Casey Dreier • Feb 05, 2014

Cosmos with Cosmos Episode 12: Encyclopedia Galactica

Cosmos with Cosmos was a weekly series that encouraged Society members to re-watch Cosmos with a shared group, a cosmo(politan), or other drink of their choice. The Planetary Society published weekly episode discussion pieces to complement the original series before the Neil deGrasse Tyson-led 2nd season in 2014. You can currently watch the original Cosmos streaming on twitch.

« Episode 11: The Persistence of Memory | Episode 13: Who Speaks for Earth? » |

Note: It seems that Cosmos has been removed from every online streaming service and iTunes over the past month. This is likely in preparation of the new series, but unfortunately that means there is no legal means to watch the original besides the original DVD box set.

Few pursuits in history elicit such a conflicting mix of high-minded ideals and self-destructive delusion as does the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Its serious philosophical implications are commonly overshadowed by the tawdry, breathless declaration of the crackpot. And much to our collective sorrow, the crackpot has won.

In episode 12 of Cosmos, Carl Sagan strives to legitimize the search for extraterrestrial life. He largely succeeds, and in doing so returns the series to its fine form. Despite one misstep which I will discuss later, "Encyclopedia Galactica" is a hugely improved hour of television from the series's nadir in the previous few episodes. It is a nicely-structured episode that plays to its strengths: Sagan directly dismantling the myths about UFOs; a clear, compelling story of humans cracking the hieroglyphic code, providing a nice metaphor for the larger ideas of the show; stimulating speculation about extant life; and a general sense of an expanded worldview and hope for the future that stays with us for days after a viewing. I thoroughly enjoyed this episode.

I want to address what I consider to be the big misstep of the episode: the reenactment of Betty and Barney Hill's "abduction." While Sagan goes to great lengths to debunk this story, visuals are far more potent than words, particularly on television, and I suspect that most people watching this will remember the abduction sequence more clearly than Sagan's careful explanation of how it wasn't true. For those people who are unsure if UFOs are real, or even exhibit a slight proclivity towards wanting them to be true, the stronger memory may serve to push them towards the wrong conclusions. If Sagan had asked me (and unfortunately I had not been born at the time), I would have recommended that he reverse the presentation: describe the Hill abduction and then visually illustrate the skeptical response on the story.

But despite the lack of visual flair, Sagan slices through the story with a logical precision that would be chilling if it weren't so satisfying. I'm guessing that these simple sit-down sessions with our host will not transition into the new Cosmos series; CG has become too cheap and too expected. But these sessions of Sagan sitting down and walking us through an argument (which is repeated later in the episode regarding the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs) are intimate and disarming, evocative of sitting with a respected professor in the quad on a sunny day. For all of the new knowledge that we are presented with throughout Cosmos, these are brief moments of stability, where Sagan walks us through arguments with a cheerful confidence and simple illustrations.

Humanity seems to have a deep desire to assign unexplained experiences to the prevailing cultural superstition. Demonic possessions, ghosts, and witches each had their times of peak activity, each one dying out to be replaced by something new. Sagan explores this in his great book on reason, "The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark." Aliens, at the time, were becoming the big new cultural superstition, representative of our rapid technological development and increasing awareness of the size of the cosmos. Cosmos was filmed just a few years after Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," which propelled the concept into pop-culture and generated a brisk trade of conspiracy theories. I think this is why Sagan felt compelled to address this so strongly in this episode, particularly as real SETI searches were beginning around that time. SETI always suffered from a connection to the unsavory elements of the UFO movement, and for government funding to be consistent and available, the separation between the two was necessary.

I think he had some effect. Look at the plot below, which tracks the occurrence of the word "UFO" in books over time (from Google's N-gram viewer) which is a rough approximation of popularity:

You see a peak in 1980, followed by a brief decline and the growth that peaks in the late 1990s, which I ascribe to the popularity of the TV show "The X-Files" and the televised "Alien Autopsy" hoax. Probably not coincidentally in 1993, when The X-Files debuted and when cultural interest in conspiracy-minded UFO theories began to grow again, Congress politicized NASA's funding for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) during a budget squeeze and cancelled all funding for the program. Despite the enormous interest from the public, the topic had become so mired in crackpottery that Congress treated it with derision, and the serious, scientific, and rigorous search for extraterrestrial intelligence never happened. SETI has continued on a small scale thanks to The Planetary Society and the SETI Institute, but never on a level equal to what could have been with NASA's program.

We all lost when SETI funding was cancelled, but it must have been particularly hard for Sagan. His voice betrays his schoolboy excitement as he narrates about what a joy it would be to discover messages from an alien civilization. Even during the sequence with Champollion, you can hear his delight in the challenge of deciphering an unknown message.

The sequence with Champollion suffers from the usual Cosmos pacing issues (budget-related, I assume) and is chock full of our usual close-up shots of actors looking at things. But the sequence works, educating much of its viewing audience that the hieroglyphs were a mystery for over a thousand years, that only through careful observation and logical thought was someone able to deduce their meaning, and through this we are the recipients of a one-way conversation with with civilization. It also provides a crucial historical precedent for the search to understand messages from societies alien to us. Radio SETI would not be the first time humans yearned to understand a message from another civilization, assuming a message could be found.

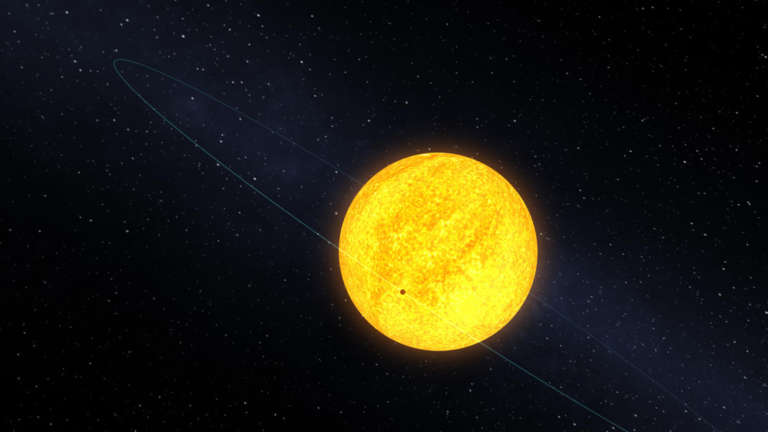

After the historical, Sagan turns to the scientific, describing humanity's newfound abilities with radio telescopes and the theoretical framework for extraterrestrial intelligence set by the Drake equation. He walks us through two possible scenarios for the Drake equation, one extremely optimistic and one more pessimistic. Both of the numbers he gives are probably wrong, but it was never meant to be an accurate equation, it was there mainly to define boundaries. This equation has persisted, and is more relevant today than ever before in light of NASA's Kepler spacecraft, which has discovered thousands of exoplanet candidates. There is also the rise of the Rare Earth hypothesis, which asserts that while microbial life may be somewhat common, complex, intelligent life may be extremely rare. There may be no one to talk to for tens of millions of light years.

But Sagan was an optimist, and we end the episode with a moving sequence featuring his dreamed "Encyclopedia Galactica," where we see highlights of a vast collection of worlds, some inhabited, some similar to us, some far different. We get science-fiction level speculation (though grounded from very scientifically-literate sources) about great works of engineering, about advanced species surviving for millions of years, of close relationships between civilizations that pursue great adventures. I have to admit: I love this sequence—it's stirring, hopeful, and thought-provoking. It perfectly encapsulates the "personal voyage" part of the subtitle. This is Sagan's show, and he's not afraid to share his dreams about what could be—what he wants to be—out there. Few series are daring enough to indulge in the speculation that all of us are prone to. By doing so, Sagan touches us in a way not usually associated with scientific programming, and he acknowledges a deeply human desire to be a part of something far grander than we.

Stray Observations

I don't have a lot to say on this topic, but I just wanted to mention that I like the idea of science and mathematics serving as a Rosetta stone for deciphering messages from other worlds. It's a great analogy.

The Drake equation remains a hotly-debated subject to this day, with the rise of the Rare Earth hypothesis seriously challenging the number of intelligent civilizations. We also know several factors of the equation far better than we did in 1979, particularly the rate of star formation, the number of stars in the Milky Way, and the number of stars that have planets (which I think is about 100%). The number of habitable planets per planetary system may be partially answered in the next few decades.

Before astronomy truly matured as a science, it wasn't uncommon to assume that life existed elsewhere in our solar system. Both Kepler and Galileo thought that there was life on the Moon. The "discovery" of the canals on Mars were attributed to massive engineering works by martians. Venus was assumed a swampy jungle. I think that it wasn't until astronomers truly grasped the utter hostility of space that extraterrestrial life became increasingly unlikely and precious.

The whole sequence with Champollion could have been inserted into the previous episode (though I'm glad it wasn't, since I didn't like the previous episode). But the message about the persistence of the memory of Egyptian culture into the future would have resonated with the show's main theme. Also a nice thought: we have an interstellar equivalent of Pharaonic inscriptions: Voyager's golden record.

"Encyclopedia Galactica," is now a pretty dated reference. Maybe they'll modernize it to "Galactipedia" in the new Cosmos?

If you're watching the DVDs, the Cosmos Update highlights The Planetary Society's META project, our privately funded radio astronomy SETI with Harvard's Paul Horowitz. It ran through the 1990s before the telescope failed. We continued the search with Horowitz but in the optical spectrum with our OSETI project.

Quotes

"If we can't identify a light, that doesn't make it a spaceship."

"With 400 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy alone, could ours be the only one with an inhabited planet? How much more likely it is that our galaxy is throbbing and humming with advanced societies. Perhaps near one of those pinpoints of light in our night sky, someone quite different from us is glancing idly at the star we call the Sun and entertaining—just for a moment—an outrageous speculation."

« Episode 11: The Persistence of Memory | Episode 13: Who Speaks for Earth? » |

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth