It's so crazy it just might work: Send Cassini between the rings and the planet

Written by

Emily Lakdawalla

April 10, 2008

Although the first mission extension for Cassini hasn't officially been approved yet by NASA Headquarters (which strikes me as being kind of silly, since the primary mission comes to a close in less than two months!!), the mission is already trying to figure out what to do beyond the two-year proposed Extended Mission. Last week there was a meeting of the Outer Planets Assessment Group, and Cassini's Deputy Project Scientist, Linda Spilker, gave a presentation on what to expect from the extended missions (here it is, in PDF format, well worth a look). There was a lot of stuff about the science to be expected from the extended mission, and a proposal for an extended-extended mission, but the real stunner was a scenario she presented for Cassini's end-of-life: to spend the very, very last phase of the mission in an orbit that threads Cassini between Saturn's cloud tops and the innermost D ring.

NASA / JPL / SSI

Saturn from above

his view of Saturn shows the night side of the rings, a geometry that lights up the faint C ring, the innermost ring that's visible here. In the apparently black space between the C ring and Saturn is another, far fainter ring called the D ring. Only a tiny open space, about 3,000 kilometers across (that's a distance only 2.5% of Saturn's diameter) exists between the D ring and Saturn, and Cassini may be flying through it repeatedly toward the end of its mission.

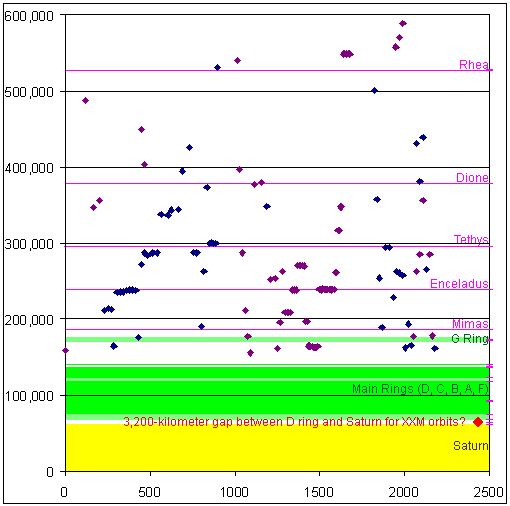

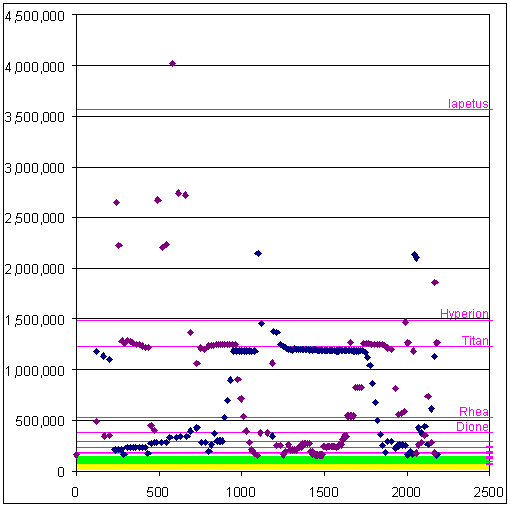

Just to give you some context, here's a plot of all of Cassini's ring plane crossings through the prime and extended missions. The X-axis is in days since orbit insertion, and the Y axis is distance from the center of the Saturn system in kilometers. You can see that most of the ring plane crossings have happened within the orbit of Hyperion, and that many of them occur at Titan's orbital distance from Saturn. This is no coincidence -- all the moons also orbit in the ring plane, and Cassini uses close encounters with Titan to adjust its orbit (and also study Titan). So many of the ring plane crossings happen at Titan's distance from Saturn.

Emily Lakdawalla

Cassini's ring plane crossings

The X-axis represents time (days from orbital insertion); the Y-axis is distance from the center of Saturn. Magenta horizontal lines denote the orbits of the large moons. Green denotes rings A-G. Yellow denotes Saturn. Blue and purple diamonds denote the distances at which Cassini's orbit takes it through Saturn's ring plane. Blue diamonds are ascending ring plane crossings (from south to north), and purple are descending ring plane crossings (from north to south).As usual when I have questions about Cassini's orbit I asked Dave Seal to explain things to me. First of all, how do you lower the orbit periapsis from outside the ring system to completely inside the ring system without somewhere crashing into the rings? Dave said simply that the tour designers figured out how to do it with just one Titan flyby; Titan flybys can change Cassini's speed by hundreds of meters per second, and "that's enough to go from just barely outside the F ring all the way to between the D ring and the planet" with just one gravity assist flyby of Titan.

NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

Changes in the D ring from Voyager to Cassini

A view of the D ring from Cassini is compared to a view from Voyager at comparable viewing geometry. The boundary between the C ring and D ring is marked on the Cassini image by a green line. The C ring is overexposed in the lower left corner of the Voyager image. The outer D ring feature called D73 lines up perfectly between the two images, separated by 25 years. So does an inner D ring feature called D68, near the right sides of the two images. But in the middle, the brightest feature in the Voyager image, called D72, does not line up with any feature in the Cassini image. The inset view shows the region outside D73 with its closely spaced wavelike features, so regular that they could be the grooves in a vinyl record.A big question is how the orbit can be stable. Saturn is very noticeably non-spherical because of its fast rotation rate coupled with its low density -- it bulges hugely at the equator, making it "oblate." This oblateness means that the gravity field is a bit complicated, and exerts weird torques on orbits of bodies that are not orbiting in the ring plane. If you want the nitty gritty details about what happens to an inclined orbit under the effect of Saturn's gravity, Dave said:

The oblateness precesses both the line of apsides (the periapsis-apoapsis line) and the line of nodes (the line connecting the ascending and descending nodes = ring plane crossings). Think of the former as rotating the orbit in its own orbit plane, and the latter as rotating the orbit about Saturn's axis. The former moves the radii of the nodal crossings; the latter does not, it just moves their longitudes (or local solar time). The apsidal rotation goes to zero at what we've been calling the "critical inclination" which is about 63.5 degrees. So if you use Titan to crank the orbit up to 63.5 degrees inclination, all Saturn's oblateness does is precess the orbit in local Solar time (again, about Saturn's pole axis). You can then jump over the whole ring system at that inclination and the nodal radii stay right where they are - you don't get precessed into Saturn's rings.

At this stage, this idea for the end of the mission is hypothetical (especially since, as I said, they haven't even formally approved the extended mission yet, much less a second extension). There are other end-of-mission scenario ideas being tossed around, but as you might imagine this one is really getting the Saturn atmospheric, magnetospheric, and rings scientists -- basically, everyone but people who like to study the moons -- incredibly excited. Cassini could last many months in this configuration, jumping over and through the rings, descending deep into the magnetic field and charged particle environment, photographing the tops of the clouds from only 3,000 kilometers away (although at a high relative speed of 34 kilometers per second), and still jumping back out for the occasional Titan flyby. And they might not need to implement this endgame scenario for 6 or 7 years after the end of the extended mission, long enough for Cassini not only to see Saturn's equinox (which will happen in the middle of the first mission extension) but to see Saturn almost all the way through to the next solstice.

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth