Jason Davis • Nov 19, 2018

NASA's Orion spacecraft makes progress, but are the agency's lunar plans on track?

A key piece of NASA’s Orion spacecraft has arrived in Florida for processing ahead of a test flight to lunar orbit in 2020. But even as the long-delayed mission makes progress, some space industry experts question whether the agency’s plans to return humans to deep space are on the right track.

The Orion service module is a cylindrical, 4.5-meter-wide bundle of fuel tanks, power cables and engine nozzles that bolts beneath the gumdrop-shaped crew capsule that houses astronauts. The combined Orion vehicle launches atop the Space Launch System, or SLS, a massive rocket NASA has been preparing for flight since 2011.

The service module shipped from Bremen, Germany to Kennedy Space Center earlier this month. During an event Friday at the Neil Armstrong operations and checkout building, a group of NASA and European Space Agency (ESA) officials sat in front of the scaffolding-encased module and expressed relief at seeing it finally arrive in the United States.

“I was thrilled to see the service module. I kind of wanted to go up and give it a welcoming hug,” said Bill Hill, NASA’s deputy associate administrator for exploration systems development. “They wouldn’t let me do that,” he added.

ESA provided the service module as part of a barter agreement to partially pay for its share of International Space Station costs. The module is based on ESA’s ATV cargo ship, which made 5 supply runs to the International Space Station between 2008 and 2014.

Phillippe Deloo, ESA’s service module program manager, said it proved more difficult than expected to redesign ATV to work with Orion. He noted that when ESA started development on the project in 2012, the Orion crew module had already completed its early design reviews.

“We had to catch up,” he said. “It’s never good to be on the critical path. Every day, whatever you do — you do something wrong, it adds schedule.”

The Orion lunar test flight was originally supposed to happen in 2017, but delays with both the service module and SLS pushed that back to mid-2020. NASA’s Office of Inspector General says that date may slip even further. The first Orion flight with crew aboard, a lap around the Moon and back without stopping in lunar orbit, is not expected until 2023 — 51 years after humans last left low-Earth orbit during Apollo 17.

Orion and SLS have origins in the George W. Bush administration, which initiated a program called Constellation to land humans on the Moon by 2020. In 2010, the Obama administration redirected NASA to an asteroid and Mars, and under a deal struck with Congress to preserve space shuttle-era jobs and facilities, Orion and SLS evolved into their present forms. The Trump administration shifted NASA’s human spaceflight goal back to the Moon in late 2017, directing the agency to “enable human expansion across the solar system.”

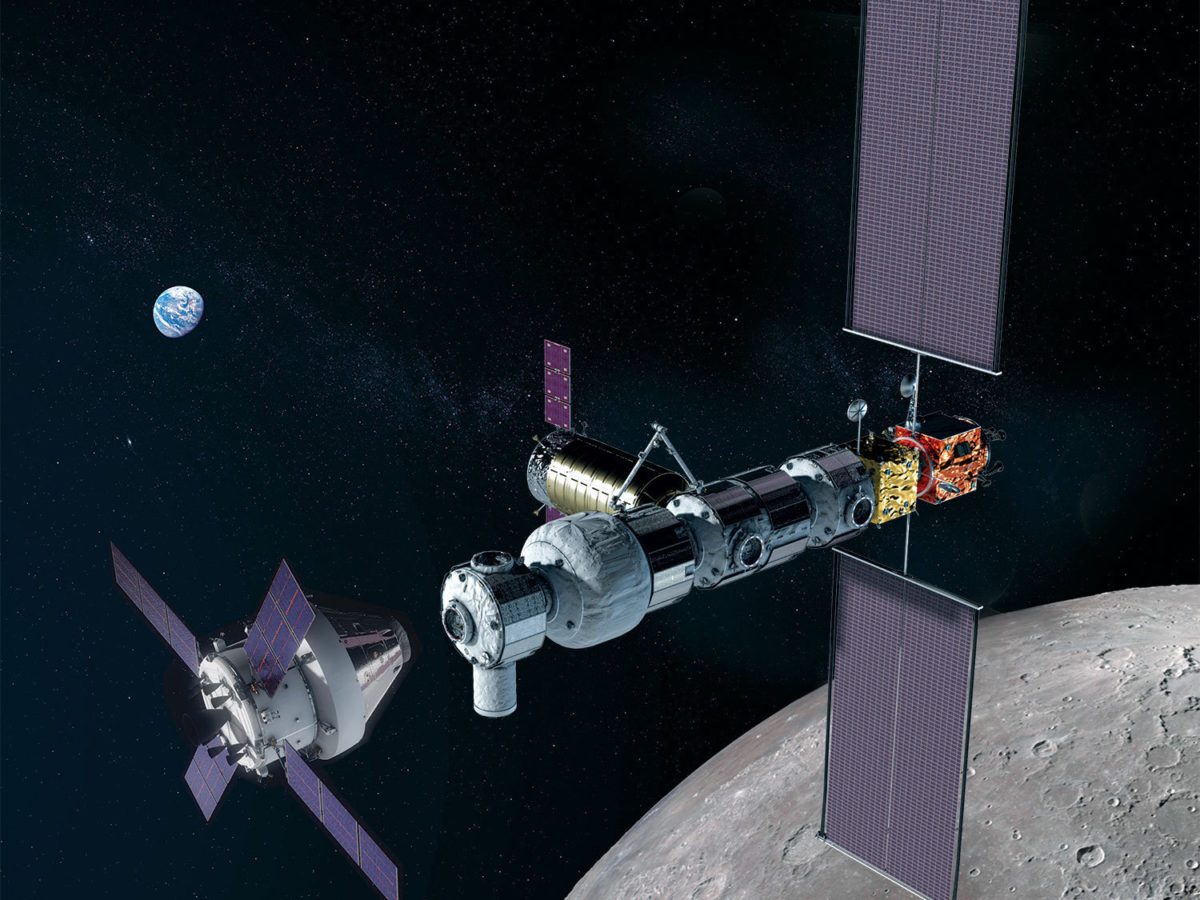

In September, NASA released a 21-page plan called the National Space Exploration Campaign to meet that directive. The plan centers around SLS, Orion, and commercial rockets constructing a small space station called the Gateway in lunar orbit that would serve as a waypoint for missions to and from the lunar surface. As for surface missions, rather than going straight to large, Apollo-style landers, NASA plans to start with small robotic missions and scale up from there.

The plan also says American astronauts will be back on the Moon by 2030, and more recent statements by NASA officials have pledged an earlier goal: 2028. Mary Lynne Dittmar, the president and CEO of the Coalition for Deep Space Exploration, which represents the aerospace industry, supports the strategy.

“The current approach, which involves a broad based coalition of industry, international partners and government, can establish U.S. leadership in space for decades to come, unleashing the best of innovation, entrepreneurial spirit, government-funded infrastructure, and expanding international relationship and U.S. soft power – all while also supporting the aerospace and defense sector at home,” she said.

But many experts say a Moon landing by 2028 is impossible without a major funding boost to NASA’s human spaceflight program. Approximately half of the agency’s $21 billion current annual budget directly or indirectly supports human spaceflight activities. Most of that is consumed by International Space Station operations and transportation, SLS, and Orion, leaving little wiggle room to build hardware in support of a return to the Moon.

“Extraordinary plans require extraordinary budgets, which NASA has not seen since the Apollo missions,” said Laura Seward Forczyk, founder of Atlanta-based space consulting firm Astralytical. “NASA has been locked in a cycle of different but similar Moon-to-Mars or asteroid-to-Mars or LEO-to-Mars human spaceflight architectures for decades.”

To shift more funds to deep space exploration, the Trump administration has proposed to stop directly funding the ISS in 2025 and turn the space laboratory’s operations over to the commercial sector. The National Space Exploration Campaign claims that once commercial astronaut providers like SpaceX and Boeing are up and running, a new market will flourish for in-space activities that include tourism and manufacturing.

Matthew Hersch, a science and technology historian and assistant professor at Harvard University, says that premise is flawed.

“It imagines a new program of exploration to be paid for by convincing private industry to pay for NASA’s existing human spaceflight operations, though it describes no mechanism for creating such a market,” he said.

Congress has already signaled it is unlikely to support a withdrawal of ISS funding in 2025. Dittmar notes establishing the infrastructure, suppliers and investment pipelines to support commercial activities currently happening on the International Space Station took years to develop.

“Personally I think [repeating the model for a standalone commercial market] will happen, but I don’t think it will happen by 2025,” she said. “The focus of both government and private efforts needs to be on establishing demand, which is the crimp in the economic development pipeline."

With the fate of the ISS up in the air and no funding increase on the horizon — on the contrary, the Trump administration is considering a 5 percent cut to agencies like NASA — critics say the agency should rethink its deep space exploration plans, starting with the Gateway.

Hersch, the Harvard space historian, called it a “useless money sink.” Former astronauts Terry Virts and Buzz Aldrin have voiced opposition, with Virts saying the Gateway will divert time and money away from landing on the lunar surface. Michael Griffin, who served as NASA administrator during the George W. Bush administration and oversaw the origins of Orion, called the Gateway a “stupid architecture.”

Current NASA budgets envision $2.7 billion being spent on the Gateway from 2019 through 2023. The first piece of the outpost, a power and propulsion element, would launch on an uncrewed commercial rocket in 2022. Two more Gateway pieces could arrive with an Orion flight as soon as 2024.

Another money-saving option could be re-thinking the costly SLS program, and NASA’s new plans seem to open the door on that option.

“Overall, the National Space Exploration Campaign is different from past endeavors that were unsustainable or never matured,” the report says, citing commercial partners as a reason: “It is in the national interest to have reliable, lower-cost launch capabilities and the National Space Exploration Campaign will take advantage of those capabilities as they emerge.”

Dittmar disagrees that this implies SLS will be replaced. She said SLS can focus on deploying large infrastructure pieces, paving the way for more cost-effective launchers to tackle transportation and refueling jobs.

“This is not an ‘either or’ equation,” she said. “There is entirely too much focus on launch vehicles – they are a means to an end, but not the end itself."

Forczyk predicts a pivot toward commercial heavy lift vehicles will only take place if two or more alternatives fly, and NASA is able to replace funding losses in Congressional districts that support the SLS program.

“Powerful members of Congress will not give up jobs and funding coming into their regions without being able to announce a new government initiative to take its place,” she said.

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth