Craig Hardgrove • Feb 12, 2014

What is NASA for?

Why are you interested in space? And I don’t just mean space I mean stars, planets, the solar system...whatever is “out there”. I know you’re interested in it because everyone is. We all have our different reasons, but honestly, who cares what they actually are? The fact that almost everyone is interested in space is, in itself, interesting. You can’t say the same for many, if not most, other topics out there. If I asked the following questions: “Why are you interested in pandas?” or “Why are you interested in interior decorating?” Would the same numbers of people be interested in those things? Doubtful. Oh sure, those topics can be interesting but most people will probably need a bit of persuasion or some additional information first. And what’s amazing is that for space, none of that is required. I can ask why you are interested in space without needing to convey any other details because I already know that you’re interested. There’s no convincing necessary. So what’s a more interesting question? Maybe, “Why is it that so many people are interested in space?” The answer to that involves an entirely different question...but I’ll get back to that later.

In Search Of A Vision

When I read or hear people bash NASA for their lack of vision, or much worse, demand that the agency justify its very existence, I’ll be honest with you, there is a part of me that agrees with them. Every large government agency should make it clear to the people it serves what it does for them, and for those that speak or write publicly it may be the case that this message either didn’t get through, or that it wasn’t communicated at all. And what about a vision for the future? Well, the part of me that agrees says, yes, why doesn’t NASA set out on a grand vision of, oh I dunno, sending humans back to the Moon, then to a near-Earth asteroid, all in preparation for an eventual long-duration stay on Mars...wow that sounds great...wait, wait, they should draw up a 10–20 year vision that includes a roadmap to get humans exploring the solar system again! Wai-- What? … Really? Well, apparently it turns out that is NASA’s plan (see NASA’s contribution to the Global Exploration Roadmap report, published in 2013) but I’m guessing no one knows about that. In any case, the reality is that NASA’s grand vision isn’t up to NASA at all. It’s up to Washington D.C. and, specifically, those that set NASA’s budget. In the 1960s the United States Chief of the Executive Branch stated we were going to put humans on the Moon and, lo and behold, it happened. It happened because it was made a national priority, but that wasn’t the only reason. NASA got a “whopping” 5% of the federal budget during portions of the Apollo program (and, for reference, has been getting around 0.5% or less for the past 5-10 years). And so we went to the Moon, and it was tremendous, but quite suddenly...we stopped going. Regardless of why we stuck it out and landed humans on the Moon, it actually may be more interesting to consider why we stopped.

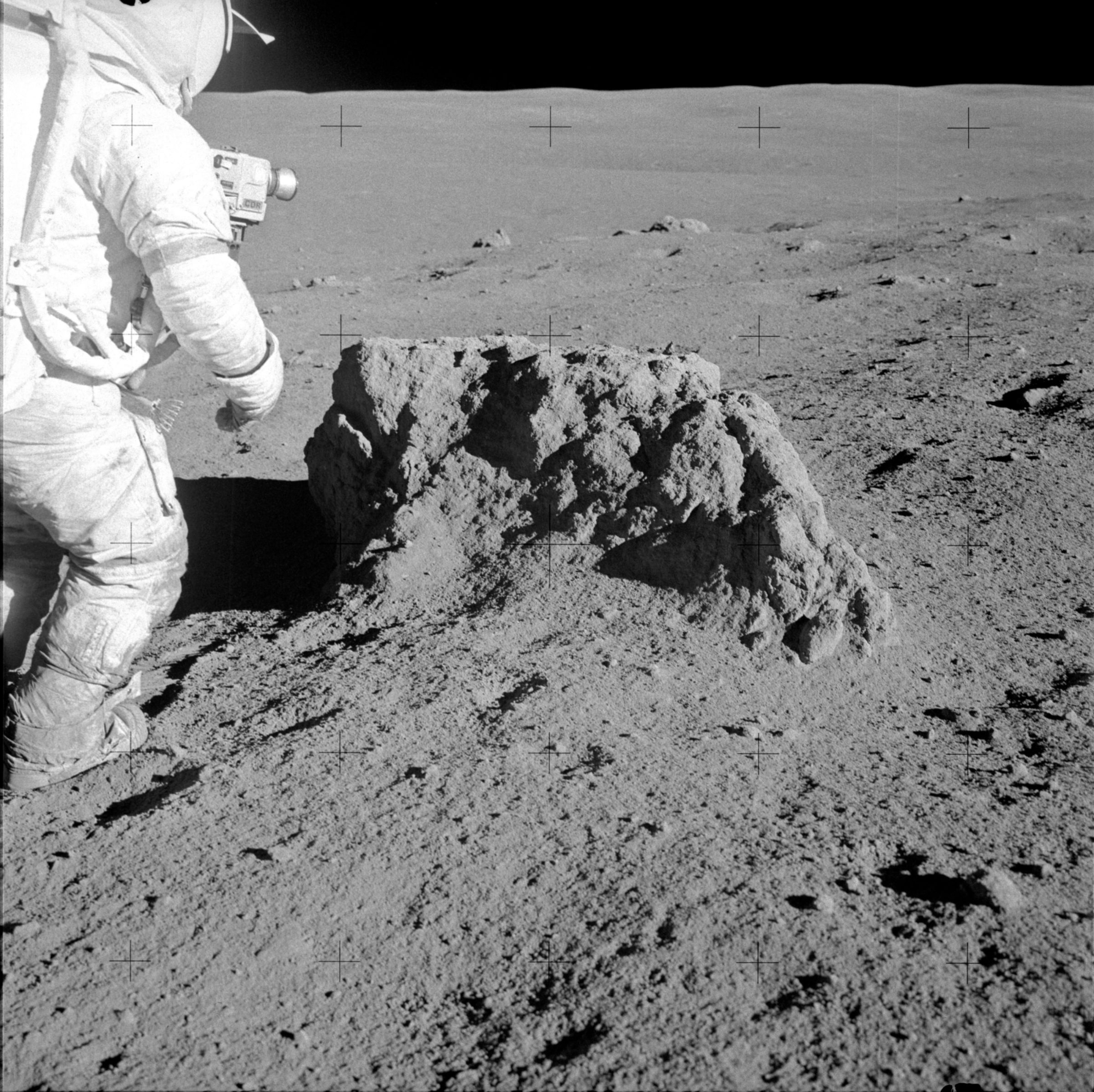

From the 1950s to the early 1970s we entered the Space Age—we went from literally zero Earth-orbiting satellites to hundreds. We became experts at building rockets, launching them successfully, building satellites, communicating with them, processing and understanding their data. In those early days we saw NASA and other government agencies using this new technology to launch and operate satellites in orbit. Eventually, by the late 1960s, even a few private institutions got in on the fun. And by the early 1970’s NASA was getting to a point where they could send humans to the Moon with some regularity. If we could have sent the NASA Administrator to the Moon at that time, he would have looked around at the lunar landscape, dotted with rovers, landers, and geophysical monitoring stations, and been amazed at what his agency and his government had done. But if he then looked back at the Earth through a telescope, he would have only seen a handful of commercial satellites in orbit, a satellite industry that still needed government help getting off the ground, and (if such things could be seen) no clear path towards a thriving industry in space. The vision of humanity’s future in space needed help. There was no clear path towards non-governmental funding of space exploration that would eventually allow private industry to follow NASA’s footsteps to the Moon, at least not soon. And this really gets to the meat of the issue. NASA stopped going to the Moon for a lot of specific reasons, but one of those is that it got a little ahead of itself. So let’s go back to the 1800s...

In Search Of An Analogy

The US government has been in the business of funding “missions of exploration” to seed future growth before. Famously, Lewis and Clark were chartered to explore the American West to look for, among other things, railway passages. The idea was to make maps, to find suitable land to settle, and to find routes to get there so railroads could be used to ferry people, goods and services, which would eventually spur new businesses (or even whole new industries) out in what was then uncharted territory. The railroads themselves were to be owned and operated by private corporations, all of which were poised to make a hefty profit. But the point of government involvement was primarily to do the exploring, to do the risky up-front work that needed to be done to pave the way for a profitable, and successful, industry. But to say this is the best analogy would be misleading. As soon as Lewis and Clark saw a tree, and surely they saw many, it was possible to see dollar signs. The same is true for rivers, arable land, buffalo, mountains, caves...as humans we know how to turn these things into dollars. It’s easy to see resources like these on Earth and figure out how to make a living harvesting their value and selling it to other humans. Actually making money off of it, however, if the hard part and even on Earth that's not always easy. In that sense, this analogy falls apart because as soon as Lewis and Clark found those things, and they did in abundance, it was clear that money could be made, railroads could be built, industries established, onward and upward. But when we look upward at, say, the Moon or an asteroid, there isn’t much in our human brain that screams... goldmine! In fact, it’s taken planetary science, the Apollo program, and the study of meteorites to really tell us what we’re looking at. And it turns out from all that science, as far as resources go the answer is a little fuzzy... the most promising commodities seem to be hydrogen and platinum-group-elements (PGEs), but if you were to grab a rock from a random asteroid’s surface it’s not clear how much hydrogen or PGE you’d collect. That’s not to say a goldmine doesn’t exist in the asteroid belt, assuredly it does, but we’re going to have to find it first, nugget by nugget. On the Moon, there’s a wealth of data telling us hydrogen is there, in larger abundances in permanently shadowed craters and, in albeit smaller quantities, bound up within the lunar soil itself. So maybe the proper analogy actually the US government’s funding of the nascent commercial airline industry early in the 20th century. We knew how to fly, but the details of where to go and what to do needed some development. Maybe there just isn’t a perfect analogy, but that’s OK, we’re breaking new ground.

In Search of New Frontiers

The science tells us we have to be smart about where we go looking for resources. And laying the groundwork for this approach is at least one company, Planetary Resources, who intends to search the skies for mineable asteroids using a series of telescopes launched into low-Earth orbit. Is this, however, the job of a corporation? Experience tells us that, at least when a market is pre-defined the answer is yes, insofar as oil prospecting is the job of the oil industry. And surely we can imagine a future where “Space Lewis and Clark” found a plantinum group element (PGE)-rich goldmine asteroid and Planetary Resources has set up shop there. And in such a world it’s easy to imagine Planetary Resources taking short hops, skips and jumps to prospect around for nearby treasure troves, but that’s not yet the world we live in. We live in a world where the market for PGEs is fairly well established, but where taking a scoop of a sample on another world and analyzing its composition is so exceedingly rare (we’ve done this for only 6 planetary bodies, using a variety of different techniques—none of which are particularly sensitive to PGEs) that there are a few technological steps required before it would be reasonable to start a business based on it. It will certainly be possible eventually, but it’s going to take time. So they’re planning to explore... doing what has traditionally been NASA’s job, hoping that they can seed an industry. That is new ground for which there may be no analogy. Planetary Resources is also a bit of an outlier, not only in what they plan to do, but in terms of funding. They plan to explore using a telescope, the ARKYD, whose development they are amazingly trying to crowd-fund using (at least in part) Kickstarter. Again, this is new ground. Ground where dreams of funding success can be made possible using new crowdsourcing methods like Kickstarter, but by and large, the funding of the railroads—I mean, the rockets—is coming from an evolving version of NASA. The big players, like SpaceX and Orbital, are primarily funded by NASA’s Commercial Cargo and Crew Program which accounts for more than half of NASA’s FY2014 commercial spaceflight and space technology budgets. Much of NASA’s remaining commercial space budget is for small satellite launches and technology development to ensure that the infrastructure is in place to build a profitable industry, so that all the players and potential players can reliably create space hardware and have the services they need to make it work. And while NASA is doing all that they’re still landing cars on Mars (Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, Mars-2020), sending satellites to Jupiter (Juno arrives in 2016) and Pluto (New Horizons arrives in 2015), flying around the rings of Saturn (Cassini), and darting around the asteroid belt (Dawn is flying from Vesta to Ceres this year).

In Search Of It All

So NASA does have a vision, they’re clearing the weeds in interplanetary space and making sure that private industry has everything they need for low-Earth orbit. NASA came back from the Moon and decided we needed some help getting there on our own. Sure, it’s taken longer than we would have liked, and it’s not as sexy as putting a human on Mars by the end of the decade, but sit back, have a drink or two and start imagining the future...you just might end up swooning. Virgin Galactic is set to fly their maiden flight this year where passengers get to experience about 6 minutes of weightlessness and see the whole of the Earth out their space-plane window. It will be televised internationally. They have also developed a lesser-known space vehicle, called LauncherOne, which will soon be available for deploying satellites and experiments into low-Earth orbit. SpaceX, as I’m sure you already know, has had many successes and is quickly emerging as a leader in providing reliable, low cost launch systems to Earth orbit. There are other players in this space as well, and some are seeded by private investment, some by NASA. The landscape is rapidly changing, and we’re seeing the beginnings of a real industry. Smaller companies are sprouting up to fill the needs of the bigger players, and still others are working on longer-term industry goals by creating large-scale service satellites, robotic landers, telescopes, and other exploration vehicles for prospecting.

NASA’s goals as they relate to the commercialization of space are clear: To explore and pave the way for industry and for people. And you don’t even have to take my word for it. Read it for yourself in The National Aeronautics and Space Act, 51 USC

§ 20112(a)(4), and the National Space Policy (Dec. 18th, 2010), which mandates that NASA work with the industry to advance the commercial space sector:

National Aeronautics and Space Act

“Commercial Use of Space -- Congress declares that the general welfare of the United States requires that the Administration seek and encourage, to the maximum extent possible, the fullest commercial use of space.”

National Space Policy

“A robust and competitive commercial space sector is vital to continued progress in space. The United States is committed to encouraging and facilitating the growth of a U.S. commercial space sector that supports U.S. needs, is globally competitive, and advances U.S. leadership in the generation of new markets and innovation-driven entrepreneurship”

Why All This Searching?

So let’s get back to the original question: Why are you interested in space? I asserted that regardless of your answer you would assuredly be interested in it, and that was because you were answering a different question entirely.

There is a simple, unifying thing that makes us all say we are interested in space ... and that’s because the question really is, “Why are you interested in the unknown?”

The answer is easy. It’s because you are human.

The role of NASA is to help us understand the unknown, and I would argue that helping to establish a commercial space industry, an industry that is making space a familiar part of our everyday world, is doing just that. We are witnessing the birth of a new space industry that will ferry human space-farers into low-Earth orbit and eventually beyond. Slap yourself, this isn’t a dream. You are actually living at the dawn of a new Space Age…maybe call it the NewSpace Age? We shouldn’t forget that NASA played an important part in bringing it about. And while NASA is busy sowing those seeds, it continues to do the job it has always done…peering around the corners, charting paths, and exploring the unknown parts of our solar system. In the next few years we will get to see parts of Mars, Jupiter, and even Pluto (we still love you Pluto) that we’ve never seen before.

We are exploring these worlds because we don’t know what’s there.

Every picture tells us something new and honestly, it doesn’t really matter what part of the electromagnetic spectrum, oscillations of magnetic fields, or specific organic molecules we analyze. We’re going to learn something new, and we’re going to see something that we’ve never seen before. Is there money to be made in that? Sure, maybe. But until then, NASA and all of their international space agency partners are the only ones doing it.

So what is NASA for? It’s for answering those questions about our solar system and our universe that we don’t yet know the answers to. And it’s also for funding technologies, mission concepts, and other enabling systems that will, eventually, allow robots and humans to venture out into the solar system without NASA’s help at all. They’re blazing a path to the outer reaches of our solar system, exploring in detail our nearest neighbors like Mars and the asteroid belt, and telling us what to expect when we get there.

And don’t you want to know what’s out there?

I already know that you do, because you’re human.

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth