Jason Davis • Nov 23, 2015

Surveyor Digitization Project Hints at Long-Lost Lunar Treasures

A project to digitize more than 90,000 images taken by NASA’s five Surveyor spacecraft in the 1960s has revealed early hints of never-before-seen treasures captured by America’s first robotic lunar landers.

Scientists at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory started scanning the original Surveyor film reels in March, and finished up last week. The Surveyors were NASA's first probes to soft-land on the moon, and as little as 2 percent of their images have ever been seen. A set of the program's original film reels has been stored at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory for decades.

The project team is now starting the arduous task of formatting the images for submission to NASA’s Planetary Data System, the agency's master archive of space imagery. After that, anyone will be able to browse and download the pictures for free.

The team hasn’t had much time to play with the images they've scanned during the eight-month process—the emphasis thus far has been the tedious task of digitizing the data. Scanning took place inside a clean room built at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. The fifty-year-old film reels are in good shape, but Shane Byrne, the project's principal investigator, wanted to get the pictures scanned as soon as possible.

"At a fundamental level, this is like a rescue operation," Byrne said. "The most important thing is to get the frames digital and freeze them so they don’t decay any more."

Last week, John Anderson, a media technician working on the project, loaded the final reel of film onto an automated scanning machine on loan from Austin, Texas-based Stokes Imaging. The reel contained a series of calibration images taken at Cape Canaveral before one of the Surveyor probes launched.

"It’s been in the can awhile," Anderson said, during a team meeting. "The film is curled as you take it off the roll." In the clean room, I watched him mount the reel onto a spindle, unroll the film between two pieces of glass, and attach it to an empty reel. A bright light was positioned under the two pieces of glass, and an overhead camera snapped an image of each backlit photo as the film gently spooled through, stopping one frame at a time. Anderson observed the process carefully, occasionally fine-tuning each frame before the shutter clicked.

It was a tedious process. The bulk of the scanning was done by Anderson, LPL's Maria Schuchardt, and a graduate student that pitched in earlier during the project. The team originally estimated there were 87,000 images, but they acquired more reels from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, bringing the total up to about 93,700. Of those images, Anderson estimates 92,000 are usable, valid pictures from the lunar surface.

I asked Anderson for the size of the raw image cache. Sitting behind a dual-screen Apple computer in LPL's Space Imagery Center, he selected the project folders and tried to open a properties window to get the number. We waited for several minutes as the computer's hard drives grinded away, struggling to come up with an estimate. We finally gave up. (Anderson estimates the figure is about 5 terabytes.)

Though the team has mostly been busy scanning, Anderson has found a few minutes here and there to play with the raw data. He created an algorithm to normalize the brightness levels across a set of frames, and has been able to stitch together part of a mosaic from Surveyor 5 that contains 70 images thus far. Because the raw files are so big, he had to make intermediate mosaics first, and then stitch those together. Here’s an early draft:

Anderson also created a composite high dynamic range Earthrise using 11 frames captured by Surveyor 7. This technique—overlaying multiple pictures of the same thing—is often used by amateur astronomers to make pretty pictures.

I asked Anderson if we could randomly browse through the archive and look for something interesting. We found a series of images showing Surveyor 7 scooping the lunar surface, and I put those together into an animated GIF:

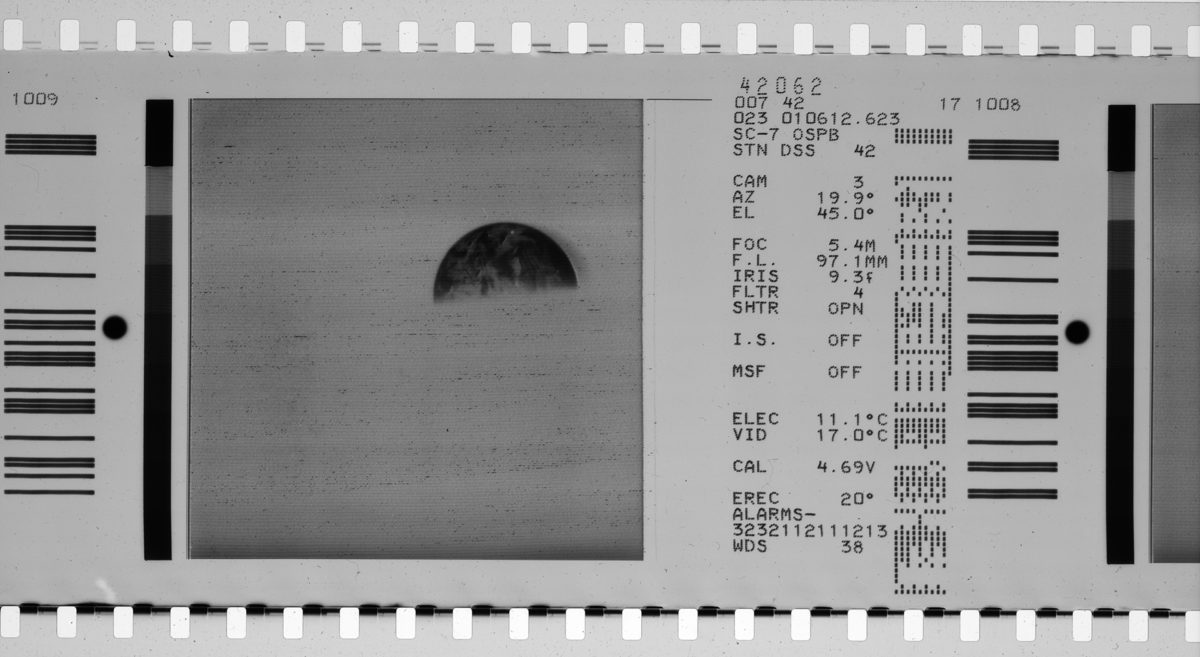

To submit the raw Surveyor images to the Planetary Data System, Byrne’s team needs to convert the metadata stamped on each frame into a format that the PDS can accept. That metadata comes in three formats: human-readable text, binary coded decimal (BCD), and a barcode.

The team first focused on the text, hoping they could automate the digital conversion process through optical character recognition—OCR. But a closer look shows that the text is printed in a dot matrix—each number and letter is actually a series of small dots. That tends to confuse OCR readers. One possible workaround is applying a blur to the text block to connect the dots.

Another option is creating a process to read the BCD or barcode block. But the details on how to decode these blocks have been lost over time. Justin Rennilson, a project member who was also on the spacecraft's original camera team, has been working on interpreting the BCD blocks. He discovered the format of the blocks changed over the course of the Surveyor program.

Now that the scanning portion of the project is over, the team is turning its full attention to the metadata puzzle. The process they end up using to parse the 92,000-plus images needs to be nearly 100 percent accurate.

Back in the Space Imagery Center, Rennilson looked over a large printout of Anderson's early mosaic. I asked which part of the image was in the foreground, closer to the camera.

"Look for the fine fragments," he said. "If you can’t resolve them, it’s far away." Surveyor scientists used this trick to help train astronauts how to judge distances on the lunar surface.

"That was a tool we told the astronauts to use on the moon," Rennilson said. "And it worked for most of the astronauts." One exception, he said, was Alan Shepard. America's first human in space apparently never quite got the hang of it.

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth