Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Hibernates Still, Opportunity Pulls into Cambridge Bay

Written by

A.J.S. Rayl

Contributing Editor, The Planetary Society

August 31, 2010

With the Sun beginning to warm the landscape in the southern hemisphere of the Red Planet and winds whipping up here and there forming dust devils that kick the powdery, rust-colored topsoil into the atmosphere, the Mars Exploration Rovers have been experiencing sure signs of a Martian spring this month.

Although Spirit continued to sleep in, presumably still charging up her solar-powered batteries with ‘fuel’ from the Sun, Opportunity seemed to have the wind beneath her ‘wings’ as she put another half-mile behind her this month on the 15-mile journey from Victoria Crater to Endeavour Crater, despite making two stops to rest and to conduct some research.

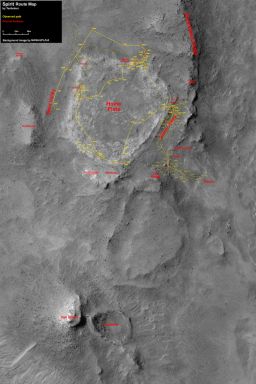

At Gusev Crater, Spirit remained silent throughout the month, parked in Troy on the west side of Home Plate. The rover has been there for some 16 months now, snarled in a patch of sand, and since March in hibernation. “We’ve heard nothing from Spirit yet,” said Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, during a recent interview.

The last time the MER team heard from Spirit was on Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010), when the rover displayed a very low level of power, and all indicators were that it would soon trip a low power fault. If the robot followed programmed protocol, then it shut down all systems, and went into a kind of hibernation mode into order to recharge its main power batteries. Although no one expected to hear from the robot for months, the rover engineers within days began keeping a radio ear tuned just in case the rover beeped.

“We’re still listening for Spirit, and very little has changed from last month to this month,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the twin robot field geologists were “born” and are being managed. The one change, he noted, is that engineers, beyond just listening everyday have increased the amount of time they spend each day conducting sweep-and-beeps. In this space communication procedure, engineers actively reach out to Spirit, sending a signal and asking the rover to respond. Even so, they are calling out during very narrow windows of time with no idea of when the rover might be listening.

If the hardest part is the waiting, then the most unnerving part of the waiting is that no one really knows how the rover is doing. "We don’t have any measurements from Spirit so we don’t know exactly what’s going on with her,” reminded Mars Rover Driver Team Lead Scott Maxwell, also of JPL. “The only thing we know for sure so far is that we haven’t heard from her yet.”

Listening for Spirit

Listening for SpiritFront view of the 70-meter dish, also known as DSS-14, at the Deep Space Communications Complex at Goldstone, California. Located in the Mojave Desert, Goldstone is part of NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN), which provides radio communications for all of NASA's interplanetary spacecraft. It is also utilized for radio astronomy.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

But that, confoundingly, doesn’t necessarily mean she hasn’t been trying to signal her home team. If the rover’s clock has stopped functioning, which engineers think is a possibility, it means Spirit has no idea what time it is and could be waking up and going back to sleep at the most illogical of times.

Considering the legendary MER resilience and Spirit’s past performances in the worst of times, there’s no reason to believe this rover has done anything other than what it was programmed to do. So, despite the sounds of staticky silence, Spirit’s team continued to gather electronically for meetings in August, “patiently waiting,” Arvidson said, still cautiously confident the robot will be phoning home.

Now, as August gives way to September, the three-month wake-up spread posited months ago begins. With various planetary models as the basis, many rover engineers have been marking September, October, or November as the month when Spirit will emerge from hibernation and send out a series of beeps. “Nothing has changed that outlook,” Callas confirmed. “The odds,” Maxwell held, “are really good a couple of months from now.” That would be late October. For the time being, the MER team will continue to listen and reach out to the rover every day.

Over on the other side of Mars, Opportunity began and ended the month at Meridiani Planum with stops “to smell the roses,” said Callas. After wrapping up work on a ripple called Juneau at the top of August, the rover put the pedal to the metal, logging some 770.85 meters (2,529 feet or 0.478 mile) before stopping the weekend of August 21-22 to take a break and inspect an outcrop called Cambridge Bay.

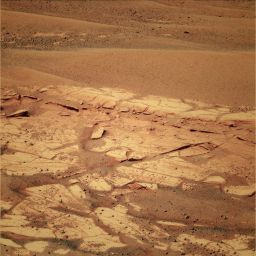

Cambridge Bay

Cambridge BayOpportunity made her second rest stop weekend before last, at Cambridge Bay. The rover took this image with her Pancam and this version was colorized by Stuart Atkinson. If you click on the picture, you will be able to see all the layers and plates in this transitional area where the soil-rich and sand dune dotted landscape gives way to more solid bedrock.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / processed by Stuart Atkinson

Always the lucky rover, Opportunity was “about due” to stop to make “another periodic measurement on outcrop” in its campaign to see if there’s any “lateral variations” in composition or mineralogy of the surface between Victoria Crater and Endeavour Crater, Arvidson noted, and Cambridge Bay is “a rocky outcrop that looked really interesting.” Interesting because it appears to be a kind of boundary area between soil rich and dune dotted terrain to flatter, bedrock heavy flatlands and because that indicates the rover is crossing a kind of threshold on the way to her next big attraction.

At Cambridge Bay, Opportunity has been homing in on “a purple colored stratum sandwiched between buff colored strata,” Arvidson said. “It is intriguing because it may be an altered horizon or a different facies within the sedimentary rocks,” he elaborated yesterday. “We will be seeing more outcrop and fewer ripples as we head east and southeast to Endeavour, but this is not a discrete boundary. Rather, it is transitional,” he said.

The rover is scheduled to wrap up research at Cambridge Bay and get back on the road to Endeavour today with another 70+-meter drive.

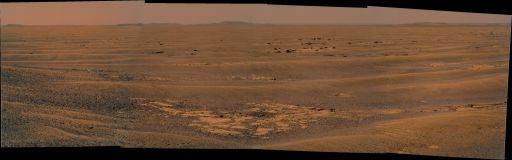

It’s been nearly two years since Opportunity set out on the cross-planum trek from Victoria to Endeavour and it’s got one to two more Earth years to go. The robot field geologist is roving well and optimism among MER team members is as high as it’s ever been that Endeavour is within reach. “We’re six miles away [9.65 kilometers] and we can see the thing, and it’s made everybody that much more excited and eager to make it there,” said Maxwell.

Eager may be something of an understatement, for both engineers and scientists. This month the MER science team threw down a gauntlet to the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) crew and their bigger, faster rover Curiosity. “We’re going to try and beat MSL to find phyllosilicates,” Arvidson announced. The mission’s Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, politely presaged the race in previous editions of the MER Update, but it’s official now if it wasn’t before: the race is on.

Endeavour on the horizon

Endeavour on the horizonOpportunity took this picture with its panoramic camera (Pancam) late this month, on its Sol 2337(Aug. 20, 2010. It was processed and colorized by Damien Bouic, aka Ant103, who posted it last week at UnmannedSpaceflight.com.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / processed by Damien Bouic

Phyllosilicates are minerals that form in neutral to alkaline chemical conditions as opposed to sulfates, for example, which favor acidic conditions. Finding these minerals on Mars is significant because biologists view more neutral and alkaline water conditions as more conducive to the origin of life. So, where there are phyllosilicates -- such as mica, chlorite, serpentine, talc, or clay -- there may have once been a haven for life to emerge.

As fate would have it, clay minerals, specifically smectite, a type of phyllosilicate brimming with iron and magnesium, was indirectly detected along the rim of Endeavour Crater. The evidence appeared in orbital data collected by the Compact Imaging Spectrometer (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and reported in a paper published earlier this year, even as Opportunity has been blazing a trail to the humungous hole in the ground.

Although Curiosity isn’t even at the pad yet much less off it, the race could be close. The MSL rover, whose mission is to determine whether Mars ever was or is still today an environment able to support microbial life, is slated to launch in November 2011. If all goes as planned, six to seven months later it will rocket down to the surface at a still-to-be-determined site. That likely will be about the time Opportunity is closing in on Cape York, its “landing” site at Endeavour Crater, where phyllosilicates await.

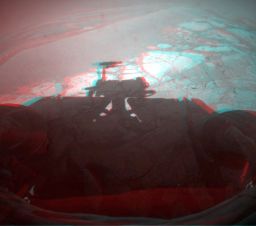

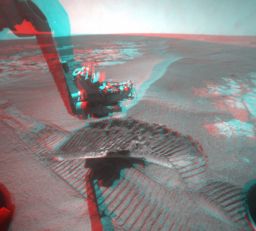

Opportunity self portrait in 3-D

Opportunity self portrait in 3-DOpportunity took another self-portrait this month. Rover poet and image processor Stuart Atkinson has turned it into a 3-D experience.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / processed by S. Atkinson

At this point, the near future looks pretty bright for the rovers. “Things are continuing to improve energy-wise as we go through spring towards summer, and we expect it should aid both rovers,” said Callas. “The solar insulation should be improving at the Spirit site, but this is also the time of year in which we get changes in atmospheric opacity [dust in the atmosphere] and the expectation is that the opacity will deteriorate over Gusev as it has done after the previous three Martian winters,” he pointed out. “It’s been very regular, almost like clockwork in the past.”

The notorious Martian dust is beginning to imbue the sky with a slightly hazier shade of rusty red, but the immediate forecast is benign. The latest weather report from the Malin Space Science Systems’ team operating the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) showed relatively clear skies over both rovers.

With the bad comes the good on Mars, at least sometimes, and as the winds stir up the dust in coming sols and weeks, they could do Spirit a favor and whisk away some of the accumulated dust from her solar panels like it did for Opportunity last month. That’s certainly near the top of the team’s wish list for Spirit, and it’s not really all that much of a stretch. It was in this very area that Spirit, a little more than one Earth year ago, experienced, arguably, the most dramatic array cleaning she’d ever received, save maybe one event way back on Husband Hill. So all fingers are crossed for a windy repeat.

Meanwhile, Opportunity, now sporting plenty of power, more than half the power she had on landing back in January 2004 actually, will be roving ever onward in coming sols through the area of transitional terrain. “We’re six and a half years into their 90-day mission and still doing brand new things,” summed up Maxwell.

Down on Earth, the team is still trying to keep up as MER scientists finish up work on papers for the next special issue of the Journal of Geophysical Research, published by the American Geophysical Union (AGU). There is a wealth of data coming, Arvidson informed, with some 20 papers going under review for publication. [Check in next month for a hint of things to come, including what they’re doing with all the argon measurements that the rovers have collected during the last seven years.]

In hibernation

In hibernationSpirit appears on the shoulder of Home Plate in this FX image created by Glen Nagle, aka Astro0 at UnmannedSpaceflight.com, where the rover became bogged down in the sands of Ulysses at Troy. The rover took this panorama on her Sol 743, as she descended from Husband Hill and roved toward Home Plate. Home Plate is the plateau occupying the center of the image. Click to enlarge and you will see Spirit in the valley to its right. Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Glen Nagle

Spirit from Gusev Crater

Just a few days after Spirit ostensibly experienced a low-power fault and went into a deep sleep to recharge last March, the team began listening with the Deep Space Network and the Mars Odyssey orbiter for a series of beeps that would be the rover’s autonomous recovery communication from the low-power fault. Although they didn’t expect to hear from the rover for months, neither Spirit nor Opportunity had ever gone into hibernation before, this was new engineering territory, and they wanted to be there just in case.

So no news from Gusev Crater this month is actually not bad news. “Spirit might not have even started waking up yet,” as Scott Maxwell pointed out.

Spirit route map

Spirit route mapThis image taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO has been labeled by Eduardo Tesheiner, an active participant on UnmannedSpaceflight.com, to show Spirit's route from its arrival in the Home Plate area on Sol 743 through Sol 1871 (April 8, 2009), when the rover began suffering a series of bouts with 'amnesia.' By May 2009, the rover was mobility impaired, stuck in a sandy pit on the edge of a shallow crater. It is there now, hunkered down and waiting for the chill of winter to pass. Credit: NASA / University of Arizona / Eduardo Tesheiner

Since March, however, newer models over-turned old models to indicate that there is a chance Spirit’s power dwindled to such a low level that she also tripped a mission clock fault and lost track of time, as reported here in a previous edition of the MER Update. If this has happened, then the rover will remain asleep until there is enough sunlight on her solar arrays to fully charge the batteries and wake her up, a state the team calls ‘solar groovy.’

In that state of grooviness, Spirit would simply listen for 20 minutes each sol for a communiqué from Earth, as opposed to reaching out with her own series of autonomous beeps like she would if she has not tripped the mission clock fault. And, the rover would be keeping time to her own clock, having started her clock anew on waking up and not being able to synch to the mission clock at JPL. That means the rover could be waking at any time day or night to listen … and there’s just no way of knowing when exactly.

Based on models and the last three Martian years, “in the best of all possible scenarios we might have heard from Spirit right around the end of July or beginning of August,” said Maxwell. So last month, beginning on the rover’s Sol 2333 (July 26, 2010), the team, beyond just listening, initiated an additional sweep-and-beep procedure to reach out to the rover in case she has indeed tripped the mission clock fault.

For the sweep-and-beeps, the DSN mission controllers send a set of X-band beep commands. “We’re sending her a command that says: ‘If you’re awake, send us back a beep tone.’ That’s it. That’s all we’re trying to do,” said Maxwell. “We’re not trying to wake her up, or get control of her or anything else. We’re just asking: ‘If you’re there, let us know.”

Since they just don’t know if or when Spirit has restarted her clock or when she might be getting up, “it’s all a guessing game” for the engineers, Maxwell said. “She could be waking up in the middle of the night, or noon, we just don’t know,” he added. “We’re kind of rolling the dice every time we’re trying to communicate with her, and we only have a few shots at it each day.

Moreover, because the engineers have to get the entire commanded sweep-and-beep communiqué to the rover during one of her 20-minute listening windows, timing is everything with this approach. “We can only send this command over the low gain antenna and it takes us somewhere around 11 minutes to do the whole sweep-and-beep activity, that’s sweeping her receiver into range and then sending the command on top of that,” Maxwell explained.

Spirt's winter position at Troy

Spirt's winter position at TroyYou can see Spirit in the upper right quadrant of this image about a year and a half ago by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO. The rover is at about 2 o'clock, appearing almost as if it's in Mars' spotlight. If you look closely, you'll see its form and head, and even the trail it plowed by dragging its broken right front wheel.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by Stuart Atkinson

On a typical sol, for example, Spirit might be awake for a 20-minute window at some random time during the sol, and the engineers must not only hit that window but also get their 11-minute sweep-and-beep completely into the window in order to connect with the rover. “Spirit has to be awake and listening -- and she has to listen to the whole command before she can respond,” Maxell confirmed. “That means the odds of us connecting right now are fairly poor. But, if we just happen to hit that 11-minute timeframe that’s completely within that 20-minute window of when she’s awake, then we win. And why not try?”

If Spirit does hear one of these sweep-and-beep commands, she is programmed to respond back immediately with an X-band beep signal that informs her team she is awake.

“Our odds get better as time goes along, not only because we’re changing when we’re trying to hear from her based on different theories as to when she might be awake, but also because, according to our models, she’ll be awake for longer and longer each day as the angle of the Sun on her solar panels gets better and better,” said Maxwell. Because of both those factors, the window gets wider and wider over time and we have better and better odds of getting in touch with her. So every day we have a little better of a chance to hear from her, and we do expect we’ll be hearing from her,” he added.

“Think of her maybe as your kid who’s gone off to college and she’s driving to another state and you know if everything goes perfectly she might possibly be there by 7 o’clock in the evening, but probably won’t get there until midnight or so,” Maxwell continued. “That’s the kind of feeling we have with Spirit. It’s remotely possible that if she got a cleaning event and everything went absolutely perfectly, then it’s possible she could be waking up from and we’ll be hearing from her about now.”

According to some models, however, the team might not hear from Spirit until April 2011 or so. “This could be the beginning of a 6,7,8-month long campaign,” Maxwell admitted. But the engineers’ best bets are still with “by November,” he said.

Simulation of Spirit's predicament

Simulation of Spirit's predicamentThis artistic image -- in which Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover -- illustrates Spirit's predicament at the location in Gusev Crater known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the casual reader a glimpse into the present scene on Mars -- and this rover scribe thinks it's a pretty cool illustration.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

Although August was pretty much a repeat of July for Spirit, the team did manage to increase its uplink time for the rover, from 60 minutes to 90 minutes, thereby increasing the number of sweep-and-beep commands it sends each day.

Spirit, as those following the mission know well, shares an uplink frequency with MRO, because way back when no one ever thought the rovers would last this long. “We always have to negotiate with MRO as to when we can do our commanding,” Callas pointed out. “With the additional 30 minutes, we have a little more opportunity to do sweep-and-beeps,” he added. [It is only in commanding or uplinking that they have to negotiate time with MRO.] “That’s been the only change since last month,” he added. “We continue to listen and we can do that anytime, because we have a way to work around MRO for listening.”

The time may come sooner rather than later when the MER team will try to negotiate more time from MRO to have larger window, Callas said. “But right now, this 90 minutes will pretty much be routine.”

Although the rover handlers have every reason to believe that Spirit’s power levels are improving with the advancing springtime in the southern hemisphere of Mars, they know too that the winds of the season will soon cause the skies over the rovers to get hazier with dust. “Spirit has never been the lucky rover and she could face the worst-case scenario,” Maxwell noted. “We do see an increase in tau somewhere around this time of year at Gusev, so there’s this brief period of time where things will get a little better, then worse, and then get better after that.”

Home Plate

Home PlateSpirit acquired this full resolution mosaic of Home Plate on Sol 1886 (April 23, 2009), before a drive, as the over made its way around the western edge of the circular volcanic formation. The field of view spans about 90°and this mosaic, in approximate true color, was created from Pancam's 753-nanometer, 535-nm, and 432-nm filters.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

In the meantime, Spirit remains hunkered down just to the west of Home Plate, her odometer unchanged, reading 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles); the team is “patiently waiting to see what happens,” said Arvidson. “We’re really just going to keep trying to talk to her and to get her to beep to use to let us know she’s okay, and we’ll be trying that through the next few months,” added Maxwell. “We have a good solid expectation we’ll hear from her by November.”

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

When August dawned at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was on a break from driving and in the midst of a close-up study of bedrock, using her Pancam, microscopic imager (MI), and alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) in an area dubbed Valparaiso The data analyzed at this site will be added to all the other samples of rock and soil that the rover has been collecting every kilometer (0.62-mile) or so since leaving Victoria Crater nearly two Earth years ago. Ultimately, all the research will be used to determine how and where the surface between Victoria Crater and Endeavour Crater changes.

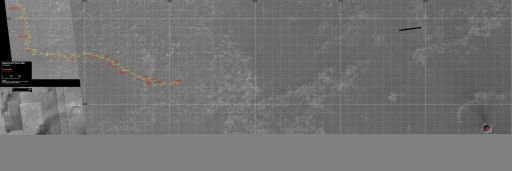

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis route map, created with an orbital image taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and labeled by Eduardo Tesheiner, a senior member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com. It shows the rover's charted route from the San Antonio twin craters to its location at the end of this month.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

After wrapping research on Juneau and taking some additional pictures of her surroundings, Opportunity packed up and headed out. She roved out on Sol 2320 (August 3, 2010), logging an impressive 71-meter (233-foot) drive to the southeast on her continued journey to Endeavour, and then finished out the first week of the month with two more drives on Sols 2322, 2324, (August 5, 7, 2010).

Opportunity began the second week of August on Sol 2325 (August 8, 2010) by making another Autonomous Exploration for Gathering Increased Science (AEGIS) observation in search of possible science targets. This time, however, the rover didn’t identify any “scientifically interesting” rocks or soil patches in the collected images.

“We had a number of runs over the past few weeks that have gone well,” Tara Estlin a rover driver, senior member of the Lab’s Artificial Intelligence Group, and leader of development for this new software, told the MER Update earlier this month. “We've done things like look for rocks based on their reflectance, for example, look for light rocks on one sol and dark rocks on another.”

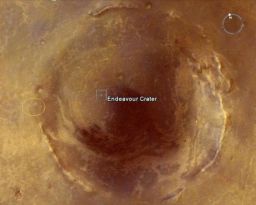

Opportunity's port at Endeavour

Opportunity's port at EndeavourThis image taken by the University of Arizona's High Resolution Imaginging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter gives you an idea of where the MER team plans to have Opportunity pull up to Endeavour Crater. At least for now, this is general area where the rover is slated to arrive and begin its tour.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / UA / labeled by Stuart Atkinson

As it turned out, on the runs where Opportunity looked for light rocks, the rover in each case found “good pieces” of outcrop, Estlin noted. “The dark rock run found a dark area of soil, which I thought was a great result since areas of darker soil, such as gravel patches, have been seen before in Meridiani and are something the scientists have wanted to target,” she said.

The AEGIS software team also experimented with having Opportunity do two runs where she looked in the same direction but at different times of day to see if that changed the target the rover selected. “It did,” Estlin said, “but the targets were only a few centimeters apart.”

As Arvidson mentioned in last month’s MER Update, Estlin and the other engineers on the AEGIS software team continue tweaking parameter settings. “We are trying to find the best ways to run it in order to acquire different types of rock targets,” explained Estlin. “For instance, we already have an ‘outcrop profile’ for AEGIS that is very good at finding pieces of outcrop in a sea of dunes. And we are working on setting up a ‘cobble profile’ that will be good at finding loose, darker rocks and will support Opportunity's cobble campaign.”

These AEGIS targets have typically not been named, but, in part, that is because of how they are acquired, Estlin noted. “If a target is manually picked out of an image on the ground and we want to take additional images of it, then the science team typically names the target, so it can be referenced in the sequence and sol notes,” she explained. “However for AEGIS, the software is autonomously both picking out the target and acquiring the additional images and is in a sense skipping the typical naming step. However, she added, “I'm sure if we find something really interesting, then the target would eventually be named.”

With its AEGIS assignment complete, Opportunity shifted again into high gear the second week of August, checking off another series of 70+-meter drives on Sols 2326, 2327 and 2328 (August 9, 10 and 11, 2010).

Throughout the month, Opportunity continued to drive backwards exclusively, as she has been for months now, and she seems to be cruising right along. “Backwards is the way to go,” said Arvidson. “We’re putting mileage on the odometer.”

Checking out Juneau

Checking out JuneauIn this 3-D image assembled by Stuart Atkinson, Opportunity is checking out the under-surface soil on a target dubbed Juneau.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Indeed. All told, the rover logged more than 350 meters (1,148 feet) and saw the 22-kilometer (13.67 miles) mark on her odometer come and go during the first six drives of August.

Rover engineers instructed Opportunity to begin driving backwards last year as a way of mitigating or alleviating the strain on the actuator or motor to her right front wheel that was consistently drawing more than normal current compared to the other wheels. The same thing happened years ago just before Spirit lost the use of her right front wheel, so the engineers took no chances. Along with the backward driving, they prescribed occasional rests for Opportunity.

The techniques, however simple they may seem, appear to have worked as well as anyone could expect, essentially resolving the rover’s “hot wheel” issue. “The wheels are very well-behaved,” reported Callas. “We’re quite pleased with the current levels of all the wheels.”

Past that, Opportunity is apparently feeling pretty good. Almost every commanded drive this month was 70-meters (230-feet), and was generally followed with short drive segments of autonomous navigation (AutoNav) in an attempt to extend the drive distance each sol.

The MER rover drivers had Opportunity implement AutoNav while driving backward for the first time last month, as reported in the MER Updates for June and July 2010. It’s a simple workaround: having the rover turn one direction, and then to the next in order to image the drive path with her navigation cameras, the view of which is blocked by the Pancam assembly mast and low gain antenna when the cameras are focused directly ahead, in the drive direction.

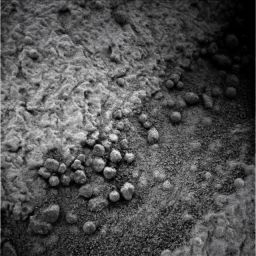

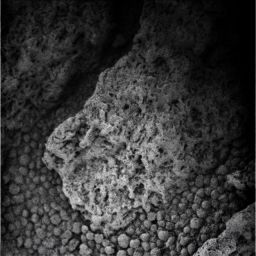

Cambridge Bay close up

Cambridge Bay close upOpportunity took the series or stack of images that went into this image with her Microscopic Imager. It pretty clearly shows the detail on those rocks and in the gravel around them. "These have been enhanced and tweaked mercilessly, simply and unashamedly to make them look more dramatic," says Stuart Atkinson, who processed themCredit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / processed by Stuart Atkinson

“The [AutoNav driving backwards] is working okay for us,” reported Maxwell. “We’re not getting as much distance we would like. But the good news is that what’s been scaring Opportunity so far are mainly ripples that she sees at the edge of her peripheral vision. This little technique we’re having Opportunity use [in reverse AutoNav] allows her to see a channel that is just wide enough for her to drive down,” he continued. “Like everything else on these rovers, she interprets any obstacle seen at her peripheral vision as conservatively as she possibly can. And, since it might possibly be a hazard, she grows it to her own radius [with her hazard software]. When she does that, the obstacle encroaches onto that little path we’re allowing her to drive through and she refuses to drive past it,” he said.

In reality, if an obstacle is off to the side, visible only in Opportunity’s peripheral vision, it is usually safe, and if the rover’s field of view were a little wider with those cameras, she’d know it was safe. “But since she can’t prove it, she does the safe thing, and stops driving,” said Maxwell.

Despite her conservatively cautious ways though, Opportunity never stopped for long this month. “Right now, it’s about putting as much mileage as we can on the vehicle,” said Arvidson. In fact, the rover seemed to literally race through the second and into the third week of the month. On Sols 2329, 2330, 2333, 2334 and 2335 (August 12, 13, 16, 17 and 18, 2010), she chalked up more 70-meter drives followed by more short drive segments of AutoNav on those five sols successfully extending the drive distance each sol, if only by a few meters.

Another close up of Cambridge Bay

Another close up of Cambridge BayOpportunity took this close-up picture of Cambridge Bay this month, and Stuart Atkinson, MER poet and member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, processed it, enhancing it to bring out the detail. For more of Atkinson's words and pictures, go to:

http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.comCredit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / processed by S.Atkinson

“We have had at least one case where Opportunity was able to drive the entire distance we commanded her and another 17 meters on top of that,” Maxwell said. “On other sols, she’s added a few meters here and a few there with AutoNav, but in the end it all adds up.”

Actually, with those five drives, Opportunity added more than 330 more meters (1,083 feet) to her odometer, bringing her monthly total up to 770.85 meters or 0.478 mile before she made her next pit stop.

In the mix of driving and “housekeeping” duties this month, Opportunity conducted a diagnostic test on her miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) instrument on Sol 2332 (August 15, 2010). The instrument exhibited the same anomalous behavior as back on Sol 2257 (May 30, 2010), when it caused the rover’s Pancam mast assembly to ‘freeze’ and not move when commanded.

That event last May caused a moment or two of real concern among engineers who wondered if the rover had lost a motor in her neck that would forever handicap her. But they quickly traced the problem to the Mini-TES.

With the latest repeat of the anomalous behavior, the rover engineers and the Mini-TES team at Arizona State University (ASU) are back to the drawing board of investigation.

During the weekend of August 21-22, Opportunity paused her trek to Endeavour to examine an exposed rock outcrop of special interest to the scientists, dubbed Cambridge Bay. “The science team came across this very interesting spot where two different geologic units meet, a kind of boundary or contact point,” said Callas, “so we stopped for a few days to do some work with the instrument deployment device (IDD).”

On Sol 2336 (August 19, 2010), Opportunity performed a 7-meter (23-foot) backward turn with a forward bump to approach the outcrop. The next sol, the rover performed a short turn to place surface targets within reach of the IDD or robotic arm, zeroing in on “a purple colored stratum sandwiched between buff colored strata,” as Arvidson described it. The robot field geologist first used her MI to take close-up shots of a surface target called Clarin Beach. After that, she placedher APXS on the same target for a long integration.

The signpost up ahead

The signpost up aheadOpportunity has been on the road headed for Endeavour Crater since leaving Victoria Crater for good in September 2008. The rover has completed about one-half of the trip, with some 10 kilometers (about 6 miles) to go. Onward Opportunity. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / add-on by Stuart Atkinson

“If it was all up to me, I would prefer we would just charge across that outcrop and get to Endeavour,” offered Maxwell. “But I certainly do understand though why they want to do this systematic study of this expansive outcrop and not leave it all in the dust. Ray Arvidson was out here [at JPL] recently and he gave us a little preview of a paper he’s writing. One of the things he showed was a thermal inertia map of this entire region. Although there’s not exactly a clean dividing line between one and the other, you can really see right about where we are we are transitioning through a region with a lot of soil into a region with a lot less soil and presumably a lot more outcrop. That matches with what we see in HiRISE images as well. ”

So Opportunity continued her inspection of the Cambridge Bay outcrop into this week, collecting another set of MI mosaics of new targets on Sol 2341 (August 25, 2010), as well as APXS analyses of targets called Duero Beach and Laya Beach. The rover also invested quality time over several sols acquiring Mössbauer spectrometer data on a target christened Cervera Shoals in an effort to determine its iron content.

In the midst of this scientific research, Opportunity took some time on Sol 2339 (August 23, 2010) to participate in a relay test pass with the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, part of a regular checkout of the European orbiter’s relay. “The MEX demo pass executed as planned and both spacecraft report correct UHF radio operation,” said Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team at JPL. But they won’t know exactly how well the test went for a while.

“Data is currently onboard MEX where, due to other, higher priority MEX data, it will sit until 9/12/10 before being downlinked,” Nelson explained. “Once that happens, the data will be transferred through the DSN to JPL where it will be processed.” The MER team won’t actually see the data until then, and MEX has no ability to process or evaluate the data, he noted. “All they can do is pass it along.”

Opportunity is working and roving so well these sols, boasting power levels upwards of 550 watt-hours, that it’s easy to forget that she has her own share of physical challenges. Beyond her “hot” right front wheel, this rover has a broken shoulder.

American engineering

American engineeringThe Mars Exploration Rover (MER) design is a classic and current example of American ingenuity and engineering. When all else goes wrong on the home planet, Earthlings can look to the Red Planet in the night sky and take solace -- we still have two rovers exploring Mars, more than six and a half years after the twin robots bounced down to the Martian surface for a 90-day tour.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Since losing Joint 1 on her instrument deployment evice (IDD) or robotic arm back in April 2008, she no longer stows her arm when driving. Instead, the rover drives backward holding her arm out in a partially bent configuration, the so-called ‘fisherman’ position. Remarkably, the handicap hasn’t seemed to slow the rover down much, nor has it impacted her use of the sensitive scientific instruments on her arm.

“That’s been a really amazing thing to me,” said Maxwell. “The arm was not really designed to be left out during driving and we didn’t really think when we lost Joint 1 on that arm that we would be able to drive in such a configuration. Fortunately, it turns out, like a lot of things on this rover, the arm was built to better-than-spec and that’s one of the things that’s enabled us to do a lot better than we thought we were going to be able to do. Kudos to the team who built that thing for us.”

“For a vehicle that’s way beyond warranty, Opportunity is exceeding everyone’s wildest expectation, traveling well, and behaving well,” Arvidson added. “As we get closer and closer to Endeavour, we continue to shoot Pancam color and super-res picures of the rim, those parts we can see.”

It will still be a good long while before Opportunity will be able to take pictures of Cape York, the site where she is to “make landfall” at Endeavour. “The rim is connected and the northern part that is closest, Cape York, and the surrounding hydrated sedimentary rocks at Botany Bay, where we are heading, are on a lower part of the rim, so we just cannot see them yet,” Arvidson reminded.

For now however, the general goal is very much within sight and all eyes continue to be on the prize that awaits at Endeavour. “We have a taste now of what it’s going to be like,” said Maxwell. “The right front wheel is doing great, and we’ve been able to do these extended-distance drives without causing the rover to get anymore freaked out. I see more of that ahead in our near term future,” he added. “And, with the terrain changing, we’re seeing fewer ripples and more plain old flat outcrop. That means we should get more distance every sol … maybe as much as one hundred meters or so per sol, bombing along the terrain toward Endeavour, stopping once in a while to smell the roses.”

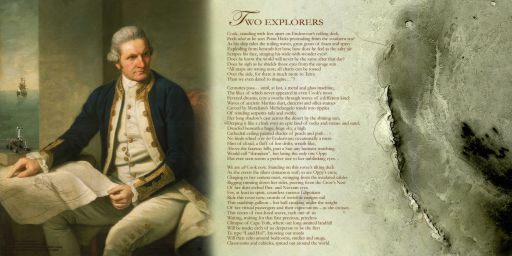

Two Explorers

Two Explorers: A Downloadable MER Poemster

MER poet Stuart Atkinson and artist Asro0/Glen Nagle, both of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, joined forces to present another in what should become a series of MER "poemsters.'

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Maas Digital / Cook image by Nathaniel Dance, NMM London /poetry by Stuart Atkinson / artistic composition by Glen Nagle

Support our core enterprises

Your gift today will go far to help us close out the year strong and keep up our momentum in 2026.

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth