Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Moves to New Targets, Opportunity "Sails On" Around Victoria's Rim

Written by

A.J.S. Rayl

Contributing Editor, The Planetary Society

November 30, 2006

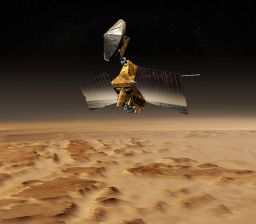

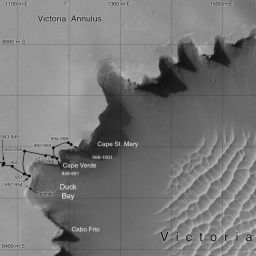

Two HiRISE views of Opportunity at Victoria

Two HiRISE views of Opportunity at VictoriaThis image shifts between two HiRISE views of Opportunity on the rim of Victoria crater taken on October 3 and November 14, 2006 (Sols 957 and 998). Between these two dates, Opportunity drove from Cape Verde to Cape St. Mary.

Credit: NASA / JPL / U. Arizona / Emily Lakdawalla

With both a superior conjunction and a long, Martian winter behind them, the Mars Exploration Rovers picked up the pace in November and drove on to new locations and research.

At long last, Spirit moved this month, after working from the same position for nearly 7 months at Low Ridge in the Columbia Hills region of Gusev crater, keeping its solar arrays tilted precisely to capture as much of the winter Sun as possible. The rover has since examined several chosen soil and outcrop samples and is preparing now to head out of Low Ridge. "The winter campaign is wrapping up and Spirit will really begin driving soon, as early as this weekend, " Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator for rover science and a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, said in an interview yesterday. As the rover leaves Low Ridge, it will look back for one final examination of its own winter pad, "the ground under its body and wheels," he added.

Spirit will keep to the plan made months ago, stopping first at a rock just a few meters away, then heading back to Home Plate, the formation that science team members believe may be the remnant of an explosive volcano. After that, the rover may head southeast, lured by a bounty of new unusual rocks and formations the MER team can see in an image recently sent down from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera, an image that is a lot like the one released of Opportunity last month. Although the entire image of the Gusev crater site has not been officially released yet, the MER team was given the section that shows Spirit and some of the immediate surrounding area. All thumbs are way up as far as the early reviews go. "It's spectacular," Arvidson said, "and is already impacting our thoughts about where to go after Home Plate."

"In some respects, I think the [HiRISE image of] Spirit is almost better [than the Opportunity images]," offered Steve Squyres, the principal investigator for rover science and a professor of astronomy at Cornell University. "The lander is beautifully shown. The image of the backshell and the parachute is stunning -- you can actually see wrinkles in the parachute fabric and the backshell clearly landed right side up. The heat shield is very hard to see, but the rover you can see quite clearly. Husband Hill is spectacular. Bonneville crater is spectacular. You can see Home Plate and stuff around it that wasn't evident before, and it really is already dramatically affecting our planning," he added during an interview today. The image -- for which Squyres, also a member of the HiRISE team, is writing the caption -- is huge and due to be released soon. "It's more than 800 megabytes -- just gigantic," he noted. "We'll get the image out as soon as we can. We're just kind of drowning right now." Happily drowning, that is, in exquisitely-detailed images that would have been beyond any Martian explorer's dreams just 10 years ago.

On the other side of the planet, Opportunity completed its investigation of Cape Verde, where it spent superior conjunction, and began a northeast trek, clockwise, around Victoria crater toward the next promontory, Cape St. Mary. There, the rover turned back to take pictures of the other side of Cape Verde. As Americans were recuperating from the annual Thanksgiving stomach stuffing, Opportunity moved on toward the next vista location, Bahia sin Fondo (Bottomless Bay), logging a strong 43-meter drive last weekend. The team hasn't decided how far around the rim the rover will go in this direction, but, "it seems clear that some of the most intriguing geology we can see from the rim is to be found that way, so we'll go this way for awhile, driving from one lookout on the rim to the next, taking spectacular PanCam images of cliff faces," Squyres announced in his report on the Athena website.

Superior conjunction -- the astronomical event that occurs every 26 months when Mars orbits behind the Sun, out of sight from the Earth -- makes communication between teams on Earth and their spacecraft all but impossible for about 2 weeks because the lack of a direct line of sight between the 2 planets can severely corrupt radio commands; consequently, both rovers worked in "autopilot" mode the last 2 weeks in October, storing most of their research onboard.

Despite the preprogrammed schedule last month, the MER twins, true to form, managed to log another couple of significant milestones and both came through superior conjunction in "excellent health," Squyres said. Although no one on the MER team had been too concerned about the rovers coming through conjunction, Squyres summed it up for everyone when he said: "It was good to hear from them again."

If, however, October was slow, November has been anything but. Back "online," the twin robot field geologists jumped into the month with all wheels, literally, and got back to more demanding schedules. Among the first tasks -- downloading as much of their stored data files as possible. Spirit and Opportunity, however, had some real competition lately for access to the Deep Space Network (DSN), the international network of radio antennas that is used by interplanetary missions and astronomy observations exploring the solar system and the universe, as well as Earth-orbiting missions.

"We've been really data-starved over the last couple of weeks, because of restrictions on our downlinks," said Bruce Banerdt, MER Project Scientist, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers are being managed. With new demands on its time from MRO and unplanned searches for Mars Global Surveyor (MGS), which went suddenly silent on November 5, not to mention other ongoing missions, the DSN was booked solid in November. "We have been trying to squeeze down PanCam images -- we don't even have all of the Victoria pan from Cape Verde," he added. Waiting, it is said, is the hardest part and in this case, the waiting, Banerdt said, has been "painful."

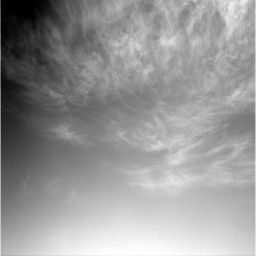

Clouds over Meridiani Planum

Clouds over Meridiani PlanumOpportunity took these pictures of clouds passing over Victoria crater with its navigation camera on Sol 950 (Sept. 25, 2006), as part of its daily science research. Both rovers continued searching the Martian sky for clouds during the superior conjunction.

Credit: Courtesy of NASA / JPL-Caltech

Even so, Spirit and Opportunity are roving ever onward and remain in amazingly good condition. All instruments that have been working are still working, although some are continuing to show obvious signs of age. The radioactive core of the Mössbauer spectrometer is decaying as expected. Still, the device, like the mini-thermal emission spectrometer (mini-TES), has defied all expectations and continued to function 10 times longer than its designed lifetime. The longevity, however, has come with a price: age has slowed it down and the Mössbauer now needs as much as 10 times the amount of time to get a good reading, give or take, depending on the iron content. That means the decision to use the instrument these days is a real commitment.

"We have to choose our targets very carefully," Arvidson said. "Since we're 10 times beyond the primary mission in terms of lifetime, no one is sure how long the Mössbauers can last. Although the systems look good, we're down so much in terms of cobalt 57 and the number of gamma rays given off that it takes 5 to 10 times the integration time now," he confirmed.

At the same time, the solar-powered rovers continue to gain energy as the Sun rises higher in the spring sky at Mars, with Spirit averaging around 320 watt hours this month and Opportunity, around 520 watt hours. Even with the onset of spring, though, the power levels won't likely rise dramatically anytime soon, because the dust season is about to blow in. "Based on historical experience, we expect the dust in the atmosphere to increase substantially soon," said Banerdt. "We are seeing a little increase now, but we don't expect the power in the solar panels to go up as quickly because of that."

Despite the swirling dust devils and the potential for menacing regional dust storms that could really darken the rovers' doorsteps, the MER team believes both Spirit and Opportunity are "in pretty good shape for survival," Squyres said. "Clearly if we get hit by a massive dust storm with a tau of 5 all bets are off," he clarified. [A tau of 5 would mean enough dust was kicked up to blot out the Sun.] "But if we see [dust storm] behavior comparable to what we saw last year I think we'll be in pretty good shape."

Dust devils in Gusev crater, sol 568

Dust devils in Gusev crater, sol 568Several dust devils are visible in this frame from a movie captured by Spirit on its Sol 568. Dust devils were observed frequently in Gusev as spring came to the rover'slanding site. Dust devil movies are available on Mark Lemmon's website.Credit: Courtesy NASA / JPL / Texas A&M

Spirit from Gusev Crater

November marked the beginning of the end of Spirit's almost 7-month stay at Low Ridge, its winter haven near the base of McCool Hill in the Columbia Hills region of Gusev crater. After a long, productive winter of working form one position, the much-anticipated first turns and moves of the rover this month signaled that it was entering the final phase of its winter science campaign there.

Throughout the month, Spirit performed its daily atmospheric and remote sensing observations, checking atmospheric clarity by taking "tau" measurements with its panoramic camera (PanCam), using its miniature thermal emission spectrometer (mini-TES) instrument take readings from the sky and ground, and looking for clouds with the navigation camera.

Spirit spent its work sols the first week of November using the mini-TES to check out some Martian dust, the PanCam to take pictures, one more time, of El Dorado, the rippled sand dune, as well as images of Martian sunsets, skies, and horizons. The rover also put the microscopic imager (MI) to use, taking extreme close-ups of its magnet array and a solar panel, as well as some pictures of targets Palmer and Mawson. And, it also began to use the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) for the first time in a while, on a target called Argon. The rover also continued its habit of multi-tasking during the communication window with Mars Odyssey, where it uplinks its images and data for the orbiter to relay to the DSN. Most of the time, it used this time to conduct its mini-TES research on the sky and ground, but it also checked out a target dubbed Casey Station during one pass in the first week of the month.

"We've done several measurements in closing off the winter science campaign," offered Arvidson by way of review. "First, we did MIs of clasts, these small rocks and small pebbles that were within the work volume. A lot of the rocks we've looked at in the Columbia Hills are granular, meaning that they look to be made of grains. In fact, Home Plate could be an eroded down, explosive volcano, so we might be looking at cemented ash from that, for example," he explained. "We're not sure -- it's still a work in progress, but that's why we wanted to take some MIs of these clasts."

By the end of its worksol on Sol 1010 (November 5, 2006), Spirit had finally completed everything it was going to do from its long-held position in its winter digs at Low Ridge and finally had acquired the 320 watt hours of power that satisfied the engineers it could move safely, without jeopardizing the position of its solar arrays to the Sun. Since the rover hadn't moved in nearly 7 months the power boost to 320 watt hours from an average low of around 275 watt hours was, as Jake Matijevic, engineering team chief for MER at JPL put it, "really a geometry effect with the Sun and Mars." In any case, the time finally arrived for Spirit to move.

Bright white stuff in Spirit's tracks

As Spirit headed eastward toward a hoped-for winter haven on McCool hill on Sol 788 (March 22, 2006), its wheels stirred up an unusually large quantity of bright-colored, presumably salty soil. For the full-resolution image, visit the Planetary Photojournal. Several days earlier, the rover's wheels unearthed a small patch of light-toned material dubbed Tyrone. In images from its PanCam, Tyrone strongly resembled both Arad and Paso Robles, two patches of light-toned soils discovered earlier in the mission. Spirit found Paso Robles in 2005 while climbing Cumberland Ridge on the western slope of Husband Hill, and the rover discovered Arad on the basin floor just south of Husband Hill in early January 2006. The rover's instruments confirmed that those soils had a salty chemistry dominated by iron-bearing sulfates, and the latest measurements taken of the whie stuff in the rover's tracks at Low Ridge also reveal a high sulfate content.

Credit: Courtesy NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

There really hasn't been a comparable period where Spirit or Opportunity haven't driven or moved for such a long period of time -- other than their almost 7-month flight to the planet, but they didn't have 3 years of Mars exploration under their "fanbelts" then either. So, there was a kind of obligatory concern about whether Spirit would easily pick up where it left off, so to speak, Matijevic said. An actuator [motor] or two could fail, but the rovers' history and the mechanics of their design made that seem "unlikely," he noted.

"Everybody immediately draws the analogy to their car -- and if you left your car parked in your driveway for a year and never started it and then tried to start it, it might not start because the battery might have died or it might not drive because some lubrication in some vital parts might have leaked or dried out, or metal parts somewhere may have rusted," said Squyres. "But Spirit and Opportunity aren't like your car and none of those things happen on our rovers. They are in a very dry environment, using electric motors and lubricants that are intended to be storable for long periods of time," he explained.

In fact, Squyres said, the team "looked hard" at the possibilities that Spirit might not move after winter passed. "We consulted all the experts on every piece of the rover and nobody could come up with a single credible mechanism that would cause the ability of the rover to drive to suddenly go away as a consequence of sitting in one place for a long time." Nobody, he added, could come up with "a single reason" as to why it wouldn't move again. Still, the rover had not moved its body in 204 sols.

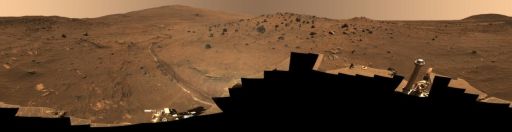

McMurdo Panorama released on Spirit's 1,000th Sol

McMurdo Panorama released on Spirit's 1,000th SolSpirit took this 360-degree view, called the McMurdo panorama with its panoramic camera (PanCam). October 26, 2006 marked Spirit's 1,000th Sol of what was planned as a 90-sol mission. The panorama was released to celebrate this milestone. It was produced from the most detailed imaging yet completed by either Spirit or its twin, Opportunity. Spirit began using the PanCam to shoot component images of this picture on Sol 814 (April 18, 2006) and completed the part shown here onSsol 932 (August 17, 2006). The overall panorama consists of 1,449 Pancam images and represents a raw data volume of nearly 500 megabytes. It is thus the largest, highest-fidelity view of Mars acquired from either rover. Very high resolution versions of this image are available at JPL's Planetary Photojournal.

Credit: Courtesy NASA / JPL / Cornell

Since the next chosen targets were quite near, Spirit's first move, as planned many weeks ago, was small -- just a "bump," as the MER team has come to define short moves. It was a simple 33-degree turn and a 0.71-meter (28-inch) turn, just enough really to put Spirit's instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm within reach of the new, desired targets. Despite the fact it would have been a "big surprise" if something had gone wrong, there was, Squyres admitted, "a little bit of relief" when they saw all 5 of the rover's functioning wheels turn again. [Spirit's right front wheel began acting up in July 2004 and subsequently went out of any sort of reliable commission.] At the end of the sol, turning for Spirit was, one might say -- one small turn for a rover, but another giant accomplishment for an already legendary mission.

"The first experiment after the bump was to analyze the bright, white soil right in front of the rover in the work volume, soil that had been disturbed by the wheel as it carved or etched out tracks as we drove to the winter campaign site," Arvidson explained. Visible in the McMurdo panorama, the white soil -- and specific targets therein -- dubbed Berkner Island and Berkner Island 2 -- turned out to be very sulfur rich. But the Berkner Islands may not have been locally formed.

"It may be that the soil that was dragged in the wheel and was deposited along the way all the way back from Tyrone, the soil area 20-25 meters back that we had difficult navigating through earlier this year," said Arvidson. Still, there seems to be so much of the white stuff visible in the tracks in the panoramic image. One wheel was "80% buried" at one point at Tyrone, "so it was pretty full of material when we started out from there," reminded Banerdt. "The people who have looked at this most closely say they believe this material has just been spilling out of the wheel as we have dragged it along." It is "the working hypothesis.", affirmed Squyres.

On Sol 1011 (November 6, 2006), Spirit performed a coordinated test with the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) to characterize the performance of the orbiter's UHF Electra radio. [MRO will provide data relay services for NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander, scheduled to arrive at Mars in May 2008.] Electra initiated the relay session by hailing Spirit, which responded with its own relay radio, and the 2 spacecraft established a link at 8 kilobits per second on the forward link, from MRO to Spirit, and 128 kilobits per second from Spirit back to the orbiter. Both radios used a communications standard called the Proximity-1 Space Link Protocol, established by the international Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems for ensuring compatible and gap-free communications on such relay links. In the 4-minute session, the orbiter delivered 5 commands to the rover, and the rover sent up 30 megabits of information, which the orbiter subsequently transmitted to Earth via the DSN. With the link established, the test was a success and Spirit finished out the first week of November by completing another panorama from its new position, which it began the sol before.

During the second week of the month, Spirit was consistently operating with a power level of 320 watt hours and was able to begin occasionally using the Mössbauer spectrometer or APXS overnight. On Sol 1013 (November 8, 2006) the rover used its front hazard avoidance cameras to look at the IDD work volume, then unstowed the MI and took a stereo picture of Berkner Island, and subsequently placed the APXS on Berkner Island 2 for 4 hours. That afternoon, when Odyssey passed overhead for the daily communications pass, the rover used its mini-TES to determine the mineralogical content of the target called Davis.

In the ensuing sols, Spirit changed tools, placing the Mössbauer spectrometer on Berkner Island 2 for 23 hours, measured the dust on its PanCam mast assembly -- its neck and head, then restarted the Mössbauer spectrometer on Berkner Island 2 for another, 10-hour integration, completing its daily atmospheric and remote sensing work around the Odyssey passes. On Sol 1016 (November 11, 2006), Spirit took some images with its navigation camera, and once again restarted the Mössbauer spectrometer on Berkner Island 2, this time for a 10-hour integration, for a final total integration time of 43 hours.

The rover then turned its IDD tools to another target of material exposed at the bottom of the rover tracks called Bear Island. "We put the instruments down in the bottom of the tracks where a little bit of outcrop was exposed, but there wasn't much so we don't even know if we got a really good signal from that," said Arvidson. The working hypothesis, Squyres added, "is that this stuff is basically ground up local outcrop."

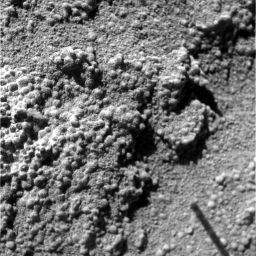

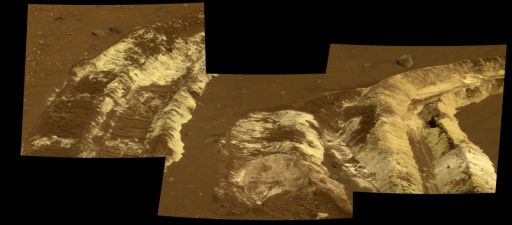

"Friable" materials encountered by Spirit

"Friable" materials encountered by SpiritThis raw image, which Spirit took with its PanCam, shows the "friable" or crumbly material that it investigated with its IDD instruments this month, where it investigateda specific target dubbed King George.Credit: Courtesy NASA / JPL

With those 2 investigations in its own tracks completed, Spirit made another move on Sol 1022 (November 17, 2006). "It was another bump, really a rotation about right front wheel, to position IDD instruments to get to the outcrop that was formerly off to the right of the vehicle at the winter science campaign," informed Arvidson. "We did a little drive, somewhat less than a meter that put us into position."

Right now, Spirit is examining a target on that outcrop. "We put the IDD down on the surface of a target we called King George and did APXS, Mössbauer spectrometer, and MI observations," Arvidson continued. We're in the process of brushing it with the rock abrasion tool (RAT) and then we'll repeat and finish those measurements this week," he said. King George is in the field of view from the McMurdo pan that shows the rover's tracks extending from front of the rover off to the horizon toward Tyrone. Just to the right, there is a little outcrop of "flakey, kind of friable [crumbly] looking stuff," Arvidson said, "and that's where our King George is."

Named for King George Island, the King George target on Mars was inspired by the change of seasons. "We're beginning to name features and targets after islands and other land forms in Antarctica going toward South America," Arvidson explained. "The idea is that we're done with the winter campaign and we're heading into the spring," he said.

Spirit positioned the IDD on top of part of that outcrop -- "not the flakey stuff because it wasn't strong enough," said Arvidson, but just above it. "We think that it's partly soil-covered outcrop, and we're in the process of brushing it and will put the MI, Mössbauer spectrometer, and APXS back on it to repeat the measurements with less soil."

The initial MI images are "real doozies," as Squyres describes them. "We still need to get good, uncontaminated APXS on that target, so I can't say what it's made of compositionally, but it appears to be one the best sorted, best rounded rocks we have seen anywhere," he noted.

Following the research at King Gerge, the plan is for Spirit to rove away from Low Ridge for good, driving first to a rock called Esperanza about 2 or 3 meters away, and then onto Home Plate, which is about 30 meters from where the rover is currently. As the rover takes its leave, it will do some final imaging and mini-TES observations of the winter science campaign site, including where the rover's wheels were, under the body of where the rover was, and all the IDD locations, said Arvidson. "We'll kind of look back and see if airflow around the rover during the winter resulted in any pattern of removal of dust or deposition of dust or what have you," expounded Squyres.

The MER team, not surprisingly, is anxious to get Spirit back on the road. "We're ready to go," confirmed Arvidson. "As soon as we finish the second sets of measurements on King George and then bump to take a look at where we've been since April, we're off to Esperanza, a rock that looks like vesicular basalt that may have formed from magma on top of a lava flow. Everybody's keen to see what the mineralogy and composition of it are. It's been mini-TESed many times from our current location and it's on the way to another outcrop (unnamed) that we want to measure before we go back to Home Plate."

That doesn't mean, however, that they aren't proud of Spirit's work at Low Ridge. "There's the whole record of the atmosphere over the winter campaign timeframe, still a work in progress because we're putting together the pressure-temperature profiles and distribution of clouds and everything else," said Arvidson. In addition, there are the data taken of the surface and looking for changes due to wind, which is also still a work in progress, he said. "Over the winter, Spirit really has been in a monitoring mode as opposed to a major discovery mode, but that is about to change."

Meanwhile, the team is still salivating over the HiRISE image of Spirit. "We can see a lot of the details in the Inner Basin and we're just beginning to use this image to relate back to the McMurdo panorama, so that we can put a stratigraphic or sedimentological framework into the measurements we did on the way to the winter science campaign site," Arvidson said.

If Spirit does head southeast from Home Plate, to some of the intriguing targets now visible in the HiRISE image, that means it will be going in the opposite direction of McCool Hill, where the team initially had planned for it to spend its second Martian winter. "We've had to give up the goal of going up the flank of McCool Hill because of the loss of the 6th wheel," said Banerdt. "Those slopes are just not in our repertoire anymore. The rover has become very sensitive to the material it’s driving on, so it's not completely predictable what you're going to be able to do in any given situation until you've determined just how loose or consolidated the ground you're driving over is. That makes any kind of extended drive pretty difficult."

With the information from the new HiRISE image though, that loss hardly seems to matter. "Probably the most spectacular thing of all in the image," noted Squyres, "is the stuff around Spirit right now." Moreover, added Arvidson, "between the McMurdo pan and the Hi-RISE frame, we can now really put together the whole stratigraphic pattern to see how Home Plate fits within that," The Hi-RISE image was just acquired a week ago last Wednesday, he noted. "I just saw it for the first time a couple of days ago, but you'll be pleasantly surprised. There's a lot of detail that's evident and you can see all the layers we've been looking at from the McMurdo pan."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

During the superior conjunction period from Opportunity's Sols 970 to sol 984 (October 16 to 30), this rover took some downtime from driving and, like its twin, went into autopilot. It devoted its conjunction agenda to collecting images for a Victoria crater panorama from the Cape Verde promontory, as well as collecting 3.5 hours of data each sol on the hole that the rover abraded with its rock abrasion tool (RAT) on the target Cha with the Mössbauer spectrometer.

Opportunity began November by finishing up work at Cape Verde. On Sol 986 (November 1, 2006), the rover took more images for the panorama, more Mössbauer readings of Cha, and began to re-transmit and delete data left in its flash memory from the superior conjunction. The rest of that first week, it devoted to finishing the Mössbauer work on Cha, checking out targets with the mini-TES, and conducting its daily atmospheric and remote sensing observations.

Both Opportunity and Spirit have and will continue to collect these data, taking "tau" measurements with the PanCam to assess atmospheric clarity, using the mini-TES to monitor any changes in the sky and on ground, and the navigation camera to look for clouds. "We try to run the same sequence each day, at roughly the same time of day each day, so that we get a nice, quantitative baseline that provides a continuous record of atmospheric conditions at both of the rover sites," explained Squyres. Ultimately, the data will reveal climate and wind patterns and impacts on the rovers' respective exploration sites, allowing scientists to better understand the mechanisms of the atmosphere of Mars.

By Sol 991 (November 6, 2006) Opportunity had completed the acquisition of the panorama and moved away from Cape Verde, roving into the second week of November by continuing its clockwise drive around the rim of Victoria to the next promontory, called Cape St. Mary, taking pictures along the way. During the first leg of the drive to St. Mary on Sol 992 (November 8, 2006), rover planners performed the first step of the new flight software checkout, specifically one of the rover's new drive technologies, called visual target tracking (VTT). This first checkout included picking a target for Opportunity to track and having the rover drive to that target to test its knowledge of how its position changed relative to the target. The checkout was a success. "The visual target tracking test went very well and everything worked just as planned," Banerdt said. "The analysis says the software is doing just what we want it to do."

In the following sols, Opportunity took more images of Victoria crater with the PanCam, and cruised along the rim road toward Cape St. Mary on Sol 999 (November 15, 2006), taking pictures of the other side of Cape Verde, the northeast-facing cliff, to better characterize the crater wall and scouting along the way for any other safe place to drive into the crater.

The MER science team members already know that Opportunity can enter the crater from Duck Bay, but that doesn't mean, they're planning right now to go into the crater. "We will make the decision about going in at some point in the future, but we definitely have a route that will get us in safely if we need to," he said. "Certainly, Duck Bay is a safe way in. Whether it's a safe way out or not, we haven't really done the analysis. But we don't want to get too far ahead of ourselves. We've got a lot of work to do along the rim first and that's our current focus."

The rover arrived in the vicinity of Cape St. Mary on Sol 1002 (November 18, 2006), and bumped to the desired position at a place dubbed St. Mary Point on Sol 1004 (November 20, 2006). Over the next 2 sols, Opportunity took breaks from its own work agenda to help in the search for Mars Global Surveyor, which has not been heard from since November 5. The rover tried to establish contact with the orbiter on both Sols 1005 and 1006, said Squyres, "but we didn't hear anything."

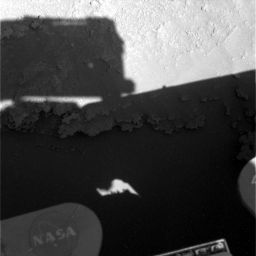

Opportunity's parachute as seen by HiRISE

Opportunity's parachute as seen by HiRISEThe bright irregularly-shaped feature in this image -- released yesterday, November 29, 2006, by the High Resolution Science Imaging Experiment (HiRISE) camera team from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) -- is Opportunity's parachute, now lying on the Martian surface. Near the parachute is the cone-shaped "backshell" that helped protect the lander during its 7-month journey to Mars. Dark surface material may have been disturbed when the backshell touched down, exposing the lighter-toned materials seen next to the backshell. Credit: NASA / JPL / Univ. of AZ

The silence that greeted Opportunity is not a "conclusive finding," Banerdt stressed. As it turns out, he added, "if the spacecraft is not nadir pointed, there is/was only a 1 in 6 chance of it picking up the signal." Statistically then, it was a little bit of a stretch. Even so, while everyone agrees it's not time to completely give up on MGS yet, everyone also acknowledges not hearing anything at this point is "not a good thing," as Banerdt put it.

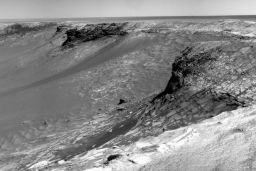

Opportunity spent Sol 1007 (November 23, 2006 or Thanksgiving Day) and most of the rest of the holiday taking pictures of Cape Verde and Victoria crater, and conducting remote sensing. "One of the things that has been most interesting in the image that we took of the other side of Cape Verde, which we shot from Cape St. Mary, is that it just spectacularly shows the stratigraphy in the ejecta from Victoria crater," said Squyres. "This is a very well-preserved slice through some impact crater ejecta on another planet and we're going to get a lot of interesting science out of this, having to do with impact cratering mechanics and ejecta transport and the physics of the interaction of impact-generated shockwaves with rock, and so forth."

After taking care of business at Cape St. Mary, Opportunity roved northeast around the rim again, logging a 43-meter drive toward the next promontory, called Bahia sin Fondo (Bottomless Bay), on Sol 1009 (November 25, 2006). This vista point could also be a way for Opportunity to drive into the crater, Squyres said. Another drive was scheduled for Sol 1012 (November 28, 2006), but it was slated to be a short 20-meter drive, because another module of the new flight software, called D*, had been scheduled for checkout.

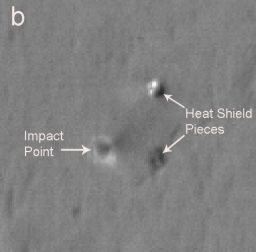

Opportunity's heat shield as seen by HiRISE

Opportunity's heat shield as seen by HiRISEThis image -- just released by the by MRO's High Resolution Science Imaging Experiment (HiRISE) camera team yesterday, November 29, 2006 -- shows the impact point and the broken remnants of Opportunity's heat shield, which protected the spacecraft during its fiery descent through the Martian atmosphere. The heat shield was released from the spacecraft during the final stages of the descent, breaking into two pieces when it hit the Martian surface. Also visible is the small crater formed at the heat shield's impact point. The rover visited its heat shield during a drive southward from Endurance crater.

Credit: Courtesy NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

"D-star is some of the advanced autonomous drive software," explained Banerdt. In the planned checkout, "the rover is given a waypoint to go to and along the way the software puts up a 'keep out' zone in front of the rover, so that Opportunity has to get around that zone safely and to the target on its own." As it turned out, Opportunity's data situation was "too tight," said Squyres, "so we planned a normal drive on Sol 1012 and postponed D-star to today."

Even so, a long drive just wasn't in the cards for Opportunity on Tuesday. "The Sol 1012 drive terminated early," Squyres informed, and the rover only advanced some 14 meters. "We're on very flat, very benign terrain with a tiny number of rocks, but standard operating procedure on flat ground is that we set things so that the drive will terminate if either of the bogey angles ever get to be bigger than 8 degrees, just as a safeguard in case something weird happens," Squyres elaborated. The safeguard works in both directions -- if the rover is going over a rock and tilts too much or if it drops into a void or hole and tilts too much as a result of that.

The rovers feature suspension systems that are comprised of rocker/bogey platforms. In this case, the bogey that holds Opportunity's 2 back wheels on one side hit the 8-degree limit when the rover encountered one of the few rocks on the landscape. This rover, of course, seems to have a way for doing such impossible things. Remember, it was the one that bounced to a landing right inside Eagle crater, making for "the world's first interplanetary hole-in-one," as Squyres jubilantly called it back in January 2004.

"Since we are on such flat terrain, we never expected this to happen, but we went across one of the few rocks in the area and it tilted that bogey enough for the rover to terminate the drive early," Squyres explained. All in all, it was "a benign event," he assessed. "You've got the software in there to stop you if something funny happens and it did its job."

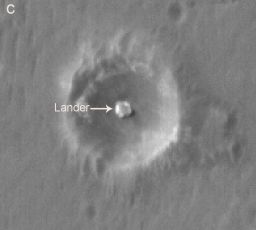

Opportunity's 300 million mile hole-in-one

Opportunity's 300 million mile hole-in-oneThis image -- just released yesterday, November 29, 2006, by the HiRISE camera team -- shows Eagle crater, the small Martian impact crater where Opportunity's airbag-cushioned lander came to rest -- the mission's 300-million-mile "hole in one." The lander, from which the rover rolled off, is still clearly visible on the floor of the crater. Opportunity spent about 60 Martian days exploring rock outcrops and soils in Eagle crater before setting off for Endurance crater to explore more of Meridiani Planum.

Credit: Courtesy NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

Opportunity was scheduled to drive again today -- Sol 1014 -- and the D* checkout was again on the agenda. [Later on, the rover handlers will direct the Opportunity to where there is an actual obstacle in the way and it will have to identify and avoid it, and then get to the target indicated was on the other side of this obstacle, all by itself, autonomously.]

At this point, the MER team has not named any other promontories or targets, Squyres said. "We're going to image both side of Bahia sin Fondo (Bottomless Bay), from the side we're coming in on, then loop around it and image it from the other side." The plan then, generally speaking, is for Opportunity to drive from one lookout or vista point on the rim of Victoria to the next, taking Pan Cam images of the cliff faces. So far, the rover's returns are "pretty spectacular," said Squyres.

"One of the things we were hoping to do is get a good look at the unit we saw very close to the base of Cape Verde -- around the first side when we first imaged it from Duck Bay -- the very evident, kind of well-bedded layer you could see deep down in the crater. We wanted to see how that wrapped around onto the other side and see if that got thicker or thinner or whatever. We're in the process of doing the geometric analysis on that right now to find the answer to that question now."

If the rover completes the planned 20-meter drive today, it will put it "at least halfway" to Bahia sin Fondo (Bottomless Bay)," Squyres said. "We'll plan another drive tomorrow [to take place on] the weekend and we should find ourselves getting close to the rim of Bottomless Bay by Monday."

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth