MSL landing site meeting: Getting beaten up is good for science

Written by

Emily Lakdawalla

September 16, 2008

These landing site selection meetings are fascinating because I don't know of any other venue in which so many scientists get together and participate in open discussion (and, yes, even pointed argument). Ordinarily, in planetary science, there are talks, followed by a brief question-and-response; even for the most controversial talks, there are usually only a few minutes for discussion, and no back-and-forth, only comment and response, and then it's on to the next talk.

This meeting (and the others like it in the past for MSL and the rovers) is structured differently. Small groups of researchers propose, and advocate for, one landing site. They perform all the studies they can do from orbit to identify a site's geomorphology (the shape of the landscape), its mineralogy (what mineral components can be spotted from space), the stratigraphy (order of events), and so on, and then bring together all of that to tell a story about the site's geologic history and why it is the best place to send the MSL rover. They present the results of those studies. And then the site is thrown open to discussion, forty minutes or an hour of discussion, in which the room argues back and forth about the interpretations, brings up possible alternative interpretations, questions the conclusions, attacks each other's assumptions, and generally beats the stuffing out of the hard work that each research group has done. It's mostly civil, but sometimes gets pretty testy; I think that the fact that the format works at all owes a lot of credit to the facilitating skill of the workshop leader, Mars scientist Matt Golombek.

This morning, for instance, I was watching presentations being given on the Nili Fossae region, an area I've talked about before because, from space, it is really beautiful. Looking at the presentation being given by Jack Mustard, I practically salivate over the possibility of exploring this landscape, and I know the mineralogists would love to examine the rocks, whose diverse compositions just yell themselves out into space with bright colors in CRISM and OMEGA spectrometric images.

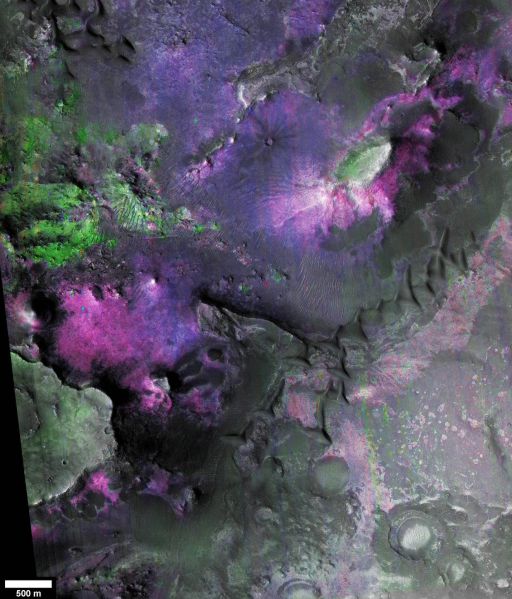

NASA / JPL / U. Arizona / JHUAPL

Nili Fossae Trough from CRISM and HiRISE

The blooming purples and greens in this image of the west wall of Nili Fossae, northwest of Mars' Isidis basin, map the signatures of minerals in the Martian bedrock that scientists hope to sample with a future rover. The floor of Nili Fossae (lower right) is paved with volcanic materials; "shark's-tooth" dunes of dark basaltic sand march parallel to the northwest wall of the trough. An ancient flooding event cut into that wall, carving a landscape of mesas and buttes and exposing ancient bedrock. In the bedrock, the CRISM imaging spectrometer reveals in blues and magentas locations where CRISM sees the spectral signature of phyllosilicates, minerals that form when igneous minerals such as pyroxene are altered in the presence of water. Greenish colors imply the presence of low-calcium pyroxene, a mineral that formed very early in Mars' history with the hottest volcanic activity.If the Nili Fossae site received a hammering today, it was not quite as bad as the beating delivered to the Miyamoto site yesterday, where there was the same criticism about no evidence for water sticking around for a long time, and even an assertion that the so-called river activity was actually volcanic, not water, channels. Ryan Anderson has a more detailed summary of the discussions of the merit of the Miyamoto landing site. I concur with his conclusion; it seems the research on Miyamoto is just not as mature as on the other sites, and there are too many doubts about it in the community, for it to survive past this meeting. (Ryan also summarizes the discussion on the 'safe' landing site, South Meridiani, which I missed yesterday.)

Today I am getting a negative feeling about Nili Fossae, but then I'll have to wait and see how hard the roomful of scientists (there are more than a hundred people here) pokes at some of the more lake-like sites, including the one that's being presented now, Holden crater.

It's really rare that scientific studies are exposed to such an open environment of skepticism and questioning. It must be tough on the presenters but in the end MSL is going to go to the landing site about which there are the fewest doubts, the lowest risk for science -- so, hopefully, present suffering will yield a better mission. And doubts raised about the selected landing site will lead to pointed investigation of the site in the months leading up to the landing. We have a wealth of orbiting assets with which to study these places before the rover lands -- the best-prepared teams here are even planning the eventual multi-kilometer driving path of the rover, using the incredible resolution of the HiRISE images for their base map. More than any previous mission, MSL is going to be able to hit the ground running. (Assuming, of course, it survives when it hits the ground!)

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth