Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 17, 2007

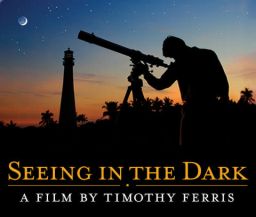

Seeing in the Dark

A former college classmate, Mark Andrews, emailed me a couple of weeks ago saying, he was working on a new PBS production on stargazing amateur astronomy, would I care to preview and review it? It is "Seeing in the Dark," based on Timothy Ferris' 2002 book of the same name. In brief, I definitely recommend it; check your local PBS' station's listings to find when and where it airs. (It'll be on Wednesday the 19th at 8:00 Eastern / Pacific for most PBS stations.)

Robert Gendler

Andromeda Galaxy

This stunningly detailed color mosaic of the Andromeda galaxy was captured by amateur astrophotographer Robert Gendler. It required almost 90 hours of exposure time, and the full-size original image is 21,904 x 14,454 pixels in size (one Gigabyte!). The version here has been downsized by a factor of approximately seven.Face-to-face interviews give you a view into their enthusiasm. The people featured in the show are transported across space and time as they play with their telescopic toys. Yet most of them really do observe from their backyards, some of them from fairly light-polluted backyards. One of my favorite scenes showed one of the amateurs going out at night and mounting a stepladder to throw a barbecue grill cover over a street lamp located annoyingly close to his backyard observing location. ("His neighbors must hate him," my husband remarked.)

The show makes the point that although astronomy is not a cheap hobby, it is certainly within the reach of many thousands of enthusiasts. For the kind of money that many people will spend on a motorcycle or boat for weekend fun, you can outfit yourself with a pretty fancy home observatory, or even one sited in a dome in a remote dark-sky location that you can control from the comfort of your own home. As a little stunt for the show the Bisque brothers (hardly amateurs) see how fast they can set up and install a working remotely operated system in one such dome in New Mexico. The answer: three hours. Once set up, you not only get to see beautiful objects in space -- planets, galaxies, open clusters, and nebulae were all featured in eye-catching images -- but you can actually get involved in science, participating in observing campaigns to catch the afterglow of gamma-ray bursts, search for extrasolar planets, and track potentially hazardous asteroids.

Refreshingly, the production relies almost entirely on real film footage and stills, going to special effects only when no actual images will do (for instance, to show an animation of a supernova producing a black hole). The production seems to employ some of the same stillness that sky watchers enjoy; there is none of the quick MTV-like cutting from image to image that has become so distressingly common on television.

There was only one sour note: I could have done without the obviously scripted scenes involving Timothy Ferris and his son. It made for a nice story arc, and Ferris' own lifelong interest in astronomy was clearly important to his ability to produce the book and film, but Ferris just wasn't able to pull off the acting performance. It was the only thing that rang false in a show that was otherwise about people's true love for the stars.

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth