The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit "Bumps" a Move, Opportunity Puts the Pedal to the Metal

Written by

A.J.S. Rayl

Contributing Editor, The Planetary Society

October 31, 2008

Spring is still off a ways on the horizon in the Red Planet’s southern hemisphere, but the solar-powered Mars Exploration Rovers seemed to shake off their third Martian winter this month, as they roved into new phases and looked to new destinations on their overland expeditions of Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum. In the process, Spirit and Opportunity both chalked up notable achievements in October, adding to their already long list of accomplishments accrued as the world’s first long-lived roving robot field geologists.

"Spirit bumped," announced Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, principal investigator for rover science, in an interview earlier this week. The "bump" or short move was the first time this rover has moved from its stationary position just off the northern edge of Home Plate in nearly 8 months and Spirit performed flawlessly.

At Meridiani Planum, Opportunity is "ripping," Squyres said, as the rover prepared to take-off on another 100-meter drive on its journey to another, monster-sized crater dubbed Endeavour, located 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) away. It’s an ambitious objective to be sure. It’s taken Opportunity four and a half years to log its first 12 kilometers. In fact, it just crossed that milestone in September. No one’s sure the rover will make it to the really big crater. But no one is saying ‘never’ around this rover either.

“Last weekend, we did a 216-meter drive that fell short of our all-time record by just 4 meters," offered Squyres. That is, by any account, impressive.

When Spirit managed to "bump" or move slightly upward about 8 centimeters from its perch on Home Plate, a circular, eroded over volcanic formation, this power-challenged but ever courageous rover endeared the team and the hundreds of thousands of its human admirers around the world yet again. Sure, it's a move that's just a tad over 3 inches, but this rover hasn't moved its wheels since February.

"The distribution of energy on the wheels was a little bit skewed, because we're trying to use the back wheels to push the vehicle up, but otherwise Spirit had no issues," reported Jake Matijevic, chief of rover engineering at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where Spirit and Opportunity were designed, built, and are being managed. In the end, he summed up, “it was just very standard drive."

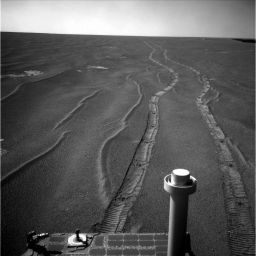

Movin' on up

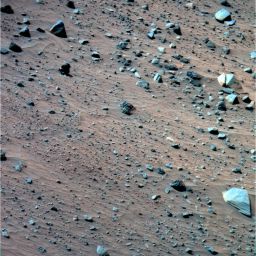

Movin' on upSpirit used its front hazard camera to take this raw image from its parked position off the northern edge of Home Plate. The rover "bumped" this month, moving for the first time in about 8 months, and it succeeded in moving up slope, just as the MER team wanted.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

After spending some 8 months perched off the northern edge of Home Plate at a 30-degree angle, Spirit is now parked at a 25-degree angle, a better position for the spring Sun. Changing its angle -- and thus the tilt of its solar arrays -- allows Spirit to take in more sunlight for fuel. Best of all, the rover bumped in the direction everyone had been hoping it would -- uphill.

"I felt real good about seeing the wheels turn and about actually making uphill progress when we were on a 30-degree slope," Squyres said. "We were successful in moving uphill, but I'm not yet prepared to say that we're going to make it up onto Home Plate.”

Spirit just as easily could have dug in or slipped given that its right front steering wheel is frozen and doesn't move. That handicap makes it"awkward to move forward," Matijevic reminded. "With the right front wheel the way it is, even though it is actually right on top of the lip of slope, you're really pushing against a dead weight there. What was encouraging about the bump is that we did move forward."

The team wants to direct Spirit back onto Home Plate so it can rove across the top toward its next, highly anticipated destinations, a mesa and non-circular hole in thee ground to the south, named for rocketeers Werner von Braun and Robert Goddard. "Right now we've got some reason to hope that we might be able to scratch our way back up onto Home Plate," said Squyres, "and if we can that will save us probably weeks in our drive toward von Braun and Goddard."

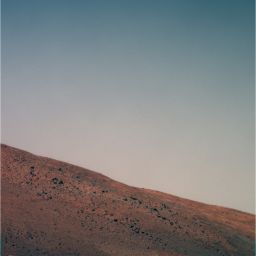

Spirit at Home

Spirit at HomeThis image shows Spirit at its current location on the northern edge of Home Plate in the Columbia Hills, Gusev Crater. The picture was taken during the southern hemisphere winter solstice at about 2 p.m. local time on the rover's Sol 1591 (June 24, 2008). Home Plate is the elevated round and light toned mesa on the right side of the image. Spirit is visible at the little dark "bump" on the north-northeast edge of the circular volcanic formation. Mid-winter on Mars is the time of the clearest and least dusty atmosphere.

Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

The first bump indicated that "it may actually work," Matijevic said, cautiously optimistic. Going over the top of Home Plate is not only the shortest route, since Spirit is hanging off the northern edge, it offers a somewhat "more predictable drive," he added. If the rover can't go across the top of Home Plate, it will have to back down the volcanic plateau and go around to head south.

In the sols before its big little move this month, Spirit completed taking the more than 2,000 pictures that will be used to produce its third winter panorama, a 360-degree masterpiece mosaic named for Chesley Bonestell, the late, great, much-loved space artist. "Bonestell is finished," confirmed panoramic camera (Pancam) lead scientist Jim Bell, of Cornell University, who, actually, is the new President of The Planetary Society. But a lot of images are still on the rover, stored temporarily in its flash memory. “Downlink is slow -- power is still pretty low,” he explained. “We have to be patient.” The Pancam images are not the only science data holed up in Spirit’s flash.

With winter fading and the temperature at Gusev Crater slowly rising, the rover was able to use power to conduct science instead of expending it all on heaters to stay alive. This month, for the first time in many months, Spirit pointed its miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) at surface targets dubbed Gernsback, Jules Verne, and Stapledon, located “down below and behind the rover” and potentially brimming with silica, according to Steve Ruff, of Arizona State University, lead Mini-TES scientist.

Jim Bell

Jim BellAn Associate Professor in the Cornell University Astronomy Department, Bell is the lead scientist for the Pancam color imaging system on the Spirit and Opportunity. He is also the new president of The Planetary Society. Credit: Cornell University

Spirit’s discovery of near pure silica is one of the MER mission’s most significant finds and the science team is anxious to find more. The Mini-TES is a highly sensitive instrument that allows the roversto analyze the composition of a target from a distance, delineating minerals and compounds present by reading its thermal signatures. While the instrument was kept warm through the beyond brutally cold Martian winter nights and was able to survive the season, its optics are still so dusty from the global dust storm of 2007 that getting a solid reading on any of the targets this month was next to impossible.

“Each of these targets is a candidate for the same kind of silica-rich, nodular-like outcrops that we saw in abundance in the East Valley,” aka Silica Valley,” Ruff said. “But I'm waiting for the color Pancam frames to support [the notion] or not.”

It shouldn’t be much longer, said Matijevic. Both Spirit and Opportunity are downlinking data every day to free up flash memory space in preparation for solar conjunction, a two-week time period when the Earth and Mars are on opposite sides of the Sun and communications between the two planets are blocked.

The solar conjunction begins at the end of November, so the team has charged the rovers with getting all recent images and science observations home so there will be plenty of room to store the data collected during the solar conjunction.

"Since the beginning of October, we have basically been doing communications sessions every day," Matijevic informed. "We're slowly chipping away on the data that's now onboard."

At the same time, Spirit and crew are amping up to rove onward. "We'll probably bump some more," said Squyres. The engineers would like to move the rover, angel its solar arrays to 20 degrees, added Matijevic. So when the power is right in coming sols, Spirit will undoubtedly be movin’ on – up, hopefully.

On the other side of the Red Planet, at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity spent October bidding a final farewell to Victoria Crater, its home for the past two Earth years. Before it left it took some stereo Pancam images of Cape Pillar and Cape Victory, as well as some parting shots of the crater.

Then, it made some serious tracks, setting its second longest one-sol-drive record with the 216-meter drive last weekend, on Sol 1690. "We've left Victoria for good," Squyres said in an interview this week. The longest drive ever was 220 meters on Sol 410, "a little ways south of Endurance and toward Victoria," recalled Squyres. "That was a long time ago and the terrain there was much easier than the terrain we're driving in now."

The plan is to head southwest “to intersect some terrain that has a fair amount of pavement-like outcrop on it,” Squyres said. Expounded Matijevic: "This area [which has not yet been named] is about a kilometer or kilometer and a half south of Victoria and we're moving pretty well along the rim of the crater down towards that outcrop." From that point, said Squyres, "we'll just follow the yellow brick road to the south."

As Opportunity made tracks in October, it continued -- and will continue in November -- to search for an appropriate cobble to study up close. "We've been keeping our eyes open and every day we look around for a cobble to look at," Squyres said. The team would like to find one on which the rover can place its instrument deployment device (IDD) during solar conjunction, he noted.

Since Opportunity’s next destination is so far away, this rover’s mission for now is really mostly about driving while the driving is good. The yellow brick road at Meridiani is paved, after all, with ripples. Some of the ripples are moderate size, about 10 centimeters tall, and some are larger, more in the range of 35 centimeters, more like the size of Purgatory Dune, which snared Opportunity back in April 2005 and held it prisoner for 6 weeks. They’re so reminiscent actually the team has generically dubbed these larger ripples as purgatoids. "We're starting to see some purgatoids,” said Squyres, “and we're being real careful to avoid those."

The MER team has been using orbital images taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) to chart routes for both rovers, and especially to plan the long-distance roadmap for Opportunity's epic trek to Endeavour.

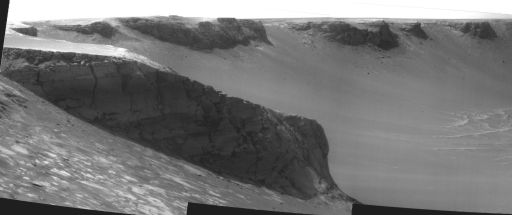

Onward

OnwardOpportunity put the pedal to the metal this month and left Victoria Crater, its home for the past 2 years, for good. It's been making regular 100+-meter drives and last weekend nearly broke its own record when it logged a 216-meter drive. This image, which the rover took with its Pancam was enhanced with humor by Stuart Atkinson.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Stuart Atkinson

"We've had to go a little bit out of our way with Opportunity, but we have generally been traversing fairly well," said Matijevic. Even so, he added, "the path we sort of picked to the new crater goes around some of these obstacles, the purgatoids, and probably means we'll be driving more like a total of 18 kilometers to get to the edge of Endeavour."

Along the way, Opportunity, like Spirit, is downlinking daily these days to free up space in the flash memory for the data collected during solar conjunction. And, as with Spirit, a lot of that accumulated data are Pancam images. "We are still downlinking some older Pancam data from the last two capes," noted Bell. "Again, we have to be patient as the downlink trickles in. Sometimes it can be frustrating to have to wait, however. If only we had a faster interplanetary internet connection."

Both Spirit and Opportunity remain in remarkably good health, though each lost a little energy this month as the tau – or the amount of dust in the skies over both Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum – increased. "We've been seeing some tau fluctuations recently that have had some impact on the power levels," confirmed Squyres. The increase and fluctuation in dust come with the Martian spring and so were expected. But by comparison to the last two spring seasons the rovers have experienced, this one, for now, appears fairly mild, with less dust in the atmosphere than might be expected.

Spirit's already low power level of around 255 watt-hours at the top of the month, however, dropped to a low of 215 watt-hours this week. Although its much-anticipated bump was successful, at the same time the tilt changed, the rover saw the increase in dust in the skies. “That has more than offset the benefits from the tilt," Squyres said.

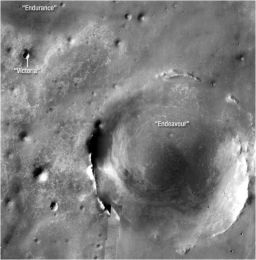

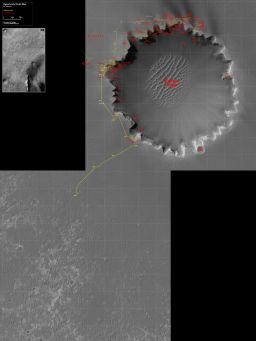

Opportunity's next big destination

Opportunity's next big destinationThe MER team has chosen a a crater more than 20 times wider than Victoria Crater as Opportunity's next destination. The rover began the long, 12-kilometer (about 7.5-mile) journey -- which p.i. Steve Squyres estimates will take about 2 years, with science stops along the way -- on Friday, Sep. 26, 2008 with a 152-meter drive. The crater, which is to the southeast of Opportunity's location at Victoria, dominates this orbital view from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera onbaord Mars Odyssey orbiter. Victoria is the most prominent circle near the upper left corner of the image. This view is a mosaic of about 50 separate visible-light images.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASU

"The rover moved from a 30-degree angle to a 25-degree angle,” said Matijevic. “The bump was really just a small angular correction, so we didn’t really expect a big jump in power levels.” The paltry 215 watt-hours, however, sounds frighteningly low for rover followers. “But that is a temporary thing,” Squyres reminded, “because the tau fluctuates.”

Even so, there’s hope and fear on the trail as Spirit's solar panels continue taking on the powdery rust-red dust that is everywhere on Mars. Somehow, 32% of the sunlight is still getting through the dusty arrays, Matijevic said, so the rover has ample power to keep on keepin’ on for now. Unlike its twin, Spirit has yet to be graced by any of Mars' helpful little wind gusts and hope floats on high for that. "We're hoping,” said Squyres, “Mars will be kind to us one of these days.”

They’re hoping, too, it will be kind to the rovers’ Mini-TESes. The dust that enveloped the rovers in a global storm in June-July 2007 infiltrated the optics on Spirit’s Mini-TES, just as it did on Opportunity’s, only not quite as bad. Where Opportunity’s instrument is “blind,” Spirit’s Mini-TES is “legally impaired,” as Ruff has defined it.

“Only about 15% of the thermal infrared light from the scene – surface or sky – is making it to the detector,” said Ruff. Although the instrument has gotten some useable readings from strong elements like carbon dioxide in atmospheric studies, “that's often not the case for the surface targets where the spectral features we're looking for are much more subtle,” he explained. “Those tend to be obscured by the contaminated optics. It's not looking very hopeful at this point, but we're still trying to use this instrument to do science on the gound. We're not ready to give up.”

In fact, the MER team has yet to give up on Opportunity’s Mini-TES, which was completely dusted in the global storm of 2007 and is, at the moment, scientifically useless. “There is no throughput of infrared energy on that instrument,” Ruff said. This month, however, rover planners commanded to do "the Mini-TES mirror shake," as Squyres described it. It was a trick they learned by accident, back during testing, before launch.

“At one point excess voltage was applied to the Mini-TES pointing mirror in the Pancam mast and it vibrated the thing, more than an engineer would like,” recounted Ruff. “When a mechanism starts sort of buzzing and it's not supposed to, well, that's not a good thing. Anyway, we found out then we could overdrive the motor for that pointing mirror and cause this vibration.”

The thinking is, maybe the vibration will loosen some of the dust obscuring the optics. After a lot of testing with the rover in JPL’s Mars Yard here on Earth, the MER engineers deemed it safe and agreed to do it. "It was just a 3-second test to see if it behaved the way it did in the test bed and it behaved exactly the way it did in the test bed," said Squyres. "No one expected a big cloud of dust and all of a sudden we're going to see clearly again, but we now know we can do this vibration of the mirror on Mars now and we're going to try to actually do a fairly, more aggressive real shake to try and clear some dust off probably sometime next week."

“If the vibration approach doesn't work we may just decide to go with Plan B, opening up the Mini-TES mirror to the outside and leave it parked there,” added Ruff. “Typically, Mini-TES does its observations, then closes up so that it's shielded from direct winds and dust and whatnot from Mars. Ironically, those cameras onboard that have been exposed continually – like the hazard cameras and even Pancam sometimes -- seem to stay relatively clean. Despite their build-ups, they tend to get cleaned off from time to time, so maybe we can get the same effect on Mini-TES.”

Opportunity, which has been power-rich throughout the rovers' third Martian winter, experienced a drop in power levels, just like Spirit, as a result of dustier skies overhead. From a high hovering around 655 watt-hours, the rover’s power production fell to 560 watt-hours this week. [For comparison, when the rovers landed in January 2004 they were producing around 900-950 watt-hours of power.]

"To some extent this may be just an accumulation of dust on the array," Matijevic assessed. "We moved from an area that seemed to have the benefit of the Martian winds blowing material off the solar panel and we've been accumulating more dust here. Opportunity is still very healthy."

Perhaps the most significant news as far as Opportunity's monthly physical goes is that there has been no repeat of the current spike that the rover experienced with its left front wheel motor, according to Matijevic. “None.” All six wheels are turning fine.

With the passing of another month – the 58th since the mission began – Spirit and Opportunity – are performing beautifully, ready, willing, and still very much able it appears to further push the boundaries of their explorations of Mars' Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum.

Spirit from Gusev Crater

Spirit began the month of October carrying out the same basic science agenda that it's had for the last several months, monitoring the dust in the atmosphere and taking the rest of the some 2,000 pictures that will be mosaicked into its third 360-degree, full color winter panorama. Only unlike the last several months, it was sporting a decent amount of power, with levels hovering around 255 watt-hours.

Since January, this rover has been parked just off the northern edge of Home Plate, a circular, eroded-over volcanic formation, surrounded by an area that last year offered up some of the mission's grandest riches in the form of nearly pure silica. The Bonestell Pan will reveal the haven in which Spirit has been residing for nearly 8 months in all its Martian glory. It was expected to be so spectacular that the team decided to name it after famed space artist Chesley Bonestell.

Half a Bonestell Pan

Half a Bonestell PanAlthough the chill and low sun of winter sharply limited the science activity of Spirit, the rover slowly and steadily acquired more than 2,000 images for its thrid 360-degree winter panorama, taken this season from its parking spot just off the northern slope of Home Plate. This image represents about 120 sols of work for the rover. The rest will be processed in coming weeks as all the images come down from Mars. This panorama was taken from the Martian Chronicles weblog, where it can be downloaded at its original resolution; the color in the version shown here has been tweaked slightly by Astro0.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell

With its newfound energy, Spirit was not only able to finish the Bonestell Panorama in the first week of October, but it was also able to take two super-resolution images of targets in the Home Plate realm with the panoramic camera (Pancam). These select, super-res frames of targets -- named General B.O. Davis and Hercules Joyner, in honor of two if the Tuskegee Airmen who served and earned renown in World War II -- will be incorporated into the Bonestell Pan, and allow for more detailed studies of those areas.

In addition, Spirit completed a routine atmospheric measurement of argon gas with its alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), something that helps scientists characterize seasonal airflows between the Martian poles, and took some four-frame time-lapse "movies" in search of clouds with its navigation camera. Both rovers, actually, have been taking these little "movies" so that scientists can study the Martian atmosphere, and usually they are comprised of six frames.

Steve Ruff

Steve RuffThe lead scientist on the miniature thermal emission spectrometer, better known as the Mini-TES, Ruff is a Faculty Research Associate at Arizona State University, working in the School of Earth and Space Exploration's Mars Space Flight Facility. Credit: Arizona State University

"There are adjustable parameters for the observation," Matijevic said. "It makes more sense to think of it in terms of how long we actually stare at the sky. A routine observation is to look for about 20 minutes and in that period you will acquire about 6 frames of images,” he explained. “What we usually do is look at thumbnails, which are 1-kilobit versions of the picture and determine from those whether or not a cloud was actually present in the image. That way, we can reprioritize the images.” Hence, the four- frame movies basically indicate that Spirit stared at the sky for about 15 minutes, rather than 20 minutes.

Spirit wrapped the first week of the month by spending a sol using its miniature thermal-emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) for the first time in a long time to check out Gernsback, a gravelly patch located behind and below the rover. Although the team has used the instrument to check out the sky and ground periodically throughout the last couple of months, power limitations prevented it from being used on ground targets.

"The ability to use the Mini-TES is a consequence of the fact that we're able to generate a little more energy onboard the vehicle," offered Matijevic. "A Mini-TES observation takes about 15 minutes or so to accomplish and we haven't really had 15 or 20 minutes to devote to science observations during the long winter.”

Gernsback is tantalizing, according to Mini-TES lead scientist, Steve Ruff, of Arizona State University. It “looks like the silica-rich, nodular outcrops” that the rover found in abundance East or Silica Valley, he said during an interview this week. But what before the global dust storm of 2007 would have been simple now has turned difficult, and the ASU faculty research associate can’t tell yet if any silica is actually hiding there or not.

Gernsback

GernsbackSpirit used its miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) on several surface targets this month, one of which can be seen toward the middle left portion of this Pancam false color image. "The majority of rocks and gravel in this scene look blue gray, but on the left side, mid-way there is a gravelly patch that has a more reddish color to it," said Steve Ruff, the lead scientist for the instrument. "This was the first inkling that I had, based on the Pancam image, that there might be more of this silica rich material that we found last year in the East Valley, also known as Silica Valley."

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell

“Unfortunately, the main pointing mirror is very heavily covered in dust and obscures most of what we can see,” Ruff said. Dust, actually, is blocking 85% of the thermal infrared light, which the instrument uses to analyze composition.

“Those are some dirty eyeglasses that we're looking through, so it's hard to make out the details of what we're looking for,” Ruff expounded. “I haven't come up with anything that's a positive result that says, ‘oh sure, we're seeing more of the same.' That could mean one of two things – either this is stuff isn't more high silica material or the mirror dust is so thick and so disruptive to the spectra that I just can't see the features that I need to see. Either one of those could be true.”

If Opportunity is able to get the “Mini-TES shake” to work, the MER team will have Spirit try it, Ruff said. “Spirit’s Mini-TES is not completely blind, but it is legally impaired,” he said. “If we have success on Opportunity, we'll try it on Spirit.”

If vibrating the Mini-TES mirrors doesn’t work, the MER team has another trick, at least in theory, a “Plan B,” Ruff said. And it’s simple. “Open the Mini-TES mirror to the outside and hope magically the instruments’ optics get cleaned off like other cameras have been.” In other words, leave the instrument open and its optics exposed to the elements and hope Mars sends a gust of wind to blow away the dust.

Finding more silica is something of a priority for this rover. “The discovery of near pure silica in the East Valley [Silica Valley] region is not limited to that disturbed track that we made,” said Ruff. “There are dozens of what we've been calling nodule like outcrops that Mini-TES and APXS see high silica in as well. Most of the world thinks we just trenched and found this white soil and that was the end of the story. But there's a much larger story in the form of these outcrops and as we continue on our exploration, we're going to be on the lookout for more of them,” he noted.

To have that kind of confidence and not be able to prove it unequivocally is “frustrating,” Ruff admitted. “Under normal circumstances, this is exactly what Mini-TES is great for – from a distance -- without touching the target -- we could tell if we're seeing more of it. Then again, it's hard to get too frustrated with a mission that's now approaching 5 years,” he added. “It's a marvel and we certainly have had success using the Min-TES, especially at Gusev to make the discovery of near pure silica.” That acknowledged, “no one,” he reiterated, “is giving up.”

Past being able to add more science into its agenda, Spirit was able to begin "phoning" home more often in October and as the first week of the month got underway, the engineers on Earth were adapting their schedules to reach out more frequently.

The rovers stay in touch with their ground team by transmitting data at UHF frequencies to the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which in turn downlinks it to the Deep Space Network (DSN) on Earth. From the Earth, engineers uplink new activity plans to Spirit and Opportunity using X-band radio transmissions that go directly to the rovers' dish or high-gain antenna.

More frequent communication with Spirit this month allowed for the greater operational flexibility needed as it transitioned from a reduced-operations winter mode to a more normal planning schedule that included moving for the first time in more some 8 months.

Traditionally throughout the MER mission, rover operators have relied on "beeps" – short X-band transmissions sent to Earth over Spirit's low-gain antenna -- to know if it received and activated command sequences that were sent up. As power levels sank in the depth of this past Martian winter, however, engineers discontinued the beeps to save energy. In October, they reinitiated the beeping program, but the signal strength from Spirit's low-gain antenna was not good enough for the MER team on Earth to hear. Engineers at JPL decided to have the rover send a few beeps through its dish-shaped, high-gain antenna. "That did the trick," Matijevic said, and robot and humans had each other at beep once again.

Spirit from on HiRISE

Spirit from on HiRISEMore than a year of Spirit's examination of the feature in Gusev Crater known as Home Plate is chronicled in this animation of nine images from the HiRISE camera on MRO. The images cover an area approximately 100 meters square. The geometry of Home Plate appears to shift from image to image because the orbiter often had to turn to one side or the other of its orbital track across Mars in order to view Spirit, so usually saw the raised topography of Home Plate from a point that was not directly over Spirit's head. However, some of the apparent shifts in features are also real shifts in the distribution of dust around Home Plate with shifting winds and seasons. The global dust storm of summer 2007 almost completely blocks the view of Spirit at one point during the animation.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / Doug Ellison

All NASA’s success at Mars does have, believe it or not, a downside for many of the missed communications with the rovers are because of other missions at Mars. There is a lot of traffic on the airwaves these days between Earth and Mars, from and between Mars Odyssey, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, and Phoenix. “These days, it’s always a matter of trying to overcome the background noise produced MRO,” said Matijevic. The beeps, fortunately enough, came through loud and clear through Spirit’s high gain antenna.

The MER team also uses beeps to get a rough estimate of the time drift in the rover's clock during the past nine months or so. Just like your wristwatch falls out of sync with real time, "timing beeps" sent to Spirit this month showed that its clock had drifted 40 to 50 seconds from Earth time, Matijevic informed. "We scheduled a direct-to-Earth transmission last weekend. When we do that we send 'time packets,' which are basically a more precise way of being able to measure the receipt time of the signal at the ground control station. The actual spacecraft clock time is in the packet that is sent and the contrast between that and the actual receipt of the packet back at the DSN becomes the mechanism by which we are able to do a time differential," he explained. "We take into account the one-way light time difference and what's left is the drift in the clock."

As the second week of October took hold, Spirit pointed its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) to the sky to take more routine measurements of atmospheric argon. "A lot of the rover's energy that had gone to survival heating was devoted to doing science investigations this month,” said Matijevic. "The fact that the Sun is kind of moving back towards the south and that the environment is starting to warm up is really making a difference.” There is, however, a tradeoff.

By putting most of its available power into science activities, Spirit has not had the energy necessary for sending all that data home and its flash memory began getting pretty full. In fact, at the top of the month, Spirit only had around 300 megabits of empty space. It was an issue with the flash that sent Spirit into a tailspin shortly after landing in January 2004. Ever since, the team has been cognizant of not overloading the rovers’ flash drive. Plus, solar conjunction is coming up at the end of November.

During this two-week time period when the Sun is between the Earth and Mars, communications between the two planets are blocked. That means the robot field geologists will be on their own. From November 29 through December 15, Sols 1745 to 1760 for Spirit, all science and engineering data collected must be stored onboard in the flash memory. So, the rover began this month allotting some of its power every day to relaying data to the Odyssey orbiter, instead of phoning home every fourth day as it had during Martian winter, and freeing up space in its flash memory.

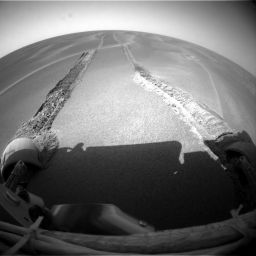

Dusty arrays

Dusty arraysSpirit took this image of its solar panels with its Pancam this month. The arrays are so coated in Martian dust they look like sandpaper. And, even though the rover "bumped" to better angle itself toward the Sun, the dust in the skies overhead fluctuated up and the power-challenged Spirit lost a little energy in October. It wasn't enough, however, to stop this rover.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

After weeks of remarkably clear skies over Gusev Crater, atmospheric opacity or tau, a measure of atmospheric dust, began to increase, from 0.134 to 0.209, then 0.294 as October played on. Rover operators continued throughout the month to keep close tabs on the dust levels, because of their impact on the rover's power. While the increase or upward trend was expected because it's that time of the Martian year, historically, the rovers have experienced higher dust levels. Overall, the skies are clearer than they might have been, but Spirit’s power levels dropped anyway.

Undaunted, the rover carried on, checking drift in the Mini-TES, surveying the sky and ground with the instrument, and homing in on a couple more potential high silica targets dubbed Jules Verne and Stapledon. It also took some lower tier images to further enrich the Bonstell Pan. Known as the "Bonestell lower tiers," they are sort of finishing touches to the lower edge of the full-color panorama. After that task was complete, on Sol 1697 (October 11, 2008), the rover parked the Pancam with its mast assembly pointed below the horizon to minimize dust contamination.

As the second week of October turned to the third week, Spirit snapped spot images of the sky for calibration purposes, surveyed the horizon, took some thumbnail images of the sky. It also managed to take more surveys of the ground and the sky at different elevations with the Mini-TES, the time to send data home every sol, and it even spent quality time recharging the battery.

After a long motionless winter, Spirit finally "bumped" a move on Sol 1709 (October 23, 2008). The rover only moved 8 centimeters (3.1 inches), but after months of not turning its wheels, it was another milestone met. "We got the downlink [last] Friday," said Squyres. "Frankly, I was going to be happy if all 5 good wheels turned. And it worked just great. Granted, the front right wheel, which is the one that doesn't turn, was never completely down the slope. It was more on the top edge of Home Plate. But as I was telling the team earlier, the last time we drove Spirit, Phoenix was in cruise. I mean, if you leave your car sitting in the driveway for 245 sols, you're going to be a little nervous when you turn the key."

The bump effectively repositioned the rover from an almost 30-degree angle to a 25-degree angle, according to Matijevic, putting it in a better position to take in the Sun’s energy. Even with the increase of dust in the skies and despite its extended bout with low power, Spirit continues to demonstrate it has the right robot stuff. Somehow, it is still taking in 32 percent of the sunlight beaming down and generating enough electricity to keep on going.

This last week, the priority for Spirit shifted to communication, specifically getting all the Pancam images stored in its flash memory downlinked to Earth. "We started to do this at the beginning of October and we'll be continuing with that through the next 4 weeks," said Matijevic. "The strategy here is to get ourselves ready for the conjunction that's coming and part of that is to empty parts of flash out for the purposes of allowing us to collect data for those 2 weeks or so when we're not in communication with the vehicle."

The total capacity of the rovers' flash drive is 1.5 gigabits, or 1500 megabits. "The last report says we have 599, effectively 600 megabits of empty flash onboard Spirit," Matijevic noted. "We were down into the 300s in the early part of October.” The team’s informal goal, for both rovers, is to try and get as much as 1000 megabits freed up.

Although the bulk of Spirit's memory is filled with Pancam pictures, there are "a few other science measurements" and engineering data still contained within that memory, said Matijevic. "We've been slowly getting rid of some of the engineering data that's in there. There were some left over motion images that we took when we were bumping down the side of Home Plate and a few other odds and ends that are collected routinely as part of our operation. Really, we're just trying now to make a concerted effort to get the most recent science data back.”

In coming sols, Spirit will move again, maybe two more bumps, to get it in as perfect a position as possible for solar conjunction. The engineers at JPL would like to have the rover at a 20-degree angle soon in order to take full advantage of the Sun's position in the sky during the solar conjunction. So, the plan is to have the rover bump again sometime soon. The decision is “power-related,” said Squyres. “We're going to keep our eye on the tau.”

Spirit’s long-range objective, meanwhile, remains the same. One way – or another – the rover will head south of Home Plate to von Braun, a prominent mesa with a bright cap rock on top, and a non circular hole in the ground, affectionately called Goddard, after the pioneering racketeers Werner von Braun and Robert Goddard, for whom NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland is named.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

During the final sols of September, Opportunity crossed the 12-kilometer (7.5-mile) milestone during a series of 125+-meter drives, setting a new distance record for Mars rovers. It had barely logged that achievement, when the MER team decided it would chart another 12-kilometer trek, this time to a crater 20 times the size of Victoria, which the tean has dubbed Endeavour.

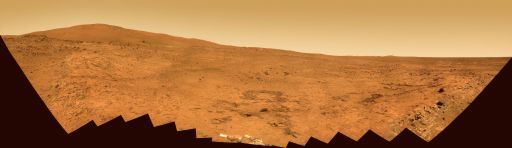

Opportunity route map to Sol 1691

Opportunity route map to Sol 1691By Sol 1691 (Oct. 25, 2008) Opportunity was more than 400 meters to the southwest of Victoria Crater. It left for good on Sol 1683 after 2 years of study. The rover is heading for an area where the north-south dunes of Meridiani Planum are spread thinly over exposed bedrock, a landscape that presents a veritable "highway" for its journey south. The inset to the upper left shows the terrain between Victoria and Endeavour. Grid lines are spaced 100 meters apart.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / Eduardo Tesheiner

As the calendar turned to October, Opportunity was bounding with energy. Having had its solar arrays dusted off by wind guys several times in the last couple of months, the rover began the month with power levels hovering around 652 watt-hours. Once its next major destination was determined, Opportunity traveled south around the rim of Victoria Crater, stopping for photo shoots of two last promontories or capes along the way. "We have really been covering a lot of ground," said Squyres.

The rover began the month of October (Sol 1667) by conducting routine atmospheric dust measurements and taking a systematic survey using all 13 panoramic camera (Pancam) filters. Then, Opportunity jumped into a busy first week of the month. Beside taking the routine atmospheric measurements, keeping an eye on the dust, and daily uplinking of data to the Mars Odyssey orbiter, Opportunity drove a distance of 143 meters -- more than twice the wingspan of two Boeing 747's parked side by side.

The rover took the planned images of the promontory inside Victoria Crater known as Cape Pillar and began the drive to another vantage point for taking images of a promontory known as Cape Victory. It also studied the atmosphere, searched for Martian clouds, and scanned its external dust-collection magnets.

Sol 1670 (October 4, 2008) was a typical full worksol for Opportunity. The rover searched for morning clouds by acquiring a six-frame, time-lapse movie with the navigation camera, and took thumbnail images of the morning sky for calibration purposes with the Pancam. Before starting the day's drive to photograph Cape Victory, it acquired a panel of images with the Pancam, then after the drive took another panel series of images with the navigation camera.

The following sol, the rover acquired a tier of images of the terrain, overlapping the frames to compensate for dust on the lens of the Pancam, then used all 13 color filters of the camera to take a systematic survey and images of particles on its external magnets. Once its science data packaged was beamed to Odyssey, Opportunity measured atmospheric argon with the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS).

Clouds over Victoria

Clouds over VictoriaOpportunity turned its rover eyes skyward to observe clouds drifting overhead in March, much like it has throughout the mission. The clouds it captured here passing over Victoria Crater look like cirrus clouds on Earth, featherlike formations composed mostly of ice crystals.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / Texas A&M / Navigation camera

After taking thumbnail images of the morning sky for calibration purposes with the Pancam and producing a six-frame movie in search of clouds with the navigation camera on Sol 1673 (October 7, 2008), Opportunity continued driving south and completed a "get fine attitude" procedure to determine its exact position relative to the Sun. After the drive and before sending data to Odyssey, it took two panels of forward-looking images and a rearward-looking mosaic of images with the navigation camera, and another panel of images with the Pancam.

It’s almost hard to believe that after two Earth years, Opportunity’s work at Victoria Crater finally came to an end. "The last promontory we were on we named Cape Agulhas," Squyres informed. "It means Cape of the Needles in Portuguese. On Earth, it's the southern most tip of Africa, kind of the last place where the Victoria touched land before heading off into the Atlantic Ocean, so it seemed like a good name.” Opportunity looked to Cape Victory from Cape Agulhas and took pictures with its Pancam. “Then,” said Squyres, “we just turned around and hit the gas.”

Meanwhile, down on Earth, the MER team had been studying orbital images of the area taken by the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) scanning the landscape to chart a “roadmap” for Opportunity. The most powerful camera ever to orbit the Red Planet, HiRISE, from the beginning, has been taking pictures that are aiding scientists and engineers alike working in all the other missions at Mars. The pictures are revealing detail never before seen, and in the picture you can actually spot the spacecraft on the planet, from Viking to the Mars Exploration Rovers to Phoenix.

Before leaving Victoria Crater, Opportunity did something on Mars it had never done before on Sol 1680 (October 14, 2008) -- "the Mini-TES mirror shake," as Squyres calls it. Back in June-July 2007, this rover took the brunt of the global dust storm and the optics on its miniature thermal emission spectrometer were saturated with the powdery, electrostatic dust that is everywhere on the Red Planet. By shaking the mirror on the Mini-TES – something MER team members learned they could do by accident back during testing and before launch – they’re thinking just maybe some of that dust will fall off. "It's not a violent vigorous shaking," Squyres noted. "It's a very light vibration. I'm not optimistic it will, but it may work. Mars has surprised us before. We'll try it a number of times."

“The intent is to do it again and perhaps do it repeatedly during the same sol's activities and hope for the best,” elaborated Ruff. “But there's sort of an empirical reality that we have observed with the Phoenix mission with regard to these fine particles on Mars and how sticky they can be. Mars is a very different place with regard to fine powdery materials, in large measure because of the electrostatics. The low atmospheric pressure and the near absence of water in that atmosphere really leads to the potential for electrostatic forces that can cause things to stick up there in ways that are unusual, at least for Earth. Everyone realizes that this vibration technique is a bit of a long shot. The reality is these electrostatic forces may preclude this particular approach. It may not work.” But the team is nowhere near giving up.

If shaking the mirror doesn't work, they've still got one more card to play or “Plan B,” as Ruff calls it. And it’s simple, passive. "Just leave the cover open and let Mars clear it off for us,” said Squyres. “Will that work?” he asked “I don't know,” he answered. “ We did pick up a fair amount of dust on the Pancam optics during the dust storm and with time those optics have become more and more clear. So Mars is cleaning off those lenses for us. Maybe it will clean off these mirrors for us too if we give it a chance.”

“It's certainly in our back pocket as an approach,” added Ruff. “In all this time on Mars, we've intentionally closed Mini-TES off to the elements, in fear of making it worse. Ironically,” he mused, “we just may be making it worse by keeping it closed.” At this point, it couldn’t hurt to try anything on Opportunity’s Mini-TES since the instrument is useless for science. “We really don’t have anything to lose. That's why we're trying these things.”

By mid-month, Opportunity was on the Meridiani Highway leaving Victoria in the dust, for good. The rover headed south/southeast toward an area of outcrop, not yet named. "We sort of talked about it in same sense as the area between Endurance and Victoria called the ‘etched terrain,’" said Matijevic. "This is very much like that. It's like it's picked up again as we move south from Victoria Crater."

Opportunity began encountering some classic Meridiani ripples. Some are small, "on the order of not more than 10 centimeters tall," said Matijevic. Others are larger, around 35 centimeters tall, reminiscent of Purgatory Dune, where Opportunity got stuck while it was driving carefree across the plains toward Victoria Crater back in April 2005. Purgatory Dune was such a memorable experience that MER team members are now referring to these larger ripples as “purgatoids.” Such is the fate sometimes of challenging things discovered.

The HiRISE camera images of this general region around Victoria Crater, though, are helping the MER engineers and scientists to see what lies ahead in a way no other mission ever has before. In those images, they noticed an area more or less toward the southeast direction from the rim of Victoria Crater where you can see ripples that are on the order of 35 or more centimeters. “This definitely represents the kind of place where we would not want to send the vehicle simply because of the embedding danger there," said Matijevic.

"We're already doing a lot of swerving to avoid Purgatoids," Squyres noted. As a result, Opportunity is heading more toward the southwest now and an area that doesn't look so purgatoidal. "We've been in this area that's known the annulus region," said Matijevic. "This is a region that was kind of featureless from previous orbital images, and encompasses the crater about 500 meters or more out depending on what direction we're looking at. We're probably about 2 drives away from the end of that, going toward the southwest."

Purgatoids or not, Opportunity isn’t wasting time and it isn’t shying for the drives. "We're trying to drive pretty aggressively because we have such a long way to go,” explained Squyres. “We're using a drive strategy that potentially allows us to get a little bit stuck in a purgatoid, because we know how to get out of those things now. We don’t want to drive so aggressively the rover gets stuck often and we blow sols over and over again, spending time getting out of dune. But we don't want to drive so timidly that we don't make enough progress on each drive.”

Like everything challenging and highly rewarding, it's about finding the right balance of aggressiveness and caution. "There's a middle ground that I think we're getting pretty good at finding now,” Squyres said,

By early next week, the MER team expects Opportunity will be seeing the first sort of outcrop areas in the new ‘etched terrain’ area. "We'll also be in an area where we'll have to pick our way through a little more carefully," said Matijevic. "But this will mark almost a kilometer's worth of driving just since the team decided to go to Endurance,” he pointed out.

Opportunity's agenda for the next month is more of the same all the way through solar conjunction – “drive, drive, drive," said Squyres. "We covered 216 meters in a single sol last weekend. We had a number of 100+-meter drives planned in the sols since. "We have a long way to go to get to Endeavour,” he reiterated. “And we are giving it our best shot."

"Opportunity will drive 3 days this week and will probably drive 3 days next week," added Matijevic. "We could be driving everyday if we weren't in is such that we lose an uplink opportunity and occasionally have some long latencies in downlinks. We don't exactly get everyday the way we wouldlike to get them. But as long as we are clicking off 100-150 meters, we can do pretty well in covering ground.”

Yes, the elusive cobble study is still on the agenda. The MER scientists are just waiting for the right cobble, one they can put the IDD down on and leave through solar conjunction. "We haven't found one yet that really was worth a stop," Squyres said. "We are particularly interested in trying to find a good IDD target – either bedrock or a cobble – for superior conjunction, when we spend basically 2 weeks parked motionless. That's a great time to do a long Mössbauer spectrometer integration," he said.

Getting a measurement of how much iron is in a target takes quality time with this spectrometer these days. "Every time we go through another half-life the duration doubles – the half-life of the Mössbauer's radioactive source is 271 days -- so it takes a long time," Squyres said. "How long exactly depends on the signal-to-noise ratio and the iron content of the target, so there is no one-size-fits-all answer to that." In any case, having 2 weeks to do a Mössbauer integration would be ideal. "We would spread the integration during portions of the day when you've got the power to do it over a total of 2 weeks. So, at the start of conjunction, we would park the Mössbauer on a rock, then just turn the instrument on for a significant period of time every single day for the entire conjunction," he explained.

"Anytime we see a good cobble, we're going to jam on the brakes and go after it," Squyres assured rock hounds, "but right now we're just trying to cover as much distance as possible."

Like Spirit, Opportunity has a bunch of stuff stored in its flash memory and is communicating daily in an effort to send the data home and free up room for all the observations, measurements, and pictures collected during the solar conjunction. "We haven't gotten all of the images and data down from the Pancam work at Cape Pillar and Cape Victory," said Squyres. "There was some very nice super-res imaging we did on Cape Victory, which we do not have on the ground yet, because we've been driving so much."

The drives generate a lot of data and that mobility-related data comes down at a higher priority than the science pictures of the cliff, for obvious reasons; therefore, a lot of science data remains in flash on the vehicle. "We've been driving so much that we've just got a lot of drive-related data that has been streaming down," Squyres explained.

Perhaps the best news of all for Opportunity this month is that it has not had any repeat of the current spike it experienced on the left front actuator a couple months ago. "Everything's back pretty much to normal," said Matijevic. "We've been checking the draw on the drive actuators after every drive and they've been generally all within nominal levels. So we're just going to keep moving along."

Really moving along. As November dawns, Opportunityand crew will proceed with more caution through the looming sea of puragtoids, but, said Squyres, “we're going to go as fast as we can.”

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth