Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 26, 2009

Updates from the Arctic Mars Analogue Svalbard Expedition (AMASE)

I've just uploaded about two weeks' worth of blog entries from Juan Diego Rodriguez-Blanco and Adrienne Kish on this year's Arctic Mars Analogue Svalbard Expedition; the latest entries are linked here. I enjoyed Juan's description of a simulated Mars mission so much that I thought I'd copy it below. Enjoy!

August 13: AMASE reunited (Kish)

ugust 14: Rock the Bock(fjord) (Kish)

ugust 15: The Goddess Departs (Kish)

ugust 16: From Muddy Depths to Whale Spouts (Kish)

ugust 17: Searching for Marvin the Martian in Murchison (Kish)

ugust 18: The View From Inside a Windowless Box: The SOWG (Kish)

ugust 19: A Final SLIce of Glacial Ice (Kish)

ugust 20: Dining with the Men in Black (Kish)

ugust 22: Science Operation Work Group: How to do science with a rover on Mars (Rodriguez)

ugust 23: Testing rovers for future Mars exploration: the goddess Athena drives in Svalbard (Rodriguez)

ugust 25: The End of the Road (Kish)

Science Operation Work Group: How to do science with a rover on Mars

Driving a rover on Mars and obtaining useful scientific information is something you don't learn from one day to another. You need a lot of training and you need to be able to work with people who have different scientific backgrounds. One way to learn it is by carrying out the Science Operation Work Group (SOWG) during the AMASE expedition. The 2009 AMASE SOWG was a combined NASA/ESA effort aimed at learning how to prepare for running future missions that will search for life on Mars.

Moreover, there are plenty of other possibilities: you can study the rocky material that is very close to the rover by using different analytical techniques, you can take high-resolution panoramic images with filters at different wavelengths, you can drive, select a rock, drill, or obtain microscopic images. But all these operations take time and cost energy. Your rover has limited mobility, navigational errors, limited bandwidth to connect with the Earth and not all the energy you would like it to. Moreover, you have quite limited time to choose what to do, because of the length of the Martian day and also the availability of the orbiters that are used to establish connection between the rover and the deep space tracking stations.

Exomars Pancam Group

The wide-angle view

Where would you drive? What are the interesting rocks to study? Is it better not to drive and use the energy instead to obtain high-resolution images? Should we drive only a little bit to get closer to the outcrop and use remote spectroscopic techniques to analyze specific rocks? What is the darker material near us? Are they outcrops, rocks with different composition or just shadows? This image is a composition of four pictures from the rover Navcams that were used for the SOWG mission scenario on AMASE 2009.This is exactly what we have been doing during the last two days on AMASE 2009. We are obviously not using information from the robotic explorers that are studying Mars at present. However, because Svalbard is the perfect terrestrial Martian analog on Earth, the Science Operation Work Group (SOWG) on AMASE can simulate a rover mission to Mars. So how do we do that? In a simpe way: one group of people is in the field obtaining the data (they are our rover) and another group is on the ship receiving it, discussing the possibilities and science questions/tasks we have set out to answer. All the people onboard ship are "blind" in the sense that they have not seen the actual site except via the "eyes" of the "rover". The SOWG group can not talk or connect with the people/rover in the field; they are only allowed to send them a file with the detailed instructions for the rover and that's it.

This year the task we were set as the AMASE 2009 SOWG was related to a Mars Sample Return mission and the mission scenario was the following: "a successful landing took place in a large impact crater considered to have sedimentary deposits. During the first 100 sols (Martian days) the rover travelled through a mixed sedimentary scree considered to be primarily impact ejecta. Using orbital images, the mission scientist identified probable bedrocks, so the rover took all that time to travel there. Today, at the end of sol 99, the rover position was at only 50 metres of the outcrops and commanded to move to a distance of 10 metres from them". Our mission: to decide what areas to study, where to go and what analyses to do in order to take one sample of astrobiological interest to return to the Earth.

ExoMars Pancam Group

Areas selected for further study

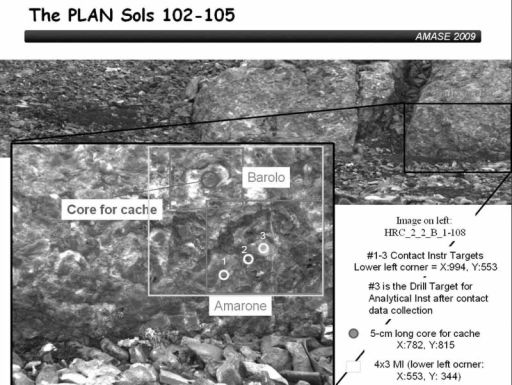

The outcrops have been studied in detail and the SOWG team has selected a list of activities for the rover, indicating which are the most important ones. For this area we planned high-resolution microscopic images, infrared and Raman measurements, drilling cores for elemental analyses, etc. and coring for cashing for sample return.Carrying out the task is not so simple and there has to be a structure in the group: there is a SOWG chair (Doug Ming) that leads the SOWG team and has the final say on the activities if consensus cannot be reached. There were people responsible for the rover scientific instruments (cameras, spectrometers, different analysis systems, drilling tool, microscopic imager...). Finally all of us were distributed into three science theme groups that analyzed the data and prepared the activities requests for the full SOWG meeting: geomorphology, mineralogy and geochemistry, and life sciences. Steve Squyres was the mission manager, the single point of contact between the SOWG and the rover and also he was the responsible person to provide answers to questions regarding rover capabilities, resource utilization, etc.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth