff asked Tim Parker, a member of the MER science team who serves as a Geology Theme Group Lead and who has been tracking and help charting Opportunity's path since the very beginning, to provide an independent tally for the total distance of Opportunity's entire traverse since landing in Eagle Crater.

Mark Maimone, a Navigation and Machine Vision researcher at JPL, who designed and developed the autonomous vision and navigation software that enables Opportunity and Curiosity to drive themselves safely, also joined the effort, basically to explain to the science team how the rover keeps track of its location, and what the mobility downlink tools that automatically process rover drive data here on Earth do to try and clean up that estimate.

"The rover's onboard software uses wheel odometry to 'predict' how far it travels along its path, while measuring its attitude using gyros in the IMU and sometimes measuring slip during the drive using Visual Odometry processing," Maimone told the MER Update. Maimone and his colleagues, actually, developed the software tools that automatically incorporate the small-scale slip corrections generated onboard by Visual Odometry into the overall detailed drive data.

"Whenever a Mars rover drives, the rover itself maintains an estimate of its position. This estimate is updated 8 times every second that the rover is moving, by combining its gyro-measured attitude with its distance driven, estimated by combining the wheel radius (12.5 cm) with the measured wheel rotation rate; our typical drive speed is 3.75cm/sec on the fastest-moving wheel," Maimone elaborated. "We normally collect up every 4th such update and transmit them to Earth, so on Earth we have a pretty complete log of rover positions sampled at 2 Hz throughout the entire mission."

Lunokhod 2 tracks on the Moon

On January 18, 1973, with a full battery charge, Soviet drivers in Simferopol, Crimea took Lunokhod 2 out for its first spin. The rover circumnavigated and imaged its faithful Soviet Luna 21 lander and then began its record-setting journey across the lunar landscape. Controllers operated the 8-wheeled rover mainly by using a mast-mounted TV camera and joystick controls. It survived four bitterly cold lunar nights as low as -240 °F, and racked up a newly revised estimated 39 km (24.23 mi). This image, which the LROC team posted on its site, shows a cross-like pattern of Lunokhod 2's tracks as it explored a small crater. For more LROC images: http://lroc.sese.asu.edu/posts/774NASA / GSFC / ASU

Sometimes, human rover drivers will ask the rover to "self-correct" its position many times during a drive, by comparing pictures taken before and after a ~1 meter step using Visual Odometry software. Those "self-corrects" are "pretty accurate," said Maimone. "But they require around 90 seconds of processing time, so to save time on Mars they aren't requested to be performed every step, except when human rover drivers think the rover might slip by a nontrivial amount." Those "self-corrects "result in "jumps" in the rover position. [For more, see: Mark Maimone, Yang Cheng, Larry Matthies, "Two Years of Visual Odometry on the Mars Exploration Rovers," Journal of Field Robotics

Understanding how the rover positioning and wheel odometer data are generated enabled the MER science team to better compare the rover-generated drive path against the orbital results.

Thousands of the Navigation Camera (Navcam) location images that Opportunity takes everywhere she drives, which are processed into large mosaics the ops team uses for planning, were also used to help verify the distances. "The Navcam images were put into overhead (orthorectified) projections and scaled to the base map that I compiled of the landing site from CTX and HiRISE images from MRO," said Parker.

Secifically, "JPL's Multimission Image Processing Lab (MIPL) team processes the Navcam stereo mosaics into 'point clouds' of x (east), y (north), z (elevation), and i (intensity of pixel) data that is used to generate a terrain mesh that is combined with my location maps (basemap with traverse path and current location) for the rover planners to use in planning the next traverse," Parker explained. "The Maestro software – which is the science-operations software used at JPL to support MER – makes a preliminary ortho-image (vertical projection) from the point cloud that extends 15 meters from the rover and I use that to derive the location to a precision of about 2 pixels (about a half meter) with respect to the HiRISE basemap."

So, to determine Opportunity's total distance, Parker projected Opportunity's entire traverse path on a base map of HiRISE imagery covering the entire route from Eagle Crater to Endeavour, 'editing' the placement of the Navcam overheads to match features in the base map, reporting the coordinates of the rover when it took those images, and measuring the length of the traverse path to that point. For initial placement, he used Maestro, and for coordinate determination and distance measurements, he used ArcGIS (ESRI), Global Mapper (Blue Marble Geographics), and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software.

"The final thing we had to do to make sure everything was comparable was to make sure the software we were using was using the same map projection,” said Parker, "and that the planetary radii for the Moon and Mars were correct in the tools that were being used."

"When Tim tallied it all up, we had a pretty good apples-to-apples comparison with the Lunokhod traverse on the Moon," said Jolliff.

Lunokhod 2 model

A rover joysticked by a team of Soviet controllers on Earth, Lunokhod 2 was about 170 cm (5’7”) long x 160 cm (5’3”) wide x 135 cm (4’5”) tall, and appears almost circular when viewed from above, according to a post at the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) website, by LROC Principal Investigator Mark Robinson, of Arizona State University (ASU). The vehicle featured 8 wheels and could travel at either 1 km per mile or 2 km per mile (0.6 and 1.2 mph). For more, visit the LROC website.ASU

But the MER team didn't leave it there. "Through the same kind of rigorous verification, we had Fred Calef, a geospatial scientist at Caltech who is also on the MER team, look at what Tim was doing, help work out any inconsistencies between our estimates, and verify the distance," said Jolliff. "That took a while to do."

During that time, Jolliff, Parker, Maimone, and Calef offered team presentations in the regular MER End-Of-Sol (EOS) meetings, explaining how they were measuring both Lunokhod 2's traverse and Opportunity's traverse. "In the end, we concluded that 39 kilometers was an accurate total distance for Lunokhod 2," said Jolliff.

Then, in late February, Karachevtseva contacted Jolliff and informed him that they agreed, 39 kilometers "looks right,'" said Jolliff. "So we had our estimate independent of hers, she had her estimates, and we came to an agreement that 39 kilometers (~24.2 miles) was Lunokhod 2's total distance," he said.

They knew there was some lingering uncertainty, but ultimately determined it was really quite small, all things considered, about 200 meters (0.2 kilometer or 0.124 mile).

Just to be positively, absolutely, unequivocally sure about Opportunity's newfound place in history, MER officials decided to hold off just a bit before making any announcements. “We wanted enough confidence that we were far enough beyond the uncertainty surrounding the Lunokhod 2 number, so we decided – because we were almost there – to wait until we hit 40 kilometers and 25 miles and make the announcements all in one swoop,” explained Callas.

As it turned out, Opportunity completed her 39th kilometer on April 19 (Sol 3639) while exploring the clayground along Murray Ridge, the area where data from the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard MRO show the presence of montmorillonites or aluminum-hydroxyl clay minerals that form, at least on Earth, in non-acidic water.

When the rover crossed that milestone, the MER team named a small 6-meter (about 20-foot) diameter crater on the outer slope of Endeavour's rim in honor of Lunokhod 2. Just five sols later, when Opportunity's odometer hit 39.22 kilometers, the sol MER actually surpassed Lunokhod 2's long-held record uncertainty included, the mission marked the occasion on Mars by having the rover that loves to rove pause near the crater and take some beautiful color pictures with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) to send home.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Lunokhod 2 Crater

When Opportunity logged her 39th kilometer in April, the MER team named a nearby crater in honor of her predecessor, Lunokhod 2, which held the off-Earth distance driving record for 40 years, and then had the rover take a bunch of pictures. "It was the Moon and not Mars, and it's different. Still, when you consider what they were able to do with 1973 technology, it was a truly magnificent accomplishment," said Steve Squyres, MER's PI. The Cold War was in full force in those days however, and most Americans knew nothing about this Soviet Moon mission. "If one of the things that we can do with this is to shine a spotlight on what the Russians did accomplish in those days, that's a good thing," said Squyres. Author, blogger, and MER poet Stuart Atkinson processed the raw Pancam images in this rich, Martian-technicolor for this view of the crater. It is a color close to, but not exactly, what it might look like if you were standing there. For more of Atkinson's images and musings, visit: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/Opportunity roved on in May and June characterizing the montmorillonite site along Murray Ridge, before getting back to making some serious tracks in July. "The montmorillonites seem to be everywhere in a low concentration and probably mostly a surface phenomenon," said Squyres. "We didn't do any RAT-ing so I can't tell you how deep it goes, but it seems to be kind of light alternation more or less everywhere. And I think the reason this area stood out in particular was largely because it was just at the time the CRISM data were acquired it was brightly light, facing toward the Sun so it had a higher signal than anything else around it," he added affirming Arvidson's assessment reported in last month's MER Update.

"We're beginning to get the sense that the Shoemaker Formation breccias in many parts of the rim of Endeavour are lightly altered to produce detectable quantities of clays and then the really interesting sites are the Noachian ones, like Matijevic Hill, like Esperance, where there has been very heavy alteration," Squyres continued. "That's what we're hoping to find when we get down to Marathon Valley."

Opportunity's claygrounds

This map shows part of the eroded western rim of Endeavour Crater and Opportunity's most recent and future clay mineral hunting grounds. MER Deputy PI Ray Arvidson, of WUSTL, and his graduate student, Valerie Fox, a MER science team member, mapped and color-coded the area where the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) detected clay mineral signatures over a base image taken by the HiRISE camera, also on MRO. Montmorillonite), signatures (Al-smectite) are highlighted in green at Moreton Island, which the rover investigated in Nov. 2013 and in blue along Murray Ridge, where it was working in May and June 2014. CRISM also detected nontronite (Fe-smectite) and saponite (Mg-smectite) clay signatures further south, in an area dubbed Marathon Valley, shown in red, where Opportunity is headed now. "The valley is likely to be a very rich hunting ground for us," said Arvidson, also a CRISM co-investigator.NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASU / R. Arvidson, V. Fox, WUSTL

As July dawned at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity had essentially wrapped up her survey of the montmorillonite area on Murray Ridge and was ready to begin the 2-kilometer (1.24-mile) journey south to Marathon Valley. She hit the road on Sol 3710 (July 1, 2014) and drove 26 meters (85 feet) that sol, stopping briefly mid-drive to take some color images with her Pancam. At the end of the drive, the rover took a full 360-degree Navcam panorama to document the new location and to help the MER ops team determine potential drive directions, a routine she would follow after every drive in July.

Marathon Valley – formerly referred to as the 'smectite valley' among team members because of the CRISM data indicating that the valley is rich with various kinds of smectite clay minerals – was at long last officially unofficially named to mark Opportunity's next historic achievement, completing that marathon – 26.2 miles or 42.2 kilometers – for which she was never designed. And by the time the veteran rover reaches the valley, that marathon should be run.

With 24.62 miles (39.62 kilometers) on her odometer, Opportunity began July "in good health," reported Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering at JPL, and ready to rove. Although the sky overhead was getting a bit dustier with the onset of the Martian spring – the rover was reporting an atmospheric opacity or Tau of 0.762 – Opportunity was still sparkling clean as a result of the winter blow-off, and able to utilize 87% of the sunlight hitting her solar arrays and was producing a robust 745 watt-hours of power, more than three-quarters her full power capability.

On Sol 3711 (July 2, 2014) Opportunity woke up, took some documentary Pancam images, then drove 24 meters (a little over 79 feet). While Americans celebrated a long Independence Day weekend on Earth, the robot field geologist continued her trek south with a 13-meter (43-foot) drive on Sol 3713 (July 4, 2014), heading toward an outcrop feature dubbed Broken Hills.

Every sol, Opportunity also took care of all the routine engineering and science chores. That included the clock correction task that the robot began in May, and on July 6th, the engineers had her increase the clock correction adjustment from 3 to 4 seconds to help speed the year-long process.

The robot field geologist wrapped up the first week of July by driving 19-meters (62-feet) closer to Broken Hills, taking more documentary imagery along the way, and then working in an overnight atmospheric argon measurement with her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) for an ongoing, mission long study.

July was all about driving and during the second and third weeks of the month, that's what Opportunity did. On Sol 3717 (July 8, 2014), the rover performed a drive-by shooting, taking pictures of a large fin that is part of Broken Hills as she passed by the feature on a 12-meter on the (39-foot) drive.

Between July 9th and July 17th, Opportunity drove six sols, putting another 243 meters (797 feet) on her rocker bogie over the 8-sol period. The rover paused to conduct some close-up work on a chosen target on Sol 3720 (July 11, 2014), the first sol of a two-sol, autonomous 'touch 'n go' where the rover used her arm to 'touch' a surface target called Trebia with her Microscopic Imager (MI) to take pictures for a mosaic, then placed her APXS on the target for an overnight analysis of the rock's chemical composition. On the next sol (Sol 2721; July 12, 2014), she drove on, completing the 'go,' logging 65 meters (about 213 feet) to a spot dubbed Minnesota River, with a mid-way stop, as has become the routine, to take pictures.

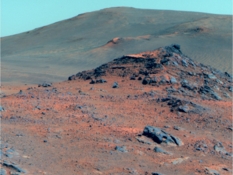

Happy 4th from Mars

Opportunity completed her survey of the montmorillonite site along Murray Ridge in July and began a 2 km (1.24 mi) journey to Marathon Valley, an area where CRISM shows a number of different clay minerals waiting to be characterized by the rover. As the robot field geologist headed out – and Americans were celebrating their Independence Day on Earth – she paused on July 4th and took this color picture postcard of this rocky ridge with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam). It was processed into this false color view shown here by the Pancam team. Who needs fireworks?NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Opportunity left Minnesota River on Sol 3724 (July 15, 2014) but during the drive experienced another Flash-induced reset event. Although these resets have occurred before, this was the first time that it happened during a drive. “We're not sure what this is telling us," said Nelson. "Normally we see these on a wake-up and the CPU is pretty busy during a wake-up – and we think it may have to do with the CPU being busy here too, and perhaps having some interaction with the Flash memory. The one good thing about this is it's a new symptom that may illuminate what's going on.”

The flight team was able to restore normal operations the very next sol and, from her stop point, Opportunity took Pancam and Navcam images, and on the evening of Sol 3725 (July 17, 2014) took another an atmospheric argon measurement with her APXS.

The robot field geologist began the first sol of another two-sol 'touch 'n go' on Sol 3727 (July 19, 2014), taking MI pictures of the target nicknamed Barstow, then placed her APXS on the same target for a multi-hour integration. Opportunity then suffered another one of those annoying Flash memory amnesia events believed to be caused by a corrupted sector. “It was similar to the other amnesia events we've had – it happened during the late evening after APXS work and during the wake-up to start a mini-DeepSleep," said Nelson. As with other amnesia bouts, the science data were lost in the Flash memory, but recovered with a subsequent second readout of the APXS, which also records the analysis.

Opportunity kept on truckin' and on July 20th – 45 years after Apollo 11 arrived at the Moon and 38 years after Viking 1 lander touched down on the plains of Mars – Opportunity logged her 40th kilometer while on a 100-meter (328-foot) drive, en route to a new target.

“We did make substantial drives and made progress pretty quickly during July," said Stroupe. "I won't kid about it. We did have our eyes on the prize a little and we all wanted to cross that 25th mile."

During the last week of July, Opportunity continued pushing south toward Marathon Valley, driving 99 meters (about 324 feet) on Sol 3730 (July 22, 2014), following what the scientists described as a "sinuous ridge" that may be a geologic "contact" between the Burns Formation over which the rover traveled during the first seven years of its mission and more ancient Grasberg Formation that the rover first found around the rim of Endeavour.

Heading for the Broken Hills

In July 2014, just a few sols after Opportunity began her 2-km journey south to Marathon Valley, the robot field geologist and her team saw this unusual ridge of rocks, with a distinctive fin-like rock, far upper right. The MER team dubbed the area Broken Hills, and had the rover do a "drive-by" to check it out. Stuart Atkinson processed this image into this 'suitable-for-framing' view.NASA / JPL –Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

On Sol 3732 (July 24, 2014) the rover continued south with a 72-meter (236-foot) drive, taking Pancam images before, during, and after the drive, along with a post-drive Navcam panorama as she had been doing throughout the month.

On the following sol, Opportunity collected an atmospheric opacity or Tau measurement to aid the forthcoming InSIGHT mission, and then on Sol 3734 (July 26, 2014), began another two-sol, 'touch'n'go'. The robot first took MI pictures for a mosaic of a surface target called Rosebud Canyon, then placed her APXS on the same target for a multi-hour integration for the 'touch.' Then, on Sol 3735 (July 27, 2014), Opportunity left Rosebud Canyon, driving 48 meters (157 feet) for the 'go.'

When she came to a stop, her odometer was at 25.01 miles (40.25 kilometers). Opportunity had crossed the 25-mile mark during that drive and at long last she had become the longest-lived most traveled rover on another planet. And on the next day, Opportunity rested.

Back on Earth, the Mars Exploration Rover's new record made the headlines and brought a lot of smiles and cheers around NASA, especially in the rover's mission control at JPL and in the offices of ops team members around the U.S. In many ways it showed, once again, that it's not what happens in life or on a mission so much as how it happens. "I feel very good about our collaboration with the Russians," said Jolliff, "and I think it's a good example of how the relationship among scientists from different countries in an international setting transcends the politics of the time."

Although the uncertainty surrounding the exact traverse distance of Lunokhod 2’s exact distance could have led to Opportunity’s latest achievement being something of an anticlimactic event when NASA issued the press release on July 28th, it was anything but. Rather, it was moment the MER ops team will remember forever.

“It is a bit surreal to think we've been going this long and for this far and we're finally there," said Ashley Stroupe, one of the rover planners (RPs) at JPL, who's been smiling a lot lately. "It's a really good feeling. Waiting for it to be acknowledged for so long and to finally have it official, the team is excited and really happy. We have definitely been celebrating.”

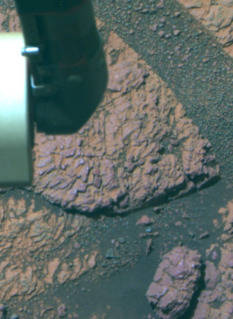

Where Oppy met Rosebud

On July 26, 2014, Opportunity's Sol 3734, the robot field geologist conducted another two-sol touch'n'go, a way of checking things out when the rover is basically in drive mode. First, the rover 'touched' a surface target nicknamed Rosebud Canyon, and then placed her APXS on the target to analyze its chemical composition. On the next sol, the rover drove off – and during that drive passed her 25th mile to take the off-Earth roving distance record. This image was processed by the Pancam team in false color, which enables scientists to better distinguish different parts of the geology.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

"It's a great accomplishment," marveled Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator of WUSTL. “Opportunity is so far beyond its warranty – and it's still roving.”

"I am very thankful that Mark came into my office and talked me into taking the plunge," said Manning. "It was the right thing to do at the right time. I am very proud to have been part of Opportunity's inception and creation, and I am especially proud to have been part of a great team of people from all over the U.S. and beyond to make them happen and succeed beyond our wildest dreams."

"It's pretty darn wonderful," summed up Parker.

"This has kind of re-charged the team,” said Nelson. "We are proud of our rover and the fact that the mission has returned so much science – and now that we have broken yet another record, we are extremely proud of that. We're ready to put another 2 kilometers on the odometer."

Never one to rest on her laurels, Opportunity took her new record and all the accolades – even the Tip of the Hat from Stephen Colbert – in stride and is focused now on getting to Marathon Valley. But first, the MER team decided to have the rover return on Sol 3737 (July 29, 2014) to an interesting target about 30 meters back to the north for further investigation and documentation, so Oppy retraced her tracks to the target now known as Cape Fairweather, and on Sol 3739 (July 31, 2014) she approached the rock.

As August dawned, the plan was for Opportunity to remain at Cape Fairweather for the first weekend of the month to do an up-close investigation, and then continue on her journey south. If all goes as it has been for the last 10-and-a-half years, the rover that loves to rove will easily put that next 2 kilometers behind her and bring her mileage to 42.2 kilometers or 26.2 miles and become the first rover marathoner on another planet.

In fact, the veteran rover is already well on her way. Having put 698.71 meters (0.434 mile) in the rear view mirror in July, she is, at month's end, only about 1.2 kilometers (about 0.81 mile) away from completing that marathon. “But what is really important,” said Callas, as he has said many times before, “is not how many miles the rover has racked up, but how much exploration and discovery we have accomplished over that distance."

Investigating Cape Fairweather

As July came to an end and August took over, Opportunity spent the weekend checking out an outcrop area dubbed Cape Fairweather and took this image with her Pancam, which was processed in false color by the Pancam team. Once the rover is done there, the plan is for her to continue her trek to Marathon Valley.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

So far the science returned by both MERs – Spirit and Opportunity – has, in the big picture, altered our perceptions of Mars and bolstered the long-held, popular theory that Mars was once warmer and wetter and more like Earth, with watery environments where life could have emerged and perhaps even taken hold. “We went to the surface with Spirit and Opportunity to back-out paleo environments and to understand whether or not Mars had water sustained on the surface or in the shallow sub-surface for a long period of time, a pre-cursor to whether or not the planet could have been habitable – and we hit home runs with both Spirit and Opportunity," said Arvidson.

“With Spirit, it was volcanic magmatic water interacting with sub-surface groundwater to produce fumaroles, steam vents, and hydrothermal stuff and with Opportunity we have seen lots of evidence from the Noachian Period with alteration of rocks in the presence of probably shallow groundwater," he said. "And for the Burns Formation, the bulk of what we've been exploring with Opportunity [and the terrain that is the floor of Meridiani Planum], we have evidence for a hugely areally extensive shallow set of lakes that would dry up and become wet again over a sustained period of time."

Opportunity has more to discover at Marathon Valley, where the various kinds of smectite clay minerals picked up by CRISM appear to be exposed close together and surrounded by steep slopes where relationships among different layers may unravel more of Mars' ancient history story. “We're in this drive mode now to get to Marathon Valley, but the scientists are finding interesting stuff so we are stopping along the way,” said Stroupe. “It's always a day-to-day thing. We never know what we'll see in the imagery that may cause us to go one direction or another. But we're pretty much heading due south, heading off course now and then to whatever catches our eye.”

MER has always been and will always be a science driven mission. Chances are though that Opportunity won't be stopping anywhere for long until it gets to the next clayground, The scientists wants to arrive at the valley well in advance of the next Martian winter, which should begin in February 2015, and the engineers, you can bet, have their eyes on that next prize. "The intention," said Squyres, "is to get to Marathon Valley in time to do significant science and exploration before winter sets in."

Opportunity certainly seems to be onboard with that. "The rover is healthy and doing extremely well," said Nelson. "We continue to enjoy the benefits of having clean solar arrays and the driving is good. In addition to that, the mood of the team is very upbeat right now. We're coming into spring on Mars and I think there's an awful lot of optimism about Opportunity’s future.”

In certain corners, it's a bold brand of optimism. “I’m looking forward to the next 10 years of this mission," said Parker, seriously.

Squyres, as readers of the MER Update know well, never makes predictions. But, asked to consider what it would take for Oppy to rove another 10 years, he said: "Everything's gotta keep working. It's real simple. There are a number of single end failures on the system, because our redundancy was to fly two rovers. But mechanically MER is a pretty robust design. We showed with Spirit that a wheel can fail and you can still have a mobile platform that can do fantastic science. A lot of Spirit's best science was done after we lost the use of the right front wheel."

Truth told, the MER team does have strategic plans for Opportunity that could make good use of the rover 10 years in the future. "You always have to plan for success," said Squyres. "But there's just no way of guessing. I'm looking forward to the next downlink, and I am serious about that."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

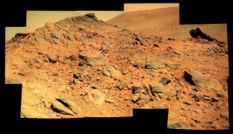

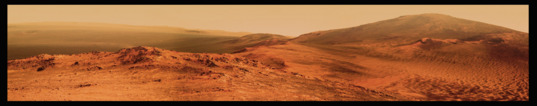

Oh, what another beautiful morning...Wish you were here

In July 2014, as Opportunity was driving south along the western rim of Endeavour Crater, headed for Marathon Valley, she paused as she always does, to take pictures. Stuart Atkinson took the raw Pancam images she took while driving during the middle of the month, stitched them together, and then processed them into the Martian-technicolor view presented here. It is a color close to, but not exactly, what it might look like if you were standing there. If all goes as it has been for the last 10-and-a-half years, the rover that loves to rove will easily put that next 2 kilometers behind her and bring her mileage to 42.2 kilometers or 26.2 miles and become the first rover marathoner on another planet. For more of Atkinson's images and musings on Oppy's truly excellent adventure at Endeavour Crater, visit: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/Still, bold optimism, along with Spirit's and Opportunity's MER mettle, is part of what made MER the mission it is. “It could happen,” mused Stroupe. “It really could. Yes, it is Mars. It's far away and anything could happen anytime. But there's certainly a big part of me that would not be surprised if we're still going five years or 10 years from now. You know," she added, pausing for a moment, "Opportunity will let us know when she's done.”

At this point however, "Little Miss Perfect," as rover pioneer Jake Matijevic affectionately called Opportunity, is roving on, leaving "done" for another distant sol down the road.

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth