A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 01, 2017

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Ventures Deeper into Perseverance

Sols 4807-4836

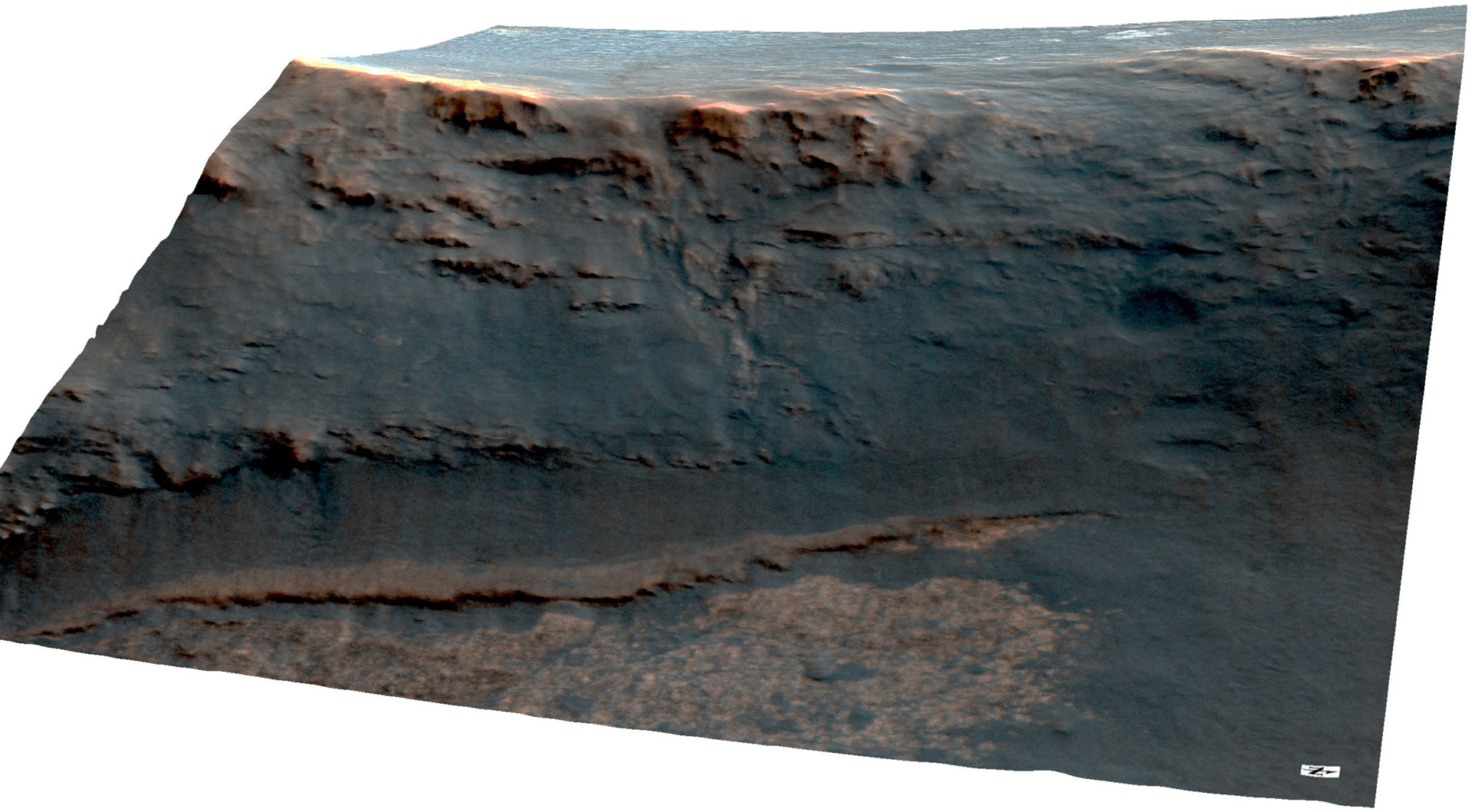

Along the western rim of Endeavour Crater, Opportunity forged onward in August vicariously taking the Mars Exploration Rovers team – along with a global contingent of mission observers all around Earth – downhill into Perseverance and deeper into a new chapter in this legendary expedition of the Red Planet.

“It feels great,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “We are really now in the thick of it for the first time.”

“It’s kind of like we’ve just walked into Town Square on Main Street USA at Disneyland and haven’t yet gotten to Space Mountain or Tomorrow Land,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

The first-ever exploration of a preserved valley system on Mars, the MER scientists’ research at Perseverance Valley promises to be among the mission’s most significant efforts. Whatever the team discovers here, it will add to our knowledge of Martian geology and to the water story of Meridiani Planum, where Opportunity has been exploring since landing in 2004.

How this unique geological feature came to be billions of years ago is a mystery. The valley, which cuts through the crater’s rim, hints that it may have been carved by water, or possibly ice or muddy debris flows, or even perhaps by ancient Martian winds. The veteran robot field geologist and her team are here to find out.

In August, Opportunity drove into “the first terrain where there’s a lot of local topography that might be indicative of the process that formed the valley,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis.

After experiencing an unexpected reboot, the robot had put herself into automode in late July, at the beginning of solar conjunction when Mars orbits around to the other side of the Sun and out of view from Earth. So, during the first Martian days or sols of August, as the two-week mandatory communication blackout period ended, Opportunity followed commands to take herself out of the safe mode and then got to work.

Parked on a gentle slope just inside the valley, the rover spent a few sols taking pictures of her site and conducting a close-up inspection of a small rock there named Parral. Then, the robot took off and the venture into Perseverance really got underway.

Despite suffering an issue with her left front steering wheel in June that required the ‘bot change her driving strategy and some rough, deceiving terrain, Opportunity pulled up to the first chosen science station in the valley without much ado. There, she spent a couple of weeks documenting her surroundings and the site’s morphology with her cameras.

The winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars where the MER mission is exploring occurs in mid-November, but the robot began feeling the seasonal effects in August. Like on Earth, the winter Sun doesn’t shine as long each day and rises and sets lower on the horizon, and the temperatures drops to beyond freezing levels. To meet her current operational demand, Opportunity began devoting two or more sols per week just to recharge her batteries.

With the Martian winter to take hold soon, the team’s concern about the rover is ever-present. “Winter is our most threatening season on Mars,” reminded Callas. “Not only do you have less energy, but you actually need more energy because it’s colder and it takes more energy to keep the rover warm. And, it’s damn cold,” he said.

The MER ops team has been monitoring a low temperature, recorded around 5 a.m., local Mars time, of -87 degrees Celsius [-124.6 degree Fahrenheit] and a high temp at about 1:30 in the afternoon local Mars time, of 2 degrees Celsius [35.6 degree Fahrenheit]. “That’s an almost 90-degree Celsius [194-degree Fahrenheit] temperature change in one day,” Callas pointed out.

“This winter is going to be tougher than last winter,” said MER Chief of Engineering Bill Nelson, of JPL. For starters, it will be the MER mission’s eighth Martian winter, amazing when you consider few people believed Opportunity or her twin Spirit could even survive their first winter in 2005. Moreover, both the rover and the sky are dustier than in most previous winters.

Juggling the science and engineering requirements with available power is intense, complex, and, stressful even for the most experienced and lauded Mars rover ops team in the world. And already, this winter “is not being too nice unfortunately,” said MER Rover Planner Paolo Bellutta, a member of JPL’s Robotics Technical Staff and Senior Member of the Lab’s Vision Group, who has been charting Oppy’s routes since Victoria Crater.

The MER scientists’ research in Perseverance is centered on imaging the morphology of the Perseverance Valley system and less focused on examining rocks and soil. That presents a conundrum because taking pictures takes energy and good lighting. “The latter part of the day is the best time for imaging, but the Sun is too low in the sky then,” said Arvidson. “If we get up and image around Noon, then we have to use a lot of energy waiting for Odyssey to come by late in the day and there’s not that much energy to go around.”

The energy constraint is compounded by Opportunity’s loss of her Flash or long-term memory a couple of years ago. The rover has no choice but to store her day’s work in RAM, which is volatile memory. That means the robot must send everything to one of the orbiters, Odyssey, her mainstay, or the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), before she shuts down for the night or the data will be lost.

Nevertheless, with the support and guidance of her human colleagues on Earth, Opportunity maintained decent power levels throughout the month. The solar powered rover generally produced upwards of 300 watt-hours, a level slightly less than one-third of her full capability on landing with clean solar arrays and enough to keep roving and working while braving the first strains of winter.

“It’s not bad,” said Callas. “It’s just that we’d love to be able to do more because we can do more. We have this great asset on the surface of Mars and right now energy has been our hamstring.”

For most of the MER engineers, the perspective is a bit different. “While the planning team struggles to determine what they can do with the energy they have, my perspective is: ‘Yay, we’re still over 300 watt-hours!’” said MER Power Lead Jennifer Herman, who was happily breathing a little easier. That’s way better than it could have been.”

During the third week of August, Opportunity roved on to the second science stop downhill. Once her work here is finished, she will continue the journey down the valley and to the floor of Endeavour Crater, some 170 meters or 186 yards, stopping for research at five more planned science stops along the way. “We’ll drive downhill at about 20 meters a clip and then spend time at each of those places doing 360-imaging with Navcam and targeted Pancam imaging, and when targets present themselves doing some close-up work,” said Arvidson.

As has become usual during the Martian wintertime, Opportunity will maintain her energy and maximize her power on her treks downhill by using the “lily pad” strategy. This tactic, which the team first used during Spirit’s winter climb up Husband Hill in 2005, involves directing the solar-powered rover from one north-facing slope to another where she can position her solar deck to the north where the Sun rises and falls in the sky during the Martian winters and soak up as much of sunshine as possible for power production.

Using orbital images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO and the best images Opportunity can take on the ground, the rover planners (RPs) work with the science team to pick the best north-facing slopes. “Like a frog hopping from lily pad to lily pad, we ‘hop’ from one area of good northerly tilt to another, because in the wintertime on Mars, a good northerly tilt means good array energy,” said Nelson.

The team is hoping for a gust of support from Mars. “If you look at the trends from the past years, we usually get some dust cleaning around winter solstice or a little before,” said Herman. And the rover’s location in the valley places her in a good position to greet any winds that whip up from the crater floor.

Opportunity’s new driving strategy (using only her rear wheels to steer and turning like a tank) along with the bitter cold and tenacious terrain has presented a new challenge for the rover, but she continued to display her MER determination. “We will come up with another ‘rabbit out of the hat’ to minimize stress to the vehicle,” assured Bellutta. “We are still debating how to do that and spent a couple of days driving the testbed in terrain similar to Perseverance Valley to analyze what each command would do to the vehicle on Mars.”

For now, Opportunity is looking all around and sending home as many images as possible. “The rover is doing fine, the team is doing a great job, and we’re just going to keep at it,” said Squyres. “We’re very happy with the way the rover is performing right now,” added Nelson. “I expect that she will chug through the winter and do a lot of good science along the way.”

Deep Dive into August 2017

When the Sun rose on August and Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was stuck in automode. The robot had experienced an unexpected or warm reboot just as the mandatory solar conjunction communication blackout began in late July.

On August 2, 2017, the rover's sol 4808, Opportunity's human colleagues at JPL sent commands to restore the robot's "homeostasis." The following sol, the rover resumed normal science activities. “Everything looked fine,” said Herman.

Opportunity promptly began two sols of studying a cobble or small rock the team named Parral. She took a set of Microscopic Imager (MI) mosaics of the cobble a set of Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) offset placements on the same target to analyze its chemical composition.

Parral is named for the stop on the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (The Royal Road of the Interior Land). When the rover entered Perseverance, the team changed its naming theme to stops along this old, 2,560-kilometer (about 1,591-mile) trade route between Mexico City and San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico.

In between her research assignments on Parral, Opportunity focused her Navigation Camera (Navcam) and her stereo Panoramic Camera (Pancam) “eyes” that enable her to look out across the landscape in 20/20 vision to visually document some of the views and the morphology around her and complete some of the science lost because of being in automode throughout solar conjunction.

The plan made weeks ago remained the same. The robot would drive through the valley during winter, stopping at lily pads or northerly tilt terrains along the southern wall of Perseverance. “Lily pad is not a technical term,” noted Callas. “But generally people understand what a lily pad means.”

On Earth, lily pads are little floating islands that frogs use to hop onto for rest or to travel across a pond or body of water. On Mars, ‘lily pads’ are locations where the terrain is tilted sufficiently to the north for the rover to bask the Sun and maximize the illumination on the rover's solar panels.

While some MER team members cite the Earth pond analogy as the source for the term, others, including Bellutta, remember the name entering their lexicon as a result of the application that the ops team uses to determine favorable slopes. “The application uses green to highlight terrain that is tilted to the north,” Bellutta explained. “They look like lily pads.”

Wherever the term originally came from, it stuck. The team deployed the lily pad strategy during the mission’s first winter in 2005 when Spirit hiked Husband Hill. The strategy for maximizing power production throughout the brutally, “damn cold” season has worked beautifully ever since. But it can only work when there are north-facing slopes within reach.

When Spirit was unable to get unstuck from sandy soils at Home Plate and on a good northerly slope in 2010 during the MER’s fourth winter, it was in all likelihood what initiated her demise. When she failed to respond during the ensuing year, NASA, in May 2011 declared her mission over. Spirit is now a monument to Mars exploration, standing guard at Home Plate in Gusev Crater, perhaps to be visited by human explorers at some point in the future.

Meanwhile on Earth, the MER officials formed the winter planning team. “We do this every winter so that the science and engineering teams can formulate a strategy for the winter together,” said Herman.

Usually at one of these meetings, Herman presents predictions for the rover’s energy outlook. She makes recommendations for how many degrees the tilt of the rover and her solar arrays need to be in order to get enough energy to run the ‘bot’s internal survival heaters, and how much more of a tilt it will take for the rover to have enough energy to effectively conduct some scientific research and rove on.

With Herman’s tilt recommendations, the science team presents maps based on orbital imaging, mostly HiRISE images, and the tilt information to the rover planners (RPs). Together, they choose a slope that looks like it offers a good view of the surroundings and, ideally, some good targets within rover reach.

Once Opportunity emerged from conjunction and was back to sending home telemetry, Herman reviewed the data and worked to adjust some of the assumptions she had previously made in the power model. “The atmosphere was a little bit dustier than I was expecting,” she noted. “Unfortunately, that means less sunlight than I was expecting. Actually, the sky was the dustiest that Opportunity has ever seen this time of year. Based on that, I had to increase my assumptions and that lowered the power estimates.”

But these predictions are tricky and complicated and in the midst of her analysis, Herman also uncovered good news. When she looked at the dust model that keeps track of how much dust is on the rover’s solar arrays, it appeared that the arrays weren’t accumulating as much dust as she had anticipated, “possibly because the dust is stuck in the atmosphere,” she suggested. “It’s a bigger hit to your predicted energy to have dust on the panel than to have it in the sky. So in the end, my recently updated estimates predicted slightly more array energy,” she said.

Herman had previously recommended that Opportunity would need to park on 15-degree north-facing slopes to survive, but in August she changed her recommendation. “Ten-degree slopes appear now to be enough to survive winter,” she said. “Of course, a 15-degree tilt to the north would provide even more energy per sol.”

As for all that dust still lingering in the atmosphere?

The MER mission measures the dust in the sky with the Pancam, using near-daily images of the Sun to determine optical depth or what the team has forever referred to as Tau. “The measurement is influenced by dust accumulating on the camera itself, which can be mistaken for dust in the sky in any individual measurement,” said MER Science Team member Mark Lemmon, Associate Professor and atmospheric scientist at Texas A&M University. “Over time, the effects of the dust on the camera can be measured, and the calibration can be adjusted to improve the measurement of dust in the sky,” he said.

“Dust is slightly on the high side, maybe even back to normal in the last week or two,” Lemmon continued. “But that is a science result, based on a recalibration I've just done,” he explained.

Lemmon calibrates Pancam for taking the Tau and typically checks it three or four times a year. “Any seeming change has to stick around for a while before I believe it,” he said. “Now I have a change.”

Basically, he said, there has been a slow accumulation of dust on the Pancam optics. “It comes and goes. The calibration puts dust on the window (in a modeling sense), and takes it out of the sky. Without the calibration, dust on the window obscures light and is interpreted as dust in the sky.”

Lemmon is quick to point out that he does not change the ops calibration lightly. “That gets coordinated with engineering,” he said. “Energy accumulation does not change. So when I change window dust on Pancam [moving it up], I change Tau in the opposite direction or down, and that [in turn] changes the estimated dust on the arrays the other way or up.” In other words: more dust, lower dust factor.

“Rather than having it look like a sudden change to both weather and dust factor, we have to arrange it to fit nicely in the ops schedule,” Lemmon said. “The bottom line is that dust is everywhere: on the camera, in the sky, and on the solar panels. We try and book-keep where it is, but the raw power numbers trump that for operations.”

Through all the Martian dust and the coming winter, Opportunity will rove on and work her way down Perseverance Valley, “hopping” from lily pad to lily pad. The MER team has calculated and tentatively decided that she will stop at a total of seven science stations about 20-25 meters apart down the 170-meter (186-yard) length of Perseverance Valley. “Every station is a lily pad, based on HiRISE data, but not all lily pads are stations,” said Nelson. So the rover will be making pit stops on lily pads in between science stations.

Even hopping from lily pad to lily pad though won’t be enough to ensure Oppy can rove and work throughout the mission’s eighth winter. With the temperature dropping and winter moving in, the rover also began incorporating rest sols into her schedule in August.

During these "recharge" sols, Opportunity sleeps throughout the day waking only for the morning Deep Space Network X-band session and the afternoon Ultra High Frequency relay pass with Odyssey or MRO. These recharge sols will be a regular occurrence through the Martian winter.

The robot field geologist spent her Sol 4812 (August 6, 2017) recharging in preparation for her trek to her first science station inside Perseverance. The plan called for Opportunity to drive away from Parral and the solar conjunction parking site on Sol 4813 (August 7, 2017) and head for the first official science station in Perseverance Valley.

“Drive time was limited by energy and the rover wasn’t expected to reach the station, but was expected to stop on a Sun-facing slope or lily pad,” said Nelson.

Turned out, Opportunity’s drive stopped short after 3.55 meters (11.64 feet) when the rover encountered some difficult terrain while turning. “The rover was doing a large turn in place and the onboard fault protection software detected that one of the drive actuators was drawing too much current and stopped the active command,” explained Bellutta. “We determined that this was due to the combination of not being able to steer the left front wheel and the very hard terrain we are currently traversing.”

While the surface appears to be “smooth and polished,” as Bellutta described it, in fact, he said, “it has a very rough finish, similar to rough concrete or asphalt. While this provides good traction, it is quite harsh on the non-steering wheels.”

“The terrain has some peculiar characteristics to it,” said Squyres. “We saw unanticipated high wheel currents, not crazy high but higher than we all sort of expected. And we’re also finding that the Visual Odometry (VisOdom), this process we use to figure out exactly where we are, is not working very well in this terrain.”

Though somewhat mechanically stressed, Opportunity carried on like always, continuing her drive the next sol, bumping 1.21 meters (3.96 feet) on Sol 4814 (August 8, 2017). “The vehicle completed the drive using curved arcs and was much happier and thanked us with much lower currents,” said Bellutta. And she reached her goal, an intermediate lily pad.

While the temperature outside was dipping as low as -87 degrees Celsius [-124.6 degree Fahrenheit], the robot was warmer inside. Opportunity’s internal temps, ranged from -55 to -34 Celsius [-67 degree to -29.2 degree Fahrenheit].

“This is our second winter in RAM mode,” said Callas. Working in RAM mode means the rover has to stay awake until the comm pass to get the day’s data to Earth. “Last winter was pretty tough because of that and this winter the dust factor or the amount of dust on the solar arrays is a little bit worse than last year.”

“To mitigate that as best as we can, one of the things we’ve done is request more MRO passes,” said Callas. “The MRO passes are earlier in the afternoon, at 2 o’clock in the afternoon versus 6 o’clock which is when the Odyssey passes are.”

Mars Odyssey is the MER mission’s primary downlink to Earth, but by the time it swings by, it is often well past sunset and that makes for tricky scheduling. “Moving Opportunity’s activities to late in the day means colder temperatures and bad lighting conditions, said Bellutta. That impacts the rover’s ability to get the kind of good, crisp images on which the team relies for moving forward and for science.

Downlinking through MRO on the other hand makes life on Mars in the winter easier for Opportunity. “If we have an MRO pass, we can go to sleep four hours earlier and save that energy,” said Callas “We can’t get MRO passes everyday, but we are hoping now to get them every other day.”

“We expect to have to deal with all of these restrictions well past Martian winter solstice in November, likely through December or maybe January of next year,” said Bellutta.

Added MRO passes will help a lot. As it is now, during every multi-sol plan moving forward and through winter Opportunity will have a recharge sol, “just because there’s so little energy getting through the solar panels into the battery for the rover to operate,” said Callas. “We want to keep active on the surface, so you know it’s not so much a health and safety concern for us as having the energy we need and want to be scientifically active during this period.”

So Opportunity slept in on Sol 4815 (August 9, 2017), building her battery charge for the drive planned for the next sol.

The rover woke up on Sol 4816, revved her solar-powered ‘engine,’ and put 10.54 meters (34.58 feet) in the rear view mirror, stopping as planned on the north-facing slope or lily pad chosen as the first science station. The wheel currents after this drive were within nominal ranges and that made everyone on the team happy.

Opportunity promptly did a Quick Fine Attitude (QFA) to remove accumulated drift in the her inertial measurement unit (IMU or gyros). Basically, this procedure corrects any error in the rover's knowledge of its attitude relative to the Sun or, in other words, enables the engineers to confirm her exact location. Then, the MER science team assigned their geologist various tasks on an extensive remote sensing campaign.

The robot first took some Navigation Camera (Navcam) images and then during the ensuing sols continued to collect Panoramic Camera (Pancam) and additional Navcam images for the MER scientists to use in characterizing the morphology there.

As the rover makes her way down Perseverance Valley and to the floor of Endeavour Crater, the MER scientists and team are approaching the journey in a “kind of a workman way,” said Arvidson. Under the assumption that once Opportunity moves on from a place, she won’t be going back to it, the goal is for the ‘bot to thoroughly shoot and document each science location very carefully before moving on to whatever is next.

The MER Science Team has had its working hypotheses for months and now it’s a matter of the rover taking all the images, studying what she can up close, and getting the data down to Earth.

Opportunity took a day to recharge on Sol 4819 (August 14, 2017), powering back up for more imaging activities during the next two sols. In the valley, the prime directive for the robot field geologist is to extensively document the local morphology at each location so that the team can create a 3D digital elevation model of the entire valley.

By mid-August, the rover was working that objective at this first station within the valley. On Sol 4820 (August 15, 2017), Opportunity shot her day away with her Pancam and Navcam. In addition to morphology imagery, she also took images the team needed to scout the next drive path and the next best lily pad and later worked in some atmospheric or Tau observations.

Beyond having to work within the confines of RAM mode and the dropping temperatures, Opportunity is navigating her way downhill and however gentle the slope, the rover can only see about 20-25 meters ahead. Images from the HiRISE camera onboard MRO have helped guide the MER mission since it became operational back in 2006, but the team does not rely solely on that orbital data.

“We have some indications from the HiRISE camera that the valley should have many of these [north-facing] locations, but we need to locate them using the rover’s onboard cameras,” said Bellutta. “While science has indicated the general area that they would be interested in observing, the terrain is sort of in control here.”

Opportunity used her Pancam on Sols 4822, 4823, 4824 and 4825 (August 17, 18, 19, and 20, 2017) to collect Tau measurements, as well as pictures of local outcrop, panorama images of the north valley and the valley proper, sky thumbs, and horizon surveys. She also took some images with her Navcam. And on Sol 4826 (August 21, 2017), the robot rested and recharged.

The next sol, 4827, Opportunity took more Pancam Tau measurements and more Pancam images and then she really rested. From Sol 4828 to Sol 4830 (August 23-25, 2017) the robot concentrated on recharging and boosting her energy for her upcoming drive to the second science stop on her journey through Perseverance to Endeavour’s floor.

At the first science station on the journey, the valley looks texturally like so much rubble. “There’s not a lot of fine grained sand or dust and it looks windswept,” said Arvidson. “There’s a little bit of scouring, and the sense of the scour is that the winds are pointing uphill, which is not surprising. Whatever generated this valley in the past, it certainly been sculpted, to maybe tens of centimeters scale, by wind for sure.” But, he qualified: “We’re still near the top of the valley, the smooth part.”

“We are excited,” said Herman. “My original recommendation was to be at or near a good northward tilt by the middle of September. We have already done that, so we’re ahead of schedule.”

On Sol 4831 (August 26, 2017), Opportunity headed out, roving northeast (about 65-66 degrees from north) toward the next lily pad and the second science station farther into the valley. She stopped mid-drive to take some pictures with her Pancam and Navcam, and after logging 25.16 meters (82.54 feet) the rover stopped and, as usual after driving, took more images. Then, she spent the next two sols, 4832 and 4833 (August 27 and 28, 2017), recharging.

Turned out, so ready to rove this robot apparently is, she zipped right past her stop. “We had to blind drive [on this sol] for power reasons and we missed the lily pad,” said Bellutta.

“Lack of trackable features caused the camera-based Visual Odometry (VisOdom) to fail, and that resulted in slip that veered the rover away from her target,” said Nelson. “And the rover ended up overshooting.” When Opportunity came to a stop, she was at a tilt of around 6 degrees, he said, “power limiting but not to unsafe levels.”

“The way we do these drives sometimes is we set the drive to terminate when the rover senses it has a northward tilt of some value, like 10 degrees,” said Squyres. “We never reached that 10-degree limit on this drive and we experienced more side slip than we anticipated. We just missed the lily pad.”

Perhaps Opportunity drifted off course because she was anxious to chalk up her 45th kilometer, which she did with that side-slipping drive that turned her odometer to 45,013.96 meters or 45.013 kilometers (27.970 miles). The drive also put the longest-lived Mars rover just 43.45 meters (142.55 feet) away from breaking the 28-mile milestone, noted Nelson.

Once the MER ops team members confirmed that Opportunity missed her lily pad, they scheduled the short drive back to it for Sol 4834 (August 29, 2017). “The vehicle drove backwards uphill at quite a steep slope without too much trouble,” said Bellutta. “Oppy is back at a northerly tilt of about 12 degrees!”

The "commute" was just 4.22 meters (13.84 feet) and the rover ably parked herself on the chosen lily pad that is the second science station, wrapping August with a grand total of 45,018.18 meters (45.018 kilometers, 27.973 miles) on her odometer. The robot spent the next sol, 4835 (August 30, 2017) recharging.

Despite the inevitable aches and pains of aging, Opportunity is driving remarkably well and shooting and returning “picture postcards” just like she always has. The new drive strategy “really hasn’t cramped our style much yet,” said Squyres. “We have steering actuators in the direction we’re going and it works just fine. I can imagine some situations where it creates an issue, but the rover drivers are pretty cagey and they’ve done a good job of adapting to it.”

That backward drive up the hill was “like driving a car,” Squyres said. “Realize too that there’s something we can do that you can’t do with a car, and that is run the wheels on one side in one direction and the wheels the other side in the other direction and turn like a tank turns or a bulldozer turns,” he added.

“There’s so much functional redundancy built into the way this vehicle operates, so many different ways of getting a given job done, that if you sort of lose one way of doing it you’ve still got others,” continued Squyres. “So we have not suffered significantly from the loss of that left front steering actuator. We are very fortunate however that that wheel is pointed straight ahead and with it pointed straight ahead, it’s not that big of a deal.”

With the drive to the second science station, Opportunity is probably past the point of no return. But maybe not. “If for some reason we decided we had to claw ourselves out of this thing, I bet the rover could do it,” said Squyres. “But there’s no reason to do that. Our intention has always been to do a one-way drive down, working our way down incrementally.”

Truly an incredible robot, Opportunity, from all appearances, is managing just fine thank you, and the RPs are determining the best “workarounds” and techniques for keeping the rover unstressed, mechanically speaking.

“The rover seems to be driving well, except that the lack of steering actuators in the front makes the rover life a bit miserable,” said Bellutta. “We spent a couple of days driving the testbed rover [at JPL] in terrain similar to Perseverance Valley to analyze what each command would do to the vehicle on Mars. The different gravity field here on Earth makes things a bit more complex obviously.”

Nevertheless, the team’s optimism remains high, just as it almost always is. “I think things are looking good and the RPs achieved some good tilts,” said Herman. “If Meridiani behaves the way it has every other Mars year, we should expect to have some dust cleaned off the arrays in a few months. Cleaner arrays would allow the tilt restriction to be removed. We’re all crossing our fingers for that.”

Although Opportunity did start to experience the limited power anticipated during Martian winters and was somewhat challenged in August, she continued for most of the month to produce power levels a little higher than expected, said Nelson.

Throughout the month, the solar-powered rover produced upwards of 300 watt-hours of energy, while the Tau fluctuated from 0.723 to 0.593 to 0.683 and 0.608. The rover’s dust factor on her solar arrays remained fairly consistent fluctuating through the month from 0.531 to 0.511 to 0.518 and 0.516. As August gave way to September however, Opportunity’s energy dropped a bit, to 282 watt-hours.

A Martian gust that clears some accumulated dust would be a gift to be sure, but, said Nelson, “we’re still able to drive and we expect to be able to carry out our winter campaign without being particularly inconvenienced beyond what we already expected.”

Opportunity wasted no time in getting to work at her second science stop in Perseverance. Using her Pancam and Navcam she began by collecting more of the environmental imagery that is a hallmark of the mission. “Maybe we will be sniffing the terrain using the APXS and taking some close-up with the MI,” added Bellutta.

In coming sols, despite some rumbles about roving on, Opportunity will stay put at this science station, at least through the American Labor Day weekend. She will spend most of her worktime visually documenting the valley morphology and her surroundings now that she and the MER team are at long last “in the thick of it,” as Squyres put it.

Once Opportunity has completed taking those images and recharged some, the team will command her onward, to the next lily pad and the third science station.

This Martian winter just may be the MER mission’s first winter of discontent and discovery. The rover’s colleagues on Earth will be with Opportunity every rove of the way, just as they have been since she first landed in January 2004.

“The scientists care a lot about what we engineers say about the rover being safe and we care a lot about getting the rover to those places the scientists want to study,” said Herman.

It’s true. The veteran, Mars-exploring humans on this team are onboard, by and large, because they want to be. They could have moved on, and indeed many are working multiple missions. But the caring, the loyalty, and that devotion to their robot field geologist is the X factor that grounds and inspires the intangible magic of MER.

“I’ll be glad when winter is over. We’re tight on power as we always are at this time of the year and we’ll be at this for a while, but Opportunity is doing just fine,” said Squyres.

“We are tempered by the fact that winter is coming,” said Callas. “It’s kind of being in the upper Midwest or Northeast where during the wintertime you keep your head down and your scarf tied around your neck and just keep stepping forward. It’s little bit of that now with this energy limitation. It’s making each step forward a little challenging right now.”

Even so, Callas added: “This rover has had to adapt to change in the past and the rover sort of has a mindset that it will do what it has to do to keep going. I think the whole team continues to be impressed with the fact that this rover keeps going.”

Generally, the scientists are taking in the all the new views inside Perseverance and leaving scientific assessments for later. There’s not much to report right because we’re doing imaging,” said Arvidson. “But we’re in the groove. The next several months will be important though because we will be traversing right down the center of the valley and through all the textures we’ve been talking about. Are they channels and bars? Are they just wind-eroded bedrock? What the heck is going on here?”

Opportunity will need to stay on north-facing slopes probably through early January unless there’s a dust-cleaning event. “That timing however meshes because it's going to take about that long to do the science campaign all the way downhill,” said Arvidson. “We won’t have the observations needed to allow us to test the various hypotheses until December, maybe early January. So everything’s good,” he summed up at August’s end.

This veteran rover may be “an old gal,” reflected Bellutta. “But Opportunity still does her job and she is still relevant and engaging.”

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth