Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 22, 2014

Women Working on Mars: Curiosity Women's Day

Just after completing the primary mission of 669 sols on Mars, Curiosity's managers planned a special day -- June 26, 2014 -- in which mostly women were assigned to the nearly 100 different operational roles. In all, 76 of 102 mission roles were staffed by women. All of the roles were filled by people who regularly work them -- the only difference, on this day, was that schedules had been aligned so that as many women as possible staffed those roles.

The special day highlighted all the different kinds of work it takes to keep this complex mission going. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory put together a terrific website explaining all the different jobs and how the team members work together to operate the rover. Are you interested in a space career, but the only space job you know of is "astronaut?" Explore this website!

To begin, it helps to understand the rover's tactical planning schedule. There are hundreds of people who work full- or part-time on Curiosity, but many don't fulfill an actual operational role every day. If they did, they'd have no time to do scientific research or work on improving software or do any of the other myriad things that make these missions and their professional lives successful. So everyone usually works "on tactical" a few days a week, completing other work on days that they're not on tactical shifts.

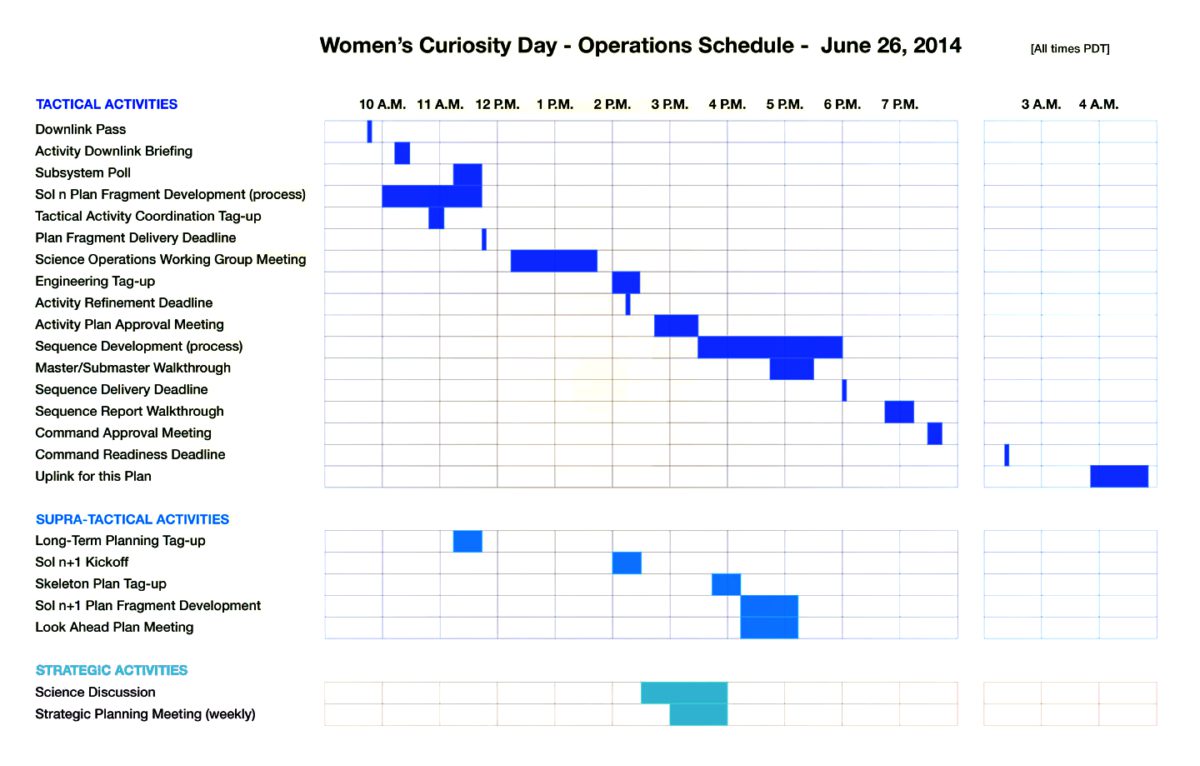

Here's a graphical view of the tactical planning schedule for Women's Curiosity Day, when they were planning the rover's sol 672. (Apologies for the text size on this graphic; you'll probably have to click to enlarge it.) The rover's sol 672 would actually begin just a little after 6 pm, Pasadena time; the first item in the schedule, the "downlink pass" just before 10 am Pasadena time, was the rover's evening communication session with a Mars orbiter, in which she returned to Earth the highest-priority data from sol 671. So this is a day that happened to be relatively well aligned with the Earth schedule, at least in California.

The first thing to take away from this graph is that there are actually three concurrent planning timelines for Curiosity. There is the tactical timeline (in which they actually develop the sequence of commands that gets sent to the rover), but there are two more planning efforts running in parallel: a "supra-tactical" one to begin to develop the "sol n+1" plan (in this case, the plan for sol 673), and a strategic planning effort (to set the longer term science-driven goals). Opportunity does not have such a supra-tactical planning effort. Curiosity is a far more complex beast than Opportunity; there just isn't enough time in a single planning day to scope and develop a set of commands for Curiosity, and there probably never will be, no matter how much more efficient they manage to make operations. They always begin developing plans an extra day in advance for Curiosity. That supra-tactical, sol n+1 effort needs its own staff of tactical planners, separate from the group that is planning sol n. There are people who have strategic, long-term planning responsibilities on Opportunity, but there are still a lot more people involved in a much more formal process for Curiosity than for Opportunity. These days the Curiosity strategic planning effort includes highly detailed pre-planning of Curiosity's future path, to maximize distance while minimizing wheel damage; I don't know for sure but don't think that Opportunity's path is preplanned in as much detail.

The other thing to note in the graph is that the schedule is relentless. I've been in mission operations and from the moment that the downlink teams get to work to the moment that the team approves of the command sequence, there is not a lot of time for chit-chat or reflection. Most people working tactical operations shifts eat their lunches during meetings as they all work together against the clock to create the rover's daily list of science-rich, risk-avoiding, triple-checked commands. It's exhausting work, but they're driving a laser-equipped nuclear-powered robot across another planet, so that's some compensation.

It's fascinating to explore all the different job descriptions on the Curiosity Women's Day microsite. There are separate pages full of profiles of all of the people who worked management, science planning, instrument teams, drive planning, and rover health. Mouse over any job title and you can see what each person does. Click on the little (i) symbol on each participant's photo to learn about the training and experience they received in order to be able to work on a NASA rover mission. One thing I learned by browsing those profiles: lots of the people fulfilling operational roles on the mission finished their education with Master's degrees rather than doctorates. Still, the higher-ranked team members mostly have doctorates, whether they're scientists or engineers.

The rover completed a drive on sol 671, and the plan for sol 672 was another drive. A Curiosity tactical planning day begins with assessment of the downlinked data. In the photo below you can see the engineers on the downlink team, at their stations, assessing the brand-new data from Mars. You can see the sol 671 data on the monitors behind them: there's a partial 3D Navcam panorama, made of a total of 20 photos, that includes the direction they planned to drive, and also the area nearby the rover that could be targeted with the Chemcam instrument. That represents the image data available for planning sol 672. Much of the rest of the data acquired on sol 671 (including the rest of the complete 360-degree panorama) would not be downlinked for another 5 hours, after an orbiter passed over Curiosity in the wee hours of the Gale crater morning. In charge is Tactical Mission Manager Beth Dewell, sitting at the station marked "Activity Lead."

The downlink side of the engineering team checks the health and safety of the rover, and catalogues the data that's been returned. On the science side, they look at the images they have available to figure out what, if anything, they can do with the science instruments with the limited time, power, and data volume available on a drive sol -- they're tightly constrained on all three counts. That conversation, among the scientists, about what they plan to do on that particular sol, happens mostly on the telephone, as most of the science team's participation in tactical planning now happens remotely. The one science-heavy meeting that contains a lot of people physically located at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory is the daily Science Operations Working Group (SOWG) meeting, where the downlink folks update the team on the status of the rover, the science people explain what their plans are, and the rover planners (also known as rover drivers) chime in with their opinions on choices of targets or other aspects of the plan. Once this meeting is over, the major shape of the rover's plan has been outlined, and gets split into pieces for engineers and science planners to fine-tune. Here's a photo from Women's Day of the room where they hold the SOWG meeting. Most of the people in the photo have tactical roles on the uplink (commanding) side of things, including the peanut gallery of rover drivers in the far corner. Not visible, on the phone, are representatives of every one of the rover's instrument teams. The SOWG is led by a scientist; science team members rotate into the responsibility of SOWG chair for a few days at a time. I think there are maybe half a dozen scientists who can be SOWG chairs. Pan Conrad, in the red shirt, is the Deputy PI on the SAM instrument and serving as SOWG chair for the day.

A lot of the work to fine-tune plans is done by science instrument teams developing the commands for their particular instruments. Here's a photo of the dedicated Curiosity operations area at Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego, California, where the women pictured here developed plans for all three Malin camera systems to be operated on sol 672.

And here's another instrument team, ChemCam, in the French Instrument Mars Operations Centre for MSL. They're located in Toulouse, France, working on the same Mars time as the mission team, but in an Earth time zone nine hours ahead. When the Curiosity mission shifted from Mars time to Earth time, tactical operations became much more painful for the French (ChemCam), Russian (DAN), and Spanish (REMS) instrument teams; rover operations happen very late in their days, so they're all working night shifts when they're on tactical operations. Here's a video, in French, about the work they were doing.

In their laboratories across the world, the instrument teams developed the sequences for Mastcam to shoot a context image for ChemCam to laser a rock, shot more Mastcam images after the drive (like this one), shot a MARDI image after the drive, shot more Mastcams for context for blind-targeted ChemCam laser zaps after the drive, shot a bunch of Mastcam images of the sky (these are for calibration purposes), and finished, about 10 minutes after local sunset, with a MARDI image of the soil beneath the rover. All that on a sol on which the rover drivers planned a 100-plus-meter drive. Not bad for a science-constrained sol!

In another room at JPL -- the one you can see through the open door of the SOWG room -- scientists and engineers on the supra-tactical team worked together to construct the skeleton of what would be the plan for sol 673. The room behind them is a fishbowl, acoustically isolated from the adjacent room; meetings are held in there that don't have a home anywhere else, and it's often used for "Tiger Team" meetings when there are problems to be worked. (You can see one of those intense meetings in this video.) This is mostly an engineering effort, especially when the planned sol is a drive sol; scientists won't get involved until they have images that they can use to target pre-drive observations, and that won't happen until sol 672 is over. On this day the supratactical effort was led by Supratactical Uplink Lead Ashley Stroupe, in the pink shirt in back.

While all the tactical planning is going on, there is strategic planning happening in yet another room at JPL. This particular meeting happens only once a week, though the effort of the individual workers involved is continuous. The strategic planning effort includes mission managers, scientists, and engineers, all developing long-term guidance on what the rover should do in order to fulfill its mission goals. Most of the people in this room also often work tactical roles, but they mostly can't participate in both strategic and tactical planning meetings on the same day. There are a lot of leaders in this photo; Project Manager Jennifer Trosper is at far left, and Project Scientist Joy Crisp is in the floral shirt near far right. Just to illustrate how people serve different roles on different days, Strategic Planning Lead Nagin Cox, in the ultramarine blue shirt near center, is today serving as Tactical Uplink Lead for planning sol 697.

Completely separate from mission operations is the testbed, where engineers test vehicles on Earth before they send commands up to Mars. There are two testbed rovers. Maggie is a duplicate of Curiosity, and Scarecrow is a body with legs and wheels only, which weighs the same under Earth gravity as Curiosity weighs on Mars. They didn't take pictures up at the Mars Yard during Women's Day, but they prepared four videos of engineers talking about their work there. Two examples:

Systems engineer Jamie Catchen talks about doing verification and validation with the sampling system:

And here is mechanical wheel wear Tiger Team member Amanda Steffy, talking about the work she's doing to help with the effort to break rover wheels on Earth in order to learn how not to break them on Mars:

So the "Women's Day" thing served primarily as an occasion for the Curiosity mission to explain all the different roles and responsibilities for people working on the mission. But I also think it's cool that it's possible to staff a flagship mission predominantly with women. I watched the replays of the 45th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing on Sunday, and there were almost no women to be seen; behind that lack of women in operational roles was a lack of women with the qualifications to fulfill operational roles, shut out of degree programs and job opportunities. But the one or two women who were there broke the path for many, many more to follow them. Now there are lots and lots of qualified women, and they're getting hired into NASA missions.

When I tweeted about Curiosity Women's Day when it happened a few weeks ago, many people asked me what the gender ratio ordinarily is in mission operations. So I asked Joy Crisp (one of two Deputy Project Scientists for Curiosity, and formerly Project Scientist for the Mars Exploration Rover mission, who acted as Project Scientist for Women's Day). I was also curious whether it usually takes 100 people to operate the rover on a given day, and how that's changed over the course of the mission. Here's what she said (and I'm amused by the scientific rigor and caveats in her response):

We had more operations roles at the start of the mission. Several of the roles that we had at the start of the mission have been combined and compacted since then. And at the start of the mission, we had a lot more people supporting operations in the testbeds doing verification and validation, and flight software people working on updates. I haven't done a complete inventory - that would be very difficult to extract from the records. What I can tell you is that the JPL "Full Time Equivalent" staffing level early in the landed mission was around 300, and now it's around 130.

Unfortunately it would take a lot of effort to figure out the answer the question "On an ordinary day, what fraction of the team is female"? What I did figure out was the total team counts and % women, which that might be an approximate guide to what the answer is likely to be. Not everyone on the science team directly supports operations - some focus on data analysis/processing/assessment, and some are much more active in operations than others.

Engineering team = 188 people, 46 of them are women (24% women)

Science team = 496 people, 138 are women (28% women)

There are 4 men and 3 women who are on both the Science & Engineering teams, so to calculate the total number of women, I add the two totals and subtract 3: Total MSL team size = 677 people (188+496-4-3 ), 181 of them (46+137-3) are women (27% women)

The short version: about one in four members of the Curiosity mission team is female. That number actually surprised me, because I'd had the impression it was higher. I'd have guessed it was at least one in three. Which may be my own observational bias operating!

So here's something to think about: on Curiosity Women's Day, when 75% of operational roles were filled by women, it was effectively a reversal of the usual gender ratio. What it felt like to be a man working among three times as many women on that day, is "normal" for women on the mission.

I was curious how much things have changed from the time Opportunity landed to now, on Curiosity. Since Joy has fulfilled project scientist roles on both missions, she was in a good position to answer. "In terms of the percentage of women involved, back when I worked on Mars Pathfinder and MER, the numbers have increased somewhat but not a whole lot. I found a personnel list for MER dated September 2006, and at that point in time, the MER science team was 24% women (46/188), which is somewhat lower than the percentage on MSL's current science team." That's a little disheartening. Joy continued: "We do have a lot of young women scientists and engineers on MSL, which is perhaps a sign that the next Mars mission will have an even higher percentage. The biggest difference between MER and MSL is the huge increase in complexity, and even stronger dependence on teamwork because of that complexity."

Joy closed by saying: "I was pleased that so many MSL women were enthusiastic about participating in Women's Curiosity Day, wanting to inspire young women by showing them the kinds of careers they might have. The men on the project were supportive of this special day too, and they helped us make it all possible."

The website is really fun to explore; I highly recommend checking it out. And if you know a kid, girl or boy, who's interested in working in space for a living, it's a terrific resource for learning about the kinds of work it takes to make a complex mission function, and what education you need to fulfill those roles.

The Time is Now.

As a Planetary Defender, you’re part of our mission to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth