Emily Lakdawalla • Feb 07, 2006

The Orbital Dance of Epimetheus and Janus

Saturn is surrounded by a crowded family of rings and moons, and two of those moons -- Epimetheus and Janus -- orbit Saturn so close together that it seems as though their different orbital speeds should make them crash into each other. But due to the complex interplay of their mutual gravitational attraction and their very slightly different distances from Saturn, they never get closer than about 15,000 kilometers (9,000 miles) from each other. Instead of crashing, they exchange orbital positions in a gravitational do-si-do once every four years, in a dance that takes 100 days to play out. Cassini was able to observe the swap once during its primary mission, on January 21, 2006 at 02:24:57 UTC.

Here is how the dance works. Epimetheus and Janus are small, irregularly-shaped moons with diameters of about 120 and 180 kilometers (about 75 and 110 miles), respectively. Both are on slightly eccentric orbits around Saturn. Their orbits around Saturn differ in size by only 50 kilometers (30 miles). When Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004, Epimetheus was the inner of the two satellites. Because it was closer to Saturn, Epimetheus traveled at a faster angular rate than Janus, so inner Epimetheus slowly, inexorably caught up to outer Janus. As the two approached each other in their orbits, Epimetheus tugged on Janus from behind as Janus tugged on Epimetheus with equal and opposite force.

The mutual tugging caused them to exchange angular momentum. Epimetheus gained momentum and rose in orbit as Janus lost an equivalent amount of momentum and fell. Because Janus is four times more massive than Epimetheus, it fell four times less than Epimetheus rose. The switch of orbital altitudes made Janus -- still ahead of Epimetheus in its orbit -- the faster of the two. As a result, Janus crept ahead, and will continue to do so until catching up with Epimetheus again in 2010. The diagram below explains the behavior schematically. The closeness of the two moons is exaggerated -- Epimetheus and Janus never approach closer than about 15,000 kilometers (9,000 miles) from each other, roughly 100 times their diameters.

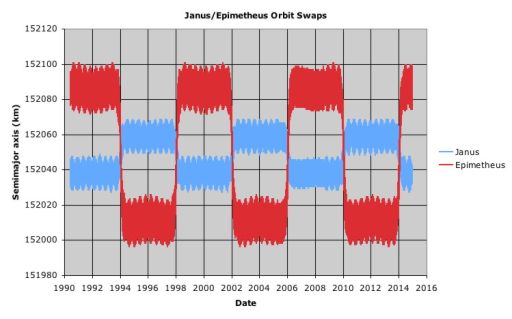

The graph below shows how the orbital distances of the two bodies will change over the next several years.

Credit: NASA / JPL / David Seal

Changing orbits of Janus and Epimetheus

This graph displays the orbital distances of Saturn's small moons Janus (blue) and Epimetheus (red) over 25 years. The two moons occupy very nearly the same orbit and swap orbital positions from Saturn once every four years. Because Janus is larger than Epimetheus, the exchange of orbital momentum changes Janus' distance from Saturn less than it changes Epimetheus'.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

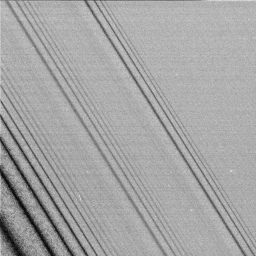

Ultra-close view of Saturn's rings

Just after entering Saturn orbit on July 1, 2004, Cassini turned to capture the closest views it will ever achieve of Saturn's rings. The views were from the north (shadowed) side of the rings. This image, of the outer part of the A ring, contains density wave structures excited by the gravitational influences of the tiny moons Janus, Pandora, and Prometheus. The view spans about 207 kilometers.But, Janus and Epimetheus aren't only tugging on each other. They also tug on the particles in Saturn's rings. All of Saturn's moons create complex wavelike structures within Saturn's rings, which make them appear finely corrugated. The waves are excited because of orbital resonances between ring particles and moons -- at certain distances from Saturn, ring particles and the moons have orbital periods that are integer ratios of each other, so they meet and part and meet again over time, and repeated, rhythmic gravitational tugs by the masses of the moons accumulate to change the orbits of the ring particles. The wavelength of the structures, how quickly they damp out, and other parameters are very subtly responsive to the orbits and masses of the moons.

Understanding the structure of the rings and their relationship with Janus and Epimetheus requires two sets of observations: finely detailed scans of the structure of Saturn's rings, both before and after the swap, and "movies" of Janus and Epimetheus mutual events against a background of bright stars. One such movie is below. This "mutual event" of Epimetheus and Janus as observed by Cassini took place on November 29, 2005. Epimetheus and Janus do not actually pass each other; the apparent crossing is caused by Cassini's shifting point of view as it traveled on its own orbit at a distance of about 1 million kilometers (600,000 miles) from the pair.

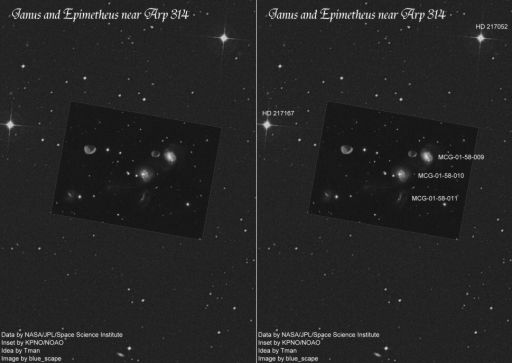

In addition to Janus and Epimetheus, it is also possible to see a few bright stars moving in the background of the animation. Here, an individual frame from the animation, with its background subtracted, is superimposed on a star field:

Credit: Data: NASA / JPL / SSI / KPNO / NOAO; image by Peter Greutmann and Nico Schmidt

Janus and Epimetheus against a star field

On November 29, 2005, Cassini captured a "mutual event" animation of Janus and Epimetheus. Several background stars were visible in the raw images, so amateurs Peter Greutmann and Nico Schmidt cut Janus and Epimetheus from the Cassini raw images and superimposed them on an image of the star field from an NOAO telescope.In a particularly beautiful animation produced by enthusiast Peter Greutmann, the entire animation, with background subtracted, is here superimposed on the same star field.

Credit: NASA / JPL / SSI / KPNO / NOAO / Animation by Peter Greutmann

Janus and Epimetheus ’mutual event’ against a star field

On November 29, 2005, Cassini captured a "mutual event" animation of Janus and Epimetheus. Janus and Epimetheus do not actually pass each other in their orbits; it is Cassini's motion that makes them appear to. Several background stars were visible in the raw images, so amateur Peter Greutmann cut Janus and Epimetheus from the Cassini raw images and superimposed them on an accurately scaled and oriented image of the correct star field from an NOAO telescope.Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth