The full story of Earth-impacting asteroid 2008 TC3

Written by

Emily Lakdawalla

October 7, 2008

Over the last 24 hours it has been tiring but really fun to watch the drama of asteroid 2008 TC3. It has happened so quickly that it's necessary to convert all times to UTC in order to see how events have unfolded across the globe. Fortunately for my sanity, nearly all of the events are neatly collected on the Minor Planets Mailing List.

To briefly review: the night before last (my time), or at 06:38 UTC on October 6, astronomers at the University of Arizona discovered an object provisionally called 8TA9D69 that appeared to be on a collision course with Earth. Three other observatories reported sightings within the next few hours -- Sabino Canyon in Arizona and Siding Spring Observatory and a Royal Astronomical Society site, both in Australia. Together these four observers provided enough data on the object so that a Minor Planet Electronic Circular was issued at 14:59 UTC the same day, giving 8TA9D69 the more formal name 2008 TC3, and advising the astronomical community that "The nominal orbit given above has 2008 TC3 coming to within one earth radius around Oct. 7.1. The absolute magnitude indicates that the object will not survive passage through the atmosphere. Steve Chesley (JPL) reports that atmospheric entry will occur on 2008 Oct 07 0246 UTC over northern Sudan."

Eric Allen, Observatoire du Cegep de Trois-Rivieres, Champlain, Québec, Canada

Images of 2008 TC3

Eric Allen observed asteroid 2008 TC3 as it approached its impact on Earth on October 7, 2008 at 01:32 and 01:42 UTC. The fast motion of TC3 makes it stretch out as a dashed line in these two photos, which is made of several 10-second exposures, separated by 10 seconds each. The two images were taken only 10 minutes apart. In the intervening 10 minutes, under the influence of Earth's gravity, TC3 had noticeably sped up and shifted direction as it approached its impact at 02:46 UTC.With the object so close to Earth, the parallax of different observers on different parts of the globe allowed much greater precision than is usual, given the short observing arc. The initial impact prediction was confirmed by JPL scientist Paul Chodas at 01:45 UTC: "We estimate that this object will enter the Earth's atmosphere at around 2:45:28 UTC and reach maximum deceleration around 2:45:54 UTC at an altitude of about 14 km. These times are uncertain by +/- 15 seconds or so."

After positional information, the next challenge was to obtain spectral data -- information on the color of the object, which would help to classify it and determine its origin. The first I heard of such data being captured successfully was from this item on the MPML by Alan Fitzsimmons and coworkers at Armagh Observatory: "We obtained optical spectra of 2008 TC3 using the 4.2m William Herschel Telescope and ISIS spectrograph on Oct 6.93-6.94UT. The spectra cover the range 546-995nm at a resolution of 4nm. Initial analysis of the spectra via comparison with the solar analogue 16CygB reveals a featureless reflectance spectrum with no indication of the silicate absorption feature longward of 800nm." Presumably there were other observers who were able to obtain spectral data, though not as many as were gathering positional information.

Time quickly ran out to observe the asteroid, however. Astronomers in Spain recorded 2008 TC3's entry into Earth's shadow, hiding it from view for its final hour of descent. The image is below:

La Sagra Sky Survey, Spain

2008 TC3 disappears into Earth's shadow, on its way to impact

Traveling from right to left in this image, asteroid 2008 TC3 entered first the umbra (at 1:47:30 UTC) and then the penumbra (at 1:49:50) of Earth, disappearing into shadow for the final hour of its approach to burning up in the atmosphere over Sudan. The view is a six-minute exposure tracked at sidereal rate (so stars stay fixed). Exposure start time was October 7, 2008, at 01:45:23 UTC. The view is half a degree wide, comparable to the size of the full Moon. At the start of the exposure 2008 TC3 was at a distance of 29,600 kilometers, approaching at a speed of 7.61 kilometers per second. The periodic light variation along the early part of the trail indicates a fast rotation of the intruder around its spin axis.And there's more than one way to detect an asteroid impact. Even in relatively unpopulated areas, there are seismological stations scattered around the world, using infrasound to record seismic events. One such station seems to have detected a 1 to 2-kiloton blast associated with the impact. This is according to Peter Brown, of the University of Western Ontario [hey, that's the same university that's home to asteroid mapping genius Phil Stooke]. Brown said:

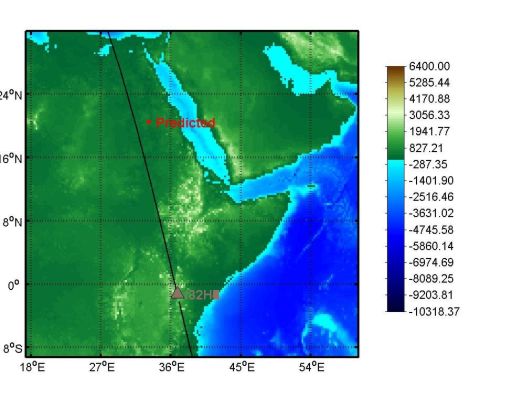

A very preliminary examination of several infrasound stations proximal to the predicted impact point for the NEO 2008 TC3 has yielded one definite airwave detection from the impact. The airwave was detected at the Kenyian Infrasonic Array, (IMS station IS32), beginning near 05:10 UT on Oct 7, 2008 and lasting for several minutes. The signal correlation was highest at very low frequencies -- the dominant period of the waveform was 5-6 seconds. The backazimuth of the signal over the entire 7 element array is shown in the attached map -- it clearly points to within a few degrees of the expected arrival direction. Moreover, assuming a stratospheric mean signal speed of 0 28 km/s, the arrival time corresponds to an origin time near 02:43 UT, which is consistent with the expected impact time near 02:45:40 UT given expected variations in stratospheric arrival speeds. The dominant period of 5-6 seconds corresponds to an estimated energy (using the AFTAC period at maximum amplitude relationship from ReVelle, 1997) of 1.1 -- 2.1 kilotons of TNT. The five other closest infrasound stations were briefly examined for obvious signals and showed none -- more detailed signal processing of these additional data are ongoing in the search for additional signals.

But of course we now have to ask ourselves: what would have happened if the object was much bigger than 2 meters in diameter? Reassuringly, the first thing that would have happened is that the detection most likely would have happened much earlier. The bigger and more hazardous an object is, the brighter it is, and the sooner we will detect it. We will likely have way more than 20 hours' warning of an incoming dangerous object. Still, though, the warning time for a tens-of-meter-diameter object could only be measured in days. If we'd had three days' warning of a dangerous impactor heading for Sudan, what could the world have done? The remote location of the impact would have been fortunate for humanity in general, but disastrous for the few people who lived out in that remoteness. Could the developed world have done anything to prevent yet another humanitarian disaster from befalling the Sudanese?The Planetary Society is seeking answers to these questions. We have joined the Association of Space Explorers and the B612 Foundation in their efforts to develop an international framework for planetary defense, and we plan to hold both an invited workshop and a public meeting on these issues in the summer of 2009, as a part of the International Year of Astronomy. When the time is right, we will push for action on this issue from the United Nations' Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. A final plea to wrap up this story: if you'd like to support these efforts to protect our planet from hazards from space, please vote with your wallet by sending a donation our way. Any amount is helpful!

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth