Casey Dreier • Apr 15, 2014

The End of Opportunity and the Burden of Success

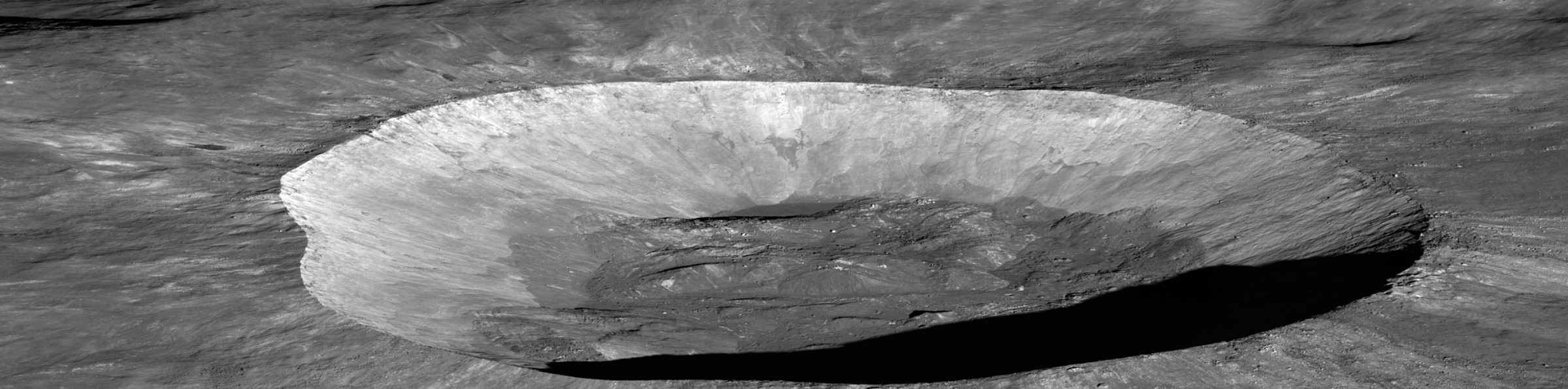

Lately, multiple news outlets have reported on the possible cancellation of the Opportunity rover, the longest-running Mars surface mission in history. Less reported, but equally important, is that NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), currently orbiting the Moon, is in the same situation.

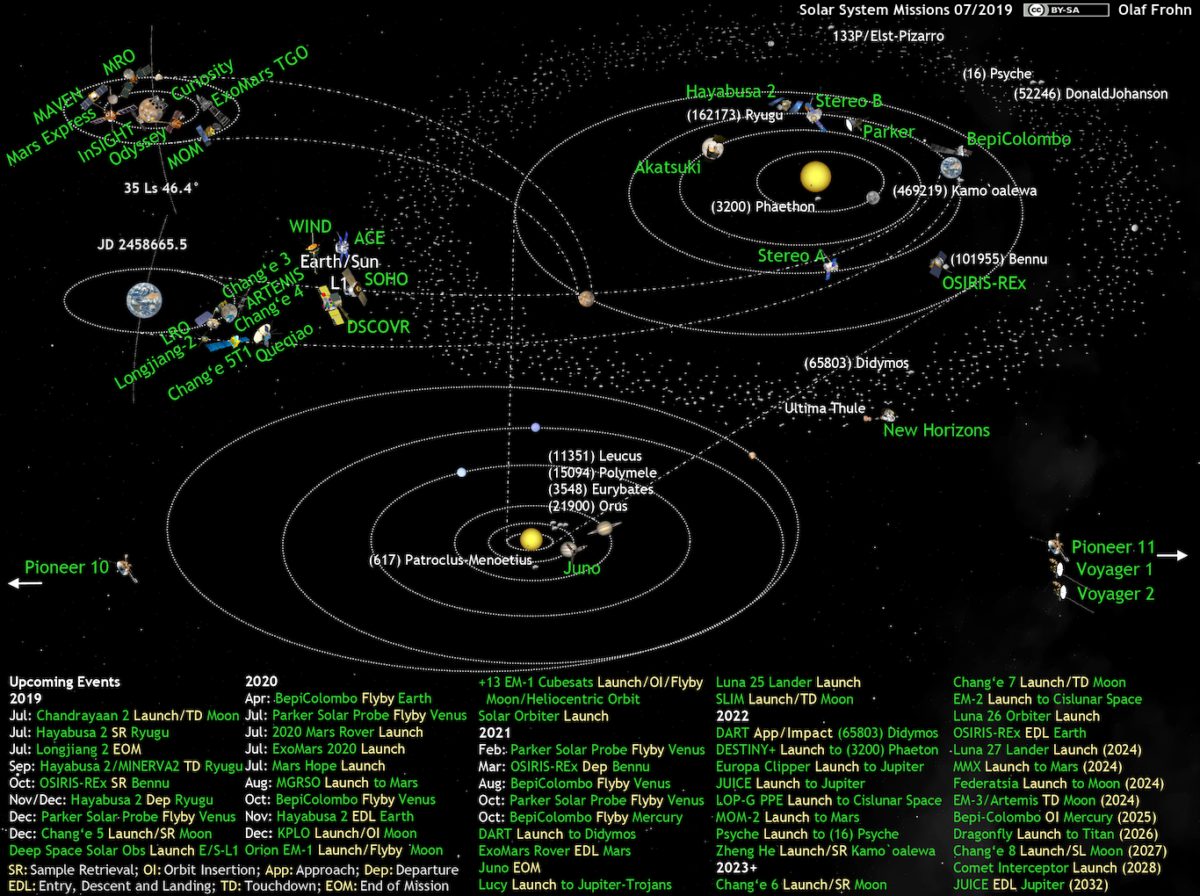

Opportunity is currently exploring the outcrops around Endeavour Crater in this artist's conception. You can follow the mission with our monthly MER Update.

Opportunity is currently exploring the outcrops around Endeavour Crater in this artist's conception. You can follow the mission with our monthly MER Update.NASA / JPL-Caltech

Most people find this mind-boggling. The cost to run both missions is around $25 million dollars per year, about 2% of the budget of NASA's Planetary Science Division, and approximately 0.15% of NASA's total budget (I'd plot this, but the amount is too small to be seen). For missions that cost hundreds of millions of dollars to build and launch, surely we can find a small amount of money to keep them running?

To really understand why both missions are threatened, we need to delve into the budget situation at NASA, particularly with the beleaguered Planetary Science Division. It all comes down to the initial cuts to the planetary program, but not just because there is less money to work with, but because the previous decade's funding had allowed an unprecedented string of successful missions that now weighs heavily around NASA's neck.

The 2015 Budget Proposal and the Unwelcome Surprise for Opportunity and LRO

The President's 2015 budget request for NASA was released in March, kicking off the spring budget season in Congress. It acts as the starting point of congressional budget decisions. For the third year in a row, the White House proposes cuts to NASA's Planetary Science Division (responsible for all planetary missions). Additionally, the White House zeroed out the operating budgets for Opportunity and LRO in 2015, leading many people to (correctly) worry that both missions will be canceled next year.

But there's a rub: the President also released a supplemental budget request called the Opportunity, Growth, and Security Initiative (OGSI, pronounced "augsey"). This supplemental request was in response to a congressional budget deal that limited discretionary spending in 2015 to a relatively low level. The President's budget, which zeroes out Opportunity and LRO, observes this limit. But since the Administration thinks that this level of domestic spending is too low, they created the OGSI to show what they likely would have included in the budget had this limit not been imposed.

The OGSI contains $35 million to pay for continued operations for Opportunity and LRO. So these missions aren't canceled in the sense that the SOFIA telescope is canceled (appearing in neither the regular budget nor the OGSI supplemental request), but since the OGSI will never be passed into law by Congress, the two missions are not exactly safe, either.

Now, the question of how to pay for Opportunity and LRO would not normally be an issue if the Planetary Science Division's budget hadn't been cut repeatedly in the past few years, but the White House has been obsessively slashing this part of NASA for years, cutting hundreds of millions of dollars since 2013. While Congress has been able to mitigate these cuts somewhat, we still face a series of immediate and long term consequences to NASA's ability to explore the solar system, some of which we are just beginning to understand.

The Price of a Planetary Golden Age

With all of the dour budget news of late, you may not have noticed that we're living in a golden age of planetary exploration. NASA has over a dozen spacecraft exploring the solar system from Mercury to Pluto. NASA instruments are riding along on even more missions from the European Space Agency. Mars is being explored in more detail than ever before, as is Titan, Enceladus, Saturn, and the asteroid belt.

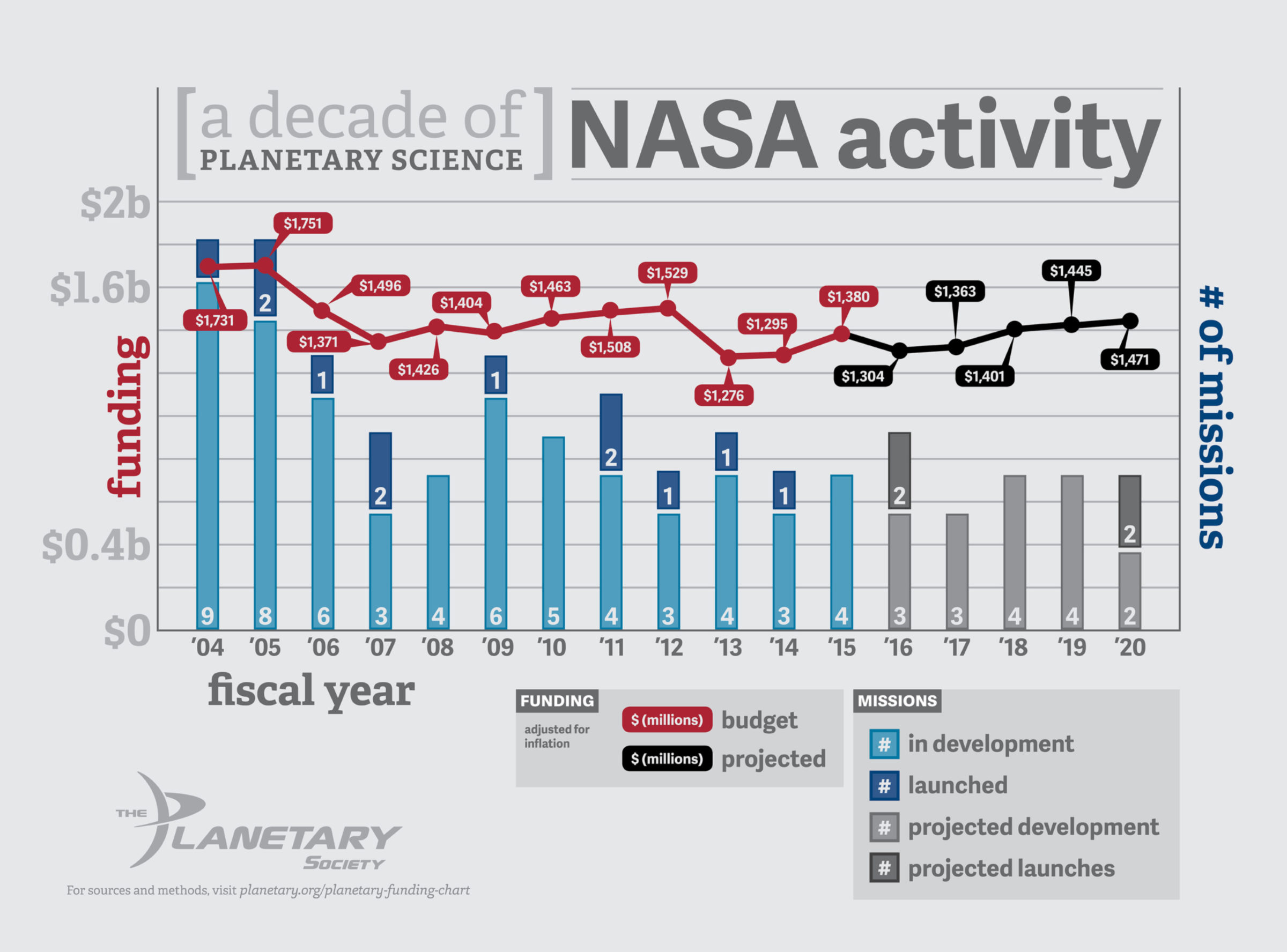

Nearly all of these missions were spawned in the previous decade (some, like Cassini, even earlier). During the ten years spanning 2003 - 2012, NASA launched twelve spacecraft to explore the solar system. It could do this because funding was healthy, averaging around $1.5 billion per year for Planetary Science. Not a single one of these missions failed to achieve their primary missions.

It's not a surprise that it takes money to operate spacecraft. You need a team of engineers, computer technicians, trajectory planners, and scientists to plan the mission's activities and keep the spacecraft safe. It costs money to use NASA's Deep Space Network—the only way to communicate with a distant spacecraft. Not all missions are equal: a relatively straightforward mission like LRO can run on about $9 million per year, but a more complicated mission, like Curiosity, costs about $60 million per year. The cumulative cost of operating a dozen spacecraft as well as NASA contributions to foreign missions (like to ESA's Mars Express) adds up to a significant fraction of the planetary exploration program. In 2013, the last year that we have full data, the cost was around $270 million—a little more than a fifth of the entire budget for NASA's Planetary Science Division.

That's a lot of money not spent on building new missions! The cost of mission operations is projected to peak at about $308 million in 2015 (assuming Opportunity and LRO continue). To put that in perspective, a small-class mission, like the upcoming Mars lander InSight, costs about $450 million to build the spacecraft.

As the decade continues, the costs of operations will decline as missions naturally come to an end.

Note that years beyond 2014 are just the Administration's proposed spending. These numbers can change.

Can the costs of operating missions be decreased? It depends. When cuts do happen, they tend to come from the scientific side of the mission, since the engineers are required to keep the spacecraft safe. But most missions have already been pared down significantly in terms of operational cost. Cassini originally needed about $80 million per year to operate, and now makes due with around $60 million, with cuts mainly hitting the science team.

The two biggest-ticket missions are Curiosity and Cassini. Spacecraft entering the prime phase of their missions, like New Frontiers, Juno, and Dawn, clock in around $20 - $25 million per year. NASA's contributions to foreign missions tend to cost in the single millions. I've created a spreadsheet of all active planetary missions and their operational costs from 2011 - 2019 which you can view at your leisure, or take a quick glance at the breakdown chart below.

So if we prioritize continued operation of existing missions (and I think we should), this becomes a fixed cost of the current planetary program. Cuts to the top-line hurt more than you would otherwise think, as there is less flexibility to absorb them. Pretty much the only thing you can do is delay, cancel, and descope new missions, which is exactly what we've seen happen.

This year, then, the White House is trying to pare down the costs of missions to open up more for future missions. NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden stated that he supports continuing missions unless they threaten the development of new missions.

The Future

The cuts by the White House don't just threaten missions now, but sacrifice the future health of NASA's planetary program. The cuts have had a particularly strong impact on future missions: this decade, we will likely see the launch of only six to seven planetary missions, a drop of about 50% compared to the previous decade's launch rate. There will be fewer replacements for the missions nearing the end of their lives. Both Cassini and Juno are planned to end in 2017, at which point there will be no NASA missions in the outer solar system for the first time in about 40 years. NASA has committed to no missions to replace them.

Even as the burden of operating existing missions decreases over the next few years, it will be difficult to replace them. The delicate balance of funding development of multiple spacecraft means that you must space out construction schedules so no spacecraft demand "peak" funding during the same year (peak funding coincides with the most active period of spacecraft construction). So even an increase to historical levels of planetary funding will necessarily require years to rebuild our fleet of scientific spacecraft. The damage has already been done.

The future is uncertain for Opportunity and LRO. Later this year, NASA will initiate its biennial senior review for all planetary science missions that have lasted beyond their primary mission goals. The senior review process evaluates the scientific potential and technical capabilities of each mission and ranks them according to this combined value. In 2012, Cassini was ranked the most highly and the now-defunct Deep Impact ranked the lowest.

Jim Green, the Director of NASA's Planetary Science Division, stated at a recent conference that if Opportunity and LRO ranked highly in the senior review, that they would continue at the expense of a lower-ranked mission. We will know the outcome of these reviews later this year.

At least one representative of Congress, Adam Schiff (D-CA), has spoken out against the cancellation of Opportunity. The Planetary Society and other scientific organizations have also come out against cancelling any missions still returning good science. We've also been asking our members and the public to write congress to show support for Opportunity and LRO (and the entire planetary program).

If Congress restores the budget for the Planetary Science program back to its historical average, funding for Opportunity, LRO, and all other operating missions becomes far easier to maintain. We could also begin other important missions, like the one to explore Jupiter's moon Europa.

NASA faces a problem of its own making: it was too successful. It built too many spacecraft that outlasted their design requirements. There is too much science to do, too many mysteries to figure out, too many questions to answer. But the obsessive desire by the White House to cut planetary exploration—an obsession now in its third year—has forced NASA to choose between its current spacecraft and the future of the program. Planetary Science has done well to preserve its most valuable assets, but we have paid an unknowable price in the loss of science return in the next ten years from the missions that may never happen.

Opportunity and LRO are the most recent and visible example of this absurd punishment of success. As most people point out, a minor adjustment to NASA's budget will ensure the continued operation of both missions. The Administration itself acknowledges the value of both missions by placing them in the OGSI. Let's not make these two unique missions pay the price of this political gamble.

>>> Make sure to write Congress to #SaveOpportunity and #FundPlanetary.

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth